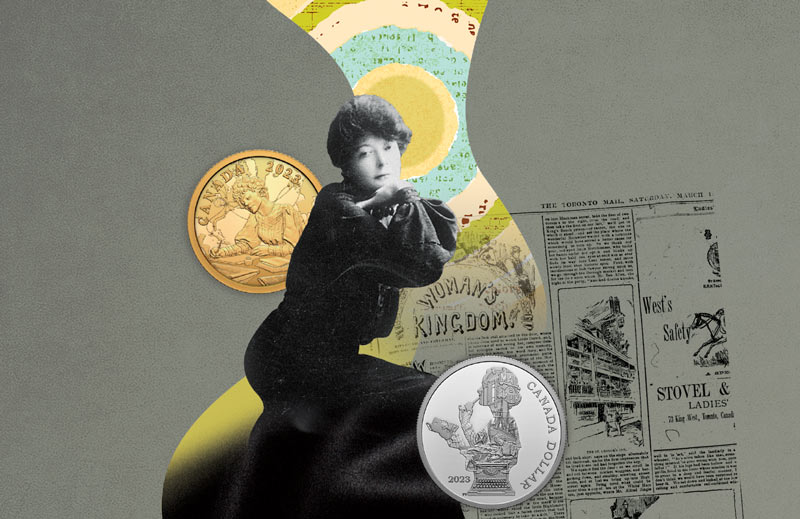

A portrait of journalist Kathleen (Kit) Coleman surrounded by news clippings from the 1898 Spanish-American War and commemorative coins marking 125 years since Coleman became the first accredited female war correspondent in North America.[The Carbon Studio/LAC/PA-164916; Royal Canadian Mint (2); Library of Congress; The Toronto Mail]

During her lifetime, journalist Kathleen (Kit) Coleman achieved many firsts—and she’s still doing so more than 100 years after her death.

In February 2023, the Royal Canadian Mint issued two collector coins in her honour, marking 125 years since she became North America’s—and possibly the world’s—first accredited woman war correspondent. Coleman also became the first female journalist to appear on a Canadian coin.

During her lifetime, her many other accomplishments included: the first woman journalist to write and edit a column in a Canadian newspaper, in 1889; one of 16 founders of the Canadian Women’s Press Club (now the Media Club of Canada) and its first president, in 1904; Canada’s first female syndicated columnist, in 1911.

Still, Coleman is perhaps best known for her coverage of the Spanish-American War in 1898 for Toronto’s Mail and Empire. At the time, she had also become one of the best-known columnists in Canada. As a publicity brochure produced by the newspaper noted in 1896, Coleman’s column was “acknowledged to be unexcelled on this continent.”

Kathleen Coleman was born Catherine Ferguson in 1856 at Castleblakeney in Ireland’s County Galway. At 20 she entered an arranged marriage to a wealthy Irishman named Thomas Willis, 40 years her senior. Left penniless when disinherited by Willis’s family four years after his death, she worked briefly as a tutor and spent some time in France.

In 1884, she immigrated to Toronto, where she self-identified as a childless young widow who needed to make a living. She reinvented herself, changing her name from Catherine to Kathleen and slicing eight years off her age. She worked as a secretary to support herself until marrying her boss, Edward J. Watkins. They moved to Winnipeg where their two children, Thady and Patricia, were born.

But it was an unhappy marriage as Watkins may have been, among other unpleasant things, a bigamist. When that marriage ended, Coleman dropped the surname Watkins and returned to Toronto with her two young children. At first she did odd jobs to earn a living, but she also wrote articles for local magazines, mainly Saturday Night.

Coleman was hired by The Toronto Daily Mail newspaper in 1889 to write a column for the women’s pages. At first it was a short entry called “Fashion Notes and Fancies for the Fair Sex.” At the time, female journalists were typically limited to writing about recipes and fashion. And while Coleman did launch the first “lovelorn” column, she also wrote on a range of other matters including politics, business, religion and science.

Coleman penned colourful accounts of her journeys to Ireland, England, the West Indies and across North America, sometimes going undercover in other cities to write about social issues and the plight of the poor. Her column soon grew longer, filling seven pages. Called “Woman’s Kingdom,” it was eagerly read by both men and women, including Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier.

Coleman is perhaps best known for her war correspondent feat, when she covered the Spanish-American War in 1898 for Toronto’s Mail and Empire.

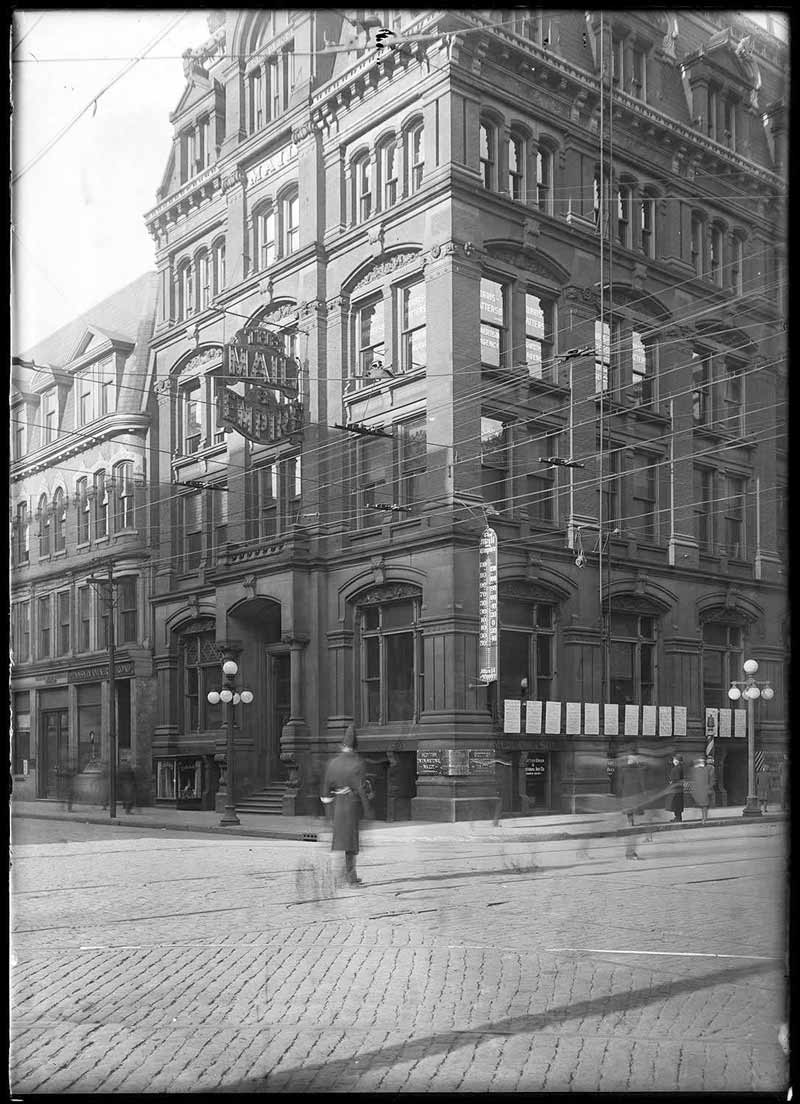

Coleman was renowned for her work in Toronto’s The Mail and Empire newspaper.[City of Toronto Archives]

Readers were curious about who Coleman was, but she preferred to keep her personal life private. Most of the time, she left readers guessing about whether her column was written by a woman or, as some wondered, by a man pretending to be one.

Coleman was “an avid reporter and eloquent writer” and “strikingly attractive, with chestnut gold hair and violet eyes,” wrote Linda Kay in 2012 in The Sweet Sixteen: The Journey That Inspired the Canadian Women’s Press Club. Kay added that although Coleman was one of the top female journalists of her era, she likely only earned $35 a week at the peak of her career.

After a mysterious explosion rocked the American battleship Maine in Havana Harbor on Feb. 15, 1898, the U.S. planned to invade Cuba in response. It was a pivotal event in what became the Spanish-American War, and Coleman convinced the editor of The Mail and Empire to let her report from the front. Some considered the assignment a stunt to attract readers and Coleman was told to write “guff” as she called it.

She caught the night train to Washington, forced her way into the office of the Secretary of War and asked to sail with U.S. troops to Cuba. General Russell Alger told her she would not be allowed on any American ship. He laughed at the request in general, saying a war zone was no place for a woman, because, among other things, soldiers would be wandering around with their shirts off.

“I’m going through to Cuba, and not all the old generals in the old army are going to stop me,” Coleman insisted. Alger relented and signed the paperwork to make her an accredited correspondent. Although at least one other American female journalist, Anna Benjamin, and possibly another, went to Cuba, they had not been accredited.

But Coleman’s struggle wasn’t over once she had official approval. After waiting a week (some reports say six) in a dank hotel in Tampa, Fla., she was denied passage on the press boat to Cuba because the 134 male journalists and the army commanders were opposed to having a woman in their midst. She was also denied passage on a Red Cross ship leaving from Key West, Fla., reportedly because Clara Barton, a union nurse, took an instant dislike to her. So, Coleman was stranded in Florida, missing the front-line action.

But she eventually talked her way onto a U.S. government freighter carrying war supplies to Havana, and arrived in Cuba in July, just before the war ended. And Coleman wasn’t given any special allowances as a woman, often sleeping on the ground and eating when and where she could. When Coleman cabled back her first story to The Mail and Empire, it officially made her the first female accredited correspondent.

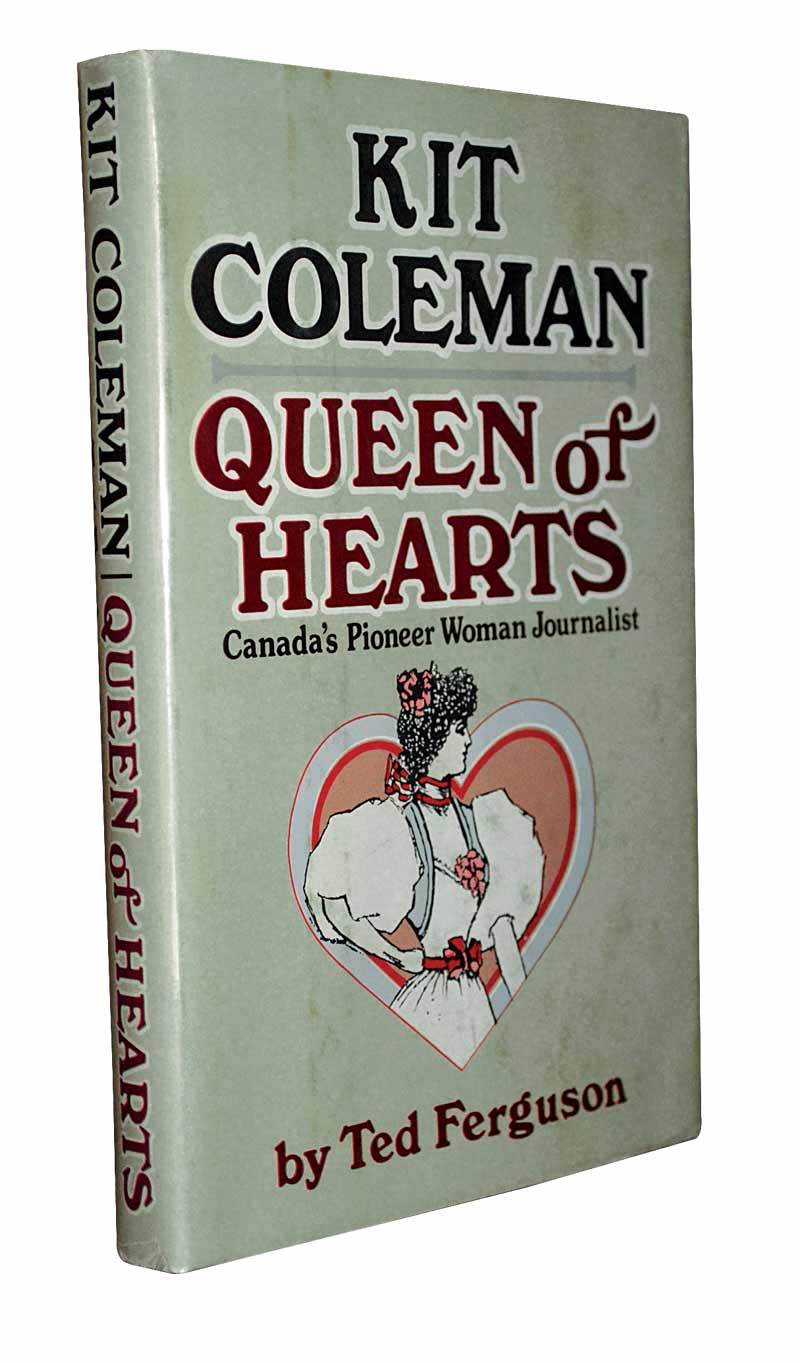

Coleman was a co-founder and the first president of the Canadian Women’s Press Club in 1904 and the subject of numerous biographies, including the 1978 book by Ted Ferguson, who called her writing “marvellously vivid.”[Doubleday Canada/AbeBooks.com]

Her reports were described as vivid, poignant accounts of the war. She wrote about the conflict’s human cost and aftermath and what the hostilities did to both soldiers and civilians caught in the crossfire. An interview with a U.S. military official also uncovered information about a secret arms shipment to Cuban rebels. The stories she filed from Cuba made her famous.

“Her writing was marvellously vivid,” declared Ted Ferguson of Coleman’s work as a war correspondent in his 1978 book Kit Coleman: Queen of Hearts.

Some examples: Coleman wrote that Spanish soldiers in a field hospital were “living ghosts of men” with “eyes sunken far in their sockets burning like lamps on the edge of extinction.” And following a crucial battle, she wrote: “Here in Santiago, men, nobles and commoners alike, dying in filth and stench, and uttermost squalor; lying out there on the hills for the buzzards and the crab to feed upon. There was heartbreak in the thought of it, in the sight of this hopeless suffering. We are very little creatures. Very small and cheap and poor.”

During her lifetime, the well-respected, groundbreaking journalist helped pave the way for other early female journalists.

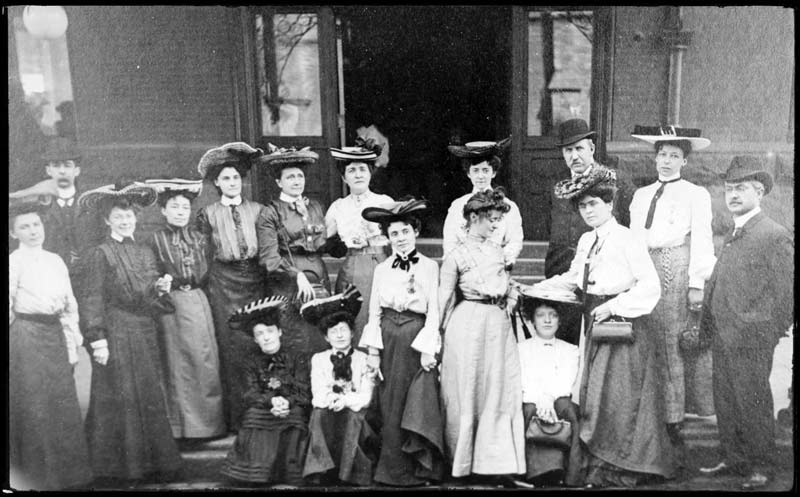

Coleman was a co-founder and the first president of the Canadian Women’s Press Club in 1904 [Margalo Whyte]

After a month in Cuba, Coleman returned to the U.S. on a troopship, helping to nurse wounded soldiers en route. General Alger invited her to go on a tour to be billed as the world’s first female reporter, before she went back to Canada. She agreed to address the International Press Union of Women Journalists in Washington, but declined a national tour.

While in the U.S. capital she also got married again—to Canadian doctor Theobald Coleman. They lived in Copper Cliff, Ont., (now Sudbury) before moving to Hamilton.

When Coleman returned to Canada, she adopted an anti-war stance. In addition to her war reporting, she had covered some significant news in her career, including a jailhouse interview with notorious fraudster Cassie Chadwick, an interview with French actress Sarah Bernhardt and reportage on the New York murder trial of railway baron heir Harry K. Thaw.

After a disagreement with the editor of The Mail and Empire in 1911, Coleman resigned and began selling her column to other newspapers across the country, making her the country’s first syndicated columnist. She charged $5 a column and earned more money than she had while at the Mail.

Coleman died of pneumonia in Hamilton in 1915. During her lifetime, the well-respected, groundbreaking journalist helped pave the way for other early female journalists such as Faith Fenton (also known as Alice Freeman), Ella Cora Hind and Miriam Green Ellis.

Wrote Barbara M. Freeman succinctly in a 1989 biography of Coleman: she “spent most of her 25 years as a journalist walking a creative tightrope between what was considered acceptable and what was considered too daring.”

Advertisement