An Avro Lancaster bomber approaches RAF Colerne in England on June 6, 1944, in “Early Morning Arrival” by aviation artist Robert Taylor. [Robert Taylor/The Military Gallery, California, in association with Wings Fine Arts]

It was the night of April 27-28, 1944, and Lancaster R-ND 781/G of 622 Squadron, Royal Air Force, piloted by Flight Lieutenant James Andrew Watson of Hamilton, Ont., was on a bombing mission to Friedrichshafen, Germany.

R-ND would never reach its target, but Watson’s heroic actions that black night over occupied territory would inspire an unsuccessful campaign to award him a posthumous Victoria Cross.

The seven-member crew—three RAF, four RCAF—were at 17,000 feet as they approached the turning point, 30 minutes out, for their final run into the target. Suddenly, they were attacked from dead astern and below by three Junkers Ju-88 night fighters. It was about 1:30 a.m. and they were a little south of Strasbourg, France.

“The attack was a complete surprise, there was no moon, just complete darkness,” recalled Ron Hayes, the bomber’s mid-upper gunner. “The aircraft was equipped with H2S radar equipment which transmits pulses and the crew and Intelligence were not aware at the time that the Germans were able to home in on the signal.”

The crew could hear the thuds as the German rounds hit the rear of the aircraft and they saw flashes as the port elevator badly buckled. The rear gunner, RCAF Flight Sergeant Murdock MacKinnon—a Cape Breton native living in Somerville, Massachusetts, when he signed up—later reported that his radio and turret were knocked out.

RAF Sgt. Roy Clive Eames, flight engineer, said the initial attack had also penetrated the plane’s nose and knocked out its aileron and rear controls.

With MacKinnon out of commission, Hayes directed the pilot’s evasive actions. They were essentially flying blind, however. From his vantage point atop the Lanc, Hayes couldn’t see their attackers’ approaches and had to make his calls based on the tracers arcing past his canopy.

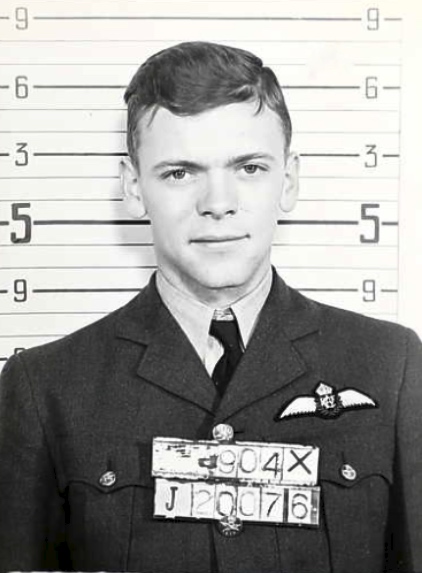

Flight Lieutenant James Andrew Watson of Hamilton, Ont., remained at the controls of his plummeting Lancaster to allow his crew time to bail out. [VAC]

Watson, at 21 among the eldest aboard and flying his 16th mission, side-slipped the big, lumbering plane to keep the flames at bay. But the maneuver amounted to a trade-off—the fire didn’t reach the crew but they were losing altitude fast.

“During this time the captain asked the navigator to inform the crew of our position for the purpose of escape,” MacKinnon reported later. “The navigator told us we were approximately on the French border.

“There was at no time any suggestion of panic and this was largely due to the coolness and perfect calm of our captain.”

Throughout the combat, Watson repeatedly asked for news of the rear gunner, with whom he’d flown all of his missions, and assured the rest of the crew that he would look after him. “Whatever happens, he’ll be OK,” the pilot assured them.

At the words ‘he’ll be OK,’” Eames said in a statement filed July 25, 1946, he realized “with horror…that Flt.-Lt. Watson would not leave that aircraft while there was the slightest doubt that a member of the crew remained [inside] and as a last resort would attempt a crash landing to save that member of his crew.”

“The attack was a complete surprise.”

As the fuselage seam aft of the burning engine began melting, Watson directed the crew to collect their parachutes. Soon, the wing was almost totally engulfed and a gaping hole was forming in the side of the plane.

“I’m sorry lads,” said Watson, “but you’ll have to hit the silk.”

“I then plugged into the intercom system and informed the pilot that…the rear gunner was still in his turret and I would let him know we were getting out,” said Hayes. “The captain’s last words to me were: ‘Yes, OK, but hurry, we’re at 4,500 feet; if he’s not hit he might make it. So long Ron, good luck.’”

Hayes, just 19 at the time, then opened the bulkhead door leading to the rear turret. MacKinnon turned his head and Hayes patted his parachute. The rear gunner turned away without acknowledging the news.

“The aircraft was now at about 4,000 feet when I bailed out,” Hayes said. “The pilot had the aircraft under perfect control, it was still losing height in a sinking fashion and the flames had enveloped the fuselage alongside the burning wing.”

In a report on the incident filed on May 6, 1945, weeks after they were liberated, MacKinnon said the Lancaster was badly damaged. Without intercom, he said he was “entirely ignorant of proceedings” until Hayes appeared.

“Starboard elevator in tail shot off,” reported MacKinnon. “Navigator [Flying Officer William Ransom of Hamilton) stated pilot was last seen holding stick hard to port.

“When I bailed out, the aircraft was a blazing mass in a dive so it seems impossible that pilot got out. I bailed out when flames were passing rear turret.”

As Ransom took his turn at the escape hatch, the third to go, he took one last look at Watson, whom he said was having “difficulty maintaining the aircraft in level flight.”

“Leaving the aircraft and releasing my parachute, I was able to watch the burning aircraft almost until it crashed,” Ransom later wrote. “It remained level, latterly, and in a shallow dive for much longer than would have been necessary for Flt.-Lt. Watson to reach the escape hatch and bail out, a fact which leads me to believe that he remained at the controls in order to allow the rear gunner, whom we were all under the impression was injured, as much time as possible to clear his turret.”

MacKinnon, he later learned, got clear “just in time to have his fall checked by his parachute before reaching the ground.”

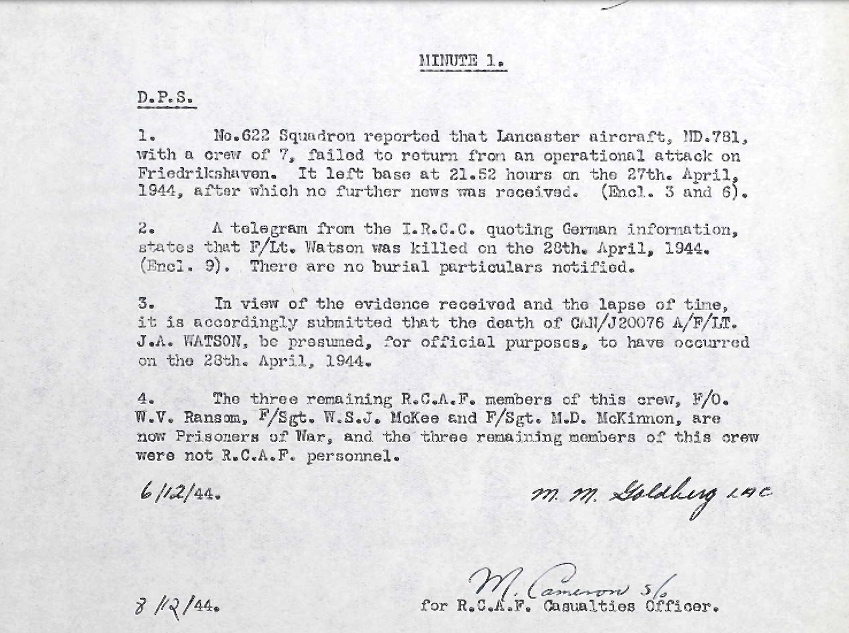

A casualty report from the last flight of Lancaster R-ND 781/G of 622 Squadron, Royal Air Force. [VAC]

“The action with the German fighter aircraft, the difficulty in evacuating our aircraft and the bail out and hard landing in the dark were very stressful experiences, and the right side of my body and lower back [were] aching,” he said.

Dizzy, Hayes rested for a few hours where he had landed, out in the open.

As daylight approached, he rose to search for a hiding place in a wood or a barn, but the pain was so bad he only managed to make it to a nearby ditch, where he was discovered by a local and taken to the Alsace village of Guémar.

He was interviewed by a young girl who could speak some English before he was taken to the village hall around 1 a.m. on April 28.

“Here I met a French schoolmistress, Mme. Lousie Strohl, who gave me tea, biscuits and tobacco, then she told me that Flt.-Lt. Watson had been found dead at the controls of the aircraft. She went to some length in describing him, even saying he was a Canadian and that he had two stripes on his epaulettes.

“This lady was sympathetic and wanted to cheer me up and make me feel at home, even though she could not help me escape. The village hall had become crowded with the local inhabitants who might have helped me escape if it was not for their fears of the Gestapo.”

A pair of Luftwaffe intelligence officers took Hayes to Colmar, France, for interrogation.

“After the usual questions, I was asked if I could help them in identifying the belongings of a dead pilot,” he said. “The items were those of Flt.-Lt. Watson in an envelope, consisting of his identification bracelet and a ring.

“I knew that the ring had been given to Jimmy Watson by his father. The Germans said that they had taken the articles from a…pilot who was found dead in the pilot’s seat of a Lancaster. I said nothing to them for fear that it might be the beginning of a long interrogation and I also knew that the identity bracelet was sufficient.”

Hayes surmised that Watson had died trying to save the rear gunner, MacKinnon. At Colmar, he saw three of his crewmates, but they didn’t speak to each other for fear the Germans might be listening.

He realized “with horror…that Flt.-Lt. Watson would not leave that aircraft.”

Eames and Hayes were taken to Stalag Luft VI, while officers Ransom and W.H. Russell were separated. On the way to the PoW camp, Eames told Hayes he had seen MacKinnon.

“Seeing him gave me a severe shock as I had convinced myself that he had been killed,” Eames reported.

In fact, all six crew who had escaped the burning plane had miraculously survived and were liberated in the spring of 1945. Hayes, an Englishman, would emigrate to Canada in 1951, largely based on the impressions left by his Canadian crewmates.

In a letter written while still a PoW in January 1945, Ransom asked his father, a padre at the Canadian Army Trades School, to “please see Jimmie’s folks and give them my deepest sympathy. He died like a hero in the fullest meaning of the word.

“He reached the ultimate in courage and devotion to duty that a bomber skipper can reach in that he gave his life that his crew might live, and he was successful, as all of us are safe. I am looking forward to meeting the parents of the grandest guy I’ve ever known—when this war is over.”

Eames called Watson “the bravest and coolest fellow I have ever met,” adding “we all owe our lives to him.”

In 1946 and 1947, five members of the crew put forward recommendations for the Victoria Cross to be awarded to their skipper.

“I firmly believe it would be impossible for an aircraft, in as badly damaged condition as was ours, to remain in such an attitude of flight without any assistance from the controls,” reported Ransom, who had flown many missions with Watson.

“I am convinced that on this occasion he unhesitatingly made his decision and at the cost of his own life remained at his post to ensure that his crew would have every possible opportunity and every valuable second of time to abandon the aircraft and save their lives.”

As daylight approached, he rose to search for a hiding place.

“It is quite clear,” said Hayes, “that Flt.-Lt. Watson sacrificed his life knowingly and willingly to ensure the safety of his crew. His most courageous act, his great and noble sacrifice in the face of the enemy was beyond the highest ideals of his duty and merits the highest possible award for gallantry and for valour in the face of the enemy.”

Watson’s nomination for a VC, however, went nowhere. He received only a mention in dispatches.

James Watson is buried at Choloy War Cemetery at Meurthe-et-Moselle, France, Grave No. 1A B23. A monument was dedicated on May 8, 2009, near the crash site in Saint-Hippolyte, France.

Advertisement