“You’re too old.” Those were the words First World War veterans Clarence Wade and William Swim were confronted with when they tried to re-enlist in 1939. The former soldiers were being denied, even though both had ample wartime military experience. They were in their 40s and were being passed over for younger recruits. The reason? The rules of enlistment considered them too old.

But Wade and Swim and other veterans of the Great War, many decorated war heroes, were determined to serve their country again—in some capacity. Undeterred by their initial rejection, the veterans took their case to Parliament. Eventually, the government saw the error of its ways and on May 23, 1940, Minister of National Defence Norman McLeod Rogers declared “it had been decided to establish a force to be known as the Veteran’s Home Guard for the adequate protection of military property on the home front.”

In addition to bases, arms factories and myriad other military installations, Canada operated 40 internment and prisoner-of-war camps across the country during the Second World War.

Prisoner-of-war camp at Sherbrooke, Que., on Nov. 19, 1945. [LAC/PA-114463]

The men responsible for guarding the internment camps were pulled from the ranks of the Veterans Guard of Canada (VGC), the renamed Veteran’s Home Guard. By taking over guard duties from the Canadian Provost Corps (the military police of the Canadian Army), the VGC helped free up younger Canadians for overseas service.

The government also adjusted the age requirement to a more lenient “under 50.” Even then, many men lied about their age in order to serve their country again. By 1943, the VGC was more than 9,800 strong.

Only one of those internment camps was located in the Maritimes: Camp B70, a six-hectare fenced compound in Ripples, N.B., east of Fredericton.

Camp B70 saw two phases of activity. In phase one, from 1940 to 1941, the camp held 711 prisoners, mostly German and Austrian Jews who had fled Nazi Germany to England before British authorities—worried there might be spies among them—transported them to Canada for incarceration. In phase two, from 1941 to 1945, the camp held 1,200 German and Italian merchant marines, as well as many Canadians who had spoken out against the war or were deemed by the government to be Nazi sympathizers.

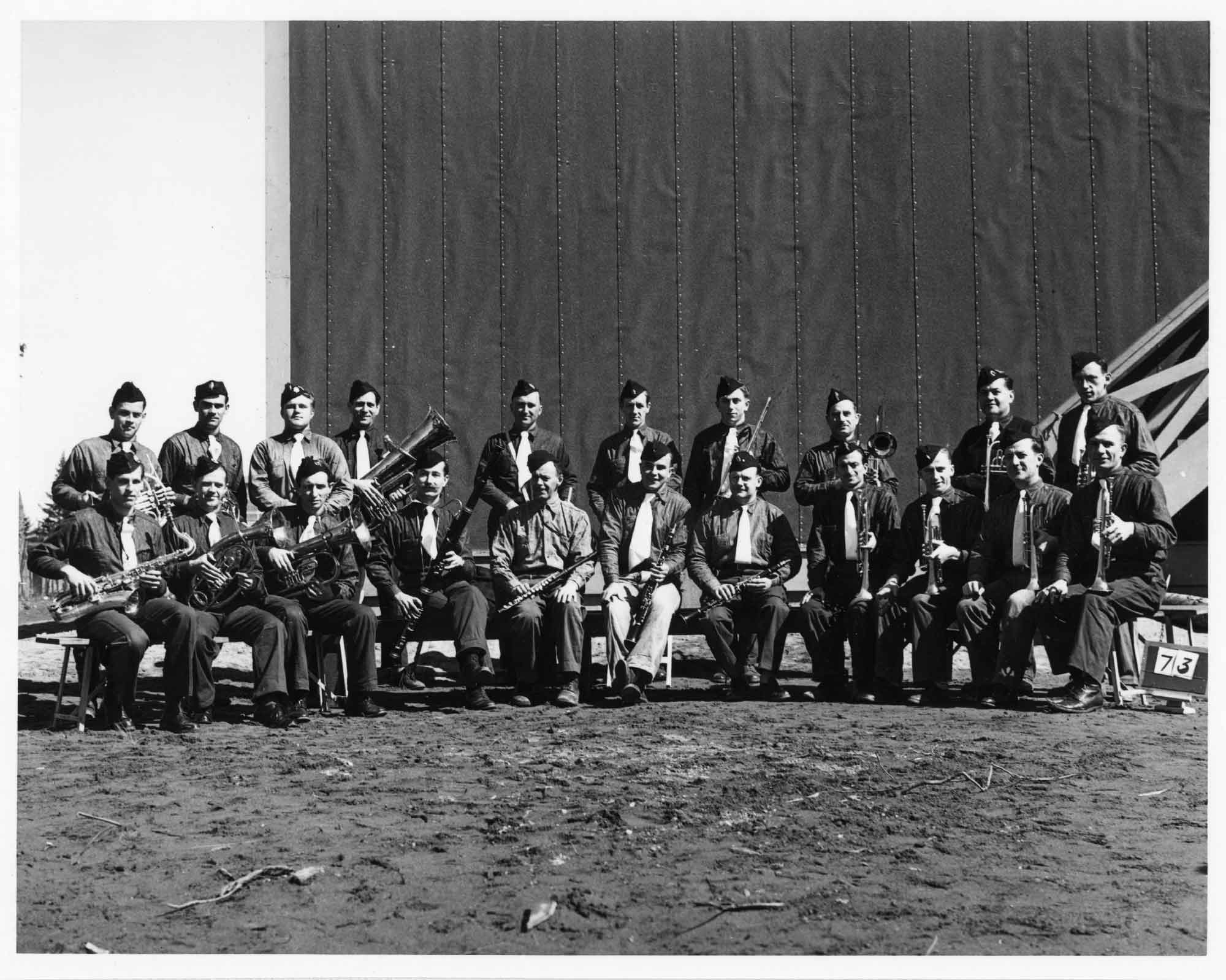

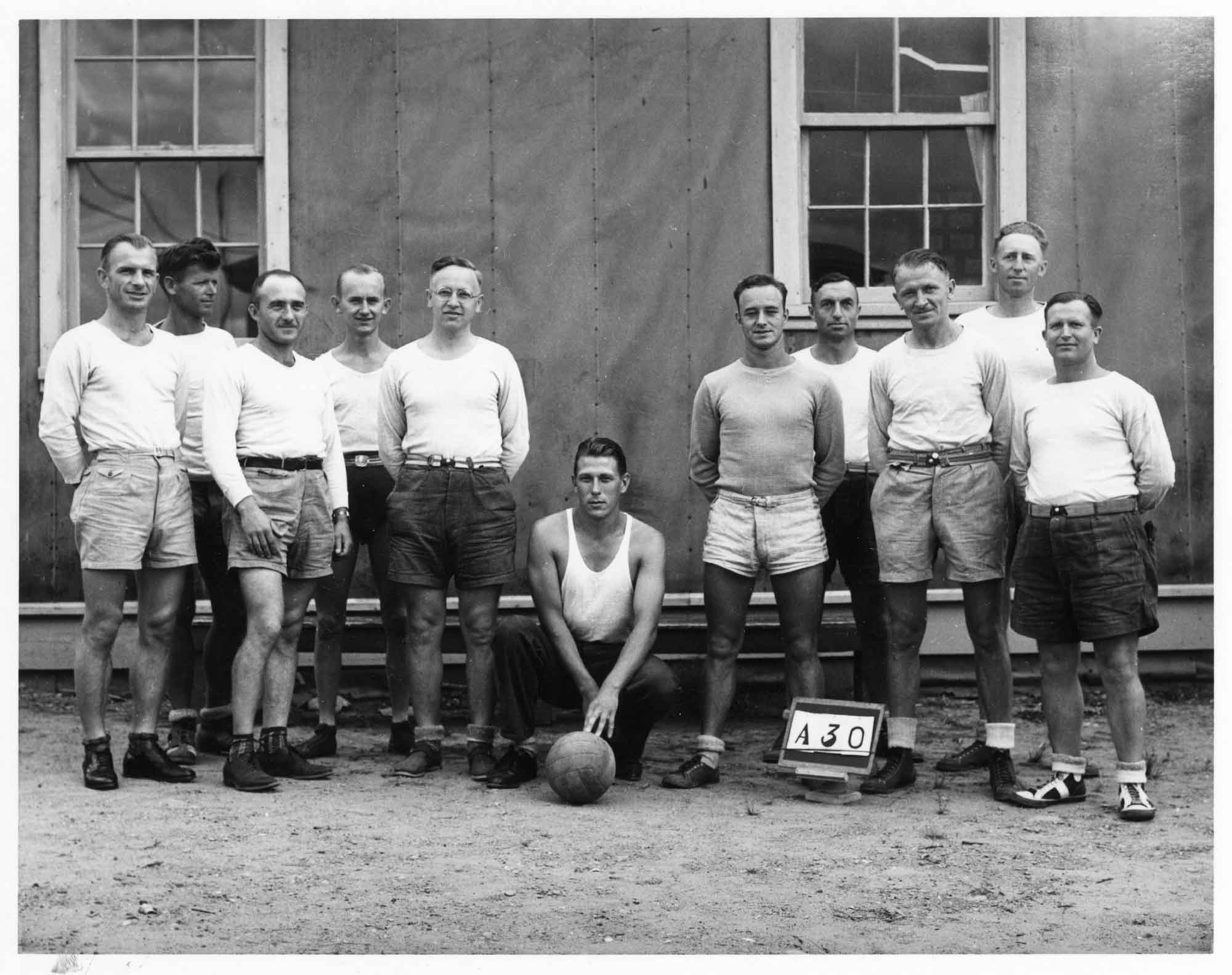

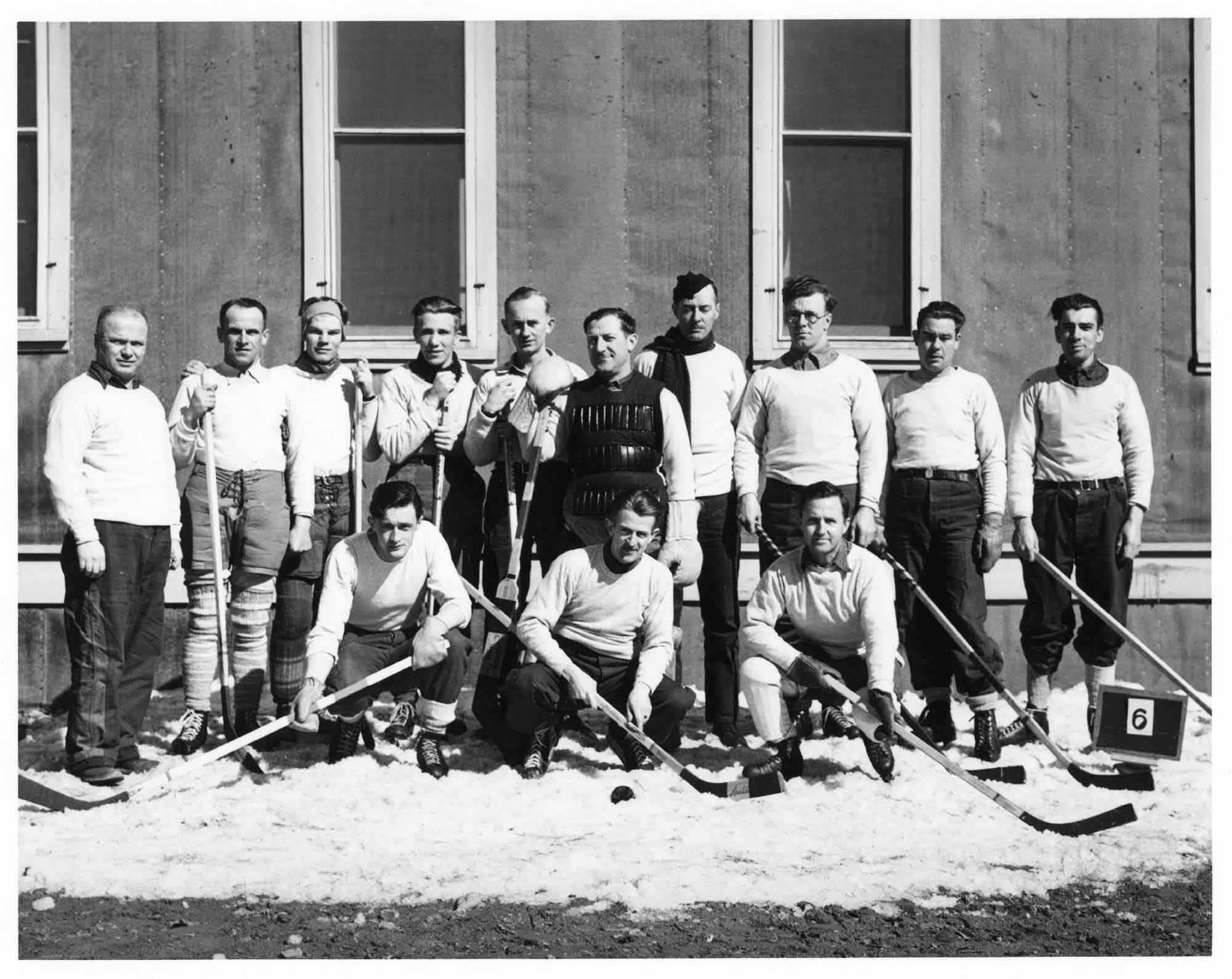

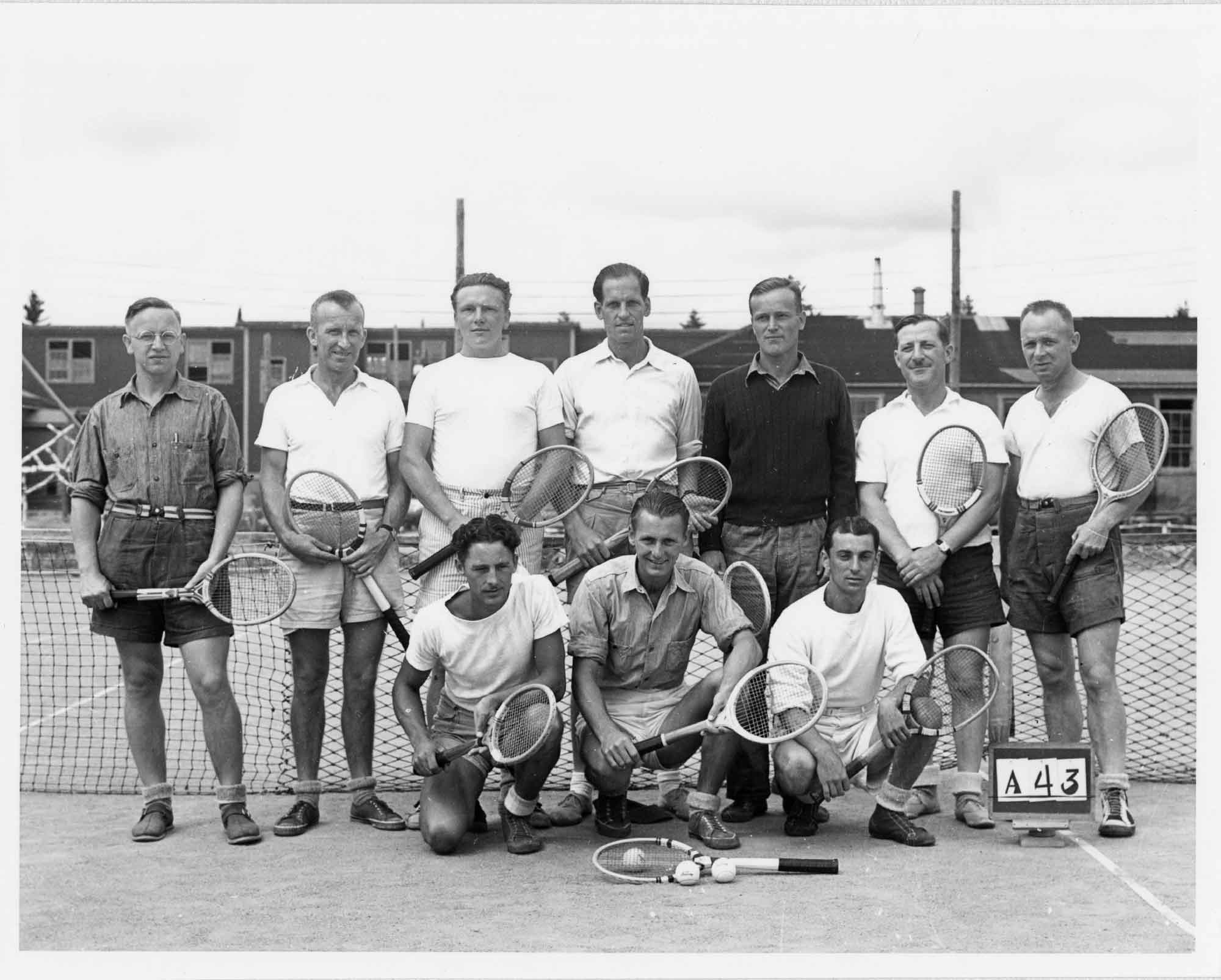

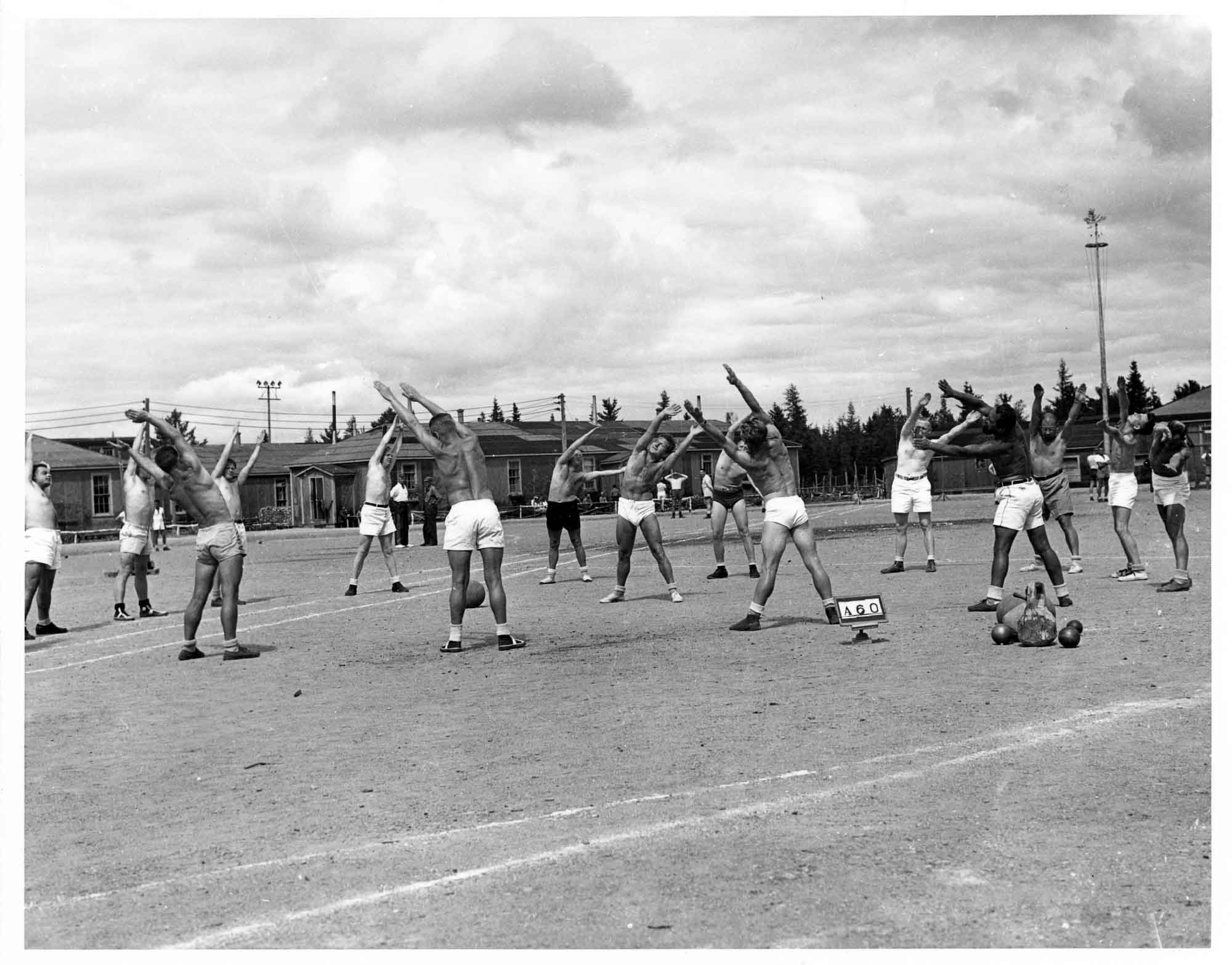

Photos from Camp B70

Photos courtesy of Provincial Archives of New Brunswick

Members of the VGC were rotated periodically between Camp B70 and other camps across Canada. Although these men were war veterans, the prospect of guarding Second World War prisoners was a new experience. The guards did not know what to expect when the first prisoners arrived from Europe.

VGC member George Mossman was there—gun loaded and bayonetted—when the first internees arrived, according to Ted Jones, author of Both Sides of the Wire, a history of B70. But “they were a harmless lot,” Mossman recalled.

“As veteran guards, we were green and knew nothing of the Geneva Convention,” VGC Major Gordon Cuming admitted. As such, guards at Camp B70 fraternized with internees regularly. Moreover, a healthy respect and even friendships developed between many guards and prisoners.

Guarding prisoners of war was not glamorous or exciting work, and the guards’ working conditions were quite meagre. The guards had the same rations as the prisoners, said Wade. Even though they were poorly equipped, often with footwear ill-suited for the frigid temperatures and snow of New Brunswick winters, the guards performed their duties admirably.

Many of the men had to walk to the camp from their homes, some from as far away as Fredericton, Oromocto and Douglas, by hitchhiking, cycling or getting rides any way they could. Guard Wilfred Wade of Fredericton recalled leaving his wife and five children at home for the 60-kilometre round-trip walk to the camp for his rotation. To make travel matters worse, most internment camps were in intentionally isolated locations and Camp B70, in the mosquito-infested forests of New Brunswick, was no exception.

Regardless of the hardships of duty, many guards have fond memories of their rotations at Camp B70, partly because the rules and oversight were not overly rigid. For example, the sentry towers made for great hunting blinds.

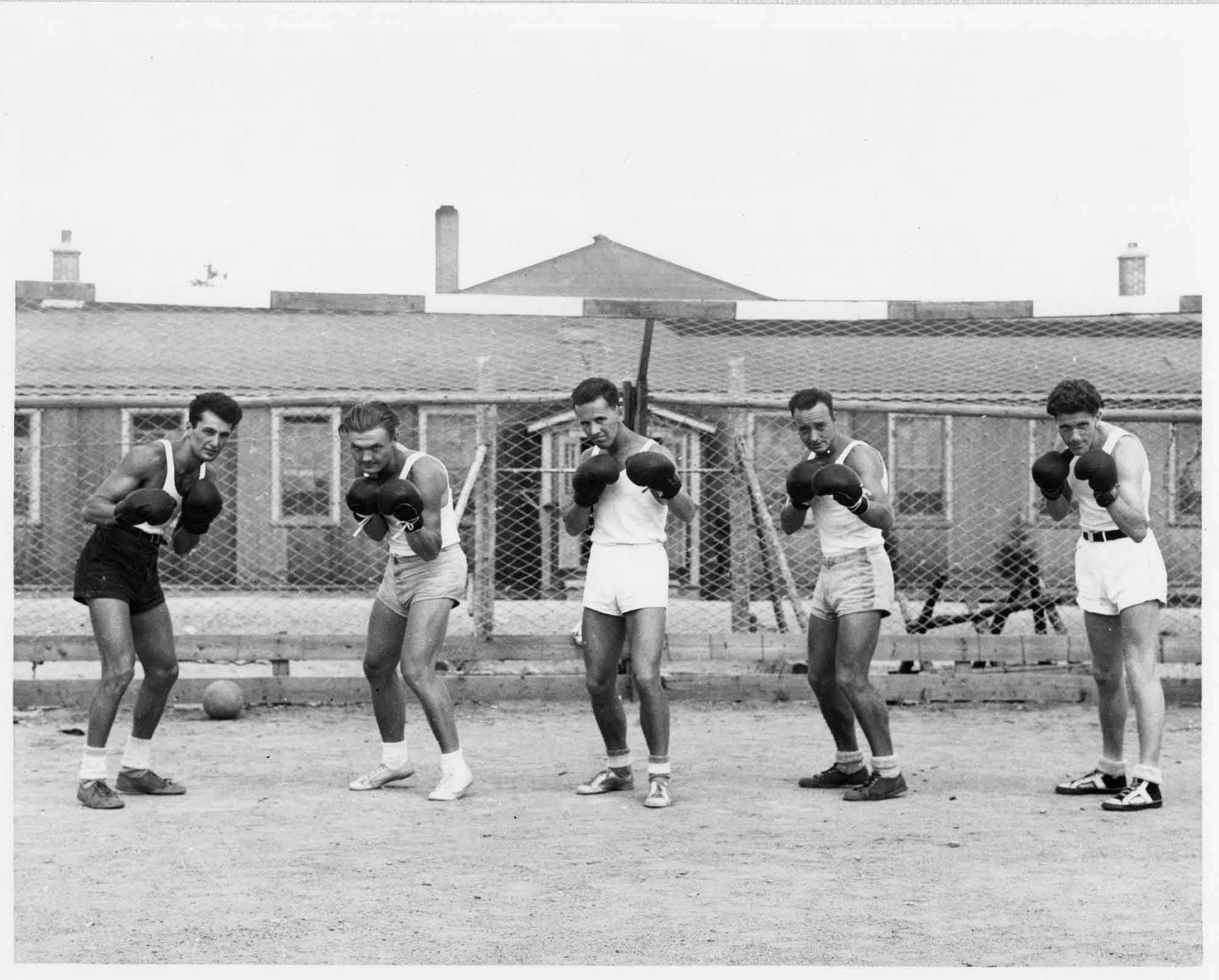

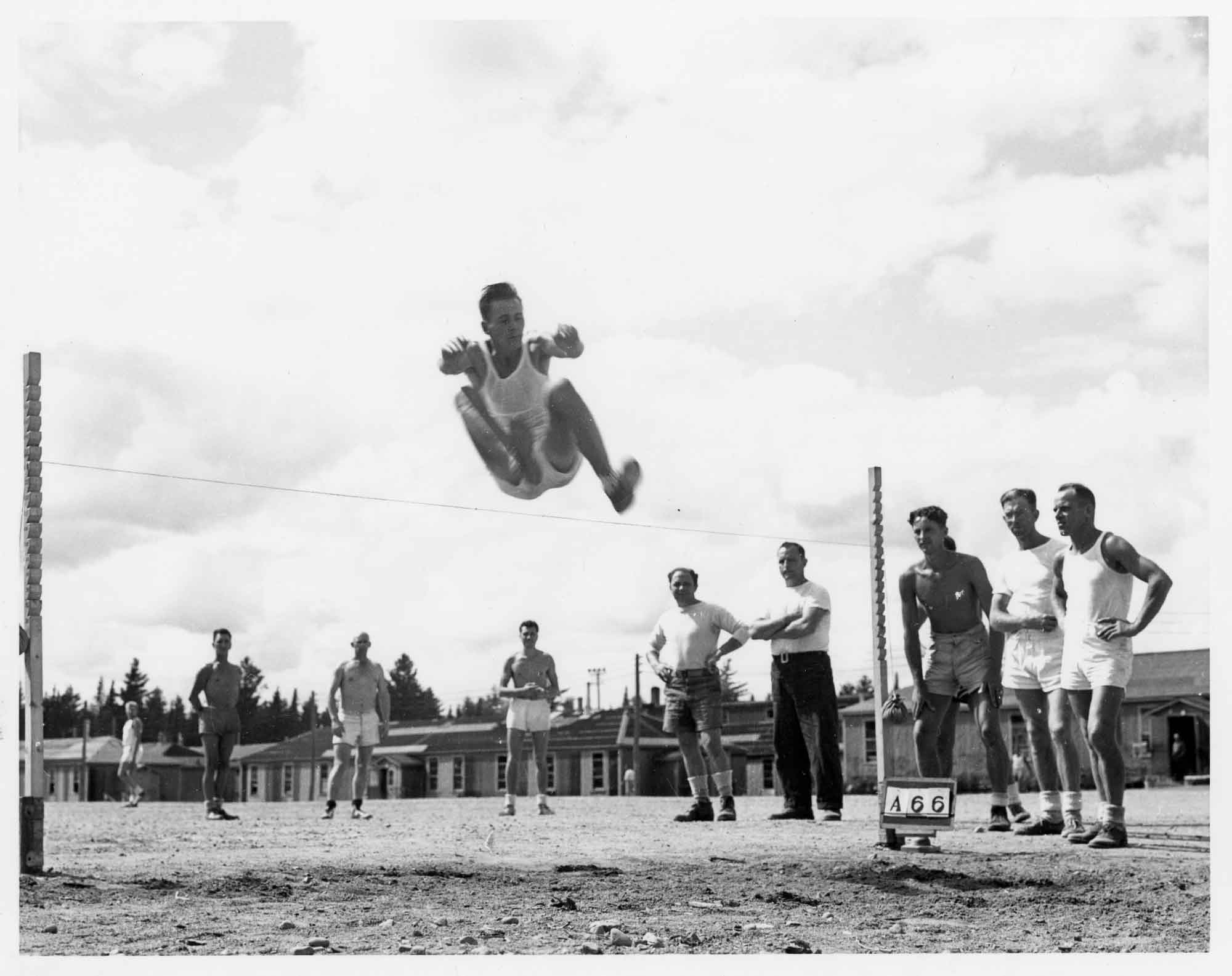

German prisoners of war put on an athelitics demonstration at Camp 23 at Monteith, Ont. [Canadian War Museum]

The guards were known to shoot a deer or two from the towers while on duty and dress the animals on the spot, according to Clarence Wade. The meat was then divided among guards and prisoners alike. Dances were held on weekends and women from local communities were invited to the camp to dance with the guards. The prisoners even performed music concerts, tiny circuses and other events for the guards’ enjoyment.

The relationship between guards and internees remained friendly and congenial for the most part. Many guards couldn’t read, so some prisoners who had learned academics in their home countries, such as Germany and Austria, would read the guards’ mail to them and write letters home for them. Many internees spoke English and at least one German-speaking guard, Albert Watters, developed friendships with some of the German internees.

The VGC remained on active service until 1947. Even though its contributions may represent only a footnote in the greater narrative of the Second World War, these men chose to serve in not one war, but two. And in spite of their age limitations, the men who were not allowed to fight overseas on the front lines performed all duties asked of them.

After the war, the camp’s 52 buildings were sold to individuals and businesses in surrounding towns and villages and relocated. Some of them are still used as homes or summer cottages in the region.

Sixteen kilometres east of the original camp, in the village of Minto, N.B., is the New Brunswick Internment Camp Museum, one of only two such museums in Canada and five in North America. Here the memories and contributions of the VGC men who guarded Camp B70 are preserved and commemorated.

The museum’s commemoration efforts have resulted in a supportive two-way street, said director and curator Ed Caissie. Many guards and their families have donated time, money and artifacts and, in turn, the museum has been able to acknowledge their contributions to the war effort.

Photos from Camp B70

Photos courtesy of Provincial Archives of New Brunswick

For example, a large internee-crafted wooden ship given to guard Charles Collins was recently donated by his daughter-in-law. The artifact and Collins’ story now live on at the museum. Some of the links between the camp, the town’s history and the museum are deeply personal. One guard from nearby Minto happened to show a picture of his teenage daughter to an Italian prisoner.

“The Italian was so enamored with his daughter that he wished to come back after the war to marry her,” said Griffin Mountan, the museum’s summer supervisor. “To show his sincerity, the internee gave the guard rosary beads to give to his daughter. The Italian internee never made it back to Canada after the war, but the daughter, Marion Goguen, grew up to become one of the museum’s first board members.”

The museum’s collection includes more than 600 artifacts and objects associated with the original camp, including several prisoner-made jewelry boxes, which were often bartered with or gifted to guards. Photographs, artifacts, oral histories and interactive exhibits help museum visitors experience life through the eyes of the internees, guards and other camp personnel. Special emphasis is given to the experience of incarceration, constitutional issues, violations of civil liberties and civil rights, as well as the broader issues of race and social justice.

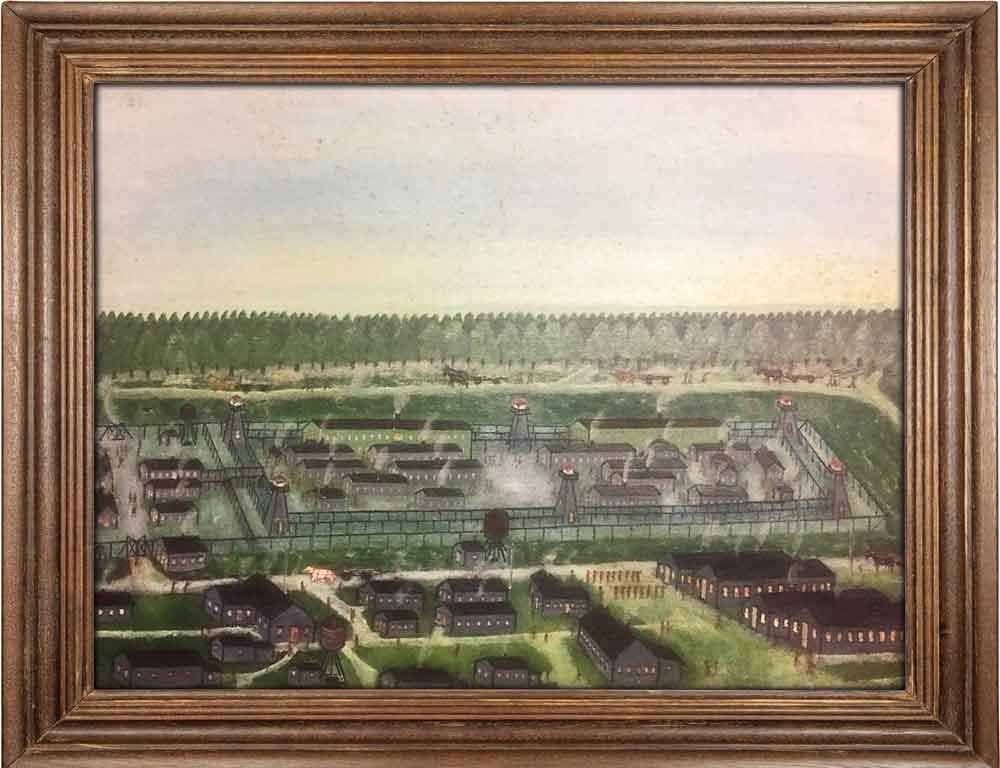

A painting by former guard William Swim of Internment Camp B70 near Ripples, N.B. [New Brunswick Internment Camp Museum]

One artifact is a painting by Private William Swim, who found artistic inspiration during his tenure as a guard at Camp B70, according to his daughter, Susan Pitman. Years after serving there, he painted from memory a scene of the camp buildings that, thanks to Pitman, now hangs in the museum. The painting evokes a serene pastoral quality and offers a guard’s-eye view, although there are no people depicted in the barbed wire-enclosed section of the camp.

The stories of the VGC exemplify how much a country can accomplish in a time of crisis when everyone contributes to the greater cause. It also highlights just how important it is that institutions like the New Brunswick Internment Camp Museum continue to preserve these histories for future generations.