PoWs turned scraps into works of art

Few artifacts survive to remind us of the fate of Canadians who fought in the Battle of Hong Kong, the then British colony that surrendered to the Japanese on Christmas Day, 1941, after a fierce, 17-day battle.

The Winnipeg Grenadiers and Royal Rifles from Quebec City were sent to join 14,000 Allied defence troops, who were no match for the 52,000 seasoned, heavily armed Japanese invaders. The Canadian contingent was undertrained, under-armed, and their transport and heavy equipment never arrived.

Every one of the 1,975 Canadians became a casualty of war: 290 were killed, 493 were wounded, and everyone who survived the battle was taken prisoner. Survivors spent 44 months as prisoners of war, during which 260 of them died, almost as many as were killed in battle.

An enlistment poster used in reconstituting the regiment after it was decimated in Hong Kong. [The Manitoba Museum/H9-37-547-a-ag]

Life in the PoW camps was brutal and miserable. Prisoners were starved, beaten, terrorized and used as slave labour in Japanese mines, dockyards, airfields and railways. Their camps were filthy and infested with lice, bedbugs and millions of flies.

Living on as little as 600 calories a day, they became walking skeletons. Always hungry, they fell victim to diseases like dysentery, diphtheria and cholera, which arose from unsanitary conditions, and vitamin deficiency diseases like beriberi, pellagra and blindness.

The mail was unreliable and slow. In May 1942 a few prisoners were allowed to write home—but most letters took more than a year to reach their families. Many letters, stored or destroyed by the Japanese, never arrived at all. Few parcels ever reached Hong Kong PoWs; their captors sold them on the black market or kept them for their own use.

PoWs weren’t allowed to take much with them to the camps, and possessions were confiscated or stolen. “Things got pretty bad,” said Roland Sawatzky, curator of history at The Manitoba Museum, which contains some of the artifacts. “The few things they did have were very important to them and they kept them throughout their lives.” The museum has camp toilet paper and a pair of underwear, patched so many times “it looks more like a rag than clothing,”

HMCS Prince Robert crew liberated British and Canadian Hong Kong PoWs in 1945. [PO Jack Hawes/DND/LAC/PA-145983]

Grenadier Lieut. Richard Maze treasured a handmade chess set and cigarette case. In Shamshuipo camp he experienced his share of sickness and brutality. Sick with dysentery, he once responded slowly to a roll call, and was pummeled in the face. But Maze was made of stern stuff: he died in Chilliwack, B.C., in 2010, aged 99.

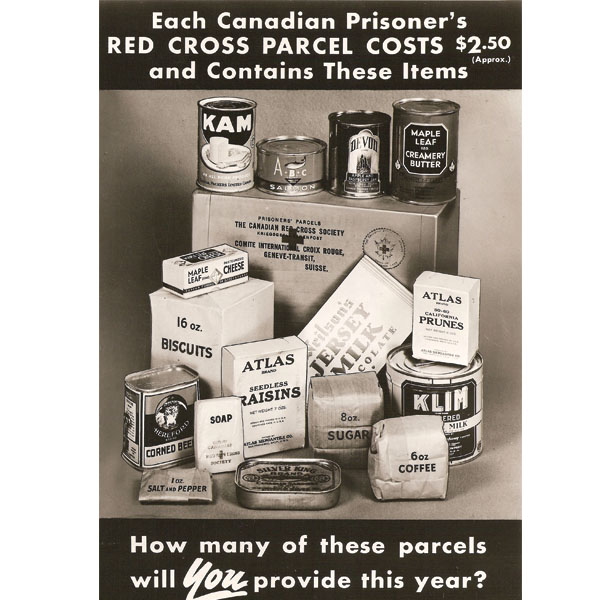

Japanese captors filched or stored Red Cross parcels, so few made it to suffering PoWs. [Canadian Red Cross]

The objects, fashioned by fellow prisoners in handicraft competitions organized to keep up morale and stave off the boredom of captivity, are made from scrounged wood scraps. The two-centimetre tall chess pieces have thin pegs to secure them to the board, which is made of inlaid bamboo.

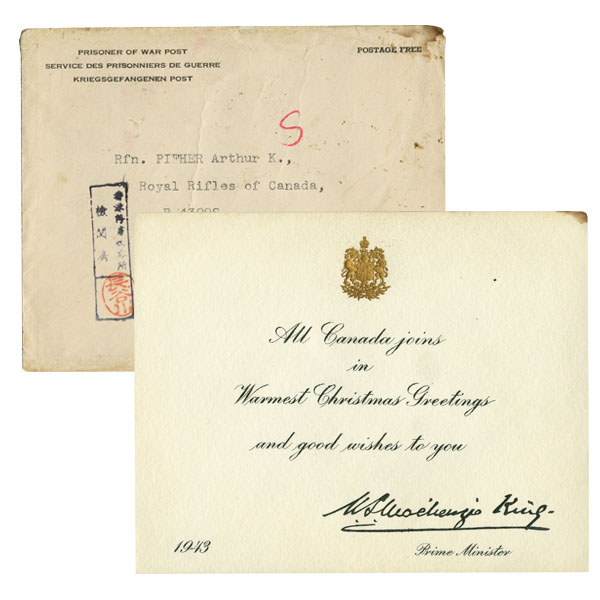

Prime Minister W.L. Mackenzie King sent Christmas cards to PoWs. The few that made it through in Hong Kong were treasured. [Bill Kent/CWM/20130015-001]

Arthur Pifher, of the Royal Rifles, kept a Christmas card sent to him in 1943 by Prime Minister W. L. Mackenzie King. Though hundreds were sent out, only a few were delivered to prisoners. Pifher kept his for 69 years, and presented it in 2012 to Prime Minister Stephen Harper, who donated it to the Canadian War Museum.

The Grim Tally

• 1,975 deployed

• 290 killed

• 493 wounded

• 1685 captured

• 260 died in PoW camps

Advertisement