Japanese Admiral Saburō Hyakutake served as Hirohito’s grand chamberlain from 1936 to 1944. [Wikimedia]

But the newly released diaries of one of his closest aides suggest the emperor posthumously known as Shōwa thought war with the West was inevitable and was preparing for it earnestly two months before Japan attacked Pearl Harbor.

Relatives of Admiral Saburō Hyakutake, who served as the emperor’s grand chamberlain and managed the royal household, deposited 25 of his diaries and pocket notebooks, along with memos he wrote, to the library at the University of Tokyo’s graduate schools for law and politics. They became available to the public in September.

Hirohito escaped a war crimes trial based on the public premise that he had resisted ratcheting up Japan’s aggression in the Pacific, where it had been expanding its territories since 1932 and fighting the Sino-Japanese War since 1937.

But Hyakutake’s diary entries cast the emperor, considered a living god by Japanese at the time, as conflicted and ultimately a strong proponent of war with the West.

On Oct. 13, 1941, he quoted two government ministers describing Hirohito’s shifting attitude as more hawkish even than his own admirals and generals.

Hyakutake wrote that he heard Tsuneo Matsudaira, the imperial household minister, say after an audience with Hirohito: “The emperor appears to have been prepared for war in the face of the tense times.”

The entry also says the interior minister, Kōichi Kido, was concerned that that the emperor was running ahead of his aides on the matter of war. “I occasionally have to try to stop him from going too far,” Kido was quoted as saying.

Japan was suffering under a U.S.-led oil embargo, imposed days after Japanese forces formally occupied southern Indochina on July 28, 1941. The Americans had supplied 93 per cent of Japan’s oil in 1940, so the measures hit hard.

In the hawks’ minds, a successful attack on Pearl Harbor would, among other things, prevent the U.S. Pacific fleet from interfering in Japanese conquests of oil-rich British, Dutch and American territories in Southeast Asia.

The USS Shaw explodes during the Battle of Pearl Harbor. [U.S. Archives/Wikimedia Commons]

He attempted to talk General Hideki Tojo, the army minister, out of his pro-war stance and into giving in to American demands to withdraw Japanese troops from China and French Indochina, but was unsuccessful.

Konoe and his cabinet resigned on Oct. 16, three days after Hyakutake recorded the two ministers’ impressions of Hirohito’s position in his diary.

The outgoing prime minister recommended Hirohito’s uncle-in-law, Prince Naruhiko Higashikuni, an army general, to succeed him. The emperor instead appointed the pro-war Tojo two days later.

“I actually thought Prince Higashikuni suitable as chief of staff of the army,” Hirohito acknowledged after the war. “But I think the appointment of a member of the imperial house to a political office must be considered very carefully.

“Above all, in time of peace this is fine, but when there is a fear that there may even be a war, then more importantly, considering the welfare of the imperial house, I wonder about the wisdom of a member of the imperial family serving [as prime minister].”

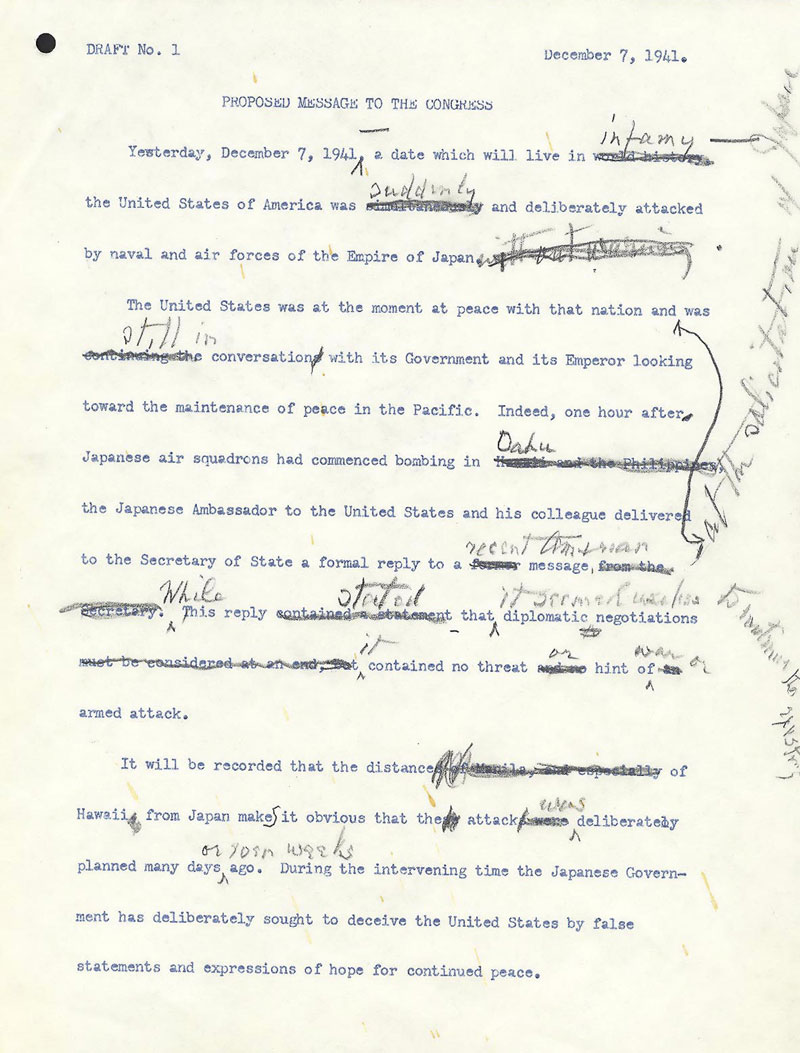

Annotated draft of U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “Day of Infamy” speech, delivered to a joint session of Congress on Dec. 8, 1941. [Franklin D. Roosevelt Library/U.S. National Archives and Records Administration]

Kido apparently asked Hirohito “to say things to give the impression that Japan will exhaust all measures to pursue peace when the foreign minister is present.”

Konoe later described Hirohito as initially “a pacifist [who] wished to avoid war,” but said his position evolved until he eventually came around to the idea, pushed by his military leaders, that war with the West was the only way forward.

“When I told him that to initiate war was a mistake, he agreed,” Konoe told his secretary, Kenji Tomita. “But the next day, he would tell me: ‘You were worried about it yesterday but you do not have to worry so much.’

“Thus, gradually he began to lead to war. And the next time I met him, he leaned even more to war. I felt the emperor was telling me: ‘My prime minister does not understand military matters. I know much more.’ In short, the emperor had absorbed the view of the army and the navy high commands.”

Diplomacy had ended and hostilities could commence at any moment.

Konoe forcefully reiterated his objections during a luncheon with the emperor and all living former prime ministers eight days before the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Despite the apparent momentum toward war, Japanese ministers and diplomats continued making overtures to Washington virtually until the morning of the Pearl Harbor attack, when Japan’s ambassador to the United States was dispatched to deliver a 5,000-word notification that diplomacy had ended and hostilities could commence at any moment.

The 14-part message took too long for Japanese embassy staff to translate, however, and it was not delivered by ambassador Kichisaburō Nomura and special envoy Saburō Kurusu until an hour after the attack had begun. The document contained no formal declaration of war, nor did it sever diplomatic relations.

“The earnest hope of the Japanese Government to adjust Japanese-American relations and to preserve and promote the peace of the Pacific through cooperation with the American Government has finally been lost,” it concluded.

“The Japanese Government regrets to have to notify hereby the American Government that in view of the attitude of the American Government it cannot but consider that it is impossible to reach an agreement through further negotiations.”

In addition to Pearl Harbor, Japanese forces launched co-ordinated attacks over seven hours on the U.S.-held Philippines, Guam and Wake Island and on the British Empire in Malaya, Singapore and Hong Kong, where 290 Canadian troops were killed and 493 wounded before the colony fell on Christmas Day. Some 1,685 were taken prisoner, suffering years of hard labour, abuse and starvation; 267 died.

Later, upon hearing of the Pearl Harbor attack, Konoe said: “What on earth? I really feel a miserable defeat coming; this will only last two or three months.”

It took six. At the Battle of Midway in June 1942, the tide of war in the Pacific took an abrupt turn after the Americans sank the Japanese heavy cruiser Mikuma and four of the six fleet aircraft carriers that had launched the Pearl Harbor attack. Historian John Keegan called it “the most stunning and decisive blow in the history of naval warfare.”

U.S. Lieutenant-General Richard K. Sutherland looks on as Japanese foreign affairs minister Mamoru Shigemitsu signs the Instrument of Surrender aboard the USS Missouri on Sept. 2, 1945. [Wikimedia Commons]

Admiral Hisanori Fujita, who succeeded Hyakutake as grand chamberlain in August 1944, reported that the emperor was intent on seeking a tennozan (great victory) and firmly rejected Konoe’s recommendation.

Konoe served in the postwar cabinet of Prince Naruhiko—the last Imperial Japanese officer to serve as prime minister—but he resigned after refusing to sign on to Operation Blacklist, a U.S. plan to exonerate the emperor and the imperial family of criminal responsibility.

He died peacefully in 1989 at age 87, after 62 years on the throne.

The former prime minister was then investigated for war crimes. When the Americans issued a last call for alleged war criminals to report in December 1945, Konoe took potassium cyanide and killed himself.

While Tojo and other Japanese war criminals either committed ritual suicide or were hanged after they were convicted by war crimes tribunals, Hirohito lived another 40 years. He died peacefully in 1989 at age 87, after 62 years on the throne.

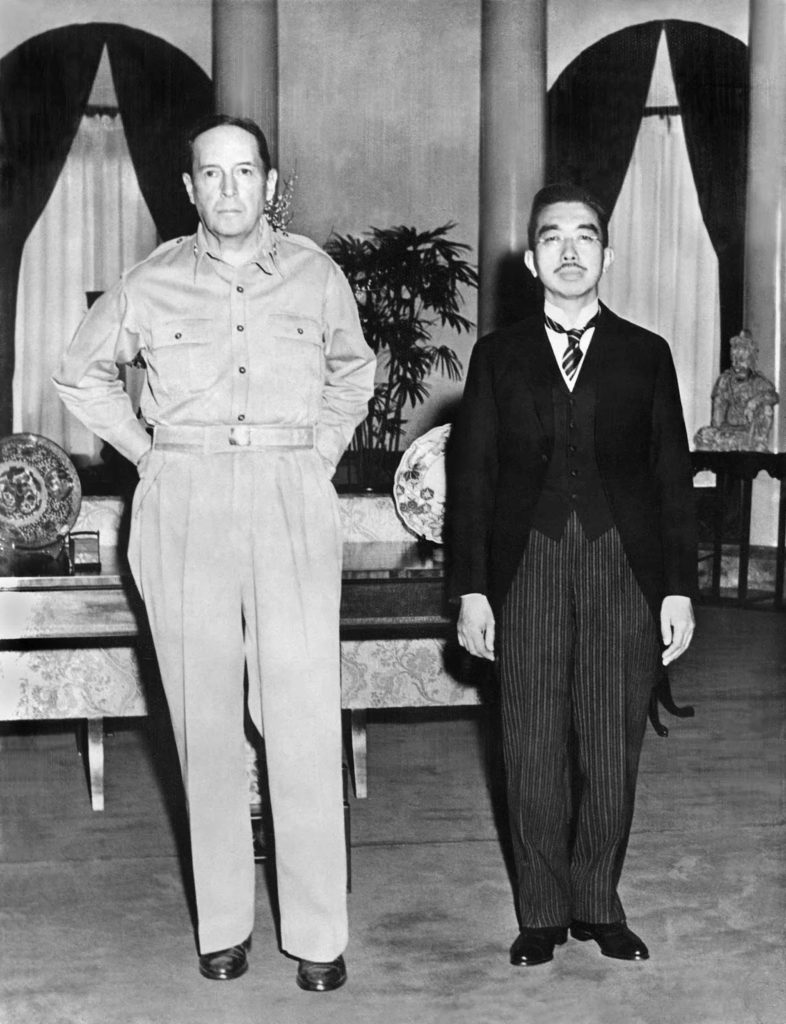

U.S. General Douglas MacArthur and Emperor Hirohito. [Life Magazine]

This was thanks largely to U.S. General Douglas MacArthur, who served as Allied commander of the Japanese occupation—the man who moulded Japan in America’s own image, transforming it into a democracy and helping set it on the path to recovery and technological dominance.

MacArthur reported to Washington in January 1946 that indicting the emperor would “unquestionably cause a tremendous convulsion among the Japanese people, the repercussions of which cannot be overestimated.”

“He is a symbol which unites all Japanese,” he wrote. “Destroy him and the nation will disintegrate…. It is quite possible that a million troops would be required which would have to be maintained for an indefinite number of years.”

MacArthur had one of his staff, Brigadier-General Bonner Fellers, tell Admiral Mitsumasa Yonai in March 1946 that “it would be most convenient if the Japanese side could prove to us that the Emperor is completely blameless,” suggesting that the coming trials offered the best opportunity.

“Tojo, in particular, should be made to bear all responsibility at his trial,” Fellers told him. “I want you to have Tojo say as follows: ‘At the imperial conference prior to the start of the war, I already decided to push for war even if his majesty the emperor was against going to war with the United States.’”

Sparing the emperor ingratiated MacArthur, and his mission, to the Japanese people. Thus, the colourful, pipe-smoking general resisted any suggestion of eliminating the Japanese monarchy or having Hirohito step down, much less subjecting him—and the Japanese citizenry—to the indignity of a war crimes tribunal.

He did insist Hirohito surrender the imperial claim of divinity, ostensibly to make way for separation of church and state—an easy sell, it turned out, since Hirohito never considered himself a deity. The new constitution adopted in 1947 reduced the emperor’s role from imperial sovereign to constitutional monarch and to head of state, not government.

Japanese citizens kneel and listen to a radio in Tokyo as Emperor Hirohito announces the end of the war. [Kyodo News]

In it, the emperor praised Japan’s Axis and other allies for their consistent co-operation “towards the emancipation of East Asia.”

The emperor agonized until his death about his responsibility for the bloody war.

“We declared war on America and Britain out of our sincere desire to ensure Japan’s self-preservation and the stabilization of East Asia,” he said.

“The war situation has developed not necessarily to Japan’s advantage, while the general trends of the world have all turned against her interest.

“Moreover, the enemy has begun to employ a new and most cruel bomb, the power of which to do damage is, indeed, incalculable, taking the toll of many innocent lives. Should we continue to fight, it would not only result in an ultimate collapse and obliteration of the Japanese nation, but also it would lead to the total extinction of human civilization.”

The last of Hirohito’s chamberlains, Shinobu Kobayashi, wrote in his diaries that the emperor agonized until his death about his responsibility for the bloody war in the Pacific.

In an entry from April 7, 1987, less than two years before Hirohito died, Kobayashi quoted his boss as saying he had been “told about my war responsibility” and did not see any point in living longer because it would “only increase my chances of seeing or hearing things that are agonizing.”

“Only a few people talk about [your] war responsibility,” the chamberlain told the emperor. “Given how the country has developed today from postwar rebuilding, it is only a page in history. You do not have to worry.”

—

See the Dec. 8, 2021, edition of Milestones for more on Hirohito.

Advertisement