Family and cultural ties between Nova Scotia and New England, for example, were strong, and remain so. To this day, you’d swear by the accents along parts of Nova Scotia’s South Shore that you were in New York or Massachusetts.

A half-century after that first union between provinces, when the munitions ship Mont-Blanc blew up in Halifax Harbour after colliding with the relief vessel Imo on Dec. 6, 1917, it was Bostonians and the people of Massachusetts who led the way in flooding the city with aid and supplies. They were also among the last to leave.

As a thank you, Nova Scotia sends Boston a Christmas tree each year. It is decorated and lit during an elaborate ceremony on the Boston Common on the first Thursday after each American Thanksgiving.

Less than an hour later, the offices of Hornblower and Weeks, a Boston investment banking firm, received a cryptic telegram which, given the state of the city from which it came, was no minor miracle in and of itself.

The message was sent by George Graham, the company’s man in Halifax, to James J. Phelan, a partner in the firm. It summarized the disaster that had befallen the Nova Scotia port city and issued a call to action.

“Organize a relief train and send word to Wolfville and Windsor [N.S.] to round up all doctors, nurses, and Red Cross supplies possible to obtain,” it said. “Not time to explain details but list of casualties is enormous.”

Graham’s telegram set the city of Boston and state of Massachusetts on a course that would cement the ties between the two cities well into the 21st century. A relief team was assembled, money was raised, and it all went to Halifax, pronto.

Phelan was attending a meeting at the Massachusetts State House on Dec. 6 as part of his work on the governor’s committee on public safety, which had been created to organize, supervise, direct and co-ordinate local public-safety committees across the state during the First World War.

According to an account published by the New England Historical Society and other sources, Phelan received a mid-meeting phone call with news of the telegram and immediately left the room for the governor’s office down the hall.

Governor Samuel McCall, a long-time congressman and newspaper editor, was unable to clarify the situation through his own extensive connections, so he dispatched a message of his own to the mayor of Halifax, Peter Martin.

“Understand that your city in danger from explosion and conflagration,” it said. “Reports only fragmentary. Massachusetts ready to go the limit in rendering every assistance you may be in need of. Wire me back immediately.”

Committee members contacted their connections at banks, railroads and universities. Harvard emptied its medical school and, with the Red Cross, assembled portable surgical suites. Nurses volunteered. Banks put up cash.

The head of the Boston and Maine Railroad promised a train if the governor could fill it.

Later that afternoon, McCall sent a second telegram to Mayor Martin, recorded in the U.S. Library of Congress: “Since sending my telegram this morning offering unlimited assistance an important meeting of citizens has been held and Massachusetts stands ready to offer aid in any way you can avail yourself of it. We are prepared to send forward immediately a special train with surgeons, nurses and other medical assistance, but await advice from you.”

There was no reply. The train left for Halifax at 10 p.m., even though those aboard still had no firsthand information beyond Graham’s cryptic telegram less than 12 hours earlier.

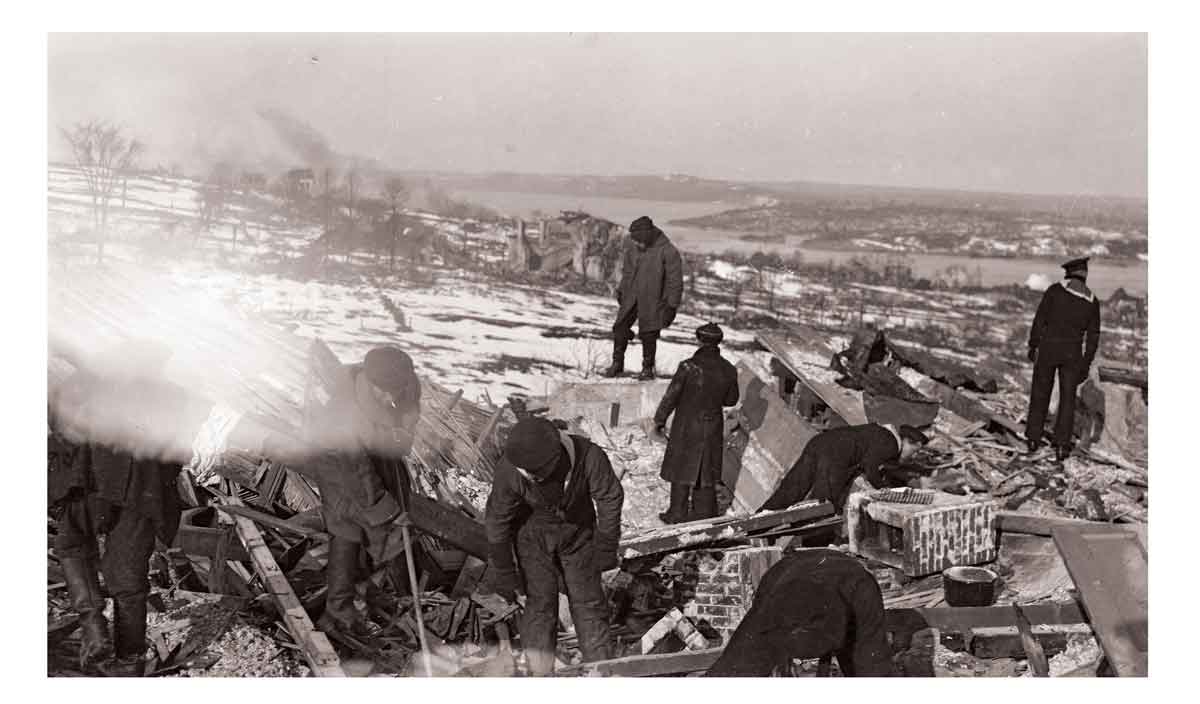

The train was delayed en route by a breakdown and blizzard that set in on the evening of Dec. 6. It arrived in Halifax early Dec. 8. The volunteers immediately began distributing food, water and medical supplies. Doctors and nurses relieved exhausted medical staff who had been working without rest since the explosion.

A second train was dispatched by the Boston chapter of the Red Cross. Among those aboard was an ophthalmologist to help treat the myriad of eye injuries sustained largely by onlookers who had been watching the Mont-Blanc fire through windows when the ship exploded.

Back in Boston, McCall formed the 19-member Massachusetts-Halifax Relief Committee. Phelan was appointed vice-chair. Its first meeting was held at 10 a.m., Dec. 7, after which it issued a call to the people of Massachusetts.

“Later will come the great work of rehabilitation to which we are all committed as near neighbors of the stricken city. Cash will be required to do all this, and Massachusetts may be called upon for a million dollars. Everybody is asked to subscribe generously and as quickly as possible.”

The new committee chair Henry B. Endicott then wired local public-safety subcommittees statewide urging them to get on with the task of fundraising.

Committee members began assembling a warehouse full of relief supplies. They collected furniture, kitchen goods, food, bedding, lumber—much of what was needed to rebuild the devastated city and care for its residents. The warehouse and goods cost $500,000 (worth more than $8 million in 2019).

They loaded the materials onto a ship, the SS Calvin Austin, that left on Dec. 9 for Halifax, where a store was set up for displaced families to visit and take what they needed to rebuild their lives.

The $300,000 ($4.8 million today) worth of inventory in that first shipload included 985 packages of mattresses, 591 cots, 86 bundles of pillows, 200 bags of flour, 115 cases of canned beef, 200 cases of canned beans, 62 cases of coffee and 26 cases of tea. There were shoes, crackers, glass for windows, roofing, clothing, bread, even margarine.

The Boston Symphony Orchestra performed a benefit concert for Halifax in the days following the catastrophe. Ten trucks, worth US$25,000 apiece at the time, were shipped as gifts from the state of Massachusetts to the city of Halifax.

Gradually communication lines were restored, and words of thanks came from Halifax to Boston. There was also a Jan. 12, 1918, plea to hold off on sending more food, clothing or medical personnel until further notice, “on account of the great congestion and impossibility of properly handling the goods on arrival.”

Abraham C. Ratshesky, the commissioner in charge of the Massachusetts relief expedition, filed a detailed report to the governor in 1918 describing his first impressions of Halifax as he was taken to City Hall by a driver who had lost his wife and four children in the blast—“a gruesome start,” the commissioner called it.

“An awful sight presented itself,” wrote Ratshesky. “Buildings shattered on all sides; chaos apparent; no order existed.”

Temporary housing was built, including the 320-unit Governor McCall Apartments on the newly created Massachusetts Avenue.

In the devastated north-end neighbourhood of Richmond, new homes were built and furnished, partly by the hands of Boston labour and largely with monies raised by the Massachusetts-Halifax Relief Committee.

The distinctive new neighbourhood of 832 row houses and duplexes was the product of a collaboration between Thomas Adams—an English pioneer of modern urban planning—and Montreal architect George Ross. Named the Hydrostone for the fireproof concrete blocks used to build it, the district with its boulevards and small, solid homes, is now a gentrified national historic site. It remains one of the more prominent physical legacies of the disaster.

The Bostonians worked with the Halifax Relief Commission for six more years to help survivors and improve health conditions in the city. Their legacy included long-term aid to those stricken by blindness and tuberculosis. The Massachusetts-Halifax Relief Committee’s donations totalled $716,000 ($11.5 million today), all of it contributed.

In 1971, the Lunenburg County Christmas Tree Producers Association began annual donations of a large tree to promote Christmas tree exports as well as to acknowledge Boston’s support after the explosion. The practice was later taken over by the Nova Scotia government.

The gift is Boston’s official Christmas tree and holds a prominent place on the Boston Common throughout each holiday season. The Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources has specific guidelines for the tree. It must be an attractive balsam fir, white spruce or red spruce, 12 to 16 metres tall, healthy with good colour, medium to heavy density, uniform and symmetrical and easy to access.

“To our friends from Nova Scotia,” said Mayor Martin J. Walsh at the 2019 event, held Dec. 5, “thank you for being incredible friends and partners for many years.

“God Bless You.”

Advertisement