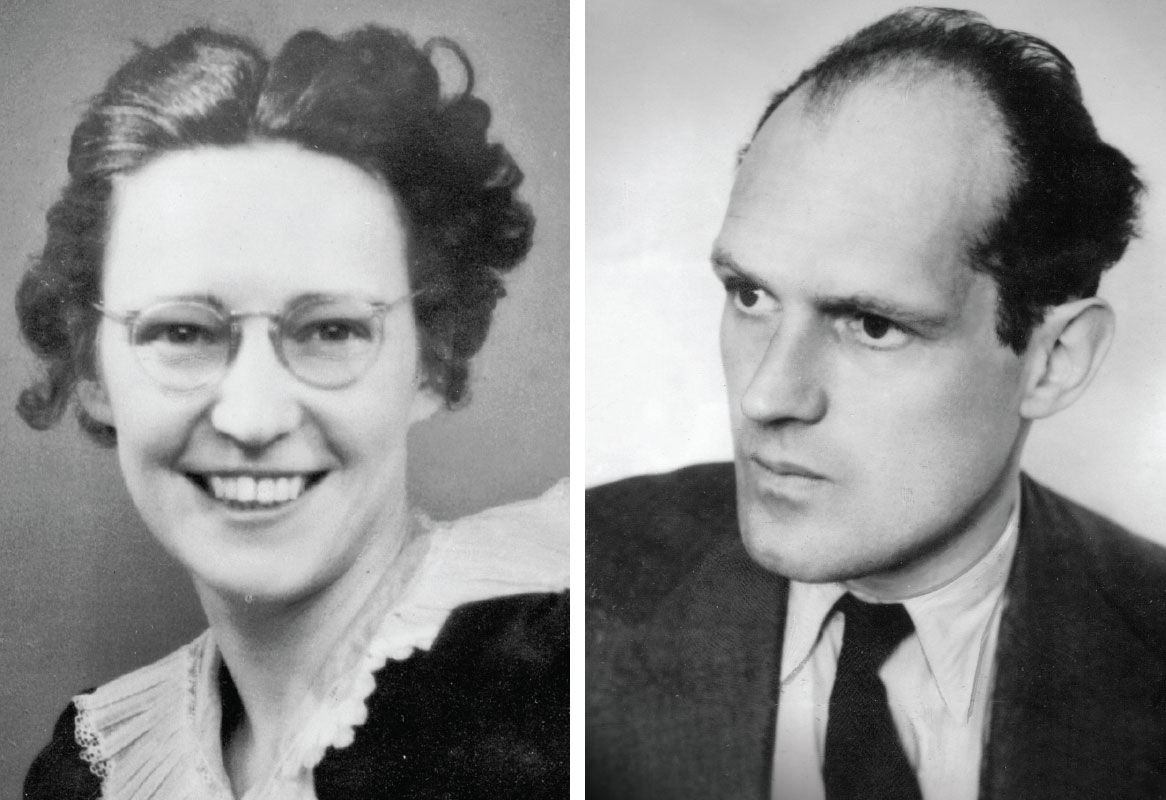

ELIZABETH (ELSIE) MacGILL

In 1939, Britain and the Commonwealth lacked a fighter plane to match the German Bf-109. In aerial combat over northwestern Europe in 1940, the 109, created by German aircraft designer Wilhelm (Willy) Messerschmitt, easily outfought existing Royal Air Force fighters.

In its pursuit of a competitive fighter plane, the RAF sent thousands of Hawker Hurricane blueprints on microfilm to the Canadian Car and Foundry Company in Fort William, Ont. (now Thunder Bay). Transforming the blueprints into a functional fighter and creating an aircraft assembly line fell to 35-year-old Elizabeth (Elsie) MacGill. In 1938, MacGill had been the first woman admitted to the Engineering Institute of Canada. Joining CanCar that same year, she oversaw the company’s conversion to aircraft manufacturing.

Each Hurricane required 60,000 perfectly manufactured parts, and MacGill pioneered a unique modular construction system inspired by Meccano sets. Ensuring every Hurricane perfectly matched the rest meant parts from one could be used to repair another.

MacGill oversaw the training and production work of a skilled workforce she created. Half of the 4,500 workers were women. By 1943, more than 1,400 Hurricanes had been produced.

“War effort,” MacGill reflected, “is a man staying and working an extra hour, or two or five hours a day…a woman cutting short her noon hour to finish the job…. War effort is something which is as microscopic in the unit as the individual, but as mighty in the sum total as an army.”

The first 40 Hurricanes off the production line were deployed during the Battle of Britain. By battle’s end, 1,715 Hurricanes had seen combat—accounting for 1,593 of RAF and RCAF’s total 2,739 kills. Although unable to match the Bf-109’s manoeuverability and speed, the Hurricane had a tighter turning arc. This gave the Hurricane an edge in dogfights.

MacGill also invented modifications to fit them with skis and created a de-icing system—developments crucial to their use by the Russians. Dubbed “Queen of the Hurricanes,” MacGill’s rise as a woman within the aeronautical industry resulted in U.S.-based True Comics profiling her achievements in a special 1942 issue.

By 1943, however, new fighter designs outpaced the Hurricane and production ceased. Stepping in, the U.S. navy contracted CanCar to build its Curtiss SB2C Helldiver. When continuous specification changes caused a production bottleneck, naval officials blamed MacGill and line-production manager Bill Soulsby. Both were fired. It later emerged that CanCar may also have fired them for having an affair. The two married, moved to Toronto, and enjoyed successful postwar careers. MacGill died in 1980.

“Although I never learned to fly myself, I accompanied the pilots on all test flights—even the dangerous first flight—of any aircraft I worked on.” – ELIZABETH (ELSIE) MacGILL “You can have any combination of features the Air Ministry desires, so long as you do not also require that the resulting airplane fly.” – WILHELM (WILLY) MESSERSCHMITT

WILHELM (WILLY) MESSERSCHMITT

When Germany’s Air Ministry issued a 1935 call for a new fighter design, aeronautical engineer and designer Wilhelm (Willy) Messerschmitt was advised not to compete again because his previous work in the field “was of no importance.” Undeterred, the maverick entrepreneur, who had built his reputation on producing light, fast aircraft, remarked: “You can have any combination of features the Air Ministry desires, so long as you do not also require that the resulting airplane fly.”

Ignoring proposed specifications, Messerschmitt produced his own design. The resulting Bf-109 won the single-seat fighter and multi-purpose fighter contests. Small, sleek, well-armed and very fast for the era, the 109 debuted at the 1936 Berlin Olympics. The Condor Legion, a unit made up of personnel from Nazi Germany’s air force and army, flew it in support of Franco during the Spanish Civil War. It easily overwhelmed the Russian fighters aiding the Republicans.

By the time Germany invaded Poland, the Bf-109 had been nicknamed the Messerschmitt or Me-109. Most Allied flyers called it this throughout the war. Each 109 could be built in 4,000 to 6,000 hours—faster than either the Hawker Hurricane or Supermarine Spitfire.

In the Battle of Britain, the Messerschmitt was a fair match against the Hurricane and Spitfire. This was primarily due to its manoeuverability. The 109’s limited fuel capacity, however, meant it could stay over England for only 30 minutes before returning to base. Reduced time-over-target combined with an ammunition load of only 1,000 rounds for each of its two engine-cowl guns tilted the balance against the Luftwaffe.

The 109 saw service throughout the war, however, because Messerschmitt regularly varied its design to improve performance and enhance firepower. Ultimately, 35,000 were produced—ensuring Messerschmitt’s legacy was tied to the fighter and its vital contribution to Germany’s air power.

Messerschmitt, however, also produced the world’s first operational jet—the Me-262. With Germany facing serious manpower shortages, he resorted to using slave labour at Gusen II concentration camp. Only about 300 of 1,443 jets produced saw combat—a number too small to influence the war’s outcome. And by war’s end, only a few hundred 109s remained operational.

Use of slaves—between 8,000 and 10,000 died—resulted in Messerschmitt’s conviction by a denazification court and a prison sentence. Released after two years, he returned to business. Germany was forbidden from producing fighter aircraft, but Messerschmitt designed the HA-100 for Spain. This plane’s final variant—the HA-300—was ultimately sold to Egypt.

Retiring in 1970, Messerschmitt died in 1978 at age 80.

Advertisement