![CoppLead A tank crew prepares for battle. [PHOTO: KEN BELL, LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA—PA162390]](https://legionmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/CoppLead.jpg)

Operation Spring, 2nd Canadian Corps’ second attempt to secure Verrières Ridge, began in the dark during the early hours of July 25, 1944.

Although Lieutenant-General Guy Simonds commanded two infantry and two armoured divisions and a full armoured brigade, the first phase of the attack involved just three infantry battalions. These battalions were to secure the villages of May-sur-Orne, Verrières and Tilly-la-Campagne, setting the stage for the infantry-armour battle groups that would advance at first light.

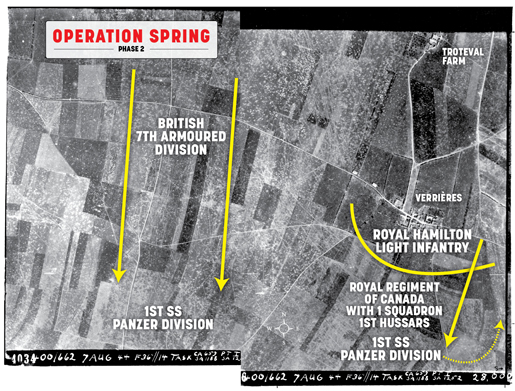

All three Phase I battalions—the Calgary Highlanders, Royal Hamilton Light Infantry (RHLI), and the North Nova Scotia Regiment (Highlanders)—reported reaching their objectives. Reaching, however, did not mean controlling the objectives, and so when Simonds met with his divisional commanders at 7 a.m. that morning he had to decide if early reports of progress were sufficient grounds to begin the second phase of the operation. Simonds did not hesitate. He ordered 7th Armoured Division to advance across the ridge to the west of Verrières village while the Royal Regiment of Canada and a squadron of First Hussars tanks looped around the village to the east. These attacks, he believed, would lend support to the North Novas who were under severe pressure at Tilly-la-Campagne, and the Black Watch which was re-organizing before beginning its advance.

The Black Watch possessed a strong reputation based on its First World War tradition and solid performance in the more recent Operation Atlantic. When the battalion reached its forming-up place at St. Martin, it came under heavy fire from enemy machine-gun posts which struck the command group, killing Lieutenant-Colonel S.S.T. Cantlie and wounding two of his company commanders.

The story of the Black Watch advance over the crest of the ridge has been told many times. The battalions’ casualties—123 killed, 101 wounded, and 83 taken prisoner, all in the space of a few hours—prompted questions in Parliament and an official inquiry.

The gamble that failed was the decision by the senior surviving company commander, Major F.P. Griffin, to bypass May-sur-Orne in the hope that the Calgary Highlanders would complete the capture of the village. Instead, the battalion ran into a ferocious counterattack by an armoured battle group of 2nd Panzer Div. which overran the Black Watch and destroyed the First Hussars squadron supporting the infantry. Focusing on the disaster that overwhelmed the Black Watch has drawn attention away from the battles fought by 4th Brigade in the centre of Verrières Ridge. This approach to covering the history of the operation was evident as early as 1948 when historian C.P. Stacey’s first official overview of the war appeared in the book, The Canadian Army, 1939-1945.

Brig. John M. “Rocky” Rockingham, who commanded the RHLI in its successful advance to secure Verrières village, wrote to Stacey to point out the curious decision to provide “considerable space (within the book)…to the unsuccessful attacks of other units engaged in the battle but only three lines to the RHLI…” Rockingham was particularity upset with a further comment that “the tanks of 7th Armoured. Division and RAF Typhoons are credited with breaking up a formidable counterattack and probably saving Verrières.”

Rockingham told Stacey that “counterattacks [on the RHLI] began almost immediately, causing further casualties to troops and equipment…As for the counterattack in the evening, by the time the tanks of 7th Armoured Division had arrived, battalion weapons and the artillery had stopped the enemy.” As for the Typhoons, “one round of red smoke…fell short and landed on my headquarters and caused three Typhoons to fire their rockets on us.” When the Victory Campaign (the official history of the Canadian Army in the Second World War) was published in 1960, Stacey provided a more balanced account of Operation Spring. But it still focused on the Black Watch. The 4th Bde. story is equally compelling.

![CoppInset1 A soldier waits for the artillery barrage to clear before moving forward. [PHOTO: KEN BELL, LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA—PA163403]](https://legionmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/CoppInset1.jpg)

During battlefield study tours, it is important to engage participants in active learning on the ground in Normandy. Students participating in the tours I am associated with are required to plan the RHLI advance from Troteval Farm to Verrières village using 1944 maps and the air photos that were available to Rockingham. The real challenge is to defend the village against counterattacks. Students have to decide on the location of DF (Defensive Fire) zones and assign tasks to the supporting arms, especially the anti-tank guns of 2nd Anti-Tank Regt., Royal Canadian Artillery.

We then walk the kilometre from the start line to the village and discover just how different the actual ground is. The 1:25,000 map used for planning in 1944 turns out to be of little value. Verrières village is not on the ridge as the map indicated, but nestled well below the crest. This offers the opportunity to defend the village just as Rockingham did using the 17-pounder anti-tank guns to counter enemy approaches on the open flanks and the battalion’s six-pounders to destroy panzers as they came over the top of the ridge. Verrières village is a superb, reverse-slope defensive position and the RHLI had the skill and discipline to make the best use of it.

The ferocity of the day-long battle to hold the village causes students to question Simonds’ decision to order the Royal Regiment of Canada with a squadron of First Hussars’ tanks to bypass the village and attempt to reach Rocquancourt. We first ask them to consider the timing of the order, before the first counterattack occurred. Next, the parallel advance of 7th Armd. Division’s battalions on the west side of the village suggests a large-scale operation that might overwhelm the enemy. But then, Simonds’ own words must be considered. In his directive to the corps he wrote: “The success of the offensive battle hinges on the defeat of the German counterattacks with sufficient use of our own reserves in hand to launch a new phase as soon as the enemy strength has spent itself.”

The decision to send “our own reserves” forward before the extent of the enemy response was known clearly violated the corps commander’s own doctrine, making his decision difficult to defend.

The students and I then walk from the churchyard, with its memorial to the RHLI, up a farmer’s lane to the top of the ridge. A fence of bushes and small trees line the lane, but this is not hedgerow country and there appears not to have been any tank obstacles anywhere on the ridge. To the west an expert eye can point out Hill 88, the highest point of the ridge and the regular lines of the planted forest leading to the Black Watch objective, Fontenay-Le-Marmion. Point 77, referred to in the war diaries of 7th Armd. Div., is 400 metres west on the northern edge of the ridge. This is the furthest point reached by the British tank squadrons.

When Simonds had outlined his plan for Operation Spring, both British divisional commanders still in shock from the heavy tank losses suffered in Operation Goodwood, were reluctant participants. Their corps commander, Lt.-Gen. Sir Richard O’Connor, had urged them to “go cautiously with your armour, making sure any areas from which you could be shot up by Panthers and 88s are engaged…remember you are not doing a rush to Paris.”

Major-General George Erskine, the veteran commander of 7th Armd. Div., needed no such warning. He was openly critical of plans to throw his thinly armoured and under-gunned tanks at the heaviest concentration of enemy armoured forces ever assembled. The squadrons of the 1st Royal Tank Regt. that reached the crest of the ridge on July 25 were “shot up by Panthers and 88s” and reported that at least 30 German tanks or anti-tank guns were positioned to crush their advance. Survival meant withdrawing below the crest and taking up a reverse slope position.

Today, the Royal Regt. of Canada/First Hussars battlefield is clearly visible to the east of the farmer’s lane in the wheat fields.Back then there was no cover of any kind. To advance onto the ridge in daylight was to invite disaster. The Royals war diary reported the result: “Companies…were immediately attacked by heavy fire from 88-mm, mortars, and medium machine guns. When C Company continued its advance it was able to get over the ridge with heavy casualties and the large part of the company with its remaining officer were either prisoners of war or wiped out. C Company came out of the battle [with] 18 other ranks only.”

The Hussars lost 15 of the 18 Shermans committed to the action. By late afternoon the Royals and a troop of tanks were dug in to the east of Verrières village. The Royals had been up to strength the morning of July 25, but after the battle they required 254 riflemen replacements.

The situation at Tilly-la-Campagne was equally desperate. By 8 a.m., Lt.-Col. Charles Petch had radio contact with just one of his four companies and could use the artillery only on targets distant from areas where the men might be. A number of them crawled like “snakes on the ground” back through the wheat with reports of dug-in tanks, machine-gun posts and camouflaged strongpoints. The divisional commander, Maj.-Gen. Rod Keller waited until midmorning before ordering Brigadier D.G. Cunningham, commanding 9th Bde., to use his reserve battalion, the Stormont Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders, to assist the North Novas in Tilly. The warning order reached the Glens at 11:25 a.m. Lieutenant Reg Dixon, the intelligence officer who kept the war diary, described the news as “a mental blow felt by all ranks.” Both officers and men were “looking worn out and very weary.” Dixon noted that “even Jerry with his lack of divisions and manpower has withdrawn divisions for rest and refit as had the British.” The battalions of 3rd Canadian Div. had not been out of contact with the enemy since D-Day.

Between 11:25 a.m. and 4 p.m. an extraordinary drama unfolded at 9th Bde. headquarters. The Glens’ commanding officer, Lt.-Col. G.H. Christiansen, went forward to the North Nova command post at Bourguebus to see the situation first hand. Cunningham was already there with Petch. The three men discussed the situation and Petch was unwilling to send his ad hoc reserve, made up of men who had made it back from Tilly, into the killing zone. Christiansen, meanwhile, flatly refused to order his battalion to undertake what he considered a hopeless action. Cunningham returned to his tactical headquarters and informed Keller there was no point reinforcing failure at Tilly. Keller had just come from a conference at corps headquarters where he was told to hold Tilly in preparation for a renewed offensive. Relations between the two men had been strained since the dispute over the “delayed” advance into Caen, and Keller told his brigadier that unless he obeyed it would cost him his job. Cunningham recalled saying to Keller that he understood that, but stuck to his position. At 4 p.m. the Glens were told to stand down. There would be no daylight attack on Tilly, but Cunningham, Christiansen and Petch all lost their jobs and were reassigned.

Operation Spring ended during the evening of the 25th as a revolt against Simonds’ orders spread. Brig. Young, whose 6th Bde. was suppose to capture Rocquancourt, concluded that further attacks were futile “until the west bank of the Orne had been cleared.” Until such a time, the enemy could keep hammering the area of the objective with intense mortar and artillery fire. Young went to divisional headquarters at 8 p.m. and informed General Charles Foulkes that any further attack “stood little chance of success.” Foulkes agreed and went to see the corps commander “to tell him that I had no intention to continue the battle as I had nothing left to fight with.”

The corps had suffered more than 1,500 casualties, about 450 of them fatal. Even the Rileys (RHLI), who had won the only great victory of the day, recorded 200 casualties, including 53 men killed in action. For the North Novas with 232 casualties and the Black Watch with 307, the second battle for Verrières Ridge meant that the combat elements of both battalions would have to be completely rebuilt before the next major operation.

Email the writer at: writer@legionmagazine.com

Email a letter to the editor at: letters@legionmagazine.com

Advertisement