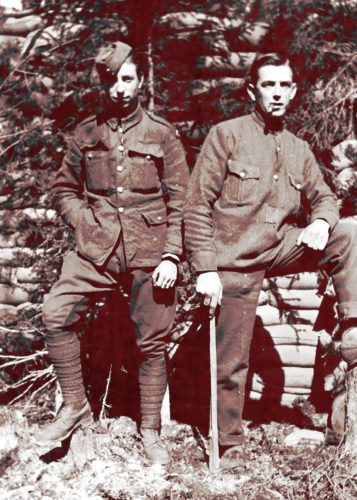

Two Canadian gunners pose with transport sled drivers in Russia in February 1919. [Alan A. Outram/LAC/PA-037374]

As the war on the Western Front ended, the Allies took on the Red Army on its own turf

It was all Winston Churchill’s fault.

In 1918, he was Minister of Munitions in Prime Minister Lloyd George’s Liberal government. In 1919, he became Secretary of State for War. During this period, he was determined to smash the Marxist Bolshevik government in Russia.

He pressed for Allied troops to be used to support the “Whites” (anti-communist forces) against Vladimir Lenin’s Red Army, which was directed by the energetic, innovative Leon Trotsky.

British troops had first been sent to northern Russia in March 1918 to help keep the country in the war and to safeguard Allied supplies stockpiled at Archangel and Murmansk. German troops in Finland, some feared, might seize them after the Bolshevik surrender signalled by the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk that month.

In early June, with Churchill’s urging, the Supreme War Council agreed that the small British force, initially a training mission which included a few Canadians, should be expanded into a 35,000-man multinational Allied and White Russian force. Soon American, French, Italian and Serbian troops were dispatched to northern Russia. On Oct. 1, two batteries of the 16th Brigade, Canadian Field Artillery, arrived with 22 officers and 475 other ranks—most of them veterans of the fighting on the Western Front.

Gunner W.G.T. Wenn (holding stick) and his unidentified comrade served with the Canadian Field Artillery in northern Russia in 1919. [PA-037383]

The situation was chaotic when the Canadian gunners landed at the White Sea port of Archangel. The Allied forces had advanced on five widely separated fronts, some almost 500 kilometres from their base at Archangel. The Russian populace seemed not much interested in resisting the Bolsheviks and communications and co-ordination were all but impossible over the swamps of the region.

The new Allied force commander, Major-General William Edmund Ironside, altered command arrangements and had his troops set themselves up for defence as the bitter winter darkness closed in. Conditions were extremely difficult for the men.

The Canadians found themselves fighting for their lives.

“Woollen gloves with a separate compartment for the trigger finger were essential,” wrote Ironside. “When the fingers became numbed there were gauntlets strung round the soldier’s neck into which they could be thrust until the circulation came back. To touch metal with the bare hand was like grasping a piece of red-hot iron.”

Ironside had been a senior staff officer with the 4th Canadian Division in France since 1916. He understood Canadian soldiers well, and he relied heavily on the two artillery batteries. They did not let him down.

The gunners were quickly deployed to the banks of the Northern Dvina River at the village of Tulgas 350 kilometres southeast of Archangel, in support of the American 339th Infantry Regiment, a green unit, and a small British battalion of low medical category men from the Royal Scots.

A section of two guns from the 67th Battery faced a large Bolshevik force. After softening up the Allied positions with fire from gunboats and artillery that easily outranged the Canadian 18-pounders, the Bolos, as the Yanks called them, attacked in force on Nov. 11, 1918, ironically the day the Armistice came into effect on the Western Front. The Canadians found themselves fighting for their lives.

To the north of the village, 600 Reds attacked through the woods and fell on the rear of the Canadian gun positions. A dozen Canadian drivers and signallers who had believed themselves behind the lines realized they were under attack when the enemy was only 200 metres away. Holding off the attackers with rifle fire, they retreated to the two 18-pounders in their gun pits. One gun was quickly swung around to face the advancing enemy, firing over open sights at point-blank range. A platoon of Royal Scots joined the defenders, who wreaked havoc on the Reds and held their ground.

As darkness fell, the second 18-pounder was swung round and the enemy retreated, leaving at least 60 dead and wounded behind. Two Canadian gunners and 10 Royal Scots were killed in this engagement.

The Red Army was demonstrating that its spirit was high.

Fighting continued for four more days before the enemy retreated, leaving Tulgas in Allied hands.

The guns had saved the day, and praise and gallantry decorations were lavished on the Canadians. “The Canadian artillery, by the action of its drivers and gunners, had worthily upheld the traditions of British gunners,” said Ironside.

The Canadians of the 67th Battery then settled in for the winter at Tulgas, bolstering their defences. In January, a section of 4.5-inch howitzers and two 60-pounders finally gave the gunners artillery that could match the range of the Bolshevik guns.

Canadian gunners stand ready with a 60-pound heavy field gun in northern Russia in May 1919. [Alan A. Outram/LAC/3405794]

Meanwhile, the 68th Battery was on the Yemtsa River, where on Dec. 30, its guns supported an American and French attack on Kadish, a village on a river crossing. A major Bolshevik counterattack on New Year’s Eve was driven off, the guns being instrumental in the successful defence.

“During this fight, or rather after it, the Canadians taught our boys their first lesson in looting the persons of the dead,” one American noted. “Our men had been rather respectful and gentle with the Bolo dead who were quite numerous…. But the Canadians, veterans of four years fighting, immediately went through the pockets of the dead for roubles and knives and so forth and even took the boots off the dead, as they were pretty fair boots.”

By January, however, the Red Army was demonstrating that its spirit was high, its fighting skills improving as reforms implemented by Trotsky took hold. (He was rumoured to be personally in command of the northern Russian front). A general offensive to drive the Allies out of Archangel began and in mid-January, American troops and Canadian gunners were driven out of Shenkursk. A gruelling retreat down the Vaga River ensued, during which Captain Oliver Mowat, commanding the guns, was killed.

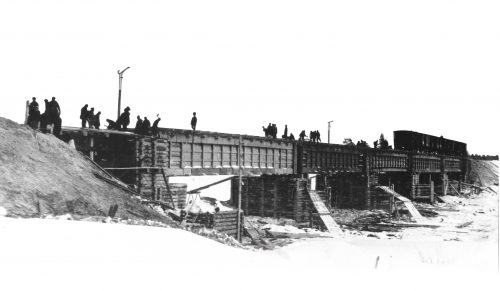

Russian construction workers finish a railway bridge (top) over a river near Murmansk in 1919. [DND/LAC/3397661]

The Allied operations had some air support, but this was not without problems. The water-cooled engines on Airco DH-4 bombers froze in the Russian winter, and initially there were too few French-built Sopwith Strutters with air-cooled engines.

But the air force component—some 18 of its pilots and observers were Canadians serving in the Royal Air Force—were inventive, flying their Sopwith Baby seaplanes from rivers and rigging aircraft with handmade skis to land and take off from snow-covered fields. The aviators fought few air-to-air combats, but they strafed, bombed, mapped and flew reconnaissance flights. Some Canadians built fine reputations. Captain Dugald MacDougall from Lockport, Man., for example, was hailed as an “indefatigable pilot” who did valiant work flying his seaplane from the Northern Dvina River until he was killed in an explosion in August 1919. He was awarded a posthumous Distinguished Flying Cross.

British Major-General William Edmund Ironside (front right) commanded the Allied intervention force in northern Russia in 1919. General Sir Henry Rawlinson (front left) commanded the evacuation. [DRHF2T/Chronicle/Alamy]

Nonetheless, by early 1919 Allied morale was flagging. The war against Germany was over, and American and Canadian troops were beginning to return to North America from France, Belgium and Britain.

Those in northern Russia, however, remained on the ground, fighting a war in grinding conditions without readily understandable aims. The Bolshevik propaganda was insidious, sapping morale, and the White Russians were generally untrustworthy. Some of the Russians mutinied, killing their officers.

Soon, British, French and American units became restive, and minor mutinies erupted, men briefly refusing to move to the front. The Canadian gunners grumbled, but continued to perform their duties. “The Canadians out here, especially the artillery brigade, have been the backbone of the expedition,” said Ironside in April.

“The Canadians out here…have been the backbone of the expedition.”

The fighting continued. At Tulgas in May, the defenders were forced out, but when the river ice finally cleared, British gunboats and efforts on land by the 67th Battery and infantry led to Tulgas being recaptured.

But Allied leaders were becoming increasingly uncertain about the value of the anti-Bolshevik campaign, and Prime Minister Robert Borden, initially a supporter of the effort to topple Lenin’s regime, changed his tune.

A Canadian gunner (seated) supervises prisoners as they unload a barge in May 1919. [Alan A. Outram/LAC/PA-037404]

As early as January 1919, he had concluded there was little to gain by having Canadians fighting in Russia, a position with which public opinion in Canada increasingly agreed. The British argued that nothing could be done until the ice on the rivers broke up. But in May, after two additional demands for the withdrawal of his soldiers had been rejected, Borden insisted that the Canadians be relieved at once. This time, the War Office agreed.

By early June, the two batteries of the 16th Brigade were back in Archangel. They had lost eight men killed and 16 wounded. The White Russians decorated several officers and men for their service. After reviewing the Canadians at their final parade at Archangel, Ironside declared that “over and over again, the Canadian Field Artillery had saved the force from destruction.” On June 18, the 16th Brigade landed in Scotland.

By October 1919, all the Allied forces in northern Russia had withdrawn. The Red Army occupied Murmansk and Archangel soon after. The intervention against the Bolsheviks in northern Russia, a campaign now all but forgotten, was a failure.

Advertisement