“Sophie, Sophie, don’t die, stay alive for our children!” —Archduke Franz Ferdinand [Alamy/HRFP4D]

Down there, they will throw bombs at us,” Archduke Franz Ferdinand joked as he set out from Vienna, Austria, to the Bosnian capital, Sarajevo. As inspector general of Austria-Hungary’s armed forces, Ferdinand ostensibly travelled to observe army manoeuvres but also to showcase his wife publicly in a quasi-royal role. Sophie Chotek’s lack of direct lineage to a European dynasty technically rendered her ineligible to marry into the Imperial House of Habsburg. Thoroughly besotted, however, Ferdinand had wrangled Emperor Franz Joseph’s permission to marry her in 1900. But Sophie was denied royal status and prohibited from appearing publicly alongside the archduke.

Ferdinand’s marrying outside of convention reflected his headstrong temperament. Born in 1863, a series of deaths within the Habsburg family made him heir-apparent to the throne in 1896. He quickly established a reputation as short-tempered, prideful and mistrusting. These attributes, combined with a lack of charisma, made him generally unpopular, as did his intention, on attaining the throne, to give the empire’s Slavic population an equal voice in government alongside the German and Magyar elites.

Ironically, this plan to accommodate the empire’s Slavs led radical nationalists with links to the Serbian government to target Ferdinand for assassination. They feared such policies would quell Slavic unrest and dash dreams for a Greater Serbia.

Against this backdrop, a six-car motorcade set out in Sarajevo on June 28 with Ferdinand and Sophie riding in the open-topped second car. The route following the river to city hall had been well publicized. Mingled into the assembled throngs were six young assassins, one of whom threw a bomb that exploded next to the third vehicle. Several officers were injured and a small splinter cut Sophie’s cheek. The assailant was quickly arrested.

“Come on, that fellow is clearly insane, let us proceed with our program,” Ferdinand said. Arriving at city hall, Ferdinand lashed out at Sarajevo’s mayor. “I come here as your guest and you people greet me with bombs!” he shouted. The cheering crowd and mayor’s conciliatory speech, however, mollified Ferdinand. A more direct route was agreed on for the return trip, but the motorcade drivers were not informed. When the lead car turned according to the original plan, the second followed before halting to turn around. This was Gavrilo Princip’s opportunity. He fired two point-blank shots. Sophie was hit in the abdomen, Ferdinand in the neck. “Sophie, Sophie, don’t die,” Ferdinand implored. But both wounds were fatal.

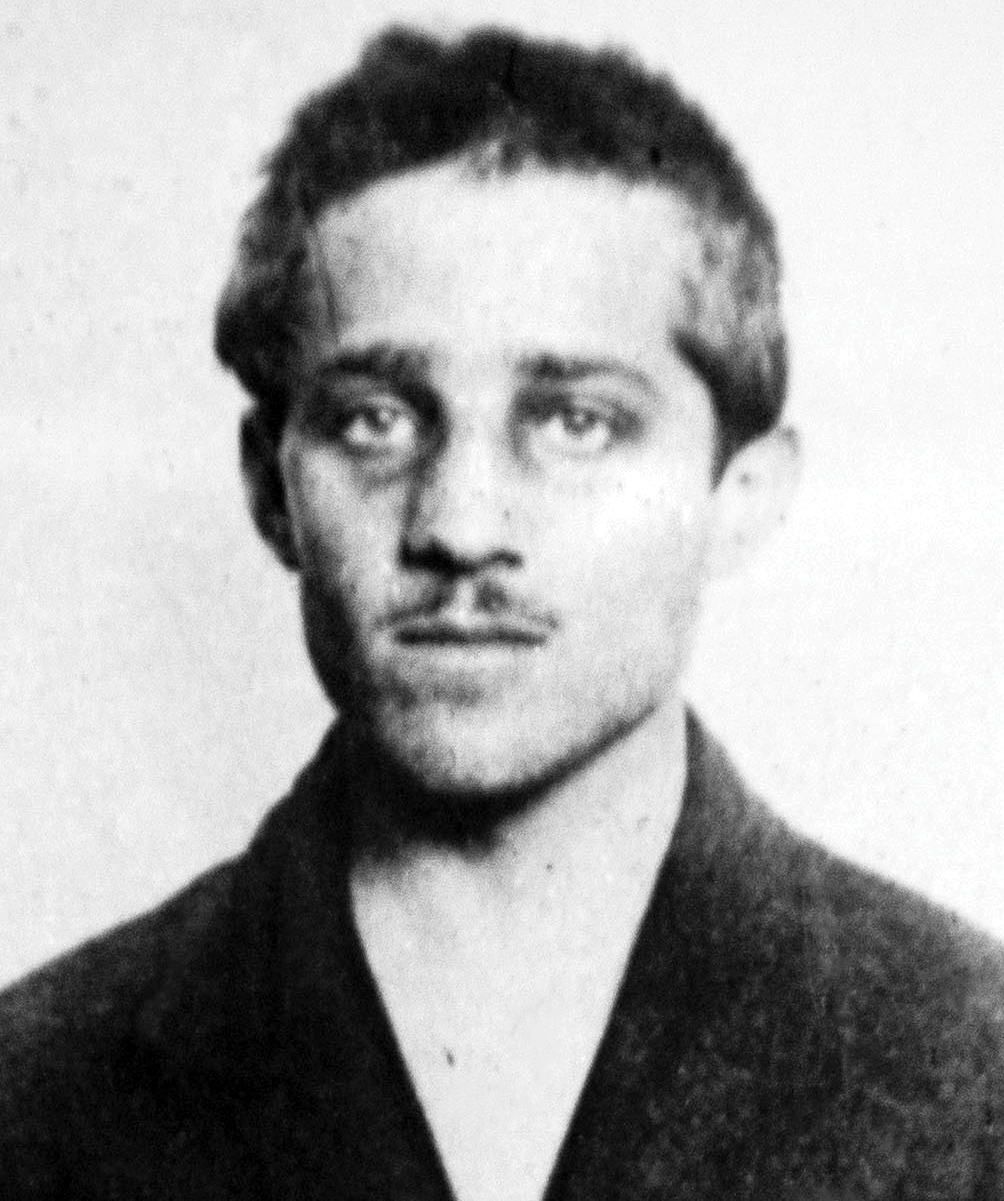

“I do not care what form of state, but it must be free from Austria.” —Gavrilo Princip [Wikimedia]

Gavrilo Princip was one of many young Bosnians inspired by Bogdan Žerajić, a 22-year-old student who killed himself after a failed 1910 assassination attempt on Herzegovina’s governor. Žerajić’s Sarajevo grave became a radical shrine. “I often spent whole nights there thinking about our situation, about our miserable conditions,” Princip said during his trial. It was there “that I resolved to carry out the assassination” of Archduke Franz Ferdinand.

Princip was an ethnic Serb born in 1894 to impoverished parents in remote western Bosnia. In 1907, he moved to Sarajevo to get a secondary education. Here he met young radicals opposed to Austro-Hungarian rule. Grades falling and truancy rate rising, he was expelled in 1912. Moving to Belgrade, Princip volunteered to join Serbian guerillas fighting Ottoman Turks, but was rejected as unfit.

In Belgrade, Princip came into contact with members of the Black Hand—a secret Serb nationalist group with covert government ties that sought to create a Greater Serbia which would absorb the Bosnian Croats and Muslims. Princip rejected this agenda. “I am a Yugoslav nationalist, aiming for the unification of all Yugoslavs, and I do not care what form of state, but it must be free from Austria,” he declared.

The Black Hand provided Princip and two accomplices with four Browning pistols, six small bombs and cyanide powder to take their own lives after the deed was done. The organization smuggled them into Bosnia at the end of May. In Sarajevo, they met a Black Hand cell whose leader provided three more recruits. The oldest of the six would-be assassins was 28, the youngest, 17. Princip and two others were 19.

On Sunday, June 28, they scattered among the thousands gathered to welcome Ferdinand and his wife to Sarajevo and prepared to individually attack the motorcade. The first team member panicked and fled, while 19-year-old Nedeljko Čabrinović’s bomb missed Ferdinand’s car. When the motorcade route was changed, the remaining members were left out of position, except for Princip who happened to be at an intersection when the first two vehicles stopped to turn around. Princip ran forward and fired his two fateful shots. As he tried to shoot himself, members of the crowd knocked both weapon and cyanide from his hands.

Being under 20, Princip was spared the death penalty and instead sentenced to 20 years. He succumbed to skeletal tuberculosis in a prison hospital on April 28, 1918.

Advertisement