PART II: SECOND WORLD WAR

Abused prisoners and great escapees

By Sharon Adams

The night before Canada declared war on Germany in 1939, Flying Officer Alfred B. Thompson of Penetanguishene, Ont., was co-pilot on a Royal Air Force mission to drop propaganda leaflets over communities in the Ruhr Valley in Germany. The plane was hit by anti-aircraft fire and the crew bailed out and was captured by farmers, who turned them over to the German military. Thompson became the first Canadian taken prisoner in the Second World War.

Air force prisoners were “still such a novelty that Thompson was personally greeted by high-ranking Nazi Hermann Göring before the Canadian was packed off to prison camp,” wrote David L. Bashow in No Prouder Place.

Goering talked about hockey, made an empty promise that the airmen would be treated well, and posed for publicity shots. Those pictures may have been lifesavers nearly five years later when nine Canadians, including Thompson, were among 76 Allied PoWs recaptured after The Great Escape from Stalag Luft III in what is now Poland. Contrary to the Geneva Conventions, Hitler ordered 50 killed; six Canadians were murdered, but Thompson was not among them.

Some PoWs captured by German military, particularly early on in the war, were treated humanely, but Canadians were starved, frequently beaten and sporadically murdered throughout the war.

First to be caught were flyboys. For most, it began a sentence of years of health-sapping hunger and mind-bending boredom, if not cruelty and life-threatening brutality.

At the beginning of the war, with Canadian soldiers cooling their heels waiting to get into the action, Canadian fighter pilots and bomber crew were disproportionately represented among prisoners of war. But by war’s end, the tally shifted: nearly 7,000 members of the army and 2,500 air force members had been taken prisoner in Europe and Asia. Fewer than 100 Royal Canadian Navy members became PoWs, thanks to the sailors’ perennial enemy, the sea, which swallowed most survivors of enemy action.

Canadian PoWs were but a drop in the ocean among upwards of 13 million soldiers, sailors and air crew estimated to have been captured around the world in the Second World War. Many were treated barbarically, despite eight decades of concerted international efforts to civilize treatment of military prisoners.

First World War PoWs were starved, ill-housed, severely punished, executed. The International Red Cross set out in 1921 to beef up the laws. The 1929 Geneva Convention Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War was ratified by most belligerents of the Second World War, save, notably, the Soviet Union and Japan. Some lived by the rules only when it suited them, and a few observed neither the word nor the spirit of the law.

The agreement stipulates that prisoners must be humanely treated and protected from violence. On capture, prisoners need only give their name and rank. Home countries must be promptly notified of the capture. (Civilians are covered under separate agreements.) PoWs are to receive the same standard of housing and food as their host country’s military. Restriction of food and beatings are unacceptable punishments. Escaped prisoners are not to be executed, but may be incarcerated for up to 30 days. Transfer to military or criminal prisons is also unacceptable punishment.

German PoWs in Canada and England fared best of all—so much so that some emigrated after the war (read “The Happiest Prisoners” to learn more about the treatment of German POWs in Canada). European countries generally lived up to the agreement, but on the Eastern Front, bad relations between Germany and the Soviet Union ensured mutually brutal treatment. And military prisoners of Japan, which considered surrender to be shameful, were used as slave labour, kept in unsanitary conditions, starved, beaten, tortured and murdered.

Protection from violence may have been the law, but surrender remained a dangerous event.

In 1943, Heinrich Himmler, commander of the Schutzstaffel (SS), decreed police should not intervene with civilian lynch mobs seeking vengeance on air crews for cities flattened in the Allies’ strategic bombing campaign. And SS officer Kurt Meyer ordered his men to take no prisoners during fighting following the Normandy invasion in 1944, and ordered the murder of Canadian prisoners at the Abbaye d’Ardenne.

It was no picnic after capture either. Germany was much better prepared for PoWs in the Second World War than it had been in 1914, eventually operating about 1,000 PoW camps within its own borders and occupied countries. But feeding them all and policing behaviour of guards and camp commandants proved a challenge.

Each of its armed services handled their own captives, although intermingling was inevitable. The Wehrmacht sent enlisted army prisoners to Stalags and officers to Oflags; a Stalag Luft awaited the Luftwaffe’s air force prisoners, while naval prisoners were sent to Marlag und Milag Nord by the Kriegsmarine.

Lessons had been learned in the previous war, particularly about prisoners’ pesky persistence at escape. Many of Germany’s Second World War camps were tailor made, with multiple rows of barbed wire, elevated guardhouses bristling with machine guns and frequent perimeter patrols with attack dogs. Knowing this would drive escape attempts literally underground, microphones were used to detect sounds of tunnelling. To prevent stockpiling supplies for escape attempts, the Germans opened relief food parcels, forcing PoWs to eat contents quickly. In petty vengeance, some guards mixed the contents into one unappetizing concoction.

The surest way to get back to England was to escape during transport to or between camps and hooking up with a resistance group (“Hush Hush Heroes,” March/April 2017 ). Once in a camp, the best option was not through the barbed wire, but under it.

“Life [at Stalag IXC] was a never-ending battle of wits between the prisoners and the Jerrys,” wrote A. Robert Prouse in Ticket to Hell via Dieppe. “Tunnels were constantly being dug and discovered.” Since escapes usually happened at night, guards began nightly head counts. Sometimes, several times at any hour of the night.

Germany’s prisoners of war were interrogated in transit camps before being sent on to permanent camps. The camps could be huge and crowded—about 130,000 prisoners were held in the largest, Moosburg’s Stalag VIIA, in Bavaria. Camp layouts varied, but usually featured one charcoal stove for heat, and rows of bunks. Common latrines were nicknamed 40-holers.

“They were pre-fab huts…wooden, and we started out with about four in a room…roughly 12 by 12 [feet],” said Flying Officer Jim (Pappy) Plant, quoted in Daniel G. Dancocks’ In Enemy Hands. “As the camp became crowded, we went up to six in a room…then we got eight in a room, then 12.” Close quarters and poor sanitation guaranteed copious vermin—flies, lice, fleas, bedbugs, rats.

Camps were uncomfortable, treatment crude and punishment harsh. For laughing and concealing a burning cigarette at roll call, Prouse was sentenced to seven days’ solitary confinement in a cold dungeon cell with a bare wooden bunk for which blankets were issued at night. His rations were withheld for defiance, and other prisoners sneaked him food when he went to the latrine.

As with their Great War comrades, Second World War Canadian PoWs were also preoccupied with food. “The rations were very poor and [initially] there was no Red Cross,” recalled Plant. “This is where most of us got our first real taste of hunger.” Flying Officer Arthur Low of Stalag Luft I in Barth said he went down to 120 pounds from 170. Pilot Officer Don MacDonald of Stalag Luft III in Sagan (now Poland) said “The food was the goddamnedest garbage you ever saw in your life.” The dogfish “smelled and tasted just like a ripe, wet collie.”

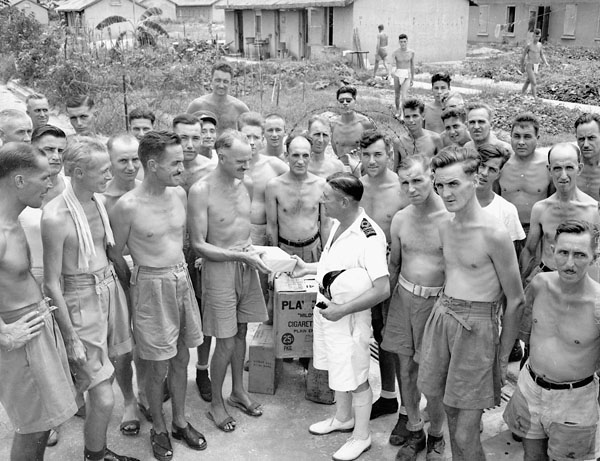

Prisoners looked forward to Red Cross relief parcels to augment their meagre rations, usually twice-daily soup and black bread and acorn coffee augmented occasionally with a little margarine or jam made from turnip or beets. “We lived from meal to meal,” said Stewart Ripley, quoted in Jonathan F. Vance’s Objects of Concern. “When we talked, we talked of food. When we didn’t talk, we thought about food.”

Life in prison “passed slowly,” wrote Prouse. “At times, it was boring and very discouraging. At other times, there was the tinge of danger that made it exhilarating, but the things that made it possible to endure were the comradeship and unselfishness of most prisoners, along with the humour of daily happenings.”

Asked to paint Christmas toys for the children of the wood factory where PoWs worked, Prouse and a buddy painted half the dancing dolls as skeletons, half as little Hitlers and named all of the toy battleships after the real ones sunk by the Allies. Prisoners at least enjoyed the joke.

In early days, Britain handled Canadian prisoners’ affairs, but by the end of the war a confusing number of Canadian departments were involved in different aspects of PoW care. With multiple offices involved, it could take some time for families to find out where their captured relatives had been sent.

In September 1939, the International Committee of the Red Cross began tracking Commonwealth prisoners. In November, the Canadian Red Cross Society re-established its operation in London and immediately began organizing parcels for Canadian PoWs. Although other aid organizations were formed, including the YMCA War Prisoners’ Aid and the Canadian PoW Relatives Association, the Red Cross was recognized in 1940 as Canada’s official voluntary aid society, responsible for dispatching food parcels to overseas camps.

As in the First World War, Canadians sent a steady stream of relief packages overseas. The Canadian Red Cross Society alone reported assembling and shipping nearly 16.5 million food parcels worth $47.5 million ($67 billion today). Crews of volunteers working in Toronto, Hamilton, Windsor and Winnipeg packed the parcels.

PoWs thought Canadian parcels were the best. Each five-kilogram parcel guaranteed 2,070 calories per day for a week, and included more than a dozen food items, including Klim milk powder, butter, cheese, corned beef, pork luncheon meat, salmon, sardines, dried apples and prunes, sugar, jam, biscuits, chocolate, salt and tea. Empty Klim tins were particularly handy and were fashioned into cooking and eating utensils (as well as digging tools and ventilation shafts for escape tunnels).

However, parcels were delayed, lost in transit or stolen by guards for their own use or to sell on the black market. Prisoners could go months after capture before relief packages began to arrive. Parcels were supposed to be distributed weekly, but often weren’t.

It was common practice to share parcels and provisions. Some prisoners formed small groups to share food, and others turned over food from parcels to hut cooks to stretch stingy camp rations.

“Red Cross parcels sure saved us,” said Flight Lieutenant John Downs of Carman, Man., quoted in Canadians in the Royal Air Force by Les Allison. Downs lost nearly 40 pounds in the weeks between the time Red Cross parcels ran out in early 1945 and when he was liberated in April.

Some parcels also contained entertainment items: cards, games, books, chess boards. (British Intelligence took advantage of this to hide escape kits in Monopoly games and game pieces [“The aircrew boot,” March/April 2016]).

Most camps had libraries and organized leisure activities to take PoWs’ minds off their stomachs with card tournaments, sports competitions, theatrical presentations, musical concerts—even college courses. Stalag Luft III had hockey teams and sports days. Camp actors presented dozens of plays and operettas, and there were performances by jazz and concert bands and orchestras.

“When we weren’t tunnelling or plotting escape strategy, our time was spent in pleasant pastime…or doing the less than pleasant tasks assigned us by the Jerrys,” wrote Prouse. The latter included emptying the latrines and sorting out putrid potatoes in storage.

Corporal R.J. Creighton of the Hastings and Prince Edward Regiment was the first Canadian soldier captured—when the Germans seized the hospital where he was recovering from a motorcycle accident in June 1940, just after the Dunkirk evacuation.

Canadians were taken prisoner in dribs and drabs until the first mass capture of 1,946 following the disastrous raid at Dieppe, France, on August 19, 1942, in which 907 Canadians died.

After the brutal battle, the prisoners were surprised to be treated with respect, even kindness, by German soldiers, as some recalled in Dancocks’ In Enemy Hands. “I expected they would kill us,” said Corporal Al Comfort of the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry. “But the Germans were not antagonistic at all…. No one was abused.” A German even took his own field dressing and applied it to Comfort’s thigh wound.

“I must say the Germans treated us with great respect,” said Sapper Wally Hair of the Royal Canadian Engineers. “They treated us as fighting men.” But no further kindness awaited at camp or en route.

At hospital in Rouen, France, said Comfort, no anesthetic was used as the German doctor removed shrapnel, then forced forceps through his leg back to front “and drew a gauze bandage through and cut both ends off.” The wound festered. “The infection soaked through my mattress and dropped on the floor. I remember holding the sheets down tight to keep the stench from choking me.” A hospital train took him to Obermassfeld, Germany, where British prisoner doctors properly dressed the wound.

In boxcars on the trip to Stalag VIIIB, “there was no place to go to the bathroom—just a tub that was sloppin’ over and stinkin’ like hell,” said Trooper Sid Hodgson of the Calgary Tank Regiment.

Most Dieppe prisoners were sent to Stalag VIIIB, where Dieppe prisoners were singled out for an unusual punishment. Orders had been found instructing raiders to tie German prisoners’ hands behind their backs to prevent destruction of documents they might have. The Germans demanded an apology and a promise never to bind prisoners again. Britain refused; Germany said there would be reprisals.

In October, Dieppe PoWs were called out in small groups. “We said, ‘Well, let’s show these sons of bitches how Canadians will die!’ We’ve got our chests stuck out, and we marched right in,” recalled Private Geoffrey Ellwood. Using the string from Red Cross parcels, the Germans proceeded to bind prisoners’ hands. “What they thought was one of the greats insults you could give to a soldier…and we stood there laughing! The relief was so great….”

“Our wrists got ulcerated with sores from the rope burns,” recalled Trooper Forbes Morton. Eating was difficult, going to the latrine the worst of all. The twine was removed only during the night. Red Cross parcels were also stopped, pending a British apology.

The string was exchanged for handcuffs in December. With a foot of chain between the cuffs, it was an improvement. Soon prisoners were refashioning keys from tins of New Brunswick sardines to open the handcuffs. “You’d pick the lock, put the cuffs in your pockets with the chain across the front of you. When you saw a German coming, you’d just slip your hands in your pockets and it would look like you were still chained,” said Trooper Fred Tanner.

In reprisal, Britain ordered the shackling of German PoWs, and Canada reluctantly followed, urging Britain to seek a diplomatic solution.

German prisoners in Canada strongly resisted. On October 10, when asked for 100 volunteers, a three-day brawl ensued in the Bowmanville, Ont., camp. Guards were showered with whatever came to hand—glasses, sports equipment, pieces of wood, cooking and eating utensils.

Eventually, PoWs were shackled. Canadian public opinion ran high against it. It was feared maltreatment of prisoners in Canada might result in reprisals on Canadian prisoners in Germany, and besides, humane treatment of prisoners is the moral high ground.

Britain and Canada stopped shackling in mid-December 1942. But Germany said its prisoners would stay in chains until the Allies apologized and forbade shackling altogether. For the Germans, it now was a matter of loss of face. Finally, the Red Cross persuaded them they could just stop the practice and save face simply by not announcing they had done so.

While the diplomatic face-off continued, level-headed guards on both sides of the Atlantic resorted to a more humane approach. Canadian guards reportedly dropped keys so PoWs could remove shackles between roll-calls. And German guards lightened up over time. Handcuffs were eventually collected in a box and “guys would just root through and pick out their chains and chain themselves up,” said Sergeant Tommy Cunningham of Stalag VIIIB. Guards “were getting fed up with it as well,” said Lieutenant Jack Dunlap of Oflag VIIB in Eichstätt.

Even without shackles, life in PoW camps was grim. Prisoners were often denied basic amenities. At Stalag VIIIB in Lamsdorf, the camp commander conserved electricity and water by turning lights on for the requisite time during daylight hours, and water on at night while prisoners slept, when nobody could benefit, said Corporal D.D. Johnstone.

As in all German PoW camps, food was a major concern and gave Canadians another reason to join work parties, which were “better as far as food goes,” said Trooper Jack Whitley of Stalag IID in Stargard. “The work parties also gave us a chance to steal food.”

A large proportion of enlisted men and volunteer officers assigned to work parties lived in small subsidiary camps attached to the factories, mines, quarries and sawmills where they toiled. Some even lived with farm families. Despite international agreements, prisoners were still put to work in war-related industry or at dangerous jobs with little thought for their safety. Many were killed in accidents.

But for Canadian slave labourers in Japanese PoW camps, death was far from accidental. After the war, the Tokyo Tribunal found that more than a quarter of Allied prisoners died in Japanese PoW camps—seven times more than in Germany and Italy.

About 2,000 Canadians were captives of the Japanese, the bulk of them Winnipeg Grenadiers and Royal Rifles of Canada dispatched to Hong Kong to bolster the garrison of 14,000 British and Indian troops. The colony fell on Christmas Day in 1941.

Of the 1,975 Canadians deployed, 1,685 were captured, of whom 264 died over the next three and a half years in Japan’s hundred or so brutal prisoner of war and work camps on its own islands and occupied territory.

The Japanese military lived by an ancient warriors’ code that decreed surrender shames your country, and prisoners were unworthy of humane treatment. Japan had not ratified the 1929 Geneva Convention, and in 1937, Emperor Hirohito decreed prisoners from China, Allied nations and the Philippines were not protected by the Hague Conventions.

Prisoners were murdered, used as slave labour and for medical experiments, starved and given poor medical treatment. “They were pretty rough on us” at capture, said Grenadier Private Don Nelson, one of many quoted here from in In Enemy Hands. “They tied our hands together with barbed wire.” Wounded prisoners “were cut loose and bayonetted right there.”

Canada’s first tussle with Japan over prisoners began with the simple identification of captives. It took a year and a half for Canada to receive names of those captured in the Battle of Hong Kong.

Camps were surrounded by barbed wire fences more than two metres high. Escape was nigh impossible, as Caucasian faces were hard to disguise in Asia, and few Westerners spoke local languages. Yet early on, before starvation sapped prisoners of their strength, a handful managed it, reaching Chinese guerillas. Those who were recaptured were routinely murdered—sometimes after torture. Four Grenadiers who escaped in August 1942 were beaten to a bloody pulp, then beheaded.

Nearly everything about camp life was in contravention of the Geneva Conventions. Requests for the exchange of sick and wounded military prisoners fell on deaf ears.

Open latrines and standing water meant camps teemed with insects—flies, mosquitos, bed bugs, fleas and lice. Prisoners could not keep themselves and their clothing clean—especially since soap was not routinely dispensed, nor provisions made for regular baths or showers.

Camps themselves were often in disrepair with poor water and electrical service, inadequate sanitation and heating. One prisoner recorded in his diary that there was no heat provided in huts in December 1942, when drinking water froze in buckets. If stoves were supplied, fuel sometimes wasn’t.

Although the temperature might plunge below freezing, not all prisoners were issued coats. Prisoners mended their shoes and socks until they wore out; footwear was rarely resupplied, and shoes that fit, even more rarely. Some prisoners ended the war wearing the same clothing, now rags, in which they’d been captured.

Prisoners prepared their own food from rations supplied—a daily teacup-sized bowl of rice (often crawling with maggots), miso soup and, early in the war, occasional fish or meat. Red Cross relief parcels were not routinely distributed; lucky prisoners received only a half dozen over the entire war, the unlucky, none at all.

Royal Rifles Sergeant Lance Ross in Hong Kong’s Sham Shui Po camp noted in his journal on Nov. 24, 1942: “We got some Red Cross stuff today. One ounce of bully beef per man per day and one ounce of raisins and we get half an ounce of cocoa a man per week—not bad.”

Some prisoners hunted rats to supplement their diets and prisoners grew kitchen gardens in some camps—but nobody ever had enough to eat.

“I wouldn’t have believed I could be so hungry,” said one PoW. “I’d chew grass, weeds, anything I could find. I would have stolen food from my friends, if they’d had any….”

“The lowest I ever weighed was 90 pounds. Normally I weighed 170,” said Private Bill Maltman, who toiled at a coal mine near Niigata.

Malnutrition, starvation and filth soon spawned disease. Prisoners died of diphtheria, dysentery, cholera, pneumonia, accidents and as the consequence of abuse. Vitamin B deficiency caused beriberi and pellagra (and a painful condition described as “electric feet”). Many were blinded by lack of vitamin A or by exposure to arc welders or chemicals on jobsites. The already scanty rations were cut for those too sick to work. Doctors were not given equipment or medicines.

“Seventy-four Canadians developed diphtheria before we could get any antitoxin, and of these, 54 died,” reported Stanley Banfill, a doctor who testified at war crimes trials. “Subsequent events showed that antitoxin was obtainable in Hong Kong, so these deaths must be attributed directly to callousness or carelessness on the part of our captors” in Sham Shui Po.

Medical personnel—not guards or camp administrators—were often punished when prisoners died. Ross noted that after two deaths, 40 orderlies were told to take off their shirts, then beaten with wide rubber bands.

Most prisoners were able to communicate with their families only once or twice during years of captivity. Stacks of undelivered letters to and from prisoners were recovered in camps after the war.

Permission for neutral inspectors to visit camps was routinely turned down. Camp commanders refused to answer questions of the few inspectors allowed in. Prisoners who complained to inspectors of their treatment were often beaten after the visit.

Saskatoon’s Flight Lieutenant Les Chater, who worked as an engineer at Royal Air Force airports, was captured in Java in March 1942 and moved to PoW camps in Japan. His diaries noting daily contraventions of international law, including beatings, starvation and murders, were used at Tokyo war crimes trials and reproduced in 2001 in Behind the Fence: Life as PoW in Japan 1942-1945.

Every one of the 1,418 Canadian prisoners liberated in 1945 had chronic health problems. Two years after liberation, more than 70 per cent of Hong Kong prisoners at a veterans’ hospital in Winnipeg still had intestinal parasites, ringworms, whipworms, hookworms and threadworms.

Some Canadian PoWs in Europe witnessed or experienced the horrors of Nazi concentration camps, where so-called enemies of the state, including Jews, intellectuals, gays and Jehovah’s Witnesses, were starved, beaten and worked to death. Some Canadian spies were sent to such camps prior to execution (“Hush Hush Heroes: Part 2” March/April 2017).

In August 1944, two dozen Canadian airmen were among 168 Allied evaders being spirited to safety by the French Resistance. The operation was betrayed, and the airmen were arrested as spies. They were beaten, tortured and sent to Buchenwald Concentration Camp. They were met by dogs and whips and “thousands of walking human skeletons,” said Ed Carter-Edwards in a speech at a memorial service at Buchenwald in 2014. “We saw the smoke pouring out of the chimney” at the crematorium, which, they observed during their three-month stay, operated ceaselessly. More than 34,000 prisoners died in Buchenwald during the war, starved, beaten or worked to death.

But this was not to be the fliers’ fate. Just days before the order was issued to execute all airmen in the camp, “the Luftwaffe saved us,” said Carter-Edwards, perhaps out of professional courtesy, perhaps to prevent reprisals on German prisoners. He spent the remainder of the war in Stalag Luft III, best known for The Great Escape of 1944.

Tunnels were constantly dug and discovered in camps throughout Germany. Some prisoners felt it was their duty to escape—even if they failed, the search for them would tie up men and resources. Others found planning and preparing escapes made them feel less helpless.

Molsdorf was so riddled with tunnels that prisoners were moved to a new, supposedly escape-proof prison in Mülhausen in September, 1943, reported Prouse.

Only a few of the thousands who attempted to escape German camps were successful (Vance says only three of the 2,500 RCAF members who tried to escape a camp made it to freedom). Even in mass escapes, only one or two generally made it to safety.

The 1963 American film The Great Escape showed the courage, subterfuge, ingenuity and luck necessary to provide escapers with civilian clothes and false papers. Contrary to what was depicted in the film, no Americans were among the PoWs who escaped from Stalag Luft III on March 24-25, 1944. But nine Canadians were.

About 600 PoWs, a quarter of them Canadian, were involved in the preparations. It took more than a year to dig the tunnels and prepare the escapers’ paperwork and clothing. RAF Squadron Leader Roger Bushell, shot down in 1940, and with two escape attempts already under his belt, was the mastermind. He envisioned more than 200 men escaping through a tunnel running under the camp and its barbed wire fences, to emerge in a nearby forest and spread through the countryside. To avoid microphones, the tunnels were more than nine metres down.

The Tunnel King was Canadian Spitfire pilot Wally Floody, a former gold miner shot down in October 1941. He had been sent to Stalag Luft III after trying—twice—to dig his way to freedom.

Prisoners used bed boards to shore up the walls, Klim powdered milk cans from Red Cross parcels to fashion ventilation shafts and digging utensils, socks and long underwear to carry away soil for discreet disposal. Blankets, bolsters, mattress and pillow ticking, prisoners’ uniforms and pilfered clothing were used to fashion civilian clothes. Guards were bribed to supply maps, train timetables and up-to-date copies of travel documents. Prisoners secreted maps and money issued to them in case of capture, and the guards did not catch all escape aids carefully hidden in contents of relief packages.

Three tunnels—code-named Tom, Dick and Harry—were dug, lest any were discovered. Good thing, too. Dick had to be abandoned due to camp expansion but was used as a sand dump once snow covered the ground. Tom, the 98th tunnel uncovered in the camp, was discovered in November 1943.

Among the escapers was Thompson, Canada’s first PoW, but not Floody, the Tunnel King. Sensing something was in the works, the Germans transferred a score of prisoners, including Floody, shortly before the escape.

The escape—through Harry—was plagued with problems: it took more than an hour to open the frozen exit trap door; walls collapsed and needed fixing; an air raid caused a blackout; and the 100-metre tunnel was not quite long enough—coming up 28 metres short of the woods and close to a guard tower. So instead of a steady stream of more than 200 escapers, fewer than 80 made it out, timing their dash to the woods to avoid catching guards’ eyes.

Only three—one from Holland and two from Norway—got back to England. Everyone else was caught; 50 were murdered between March 29 and April 14, 1944. Thompson was not among them. After the war, he became a lawyer, then a judge. Floody, who was awarded the Order of the British Empire, helped found the RCAF Prisoners of War Association.

At the end of the war, one final ordeal claimed many prisoners’ lives. In January 1945, in advance of the Russians’ approach, Germany began emptying its camps to concentrate PoWs inside German borders.

Prisoners, in poor physical condition from months and years of abuse and starvation, were forced to march up to 30 kilometres a day, some for as long as six weeks, sometimes in blinding snowstorms and bitter cold, dragging along provisions from the camp. They dossed down in barns and outbuildings and fields. When supplies ran out, they were forced to scrounge for food and drink from ditches. Soon the cold, starvation and illness were killing prisoners.

In early April 1945, Prouse found himself in a column of prisoners and refugees outside a town being bombed. Allied planes, mistaking the column as marching soldiers, began machine-gunning. An officer “quickly laid two long strips of white cloth side by side, a signal meaning ‘PoWs in danger,’” recalled Prouse. He later used the same technique on a roof in Stalag IXC near Bad Sulza when a squadron of fighters mistakenly targeted the camp.

Many prisoners lost their lives on the road. “Many men gave up, too sick and weak to march any farther,” Prouse recalled. “The guards finally gave up trying to prod them to their feet and left them where they lay, either to die or make it later on their own.”

As the front moved closer, PoWs in camps were in greater and greater danger. When sounds of battle neared, guards in Stalag IXC tried to force the prisoners to leave the camp. “Not a man moved,” said Prouse, not even under threat of being shot. “The whole camp was determined that this was it: freedom was too near.” Guards fled when they could hear tanks approaching.

The American Third Army liberated the camp, “showering us with cigarettes and field rations. One trooper even stripped off his battle jacket and handed it to me, no doubt feeling sorry for my ragged appearance.”

The forced marches concentrated prisoners in huge camps which could not easily be supplied in the chaos. Liaison officers left by liberators at each German camp arranged temporary supplies and an airlift as soon as possible from the nearest airfield. Unlike the weeks and months of delay during the First World War, some PoWs in Europe were back in England within days of liberation.

Not so for prisoners of the Japanese, many of whom arrived home months after VJ-Day.

Although Hiroshima had been bombed on Aug. 6, 1945, and Nagasaki three days later, Les Chater and other prisoners at the Kanose work camp at a carbide plant near Niigata learned only on Aug. 15 that the fighting had stopped. The camp commandant “rushed out of camp with sword and revolver on,” followed by the guards. Work shifts were cancelled. Rumours were rampant. When the air-raid post was shut up and flags brought down, “That decided me,” Chater wrote in his diary. Then followed a period of limbo before liberation. “Queer feeling, free and not free. Time will drag now!”

Planes began dropping food and medicines into camps. Control passed back to Allied officers and prisoners in some camps were given freedom of local towns.

On Sept. 2, the day Japan formally surrendered, Chater’s diary entry reads: “Guns, etc., of administration staff turned over to us.” Chater boarded a U.S. ship for home on Sept. 18, and arrived in Vancouver on Oct. 8.

The former prisoners of the Japanese, though dispersed across the country, were later united in a decades-long fight for compensation and veterans’ benefits—and an apology from Japan. On Dec. 8, 2011, Japan apologized to Canadian veterans. By then, most who had suffered at their hands had died.

The horrors of Second World War concentration and prisoner of war camps sparked another expansion of the Geneva Conventions in 1949, but neither the publicity from that—nor participants’ signing of earlier agreements—were of any help to the 33 Canadians captured during the Korean War in 1950-53.

Both sides in the Korean War (the United Nations with South Korea and China with North Korea) applied exceptions to the conventions. The United Nations was reluctant to repatriate PoWs, since many claimed they were unwillingly conscripted and were loath to return to the communist-controlled countries. And North Korea did not consider South Korean soldiers to be enemies, but either misguided countrymen or traitors. The former were added to the North Korean army and sent to the front lines or assigned dangerous war-related work; the latter were, at best, sent to special re-education camps for indoctrination in communist ideology, at worst, executed.

For other Allied prisoners, “the mental torture…was worst of all,” recalled George Griffiths in John Melady’s Korea: Canada’s Forgotten War. Captured on Oct. 23, 1952, when some 30 Canadians were overrun by Chinese troops, he was wounded in a grenade explosion. Dragging one leg, he was one of 14 Canadians captured and led through miles of underground tunnels, then marched for 10 or 12 days to a prison camp in North Korea. His wounds went untended for 10 months.

Along the way, three prisoners were put in a dark hole where ice-cold water was dripped on their bare backs for hours. “Gradually it became extremely painful. I am certain that if they had continued it long enough, we would have gone insane,” Griffiths wrote.

At the camp, where Griffiths remained for 10 months, mental torture was used to get PoWs to sign untrue statements, that they had entered Chinese territory, that they thought the war was unjust. They were threatened with death, half-starved, had their mail cut off, were screamed at for hours.

Treatment mirrored that of the worst camps of the Second World War: about 40 per cent of UN prisoners died in captivity from starvation, disease and untreated wounds.

At the end of the war, the shrapnel was finally removed from Griffiths’ legs and he once again marched back south, camp to camp, to Freedom Village at Panmunjom. Prisoner exchanges were part of the 1953 armistice between the UN and North Korea, although it is suspected that several hundred UN and perhaps tens of thousands of South Korean soldiers were not returned and were unwillingly retained.

In the Great Switch prisoner exchange, all remaining Canadian prisoners—all but one—were freed.

That last unlucky PoW was RCAF fighter pilot Andy MacKenzie, shot down by friendly fire in December 1952 and kept in a Chinese prison until 18 months after the war ended. (“The last PoW”, November/December 2017).

He was starved, put in solitary confinement, denied heat in winter. He tried twice to escape, once when his body was covered in gigantic body lice. “A million of them on my body and I was going crazy.” For 93 days, he was made to sit on the edge of his bed, unmoving, and stare all day, every day, at a wall.

“It is difficult to describe the mental torture,” said MacKenzie. “I never thought I would leave that cell alive.” He was relentlessly interrogated and urged to sign a phoney confession that he had been shot down in Chinese air space. He resisted for months, “I kept thinking of what was going to happen when I got home. Would I be court-martialled?

“The torture was all mental…. My body ached, but my mind kept on working, wondering what was coming next, what they would do with my body after it was all over, that sort of thing.”

Eventually, when it seemed to him he was of no more propaganda value, he did confess.

“They marched me across the border into Hong Kong and I was free. The date was Dec. 5, 1954—exactly two years to the day after I was shot down.”

Between 1945 and 1948, nearly 25,000 people were tried for war crimes in Europe and Asia, UN War Crimes Commission documents show. Tens of thousands more were tried in the Soviet Union.

War crimes trials began for The Great Escape murderers in 1947; 27 were executed, 17 imprisoned; 11 committed suicide. Colonel Tokunaga Isao, Sham Shui Po camp commandant in Hong Kong, and his medical officer, Saito Shunkichi, implicated in the deaths of 128 Canadians, were sentenced to death in 1947. Their sentences were later commuted to life in prison, then 20 and 15 years, respectively.

It has taken a century and a half, but 194 countries have now signed and ratified, making the Geneva Conventions “universally applicable,” for both prisoners of war and civilian captives, says the International Committee of the Red Cross.

The war crimes trials of the 1940s and 1950s showed the power and scope of the international agreements; alas, not everyone plays by the civilized rules.

Soldiers can be captured by terrorists or rebels who torture and rape them, throw them into dank cells and black holes, ransom them, use them as human shields and execute them—too often on videos meant for public broadcast.

And there are still disagreements and hair-splitting over definitions. Waterboarding, which the International Red Cross says is torture, was used by the United States on terrorism suspects in the early 2000s in Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq, among others, and defended by a former vice president, who said as it had been used in the training of American soldiers, it could hardly be described as torture.

There has been great progress in improving the treatment of prisoners of war, but prisoners can never be completely protected. Some leaders consider themselves above the law and troops will continue to succumb to emotion in the heat of battle.

And evil still lurks in the hearts and minds of some captors. For their unlucky prisoners, international laws may not provide protection, but perhaps some measure of justice.

.jpg)

.jpg)