The feats of our secret agents in Europe during the Second World War were daring and the consequences of capture were torture and death (“Hush-hush heroes,” March/April). The story was very different in Asia, where the tropics were as formidable an enemy as the Japanese. And help was very, very far away.

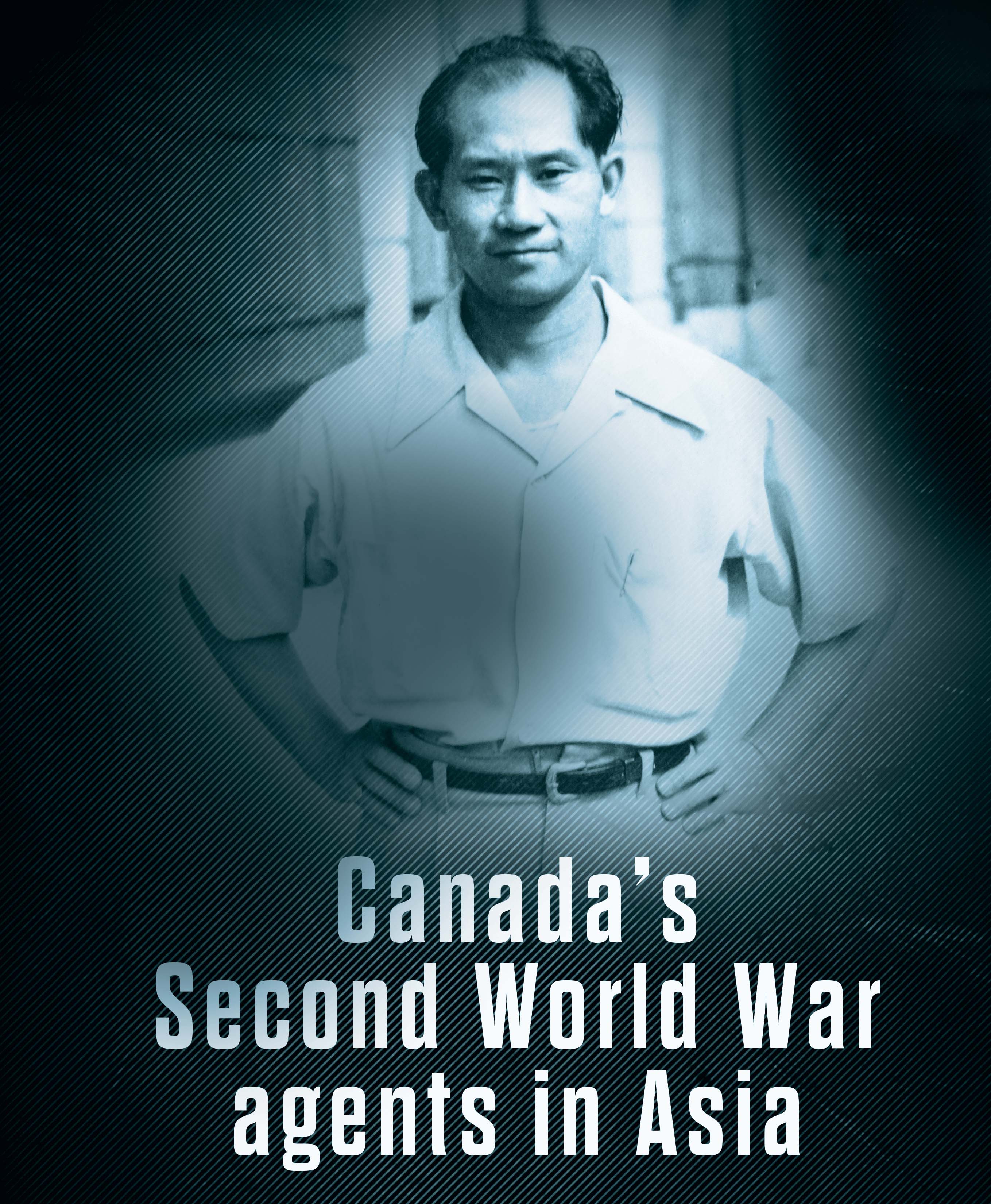

Agents in the Far East and the Pacific knew they had to rely on their own ingenuity to survive, ingenuity that saved Bill Chong, who was arrested with a companion by a Japanese patrol. They were asked whether they would rather be shot or beheaded—and forced to begin digging their graves. But the patrol leader ran out of patience. “Bullets cost money,” he said, ordering them to kneel and drawing his sword.

In desperation, Chong’s companion told the soldier to read the card in his pocket, a note written by his teacher at the Japanese school in Macau, a Japanese officer turned spy who used former pupils to gather information. Their captor read the note and let them go.

But Chong wasn’t working for the Japanese spy. He was working for the British.

Chong, from Vancouver, was in Hong Kong when the Japanese invaded in December 1941. In an interview with the Chinese Canadian Military Museum Society, he recalled the Battle of Hong Kong and reported seeing a wounded Canadian ask a Japanese soldier for water.

“I thought he would take the water bottle out. Instead, he took a pistol and shot him right there. I said, ‘How could people do that?’” There were more atrocities. “Finally I thought, ‘When is it going to be my turn?’ So, I decided to escape and went to free China and joined up with the British Army.”

Chong, code named Agent 50, spent more than three years behind enemy lines, dressed as a peasant, avoiding bandits and Japanese troops. He established a network that ran Red Cross supplies.

“Our organization was called the British Army Aid Group (BAAG) but we were doing intelligence actually.” BAAG, a unit of MI9 (the British Directorate of Military Intelligence Section 9), sent agents to gather military intelligence in southern China and Hong Kong and helped escaped PoWs and downed aircrew get to Allied Command headquarters in Chongqing, China. “Bill Chong was one of its most outstanding members,” Marjorie Wong wrote in The Dragon and the Maple Leaf: Chinese Canadians in World War II.

In addition to passing on information to BAAG, “they told me that I’m to rescue any person if they are British subjects,” Chong said. Altogether, BAAG is credited with helping PoWs, U.S. aircrew, Chinese and British armed services and more than 1,400 civilians escape.

“I brought out people from England, Australia, France, India…a lot of places,” he said. Chong is credited with hundreds of rescues, but “I never ask them for their last name. I never tell them who I am or what I am doing. All they know about me is to call me Bill.”

After the war, Chong was invited to observe one of the Hong Kong war crimes trials—and recognized the prosecutor and judge. “It was my job, I brought them home free.” The prosecutor Marcus da Silva had been arrested by the Japanese in May 1943. He had smuggled funds into a PoW camp so prisoners could buy extra food, and was suspected of spying.

“They gave me everything they had in the way of tortures and beatings,” da Silva said after the war. He was whipped, burnt with a hot poker, beaten and starved. Trading on information about a corrupt guard, Da Silva’s wife managed to get him released. In November 1943, Chong helped them escape to Macau—just ahead of a manhunt.

Although Chong had been born in Canada, like the hundreds of other Chinese-Canadians who served in all branches of the armed forces as volunteers and conscripts, he did not have the right to vote. Canadian-born Chinese as well as immigrants faced bigotry and economic discrimination. A head tax and the Chinese Exclusion Act blocked new immigrants and prevented Chinese-Canadians from bringing their families to Canada. In some provinces, they were barred from public pools, kept out of the professions, and given a fraction of the benefits granted to other Canadians.

Many saw military service not only as a patriotic duty but “also an affirmation of equality,” wrote Roy MacLaren in Canadians Behind Enemy Lines 1939-1945. After decades of treatment as second-class citizens, “they were ready, even eager, to fill all the obligations of citizenship so that in return they might receive all those rights which other Canadians took for granted.” Hundreds of Chinese-Canadians volunteered, many applying several times and to a variety of services after initial rejections. But in 1944, the need for manpower overcame prejudice and Chinese-Canadians began receiving conscription orders.

Once it entered the war, Japan quickly occupied British, French and Dutch colonies in Southeast Asia and was on the doorstep of India, Australia and China, which had been at war with Japan since 1937. Caucasians in occupied Asia were quickly rounded up and imprisoned or killed. Britain’s MI9 and Special Operations Executive (SOE) both faced obstacles in Asia. Few Europeans spoke languages of the Far East, and their physical features instantly gave them away. Many local populations mistrusted Europeans as much as the occupying force.

Thus was born the plan to plant Chinese-Canadian agents in Southeast Asia to work with guerrillas during the war.

“SOE recruited in waves, originally unsure that Chinese-Canadians could pass muster as commandos,” said Catherine Clement, curator of the Chinese Canadian Military Museum (CCMM) in Vancouver. “The first recruits were an experiment—13 hand-picked men, most of whom did not even know how to swim.” They were assigned to Operation Oblivion. They were told they had a 50-50 chance of survival, and were sworn to secrecy.

Army Captain Roger Cheng, the first Chinese-Canadian officer in Canada, was among the initial group for Operation Oblivion whose training began at a secret camp on Lake Okanagan in British Columbia. He became the leader. After commando and demolition training, they were schooled in jungle warfare. “We learned to climb and swing from tree to tree,” said Ed Lee, featured in Rumble in the Jungle, a recent exhibit on Force 136 at the CCMM. They also learned how to find food in the wild, to treat wounds and deal with jungle sickness, he said in a Memory Project interview.

On April 25, 1945, Operation Oblivion was scrubbed. The United States supported long-range air operations, the nationalist Chinese mistrusted British intentions, and many of the Allies were leery of working with communist guerrillas. Only a few of the original recruits ended up assigned to Force 136 operations behind Japanese lines.

Force 136 operatives worked in Sarawak in Malaysia, elsewhere on the island of Borneo, in British Malaya and in Burma, though only a dozen or so Chinese-Canadians saw combat service. Instead they trained and sometimes led local guerrilla groups in sabotage, reported on Japanese military activity, and helped downed aircrew and escaped PoWs to safety.

Ten of the 17 Canadians who survived undercover operations in France volunteered for SOE operations in French Indo-China, as did many Chinese-Canadians. Teams parachuted into Burma in the spring of 1945 to work with local tribes, destroying railways and wireless installations and escape routes to Thailand, bottling up Japanese troops fleeing in advance of the British army. (Force 136 exploits are “somewhat loosely portrayed,” in the film Bridge on the River Kwaii and formed the basis of Farewell to the King, Sean M. Maloney reported in the Canadian Military Journal).

Vancouver’s Neill Chan volunteered for a Burma assignment. “I wasn’t nervous at the start of that trip,” he recently told the Vancouver Sun, “but by the end, I was very scared. The locals thought I was a spy. I was told they would shoot me.” He was unnerved by seeing bodies in a ditch. “They had been decapitated.”

Burma claimed the only Canadian Force 136 fatality—Jean-Paul Archambault of Montreal, who had also served for seven months in occupied France. Preparing to sabotage a railway bridge, he accidentally detonated explosives he had been drying out. Wounded, with no hope of medical treatment or rescue, he died two days later.

More than 150 Force 136 agents, including some Canadians, were sent into British Malaya and Borneo to work with the Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army and local tribes.

Ernie Louie, one of the few Oblivion recruits deployed on another mission, parachuted into Johore, north of Singapore, on Aug. 5, 1945, as part of an all-Canadian Force 136 team to train and support local guerrillas, sabotage transportation routes and report on Japanese movements. Two team members, Joseph Henri Adélard Benoit and Roger Caza, had also served with SOE in France.

The guerrilla camp was located about 120 kilometres away, normally a three-day march. “But it lasted seven nightmarish days,” said Louie. “For three full days, it poured rain and our boots disintegrated.” They arrived covered in leech bites and jungle sores.

Five of Operation Oblivion’s original recruits—Cheng and Jim Shiu, Norman Low, Roy Chan and Louey King—were sent to Sarawak, which had been seized by the Japanese in January 1942. Accounts of their experiences can be found at Veterans Stories on the CCMM website.

The tribes were bitter after four years of occupation during which the Japanese had commandeered their crops and forced them to hunt to feed the occupiers. The Canadians’ mission was to work with Dayak headhunters to force a surrender. The Dayaks were thrilled to co-operate—it meant the ban on headhunting was lifted—at least for Japanese targets.

The Canadians were prepared for anything. “One thing I promised myself—not to be taken alive,” said Roy Chan. “If I am captured alive, I know I die a thousand deaths. So, I put myself out of misery by having two extra bullets in one pocket for myself.”

The team arrived on Aug. 6, 1945, the day all SOE and MI9 missions in Southeast Asia changed. The day the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima.

From that date, SOE and MI9 were more concerned with the welfare of the 300,000 PoWs and maintaining order until government could be re-established. It was still a hardship assignment. “We lived on crocodile meat, monkeys and wild pig,” recalled King. It was incredibly hot and steamy there, often over 45°C.” They had to deal with Japanese who stubbornly held out after the surrender, Japanese guards they feared would massacre whole camps, and local tribes bent on taking retribution on surrendered Japanese.

As in Europe, the contribution to the war effort of SOE and MI9 operatives in Asia belies their small number.

“SOE-led guerrilla groups killed more Japanese forces than the regular army,” Colonel Bernd Horn wrote in A Most Ungentlemanly Way of War: The SOE and the Canadian Connection. “One guerrilla force alone is credited with killing an estimated 10,694 Japanese soldiers.”

But perhaps the greatest contribution was in keeping the lid on a volatile situation that could have become a bloodbath after the formal war stopped.

In late August 1945, MI9’s Arthur Stewart, a Vancouverite who had worked with guerrillas in the jungle in Burma, was sent to Singapore to lead a hard-working team of E Group and Force 136 operatives to ensure the safety of prisoners of war. (Vancouver’s Bill Lee, who had the only radio link in the area, worked 20 hours a day encoding, transmitting and decoding messages).

Stewart visited all the camps around Singapore, collected prisoners’ names, and arranged for drops of food and medicine. He was awarded the Order of the British Empire, credited not only for bravery and meeting the urgent requirements of thousands of PoWs, but keeping “the conduct of the Japanese forces in Singapore…well under control.”

After the war, some of the Canadian SOE and MI9 operatives went on to public lives. Allyre Sirois became a lawyer and judge of the Court of Queen’s Bench in Saskatchewan; Douglas Jung was the first member of a visible minority elected to Parliament and served as a delegate to the United Nations. And many Force 136 recruits fought for citizenship and voting rights for Chinese-Canadians.

But most returned to their everyday lives. Bill Chong was awarded the British Empire Medal for meritorious civil or military service in 1947 and continued working for British intelligence for a decade after the war. After returning to Canada, he opened a cafe in Chemainus on Vancouver Island. Ernie Louie and his brothers founded drug store and grocery store chains. Guy d’Artois continued his military career, went on to serve in Korea, and married his British sweetheart Sonia Butt, herself a heroine of the SOE, who took on the role of wife and mother.

Sworn to secrecy, SOE and MI9 veterans did not even tell their families of their exploits during the war.

“They said, ‘Your job is finished. You forget where you’ve been.’” Roy Chan said in postwar interviews. “So when we went back home, we never tell them where we’ve been. My mother and brother they thought all the time I’m in Australia, I was training all the time.”

The historical record is sparse, too. “Unless a secret service remains secret, it cannot do its work,” wrote M.R.D. Foot in his history of the SOE in France. To minimize security risks, field notes were not kept, headquarters paperwork was kept to a minimum and after the war, records were often trashed, he said. And by the time historians started telling their stories, a number of the veterans had already died.

Now there are very few left to tell a new generation the tales of Canada’s hush-hush heroes who so bravely operated behind enemy lines in Asia and Europe in a now-distant war.

Top photo: Code named Agent 50, Bill Chong risked his life behind Japanese lines.

Advertisement