Prime Minister Mackenzie King shares a private moment with his Irish terrier Pat. [Yousuf Karsh/Toronto Star/Digital Archive Ontario]

There is no doubt that Mackenzie King was an interesting man.

Case in point: Canada’s longest serving prime minister visited mediums to attempt to communicate with the dead, a roster that included political leaders, old friends and his mother. He apparently received reassurance more than advice and, as a bachelor without a partner to rely on for feedback, he needed it.

King was also obsessive, noting that the hands of the clock were together (or apart) when he made decisions and paying attention to the shapes he saw in his shaving cream or tea leaves in his cup. His succession of Irish terriers (all named Pat) were caressed, cossetted and revered. He kept a diary for more than 50 years, and this too filled the role of confidante, his way of indicating what he had done or, even more important, prevented each day.

But King wasn’t crazy. He was elected Liberal leader in 1919 in part because he had been loyal to Wilfrid Laurier during the debate about conscription during the Great War. That mattered with Franco-Quebecers. And he had written a book, the almost unreadable (and little read) Industry and Humanity, which made him an expert on the social unrest sweeping Canada after the First World War in the eyes of convention delegates.

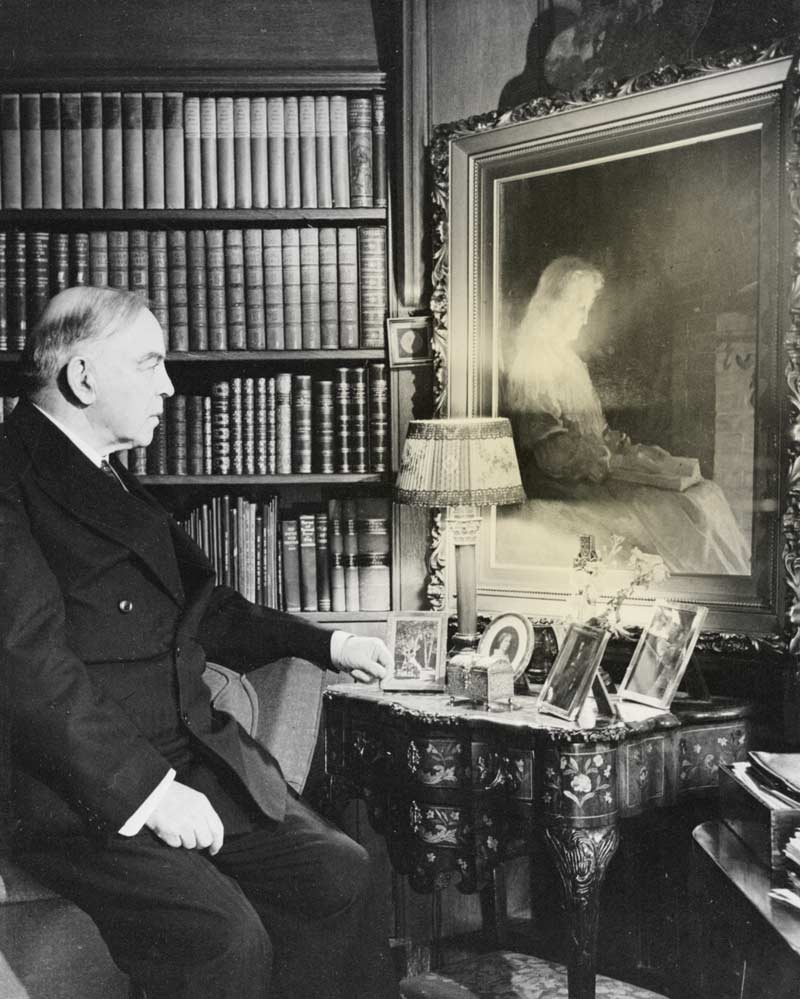

King gazes at a portrait of his late mother, whom he attempted to communicate with through a medium. [Gordon H. Coster/LAC/C-075053/Wikimedia]

Then, King won the 1921 election, narrowly lost four years later, but took power again in 1926. He was ousted in 1930, saddling the Conservatives with governing during the worst years of the Great Depression, but became prime minister again in 1935. King may not have had great charisma or a record of significant accomplishments for Canada, but he was a winner.

When the Germans invaded Poland at the beginning of September 1939 and Britain declared war on Sept. 3, King knew that Canada had to join the fight. He had, however, promised that “Parliament would decide,” and the country, while still a dominion of the British Empire, controlled its own foreign policy, thanks to the 1931 Statute of Westminster. So, Canada was not at war—yet.

Parliament did decide, and the country joined the conflict on Sept. 10. The delay, the pledges that this would be a war of “limited liability,” and that there would be no conscription for overseas service was significant, especially in Quebec, where most were not enthusiastic about fighting.

King’s policy, however, had made francophones willing to acquiesce to Canada becoming a belligerent, something most Anglo-Canadians wanted. National unity mattered to King and his Liberal party. He handily won re-election in March 1940 with 51 per cent of the popular vote and 179 of 245 seats in the House of Commons.

King poses with members of his cabinet in September 1939.[NFB/LAC/C-090191]

Conscription, an issue largely divided along English-French lines, was one of the PM’s greatest wartime challenges. [CWM/20010129-0610]

His wartime cabinet was strong, with powerful ministers given freedom to run their departments. Clarence (C.D.) Howe controlled wartime production. Ernest Lapointe was the Quebec lieutenant and, after his death in late 1941, Louis St. Laurent stepped into that role, and served as justice minister. Colonel J. Layton Ralston, a distinguished infantry officer during the First World War, led the Defence Department from 1940 to late 1944. James L. Ilsley was a capable finance minister, and Jimmy Gardiner oversaw agriculture.

And King’s key civil servants—Graham Towers at the Bank of Canada, Arnold Heeney in the Privy Council Office, Oscar D. Skelton and Norman Robertson at External Affairs, and Clifford Clark at Finance—provided the ideas that shaped the war effort. And transformed Canada forever.

But if limited liability had been King’s plan, it soon went out the window.

The Nazis invaded Denmark and Norway in April 1940, then the Low Countries and France in May. By early June, Britain was on the verge of defeat. The 1st Canadian Division in England was nearly the only equipped, though partially trained, force to resist what most saw as an inevitable German invasion of the island. The Canadian war effort now had to change.

Home defence conscription was enacted by the National Resources Mobilization Act in June 1940 and the first call-ups reported for duty in October. The navy sent everything it had overseas, the Royal Canadian Air Force deployed its few squadrons and the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan hastened its work. The army stepped up recruiting, creating battalions, brigades and divisions as fast as it could. Money, scarce during the Depression and tight in 1939-40, was now no object, and Canadian war industries ramped up to make everything from trucks and guns to ships and aircraft.

King and American President Franklin D. Roosevelt also made deals. First, the Ogdensburg Agreement, struck in August 1940, created a joint Canada-U.S. defence plan. Then, the Hyde Park Declaration the next year guaranteed that the two countries would work together on wartime production, and that Canada wouldn’t run out of American dollars to purchase what it needed.

King personally negotiated these two treaties with FDR, with whom he was friendly. And they were vital.

By 1943, Canada had become a military power.

Before the war, there had been 10,000 regulars in the three services. Now, Canada had the First Canadian Army in Britain, squadrons of aircraft operating in every theatre of the war, and the Royal Canadian Navy was fighting U-boats and guarding convoys.

Meanwhile, factories and farms were producing massive amounts of armaments and food.

Wages and prices were tightly controlled, taxes were increasing annually, and Canadians, with jobs available for everyone at home, were buying savings bonds in record numbers to pay for all the materiel. It was a total war, directed by King’s government.

But to many, total war meant conscription for service overseas. Most Conservatives were pushing for it, and some Liberals (including a few in cabinet) were as well. In early 1942, the prime minister decided to call a plebiscite with a somewhat indirect question—“Are you in favour of releasing the Government from any obligations arising out of any past commitments restricting the methods of raising men for military service?”—that amounted to a yes or no to compulsory service.

In Quebec, a substantial majority said no; a similar preponderance in the rest of the country said yes. King, though, said maybe, uttering perhaps his most famous quote in Parliament on June 10: “Not necessarily conscription, but conscription if necessary.”

How would he define necessity? Early that year, casualties were relatively low, and the army was not yet in sustained action (except for the disaster in Hong Kong and the imminent debacle at Dieppe), so there was little credible case for compulsory service. But most expected the casualties would come, not least in the RCAF, which had aircrew flying bomber raids over Germany, and the RCN, fighting U-boats in the North Atlantic.

In mid-1943, 1st Division and an armoured brigade landed in Sicily; in September they joined in the invasion of Italy, soon augmented by the 5th Armoured Division. Fighting at Ortona at Christmas was brutal, and the Italian Campaign ground slowly forward.

On June 6, 1944, the Allies invaded France, Canada’s 3rd Division and an armoured brigade played a critical role in the landings. During the next two months, the 2nd Infantry and 4th Armoured divisions entered the battle and casualties were heavy. Then the fighting to open the Scheldt estuary to ship traffic took place in October and into November, again with major losses. Some 5,000 were killed in Normandy and Canadians suffered another 6,000-plus casualties in the Scheldt fighting; Italy, too, was a drain on the infantry, with fierce combat needed to crack the Germans’ Hitler and Gothic lines. By the fall of 1944, there was a crisis at the front lines—and on the home front.

King, though, said maybe, uttering perhaps his most famous quote in Parliament on June 10: “Not necessarily conscription, but conscription if necessary.”

King meets with General Andrew McNaughton and officers of the Royal Canadian Artillery in August 1941.[DND/LAC/PA-142429]

The reinforcement stream created by the military had been based on estimates of losses. The planners had expected heavy infantry losses, as well as substantial numbers of support troop casualties from German air attacks. But, the Luftwaffe had essentially been driven from the skies and, so, there were more rear-area soldiers than needed, while infantrymen were in short supply. Where, the government asked its generals, could infantry be found? Only among the home defence troops was the answer.

King was horrified, believing the war to be almost won. Regardless, Defence Minister Ralston (and at least seven other ministers) were adamant that the home defence conscripts be sent overseas.

Brutally, King fired Ralston during a cabinet meeting, appointing General Andrew McNaughton in his place. The conscriptionist ministers sat stunned. McNaughton had led the army from 1939 to late 1943, and was not in favour of conscription. He set out to find volunteers among the home defence men—but failed.

The election victory was interpreted as recognition of King’s achievements in leading Canada to its astonishing war effort.

Family allowances were one of King’s top social welfare achievements. [CWM/20070104-009]

Soon, a few senior officers were speaking about the infantry shortages to the media, which King interpreted as signs of an emerging military revolt. He also sensed that he might lose the support of the pro-conscription ministers. On Nov. 22, 1944, he flip-flopped, announcing that 16,000 conscripts, enough to meet the infantry need, would be deployed overseas. Equally important, King held his cabinet and caucus together, losing only Air Minister Charles G. Power. The political crisis was over—and a winter hiatus in the fighting gave the army time to recover and fill its ranks again.

With the conscription issue settled, King could move on other matters that were important to him. He believed in the creation of the welfare state, and with an election due in 1945, he believed that new programs could help him woo voters. His government had put unemployment insurance into effect in 1940, one step in the larger plan.

Veterans Affairs Minister Ian Mackenzie, meanwhile, had also been working on creating benefits for servicemen and servicewomen and the Veterans Charter was ready to be unveiled. It offered everything from cash, clothing, education, training and land, to support to start a business and free medical care to those who had served. The initiative, vastly better than the treatment afforded Great War veterans, was as good as any plan for vets in the world, and far better than most. That women received equal treatment was also notable.

So too, was the fact that family allowances, the country’s first universal program, were paid directly to mothers. For some, the baby bonus was the only money that was theirs by right, and it won support across the country—although not to some Opposition critics who argued it would benefit Quebec’s large families and men who wouldn’t fight. Quebecers did tend to have large families, but the province’s military enlistment was some three times that of the First World War. Giving funds to mothers—the average payment per child was $5.94 (or about $100 today) per month—to spend on their children would help keep the economy going and help Canadian businesses and farmers, too.

King’s government was also preparing to deal with a much-feared postwar economic downturn. Canada’s gross national product had more than doubled during the conflict, but the end of munitions production and the return of men and women from overseas could have negatively impacted the gains. Large sums were devoted to building homes for vets, to supporting agriculture, and to helping businesses convert production lines for peacetime manufacturing. At the same time, bureaucrats readied plans for large government projects that could employ thousands.

“You socialists have schemes,” one Liberal MP told a Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) friend, “but I have the bills right here in my pocket.”

King called an election for June 11, 1945, a month after VE-Day, while the war against Japan continued and Canada was preparing to commit forces to an invasion of the country. That led the Progressive Conservatives to call for conscription for the Pacific; the CCF, meanwhile, expected to do well with its socialist platform.

King, however, campaigned, as he said, “in terms, not of promise, but of performance.” His candidates urged voters to “finish the job,” and called for national unity and social security. The result was close, King securing a slim majority with 118 seats; the Conservatives had 66 and the CCF 28. The Liberals won most of the military vote, too.

The victory was interpreted as recognition of King’s achievements in leading Canada to its astonishing war effort. King had kept the country united where Robert Borden, the Great War prime minister, had not. The nation King led produced enormous results on the battlefields, at sea, in the air, and in home-front factories and farms.

King was a leader when it counted most.

Advertisement