Canadians, many born in the British Isles, descended on recruiting stations in Toronto, Kingston, Ont., Valcartier, Que., and elsewhere between 1914 and 1916, driven by the call to defend king and country in lands far away.

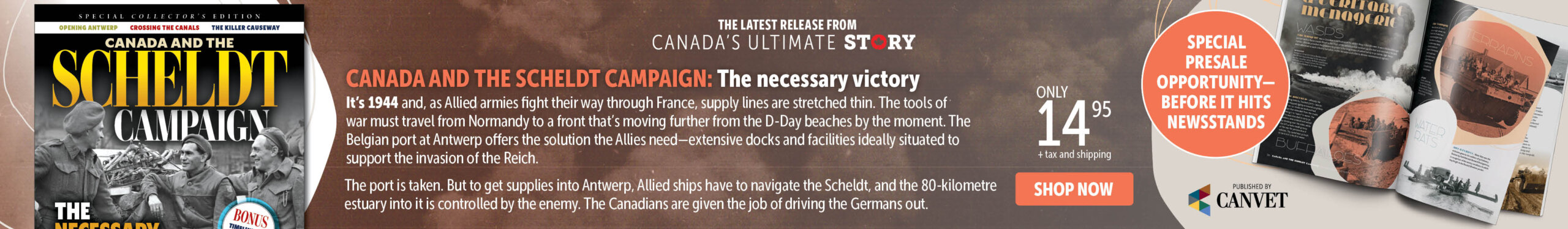

They were bricklayers and electricians, clerks and painters, office workers and locomotive engineers. Most were young recruits, just out of school and living in west-end Toronto. Arthur William Rawlinson was 35. Sydney Raven was 16. All were photographed before they went off to fight. A memento for loved ones.

Rendered on glass plates in faded sepia, their faces reflect a range of pre-combat attitudes and emotions—innocence, confidence, anticipation, apprehension—the grim realities of the new, industrialized warfare yet to be realized.

Almost a third didn’t return. More than a third survived debilitating wounds and poison gas. Miraculously by the standards of the day, just over a third made it home physically unscathed.

Some of the photographs have the address of a photo studio once located next to the Elgin and Winter Garden Theatre on Yonge Street in Toronto. They were discovered in the estate of Bob French, a retired corporal of The Queen’s Own Rifles, and consigned to Juan José Besteiro, president of the Canadian Society of Military Medals & Insignia.

Short profiles of eight of the men are included with their photos in the following pages.

When he signed up in March 1916, his complexion was described as “fresh” in his attestation documents.

Sydney Vernon Raven of Toronto was just 16 years old when he signed up in March 1916, his complexion described as “fresh” in his attestation documents. His 22-year-old brother, Frank Leonard Raven, had joined in January and served as a driver with No. 35 Field Ambulance before he was sent home in December 1917 with trench fever—a highly contagious, lice-borne disease marked by high fevers, severe headaches and soreness of the legs and back. Pte. Sydney joined the 12th Brigade, Canadian Field Artillery headquarters in England as a driver a few months after he signed up. Less than a year later, he landed in France with the 5th Canadian Divisional Ammunition Column. He was granted permission to marry an English girl, Lillian, in December and given 14 days’ special leave to do so. He served out the war and returned to Canada with his bride in June 1919.

Born in Liverpool, England, Private Arthur William Rawlinson was 35 years old when he enlisted at a Toronto recruiting station in September 1915. He was just five-foot-four, 123 pounds. After sailing out of Halifax with the 74th Battalion aboard the Empress of Britain in March 1916, Rawlinson was reassigned to the 1st Battalion, Canadian Mounted Rifles, after it was overrun in a German attack and suffered 80 per cent casualties at Mount Sorrel. Rawlinson was wounded on Sept. 15, 1916, as his battalion joined the first wave attacking Mouquet Farm on the Somme. He was back in the line five days later, only to be killed in action on Sept. 30. He was 36.

Frank Shrubshall was born in Faversham, England, in 1881 and became a locomotive engineer with the Canadian Pacific Railway before he enlisted at age 34 in Toronto in March 1916. As a member of the 38th (Ottawa) Battalion, he received a field promotion to sergeant in October 1917 and was, according to his records, “killed instantly by a machine gun bullet during the advance on the Drocourt-Quéant Line on the morning of September 2, 1918.” He was awarded a posthumous Distinguished Conduct Medal, the second-highest award for valour, almost five months later. He left behind a wife, Edith, and two children.

Sergeant Bertram John Topham, a native of Northwich, England, was an electrician before he signed up for military service at Valcartier, Que., shortly after the war began in September 1914. He was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal for his actions with 3 Company, 14th Battalion (Royal Montreal Regiment), at Mount Sorrel on June 3, 1916. According to a unit history, Topham led a party of 14 men and established contact with the enemy at a point on the Allies’ left flank. “When his advance was checked, Topham took up a position and for the whole day defied the enemy’s efforts to eject him,” it said. “Casualties he could not avoid; and gradually his little party dwindled. At night, together with some two or three survivors, he retired on the main body of the Battalion.” His medal was awarded by none other than Lieutenant-General Julian Byng a month later. Topham fought through France and Belgium. He was concussed and suffered lifelong hearing loss from an exploding shell before the war ended. He died in 1962 in Toronto, age 67.

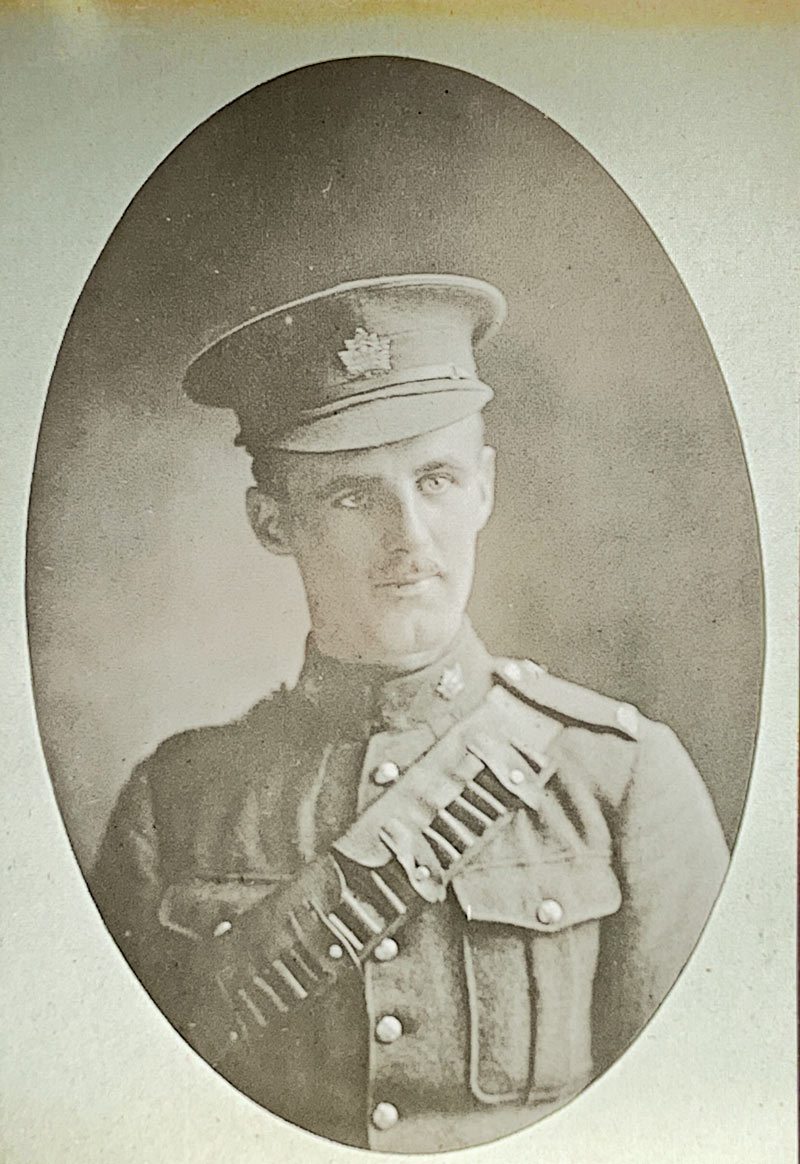

Toronto native Frederick Swebert Kirkwood, a clerk, signed up at Kingston, Ont., in September 1916 and served as a driver with ‘C’ Battery, the Royal Canadian Horse Artillery, for 16 months before he was shot in the thigh at Amiens, France, during the German spring offensive of April 1918. His leg was amputated well above the knee, leaving just a 25-centimetre stump. Twenty-two at the time, he would spend a year in hospitals in France, England and Canada. He endured several operations and would suffer phantom foot pain in wet weather for the rest of his life. He returned to Toronto, resumed work as a clerk, and married Ruby Alexandria Whillier, a 21-year-old stenographer from England, in 1925.

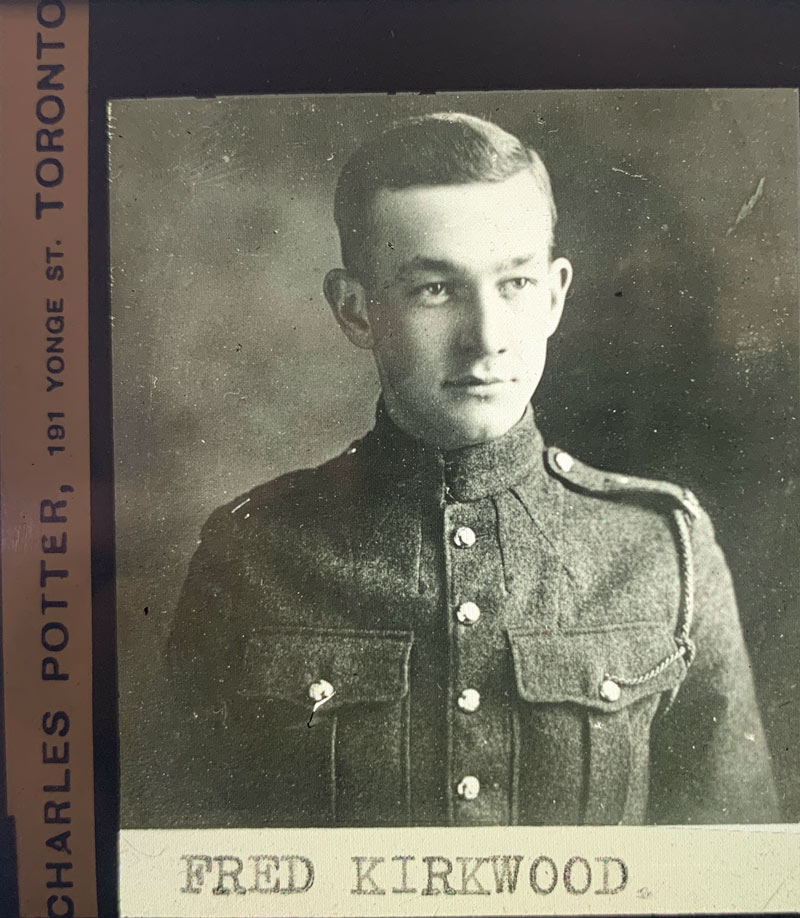

Born in Toronto, George Peter Mallaby was a gunner with the 21st Battery, Canadian Field Artillery, when he was gassed at Passchendaele, Belgium, on Nov. 1, 1917. Artillery shells and heavy rains had turned the battlefield into a wasteland of mud, swamp and water-filled craters. Canadian units took 15,000 casualties, including more than 3,000 men confirmed killed and 1,000 more missing and presumed dead, many of them lost in the mud. Mallaby, a Woolworth employee before signing up at age 21 in March 1916, was back in circulation within a month and survived the war.

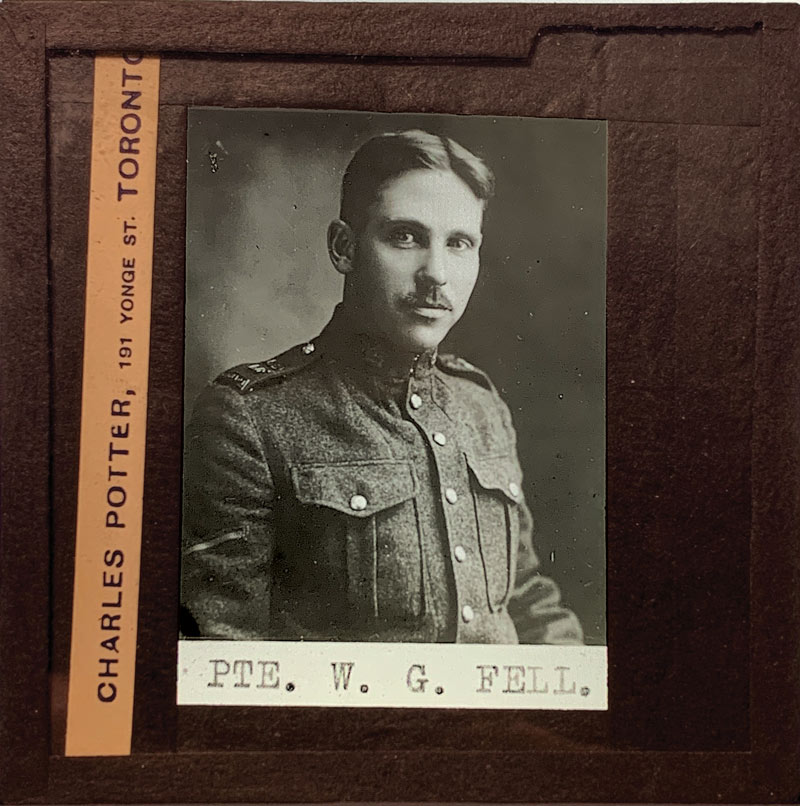

William George Fell went missing in action around Ypres on Sept. 30, 1917. He was officially declared killed in action in April 1918.

Montreal-born William George Fell was a 32-year-old master painter and decorator when he signed up in Toronto in March 1916. A lance-sergeant in the 116th (Ontario County) Battalion, he was wounded on a raid north of Avion in July 1917, then went missing in action around Ypres on Sept. 30. He was officially declared killed in action in April 1918; his remains were never found. His name is on the Canadian National Vimy Memorial on Hill 145 north of Arras, among 11,285 Canadian soldiers listed who were declared missing and presumed dead in WW I France.

Advertisement