The most familiar images from the end of the war are the joyful and sometimes raucous VE-Day celebrations on May 8, 1945. But the war did not end all at once for everybody. Freedom came in stages as the Allied front crept forward across Europe.

Canadian liberators fought town to town, beginning in Sicily in July 1943, through France and Belgium with the D-Day invasion of June 6, 1944, and in the Netherlands from September 1944 to the unconditional German surrender on May 7, 1945.

Canadians on all fronts made poignant observations on the war—and its end. Some of their experiences are recounted here.

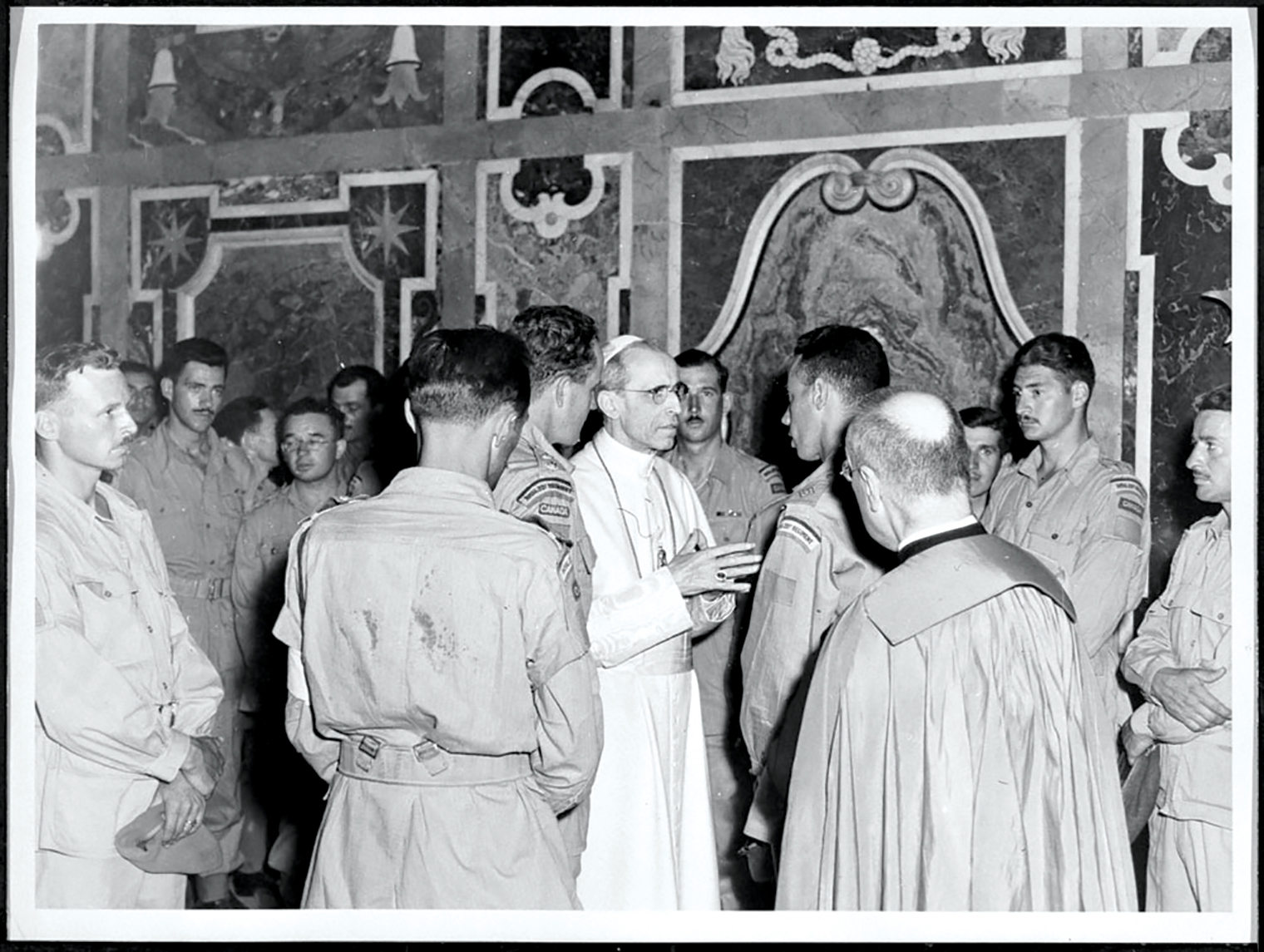

On leave in Italy

Rome fell to the United States army on June 4, 1944, and Canadian troops granted leave headed to the first liberated European capital.

“I was very lucky to get one of the first leaves in Rome, and they opened up a hotel just for the Canadians,” said gunner Douglas McDougall. “I wanted to see St. Peter’s [Basilica]. One of the Swiss Guards came up to me and said, ‘Would you like to have a private audience with the Pope?’” Pius XII had specifically asked to talk to Canadians. “I said, ‘Oh, that would be quite an honour.’ So he took me into this room and shortly, His Eminence came in and gave us a little blessing.”

A visit to Rome was a brief respite for Canadians who were not always warmly welcomed as they liberated town after town into 1945. “Belgium, France, Holland, they were all occupied, and they welcomed us,” said Alfred George Sellers. But Italy had been an ally of Germany. “People down in Italy sort of put up with us.”

Joy in France

“We said that at any cost we would take Dieppe,” said Indigenous veteran Hugh Victor Letendre in a Veterans Affairs Canada Heroes Remember video. “But you know, we never fired a shot.” The Germans had vacated the port city. Nevertheless, “we were a proud bunch of boys,” who marched in on Sept. 1, 1944.

Major Dennis Bult-Francis had been wounded in the Dieppe Raid in August 1942. He returned in 1944 with the 8th Reconnaissance Regiment and, as they entered the town, they were met by a storm of flowers.

It was impossible for the Canadians to keep marching forward in the dense crowd, and the parade was soon engulfed by local citizens anxious to share their hospitality. No Canadian paid for a drink or a meal, and many French people invited soldiers home to dinner, even though they themselves had been living on meagre rations.

On Sept. 3 came “the most impressive and meaningful Canadian parade of the war,” reported Canadian Press journalist Ross Munro, who had landed with the troops at Dieppe two years earlier.

After the victory parade, a ceremony was held at the graveyard where 850 Dieppe Raid dead lay. The graves were covered with flowers.

After Dieppe, the Canadians returned to the fight, liberating more French towns and cities.

“The wine of liberation had warmed every heart,” wrote Colonel C.P. Stacy in The Canadian Army at War—Canada’s Battle In Normandy. The French had “given themselves up to delirious joy; and the reception accorded to the forward troops, or to anybody in khaki who happened to be first to enter a village, was something to be remembered for a lifetime.”

Freedom in Belgium

Meanwhile, 300 kilometres to the northwest, Bill Tindall followed the troops who were chasing the Germans out of Brussels on Sept. 2, 1944.

“They kept on going and we stopped…the women are coming: ‘Vive les Canadiens!’” They smothered the men with kisses. “They thought we were the heroes…it just said ‘Canada’ on the sleeve of the army uniform. What the heck.”

“All through Belgium and France, they were pretty good to us all,” recalled Ken Parton of the 8th Reconnaissance Regiment. “And the girls were pretty good too.”

Early in the new year, after much fierce fighting, Belgium was freed from the Nazi yoke.

Elation in the Netherlands

Liberation crawled across the Netherlands. Maastricht in the south was liberated by the U.S. army on Sept. 14, 1944. SS occupiers on the North Sea island of Schiermonnikoog finally surrendered to Canadians on June 11, 1945, the last piece of Europe liberated from Axis occupation by the Allies.

The Dutch, who suffered thousands of deaths from starvation and cold during the Hunger Winter (see page 18), welcomed with open arms the soldiers who liberated them from nearly five years of brutal occupation.

“Aardenburg [in the southwest near the Belgian border] has a particularly sentimental memory for me, because my section of nine men were the first troops to enter that town,” recalled Al Notman of the 17th Duke of York’s Royal Canadian Hussars. “We stormed a house there and the Germans rushed out the back door. The coffee that they were drinking was still warm when we entered the house.”

After years of deprivation, the Dutch did not have much, but shared what they could, even if it was only good company.

Cliff Henry Lloyd was invited by a schoolteacher to a family dinner in Nijmegen. “You know what they had for dinner? Fried apples.” Lloyd shared his rations with the family and was invited along to a concert. “They were good to me.” When it came time for him to leave, the teacher and her sister “bicycled six miles out to say goodbye.”

At Sint-Oedenrode in December 1944, Charlie Fielding and his tank crew shared their rations, against orders, with children who “looked so hungry; their hair was falling out and their stomachs were swollen…. By the time we left there in a week, they were laughing.”

When he visited 16 years later, he was instantly recognized. “My family and I always remember you and your crew,” said one of the children, now an adult. “You brought us food when we were hungry and coal when we were cold. It was the best Christmas we ever had.”

Ted Sheppard was among liberators of the Westerbork transit camp on April 12, 1945.

“An elderly Jewish man climbed up onto my armoured car and all he wanted to do was touch my hand, it seemed,” said Sheppard. “Then he unpinned from his vest the yellow leather star…they were forced to wear. He took it off his jacket and he insisted I have it.” It was the only thing he had to give.

The Dutch people regained energy as airdrops of food enlivened liberation celebrations.

“I was surprised and frightened by the sound of gunfire [in Nijkerk],” wrote Felix Perry of the Prince Edward Highlanders in Red Soil! “Were we under attack? Had the Germans regrouped?”

But when he went into Nijkerk and saw people laughing and dancing, he realized Canadian soldiers had fired their rifles after news of the German surrender in Holland

on May 5, 1945.

“My Dutch ‘mother’ cooked as big a feast as she could with the meagre supplies available, and I broke out a bottle of black-market wine. We toasted the end of the war, the liberation of Holland and our friendship. I would never see them again.”

Harold Nahdin Young arrived in Nijmegen on May 8 to see thousands of people crowding the town centre. People danced and sang and kissed. Tracer bullets fired into the air looked like fireworks. Homemade fireworks, made from the cordite in artillery shells, would “take off like a rocket, and go scooting all around and then come down.”

In Arnhem, “the whole town just went berserk,” recalls Doug McDougall, who had been in Rome when the war ended there. “They pulled me out onto the street. I had a girl on one arm and another one on the other…and we all went dancing all the way down the street. Excitement!”

No elation in Germany

“We were one of the first to know officially it was over,” said Royal Hamilton Light Infantry signaller Sam Ross. He and some friends commandeered a German beer delivery truck. “I think that’s the only time I really got drunk in my life.”

In Oldenburg, “the whole world went crazy,” recalled Bob Grant of the 10th Armoured Regiment (The Fort Garry Horse) in Testaments of Honour: Personal Histories of Canada’s War Veterans by Blake Heathcote.

But among the Canadian soldiers he knew, “there was just no excitement at all. There was no elation. At the end of the war, there weren’t too many of us who’d landed on D-Day.”

In Marx on May 7, gunner James P. Brady and his unit had rousted out a German farm family who had used Russians as slave labourers.

“We permit them to use the bedroom of their former master, which gratifies our ironic spirit of revenge,” said Brady in Battle Lines by J.L. Granatstein and Norman Hillmer. The next day, VE-Day, “our crew are silent and thoughtful. Anti-climax…and quiet satisfaction that the job has been done and we can see Canada again.”

The former slaves revealed a secret liquor stock. “What a find. Our troop had a glorious binge,” said Brady.

“VE-Day, it was just another day for us,” recalled Andy Anderson of the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion in Testaments of Honour. “We were still dealing with the Russians, displaced persons, PoWs.” He recalled some armed Russians, “half of them drunk and out of control. They kept saying ‘Women, we want women.’ Almost every day, we’d find a civilian woman murdered or raped.

“That night, when things quieted down, it was the first time in a couple of years that I could really think about going home.” Comrades shared his view. “They didn’t want to get drunk or throw things around in the street; they just seriously thought about family for the first time.”

Still in danger at sea

For some, including the crew at sea on HMCS Lasalle, the end of the war in Europe was just another day of duty.

“We had to stay out in case some of those German submarines didn’t get notified that the war had ended with Germany,” recalled Walter Jacuk.

“VE-Day was very low key,” said Rex Rose, who was on duty in the English Channel. “We could see the fireworks going off on the English coast as we were going down the channel.” As the ship refuelled, “we heard all the big deal, wonderful celebrations.”

In Londonderry, Northern Ireland, four U-boats were tied up after surrendering. The German crews hadn’t yet been taken off.

“You think to yourself, ‘I wonder if they ever had us in their periscope sight? Did we ever drop depth charges near those people?’” said Rose.

In Quebec City, merchant mariner Tom McCulloch recalled his ship’s small guns firing in celebration; in Halifax, newly commissioned Bill Black came back aboard HMCS Annapolis to find fellow officers had hauled his pyjama bottoms up the yardarm.

Robert MacLean, who served aboard HMS Devonshire, was in Oslo, Norway.

“The population was ecstatic,” he said. “I recall that they had two parades, one day half the population got out and marched in front of the other half and then the other half got out the second day and marched in front of the first half.”

The war had ended, but he was still in danger. “Quislings [Norwegian Nazi collaborators] were…shooting indiscriminately at people.”

Active in the air

“We were still active right up to the last of the war,” said pilot Donald Murchie, who was with 412 Fighter Squadron, RCAF, stationed in Munster, Germany.

On April 25, 1945, No. 6 Group, RCAF, contributed 192 aircraft to the final bombing raid in Europe, on the island of Wangerooge in Germany’s Frisian Islands.

Among them was a Canadian-built Avro Lancaster, nicknamed X-terminator. Only one aircraft was shot down, gunner Don McTaggart recalls on the Bomber Command Museum of Canada website. But he watched bodies of crew fall into the sea after two Halifaxes and two Lancasters collided.

VE-Day saw RCAF members celebrating in places as far apart as England and India. In London’s Trafalgar Square, Ralph Whitney Merkley encountered his brother, whom he hadn’t seen since he’d left home years before. In Madras, India, Frederick Lawrence Gray partied with navy and air force comrades.

In Munster, Germany, Canadian flyers had a proper celebration on VE-Day.

“They were popping champagne corks all over the place,” recalled Murchie. It was rare stuff too—1923, a vintage year. They’d had no qualms about raiding the bottles stashed in the cellars by Luftwaffe head Hermann Göering.

Celebrating in cities

“On VE-Day, London was chaos, just chaos,” said Hilda Ashwell, a decoder with the RCAF Women’s Division, quoted in Testaments of Honour. “You couldn’t move for people. Wall-to-wall people in Trafalgar Square and in front of Buckingham Palace, people singing and dancing and hollering in the streets.”

Army driver Barbara Chrisabel Wilson was chauffered down The Mall in London in Canadian General John Percival Montague’s car, his own driver having the day off and treating some friends to a real joyride.

Alexander M. Ross joined subdued VE-Day celebrations in Glasgow, Scotland. “The reaction of the half dozen locals in the bar was one of quiet acceptance—no cheers. Too many of the pint mugs in silver or pewter hanging behind the bar would never been taken down by the original owners,” wrote Ross in his memoir, Slow March to a Regiment.

Revelry in Canada

In Montreal, revellers couldn’t wait for VE-Day, and took to the streets on May 7 when the news broke. Anyone and everything that could make a noise did so. Breweries stopped deliveries for the day to avoid hijackings; liquor stores, bars and taverns were ordered to close. Churches and synagogues were crowded as people gave thanks for those expected home soon—or mourned for those never coming home again.

Downtown streets in cities and towns across Canada and Newfoundland were jammed building-to-building on VE-Day. In Moncton, N.B., people even stood atop buildings.

“We celebrated with a parade” in Fredericton, recalled Joyce Fortune of the Canadian Women’s Army Corps. “I felt good to hear about the end of the war in Europe because most of the people from around Blackville were in Europe.”

In Ottawa, “everyone was on the streets; it was a very beautiful day,” recalled Julienne Leury, formerly of the RCAF Women’s Division. But she was downcast. “I was disappointed about becoming a civilian again. I felt like my big adventure was over.”

“News came over the intercom in an algebra class—without any permission, we all left the classroom and headed for Parliament Hill; so crowded we could hardly move; the carillon played nonstop,” recalled Florence Stoodley Berndt in a Canada Remembers Facebook post.

In Toronto, “VE-Day burst upon us a rising tide of excitement and expectation,” Peggy Bates wrote to her husband Captain Pat Bates, who was recovering overseas from wounds. “I felt like walking on my hands…. Bells rang all over the place and sirens whined and flights of planes zoomed over and all sorts of jalopies strangely decorated whizzed through the streets filled with shouting kids. Racks of flags broke out everywhere…. Toronto celebrated in a glad and orderly way…certainly none of the Halifax hooliganism.” (See page 38.)

VE-Day celebrations in Calgary were capped off by a downtown barnstorming by a Mosquito piloted by J. Maurice W. Briggs. Employees in the Hudson’s Bay store saw the plane “streaking past their windows at over 300 mph,” says an article by Richard de Boer on the Bomber Command Museum website.

Briggs flew under a trestle spanning 9th Avenue, and barely missed the flagpole atop the 11 storeys of the Palliser Hotel. Sadly, Briggs crashed the next day at the Calgary airport.

Air-raid sirens at 7 a.m. on May 7 brought news of the end of the war in Vancouver. Within an hour, buildings were festooned with bunting and paper streamers. In Victoria, George F. Lowe captured an amateur movie of the victory parade, after which the wide streets were completely filled by the crowd of thousands, who decamped in Beacon Hill Park for a service of thanksgiving.

No one wants the honour

On May 5, George Blackburn witnessed rounds of red, white and blue smoke fired at 8 a.m., the beginning of the ceasefire, “the last rounds fired on the Western Front in the Second World War,” he wrote in The Guns of Victory. He had heard just the day before that Hitler was dead.

“There are no boisterous victory celebrations,” he wrote. “It is enough to relish the deep relief and gratitude that the fighting is over and you have survived [despite] the growing anxiety that you may get it just before it’s over.”

That was a sentiment shared by tank crewman Roy Lane in his memoir, Chariots of Iron: “For us, there was no celebration, just a great feeling of relief that the killing and being killed was over…. No one wanted the honour of being the last one killed.”

Advertisement