From the first velvety phut of the shell burst to those corpse-like breaths that a man inhaled almost unawares,” wrote Private John Lynch of the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry. “It lingered about out of control.

“When he fired it, a man released an evil force that became free to bite friend or foe til such time as it died into the earth. Above all, it went against God-inspired conscience.”

Lynch depicted mustard gas as a supernatural force and a weapon that was almost impossible to control. It must have seemed like pure evil to many front-line soldiers, protected by only a flimsy respirator. While the initial gas clouds of 1915 were dangerous to all in the battle zone, with wind often blowing the deadly fumes back against those who unleashed them, chemical weapons by 1917 were better controlled, even if they remained terrifying to all soldiers.

Canadians on the Western Front were familiar with poison gas. They were among the first victims of the chlorine cloud attack at the Second Battle of Ypres in April 1915. And over the next two and a half years, they faced chemical weapons on multiple occasions. But they were also issued effective respirators and trained in an anti-gas doctrine that helped educate and protect them on the battlefield. At the Battle of Hill 70 in August 1917, however, they encountered a new and particularly nasty type of chemical: mustard gas.

After the stunning victory at Vimy in April 1917, where the Canadians wrestled the ridge away from the Germans, they continued to advance eastward, slowly moving across France’s Douai Plain.

The city of Lens was a fortified strongpoint in this sector and British First Army ordered the Canadians to attack it to support the stalled offensive at Passchendaele to the north. On that front, east of Ypres, British soldiers had attacked at the end of July, but rain and shellfire had turned the battlefield into a bog, miring the offensive in mud.

On the Lens front, about 60 kilometres to the south of Ypres, Arthur Currie, the newly appointed Canadian Corps commander, was ordered to launch a diversionary attack that would hold the German divisions here and ensure they were not sent northward to Passchendaele.

Currie had long advocated using gun power instead of manpower to achieve his battlefield goals. But even a set-piece artillery and infantry attack against Lens would be difficult and costly, as the enemy was dug into the shattered city, with every building and basement fortified, rubble-filled streets channeling attackers into kill zones, and all the other challenges of fighting through an urban environment.

After studying the ground, Currie and his staff instead planned for the 1st and 2nd divisions to capture Hill 70, northwest of Lens, and hold it against counterattacks.

A diversion by the 4th Division farther south would draw German attention away from the true battlefield.

Corps intelligence predicted that “the enemy had no intention of giving up Lens or the ground near it.” Currie’s goal was not terrain, however, but to establish firm defensive positions from which to repel counterattacks and kill as many German troops as possible.

The enemy had an established doctrine of immediate counterattack, so Currie planned for not only the initial attack, but also to cut down the Germans as they surged out of their trenches, crossed no man’s land, and tried to retake the lost territory. Currie’s troops would meet the exposed Germans with crossfire from artillery, machine guns and rifles.

Germany was the leader in gas warfare because of its strong pre-war chemical industry and skilled scientists. It had been first to introduce chlorine gas and then phosgene, which was even more lethal. On the night of July 12, 1917, it turned to a new chemical agent that burned, blinded and killed.

Mustard gas—dichlorodiethyl sulphide—took its name from the mild aroma of mustard that alerted one to its use. Mustard gas shells were marked with a yellow cross and contained an oily liquid that transformed into a vaporous gas when the shell burst, diffusing it over a limited area. It took many gas shells to build up to a lethal density, but even low doses caused injuries.

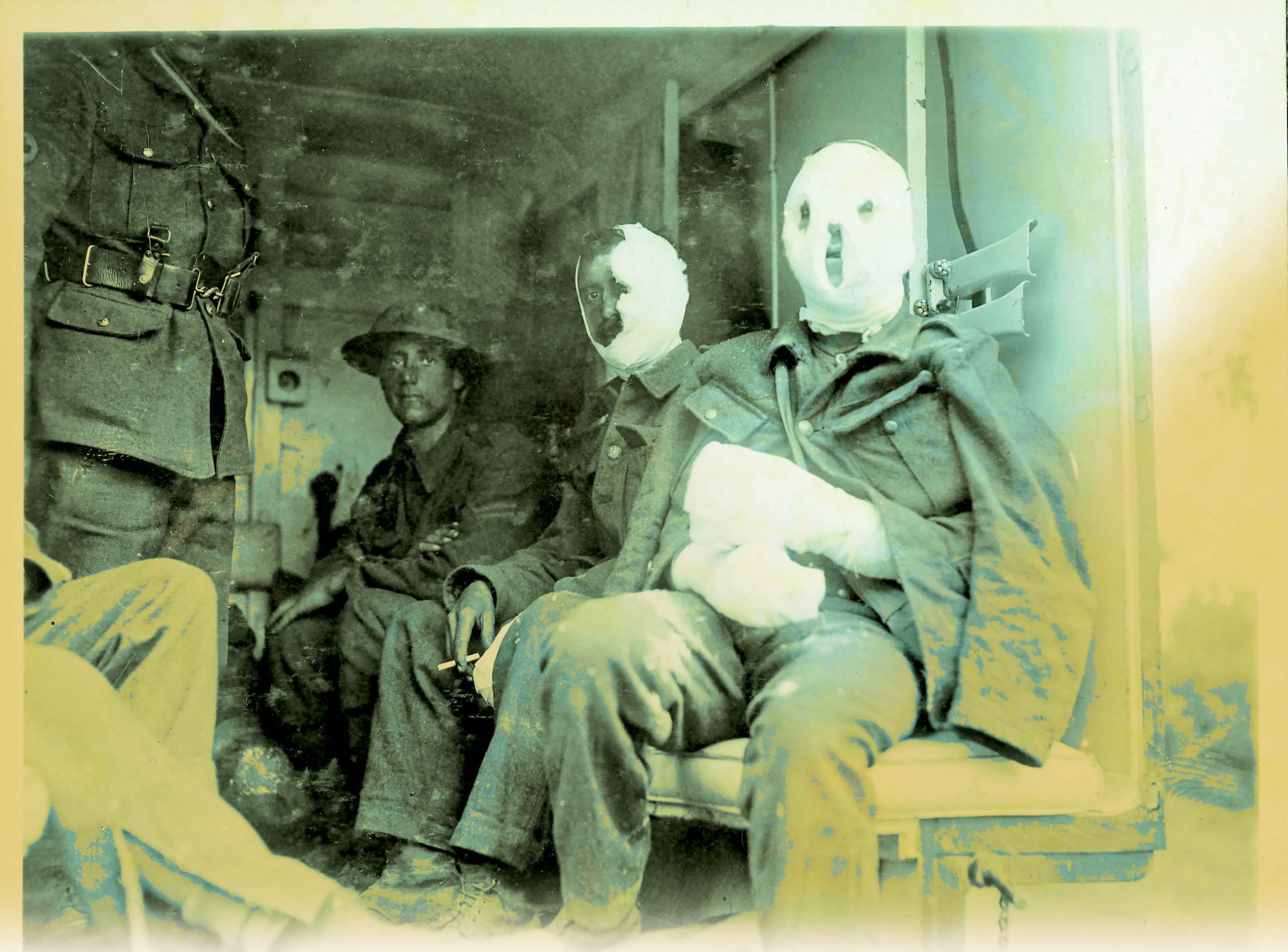

The mustard gas attacks caught the British soldiers unprepared. Within three weeks, there were some 14,000 casualties, about 500 of them lethal. Soldiers were initially unsure of what the gas was, as the vapours did not immediately burn the skin, throat and eyes like chlorine.

“It affects the eyes and nose, but not at first, so the men don’t put on their helmets till the damage is done,” wrote one Canadian medical surgeon.

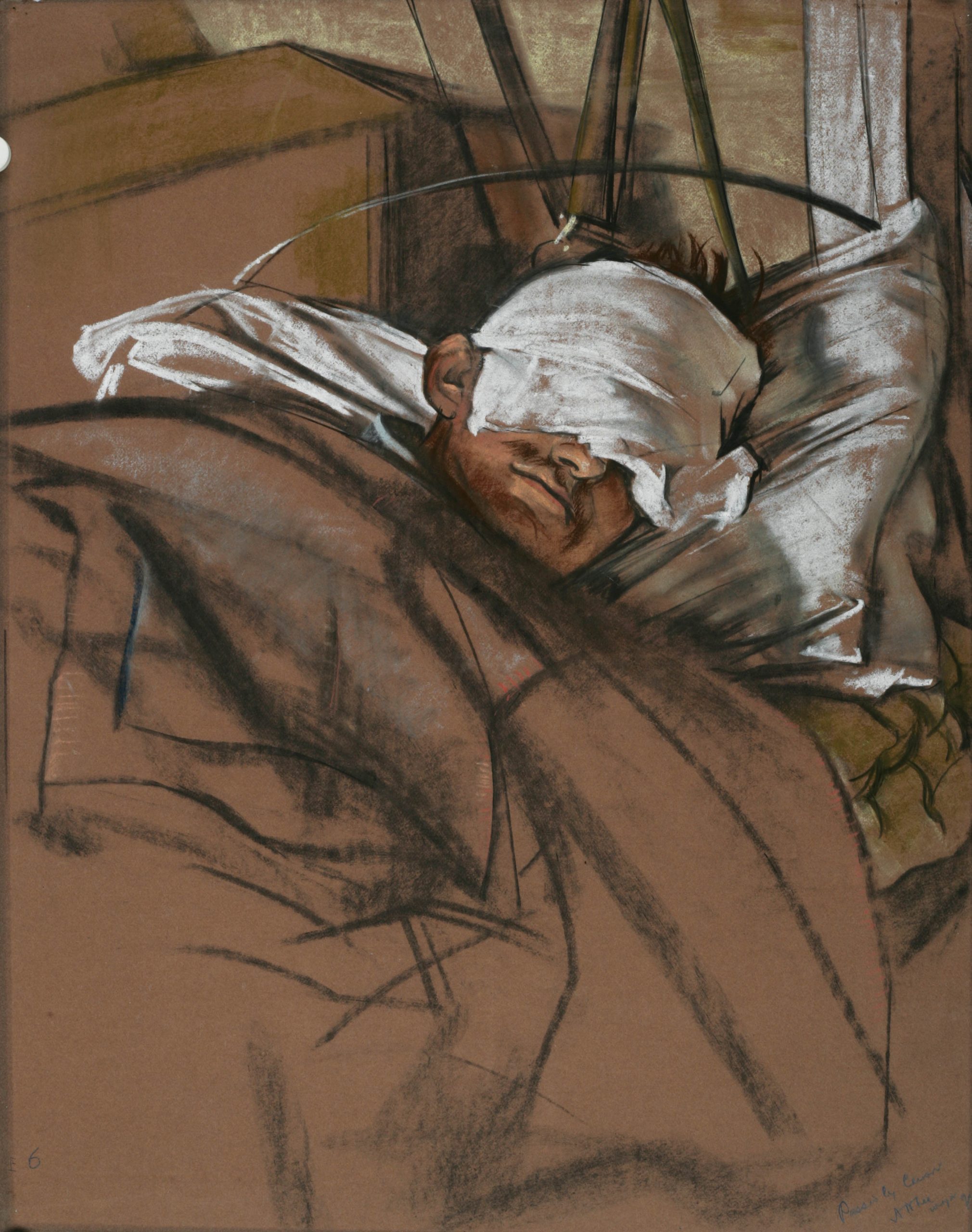

After a few hours, eyes became swollen and then shut, like a boxer after a fight. Exposed skin burned and blistered with ugly, pus-filled wounds that became infected in the mud. Even lightly poisoned men vomited relentlessly. In more serious cases, a hoarse cough set in, followed by blindness.

It was a terrifying thing to lose vision amid the mud of Passchendaele, where one step off a duckboard could lead to death by drowning in the mire. The blinded were led to the rear in long lines, hand on the shoulder of the man in front. The loss of vision was usually temporary, but some unlucky men were permanently blinded. On the second day, badly exposed soldiers began to die, their burned lungs unable to draw in breath.

“The vile mustard gas, that turned lungs to fluid and burned skin from the body, now permeated the light summer clothing, and the men writhed at the scorching touch,” one sufferer recounted.

“The mustard gas was certainly terrible stuff,” wrote James Johnston, a young Canadian transport driver. “I remember seeing a fellow die of it in hospital while I was there in Boulogne and it was hard to forget.”

Mustard gas was a persistent agent, unlike chlorine or phosgene, which rapidly lost potency in strong wind or rain. When the clouds of mustard gas settled into the mud of the trenches and no man’s land, it could continue to burn and blind. Brushing exposed skin against the infected muck resulted in blisters.

The mud also stuck to boots and uniforms. When soldiers moved into the relative safety of a dugout, the warmth of a fire or of other bodies released more mustard gas fumes from the mud and those within the enclosed space were poisoned. There seemed little defence against the gas, and soldiers became fearful of the trenches and dugouts in which they took protection from shellfire.

Respirators protected lungs and eyes, but could not be worn all the time. In fact, soldiers hated wearing the claustrophobic masks that left them struggling to inhale filtered air. Early in the war, many men had refused to put them on, usually gunners who could not breathe properly during their labour-intensive work or machine-gunners who could not see their targets. But with gas being encountered so frequently by 1917, to not wear a respirator was to risk permanent injury or agonizing death.

The assault on Hill 70 aimed to overrun the enemy’s positions northwest of Lens, then hold them against counterattacks. The goal was to bleed the enemy white. If the Canadians could bite off this piece of territory, Currie knew his machine-gunners and riflemen would lay down a withering wall of steel the Germans would have to pass through at great cost.

The most formidable killer of the war was artillery fire, and Currie’s gunners would play an essential role in shelling the approaches the Germans would take over open ground. The two attacking infantry divisions would be supported by 204 18-pounders and 48 4.5-inch howitzers.

Those divisional guns were augmented by the corps-controlled guns. Colonel Andrew McNaughton was a skilled gunner who had been appointed counter-battery staff officer in February 1917 and had proven his worth at Vimy. He had 111 larger artillery pieces, ranging in size from 60-pounders to 9.2-inch howitzers, as well as a handful of super heavies—four 12-inch and one 15-inch howitzer—to pound the German guns opposite the Canadians.

The gunners would use a mixture of high explosive and shrapnel, as well as a supporting chemical bombardment, consisting of 8,000 rounds of phosgene. This was to be fired against the enemy batteries within a high explosive bombardment to “confuse the enemy and conceal the fact that gas” was present, according to one planning document.

Additional gas drums were projected into Lens by special gas companies of the Royal Engineers. Forty-six tonnes of gas descended on the Germans, and prisoners later reported at least 150 gas casualties.

“The infantry,” wrote one British gas specialist, “were scared stiff of our gas.”

The Germans, in turn, sought to make life miserable for the Canadian infantry. Heavy rain had delayed Currie’s operation, but some of the infantry units had already been marched forward to within range of enemy shellfire two weeks before the attack began on Aug. 15. The Germans fired daily chemical bombardments along the front and on the roads where gas fumes lay thick. This slowed traffic, harassed soldiers and caused casualties.

“Especially in the early hours of the morning,” wrote Lieutenant F.R. Darrow, a former banker from Tillsonburg, Ont. “I think that in one week we received the total production of the biggest gas factory in Germany.”

The Canadians took cover from the conventional artillery fire in shattered villages, but the gas seeped into dugouts, caves and basements.

“Shelling was almost continuous,” recounted Captain Harold McGill, medical officer of the 31st Battalion. “Our daily activities went on in an atmosphere of shell smoke, poison gas and brick dust.”

For hours every day, the Canadian soldiers wore their small box respirators. These were effective against gas except in very high concentrations, but debilitating to wear, reducing oxygen intake, making sleep nearly impossible and sapping morale.

“The one thing of which we constantly lived in fear was a gas attack,” wrote Alexander McClintock, an American who served with the 87th Battalion (Canadian Grenadier Guards). “I used to awaken in the middle of the night, in a cold sweat, dreaming that I heard the clatter and whistle-blowing all along the line which meant that the gas was coming.”

They were exhausted from chemical and conventional bombardments in the two weeks before the battle, but the Canadians summoned the strength to surge forward behind a creeping barrage at 4:25 a.m. on Aug. 15. They hugged the moving wall of shellfire as it tore its way over no man’s land and through the enemy trenches.

“As the barrage descended,” wrote Captain Robert Clements of the 25th Battalion, “all hell broke loose over the whole German forward area.”

The 1st and 2nd divisions fought through the enemy trenches and captured Hill 70, while the 4th Division to the south near Lens was the bait, drawing enemy fire. The battle was fierce and costly, but the Germans were driven back.

Having lost key terrain, the Kaiser’s forces reacted as Currie had expected: with an immediate series of counterattacks. Canadian riflemen, backed by Lewis and Vickers machine-gunners, were ready as the German soldiers left their trenches. The attackers were cut down

mercilessly. Canadian gunners poured more shells into the target-rich battlefield. An enemy counter-attack at 6 p.m. was destroyed by

the 1st Brigade, Canadian Field Artillery “with most gratifying results,” noted its war diary. It was a terrible slaughter.

The Germans attacked at least a dozen times on Aug. 15 and 16, and 21 times by the 18th. Some brave frontsoldaten made it to the Canadian lines, but they were killed or captured. The Canadian gunners continued to cause terrible carnage, firing tens of thousands of shells. “They were mowed down by our artillery and machine-gun barrage,” one divisional report noted.

By Aug. 17, the third day of the battle, the Germans realized they could not drive the Canadians off Hill 70 unless they knocked out the Canadian gunners. They turned to mustard gas.

In a 19-hour period from Aug. 17 to Aug. 18, German gunners fired more than 15,000 mustard gas shells into the Canadian lines, with a concentration around Hill 70. The batteries of the 1st and 2nd artillery brigades were heavily targeted, and the many gun pits there were under a haze of gas. Gunners choked behind their masks, barely able to see their shells or fuses. Then the Germans attacked again.

As lethal tendrils hovered in wisps around them, the gunners realized their comrades in the infantry needed protective shellfire. Gun crews took off their gas masks one by one to answer the increasing frantic calls coming in over the phone wire and signalled by emergency flares.

“Rather than slacken their fire or impair its accuracy while answering the SOS calls, many men removed at least the face-piece of their box respirators,” one official report noted. “Others were gassed while replenishing ammunition.”

The Germans made temporary advances through the now-slackened shellfire and drove into the line on the 2nd Division’s front. But as the Canadian gunners made their personal sacrifice, firing without respirators, the rate of fire increased, causing carnage among the German follow-on forces who were caught in no man’s land. More than 10,000 shells fell among the Germans and they retreated again, leaving behind many of their dead.

But the battle was not over. As the sun rose on Aug. 18, it warmed the gas in the mud, and the fumes choked and blinded the Canadians along the front. They developed burns and blisters, then went blind.

The gunners got the worst of it. The 1st Brigade, CFA, recorded 107 gas casualties in the course of the battle, a stark contrast to 33 casualties from shrapnel and high explosives. Thirty-six gunners with the 2nd Brigade, CFA, were gassed, while only 22 were wounded from conventional weapons. Trench mortar teams and gunners throughout the divisional column suffered another 183 gas casualties.

While the gun batteries on the 1st Division’s sector were the worst hit by the mustard gas, the entire front encountered it in high concentrations throughout Aug. 17-19. The unit war diaries do not often mention the chemical attacks, but casualty statistics, compiled after the battle and now held at Library and Archives Canada, provide evidence of significant gassing (see sidebar on page 53).

“Two thirds of the battalion was suffering from this gassing,” observed Private R.D. Roberts of the 46th Battalion. “And still they were in the line and no hope of getting any relief.”

His battalion recorded only 21 gas casualties, indicating perhaps that there were many minor gassings not serious enough to send soldiers back for medical care, or that the situation was so desperate that all who could hold a Lee-Enfield were kept in the line, even if they were hacking and vomiting.

“The whole area was saturated with German mustard gas. It was all too easy, particularly when moving at night, to fall into a mustard gas shell hole without knowing what it was,” wrote one Canadian infantryman. “When the blisters started to form a day or two later, they turned into messes of yellow running sores.”

“On the way out, we had to go through gas and shellfire, wearing respirators,” wrote Private Deward Barnes on Aug. 18, the day his 19th Battalion was pulled from the line. “I couldn’t stand the full mask over my face, just used the mouthpiece.”

The soldiers wearing respirators in the dark could see little, stumbling and falling in the mud. But beyond this annoyance, Barnes does not mention any other instances where gas affected his comrades. Nonetheless, the 19th Battalion lost 20 men to it.

The failure to highlight gas in the battalion and brigade war diaries was no conspiracy. The official reports also do not single out, for the most part, the specific types of enemy bombardment (by shells or estimated number of shells) or attempt to guess at the mass of small arms ammunition fired in a battle. Such is the nature of the surviving records, although some are more detailed than others.

But the numbers of Canadian injuries caused by gas noted in the casualty statistics reveals that it was employed consistently. Gas was responsible for more than 10 per cent of Canadian casualties (in the battle)—1,122 out of 9,198—although the fatality rate was very low—less than five per cent. But what the numbers don’t show is the fear and deep fatigue it triggered among the soldiers across the front.

Although the Canadians had been warned of the enemy’s use of mustard gas and had been equipped with respirators and chemically treated blankets to hang over dugout entrances, the highest losses came from the insidious nature of gas used against fixed positions, where soldiers in open trenches had few options for retreat and where the debilitating effect of the gas, which remained potent for days, was hard to avoid.

The crippling level of gas casualties to gunners in the 1st Division led to an investigation to determine if they were culpable of dereliction of duty or if they were poorly trained. No fault was found.

In fact, it was determined by the artillery and gas services’ investigators that the gunners who removed their respirators “were keenly alive to the dangers of a gas bombardment.” Nonetheless, they carried out their duties “with the full knowledge of the probable consequences.” The gunners did “what they thought was required of them at all costs.”

Currie even took time after the battle to write a letter of appreciation to Brigadier-General E.W.B. Morrison, the general officer commanding of the Canadian artillery, to be circulated to the gunners. Currie praised the artillery and said “the assaulting infantry maintain that the artillery preparation has never been more complete, that the support has never been better, and that the liaison has never been more perfect.”

By Aug. 20, Hill 70 was under Canadian control. On Aug. 21 and 23, two additional probing attacks into Lens took place, but were rebuffed in fierce battles.

Currie was preparing for an additional operation when he was ordered to the Passchendaele battlefield to re-energize that stalemated front. The Canadians had taken Hill 70 and held it against at least 21 counterattacks, but the Germans occupied Lens until 1918.

The slaughter of German troops was shocking; the battlefield was a carpet of corpses. First Army intelligence officers estimated enemy casualties at 12,000 to 15,000, but Currie believed it was around 20,000. It was never easy to measure German losses—often the enemy did not count minor casualties—but the Battle of Hill 70 was one of the few times on the Western Front when attacking forces inflicted more casualties on defenders than they suffered in turn.

The use of mustard gas at Hill 70 did not change the outcome of the battle. It just added to the misery of the soldiers at the front. The use of chemical weapons—especially mustard gas—would only increase throughout 1917 and into the final year of the war.

In 1918, more than a quarter of all shells fired by French, British, Canadian and German forces contained gas. Gas casualties also rose—from 7.2 per cent for the British in 1917 to 15 per cent in 1918. Canadian gas casualties totalled 11,572 during the entire war, although there were certainly thousands of additional cases not recorded or lumped in with losses to conventional weapons. Overall in the war, gas accounted for more than one million casualties.

“There was nothing more horrible than to see men dying from gas,” wrote Canon Frederick Scott, the much-loved poet and padre of the 1st Division. “Nothing could be done to relieve their suffering.”

The concept of chemical warfare hearkens back to the first poison-tipped arrow. But the scale of it in the First World War, despite Hague conventions forbidding “poison or poisoned weapons,” was unprecedented—and not seen since. While it killed and maimed, its most important purpose was to reduce morale, slow operations, and add to the desolation of those caught in the grip of this foul weapon.

Gas casualties by the numbers

1st Division suffered infantry losses of 3,351 in August 1917. The worst period was during the high intensity combat of Aug. 15 to 18, when gas accounted for 338 of the wounded and killed.

1st Battalion suffered 14 gas casualties on Aug. 18 and another seven men were lost to the after-effects the next day—likely from contaminated mud or lingering fumes.

4th Battalion was particularly hard hit, with gas causing 77 of its 190 casualties through the month. Thirty-nine of its soldiers succumbed to gas on Aug. 18.

14th Battalion lost 83 men to gas.

2nd Division was also swamped in gas, but its infantry losses were more limited, with about a dozen chemical casualties per unit in the month. This paled in comparison to the division’s total infantry losses of 2,914.

3rd Division, largely out of the line for the battle, was less exposed to the chemical cocktail swirling around, and its infantry divisions suffered only minor losses to gas in August. There were exceptions, however, such as the 50th Battalion, which had 388 killed and wounded, of which 69 were attributed to gas.

4th Division was evidently not the target of German gas. Despite its holding operation opposite Lens, it had minimal gas casualties. Some units, nevertheless, were badly doused, including the 75th Battalion, which lost 37 to gas, and the 102nd Battalion, which had 31 men sent to the rear with chemical burns.

Support units in the front lines, such as machine-gun companies, were also hard hit by gas. The 16 machine-gun companies listed 96 gas casualties from a total of 271 killed or wounded. The high casualty rate from gas was likely because the guns were not easily moved away from gas-polluted areas.

Lines of communication were also targeted and few units working along them—pioneers, labour and engineers—escaped unscathed.

From Aug. 15 to 25, the Canadians suffered 1,122 gas casualties, from a total of 9,198.

Advertisement