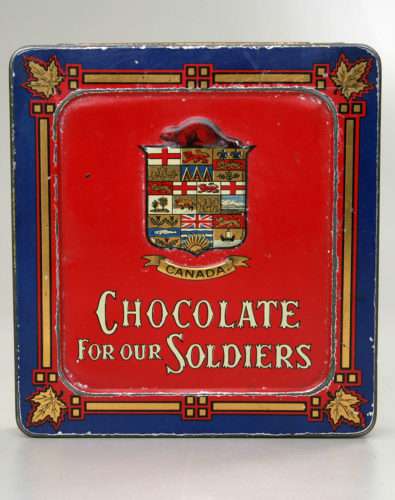

A chocolate tin produced by The Cowan Chocolate Company of Canada in Toronto and marketed in retail stores across the country during the war years. Filled with the company’s famous “Maple Buds,” milk medallions or chocolate ginger, many found their way to the front lines. [Fanshawe Pioneer Viillage]

Rwanda was embroiled in civil war; it was on the verge of a genocide. Yet it would be months before the contingent under Dallaire’s command would reach the 2,548 troops authorized by the UN and, even then, it wasn’t enough.

The general stepped out of his vehicle to find one of the child soldiers running toward him, AK-47 in hand. The next thing he knew, the barrel of the Soviet-made assault rifle was up his nostril. The kid looked about 13.

“His eyeballs were huge, he was sweating, all the kids all around screaming and yelling, and his hand’s on the trigger,” said Dallaire, now a leading advocate for children forced into military service around the world.

As Dallaire pulled the chocolate bar from his pocket, he gently pushed the rifle barrel away from his face.

“An adult you can sense, you know, where you’re going with it. A child you can’t, and if they’re able to get that close you don’t know what might make him pull the trigger. What is so chilling is that a child is totally unpredictable.”

The boy’s compatriots were goading him on, urging him to shoot. Dallaire had no training or experience in defusing such a volatile situation. No one did at the time. But he did have a chocolate bar.

So the veteran soldier slowly reached into the breast pocket of his vest, his eyes locked on the wide-eyed young fighter who followed his every movement.

As Dallaire pulled the chocolate bar from his pocket, he gently pushed the rifle barrel away from his face and handed the undernourished boy the treat. The general, as they say, lived to fight another day.

A Nestlé ad promoting the company’s role in providing the military with Type D military chocolate rations. [Western Connecticut State University Archive]

During the French and Indian War (1754-1763), Benjamin Franklin was a quartermaster procuring supplies for British troops. He requisitioned six pounds of hard-to-get chocolate per officer as a form of compensation.

By the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783), foot soldiers were being issued chocolate rations, occasionally in lieu of payment. It was even considered a medical supply, so valued that in 1780, Dr. James Mann, a Continental Army surgeon, sent a desperate letter to the military hospital in Danbury, Connecticut, requesting a “pound of chocolate for the use of the wounded men at this place.”

The combined kick its blend of caffeine and sugar provides was valued into the American Civil War (1861-1865) and beyond.

As many as 80,000 of the tins were adorned with the royal visage.

Canadian and other empire soldiers fighting the Second Boer War at the turn of the 20th century were sent commemorative tins of chocolate by Queen Victoria herself. The tins containing a pound of chocolate. As many as 80,000 of them were adorned with the royal visage and inscribed with “South Africa, 1900” and “I wish you a happy New Year, Victoria RI.”

“I have just received a box of chocolate, Her Majesty’s present to the South African soldiers,” wrote Canadian Private C. Jackson to his father in December 1899. “There is such a demand for them by the officers and everybody else, as mementos.

“In fact I have been offered five pounds for mine, and at the Cape as much as 10 pounds is being paid.”

Cadbury UK told the Australian Broadcasting Corp. in December 2020 that the initial request from Buckingham Palace was “to be paid for out of [Queen Victoria’s] private purse.”

“The cocoa must be made into a paste and sweetened ready for use under the rough and ready conditions of camp life—the tins to be specially made and decorated,” said a period memo from Cadbury Brothers, notable pacifists who at first declined the job, then had to be talked into putting their name on the boxes.

“Ultimately,” said ABC, “the Palace won the diplomatic tug-of-war with Cadbury, as the Queen insisted that her troops know it was ‘good quality’ British chocolate.”

Chocolate was a staple of military rations during the First World War. During the famous Christmas Truce of 1914, Allied soldiers shared theirs with their German rivals while, in some areas, Germans sent chocolate cake into the Allied trenches.

In that heady first year of the world war, when everyone thought the fighting would end sooner than later, Princess Mary, the 17-year-old daughter of King George V and Queen Mary, organized a public appeal to raise funds to ensure “every Sailor afloat and every Soldier at the front” received a Christmas present.

The response was so overwhelming that the recipients were expanded to include every person “wearing the King’s uniform on Christmas Day 1914.”

The gift was a small brass tin, decoratively embossed with a portrait of Mary and the names of Britain’s allies. The contents varied: officers and men on active service received a pipe, a lighter, an ounce of tobacco and 20 cigarettes. Non-smokers and boys received a bullet pencil and a packet of sweets instead. East Indian troops often got sweets and spices and, best of all, nurses got chocolate.

The D Ration bar “was unappetizing and tough to chew.”

Years later, after Forrest E. Mars witnessed soldiers in the Spanish Civil War eating pellets of chocolate coated to keep them from melting in the sun, he developed M&Ms and patented them in 1941.

Rowntree of England had been producing “Chocolate Beans” since 1882, and renamed them Smarties in 1937. But M&Ms gained a hold on the Americans largely because they travelled well and withstood high temperatures.

The U.S. Army Quartermaster, Colonel Paul Logan, approached the Hershey Chocolate Co. in April 1937 to formulate an emergency chocolate ration bar to military standards: four ounces; high in food energy value; able to withstand high temperatures, and taste “a little better than a boiled potato” so as not to be overeaten. The ration provided 600 calories.

Hershey Tropical chocolate bars were included in American D rations. [stukasoverstalingrad.com]

Undaunted, the army also formulated the Tropical Bar to withstand tropical heat.

Chocolate was included in Red Cross packets to Allied prisoners of war, though they rarely made it past the camp guards.

“It is estimated that between 1940 and 1945, over 3 billion of the D Ration and Tropical Bars were produced and distributed to soldiers throughout the world,” Allison Carruth wrote in War Rations and the Food Politics of Late Modernism.

“In 1939, the Hershey plant was capable of producing 100,000 ration bars a day. By the end of World War II, the entire Hershey plant was producing ration bars at a rate of 24 million a week.”

The Hershey Chocolate Company was eventually issued the Army-Navy ‘E’ Award for Excellence for exceeding quality and quantity expectations in the production of the D ration and the Tropical Bar. Chocolate’s role in the war and the regard with which soldiers came to hold it extended into postwar life in North America and elsewhere.

The Tropical Bar remained standard ration for the U.S. military in Korea and Vietnam, part of a “Sundries” kit that also included toiletries before it was declared obsolete. The bar made a brief return aboard Apollo 15 in July 1971.

Canadian and other British Empire soldiers fighting the Second Boer War at the turn of the 20th century were sent commemorative tins of chocolate by Queen Victoria.

Canada’s Composite Ration Packs, or Compo Rations, included a block of chocolate in a tin. Dutch chocolate may be renowned, but many a Dutch child’s first taste of chocolate came by the hand of a Canadian soldier in 1944-45.

Tony Romeyn was five years old when Canadian troops flooded the streets of his native Haarlem, Netherlands, in the victorious summer of 1945.

“We never had candy,” the Prince George, B.C., resident told the Trail Times in May 2020. In fact, they hadn’t had much of anything for some time, surviving on boiled tulip bulbs and whatever else they could scrounge through the preceding Hunger Winter.

Sussie Cretier was just 10 when the Germans invaded in 1940. Her father, Willem, was a mechanic involved in the Dutch Resistance. He passed information to the Allies and hid Jews in their home until he was found out and the family was forced to escape behind the lines of the approaching Allies in the town of Alphen.

They had only the clothes on their backs, living day-to-day on whatever food they could gather, including the chocolate and chewing gum Bob Elliot and other Canadians gave Sussie to take home to her family.

For Christmas, the soldiers had a winter coat sewn for her from a grey army blanket; they plucked buttons from their own jackets to help finish it, and found her new shoes, along with a sweater, scarf and pants.

Elliot kept in touch with the Cretier family over the years. In 1981, he paid them a visit. He and Sussie fell in love, married and moved back to Edmonton. The coat is now in the collection of the Canadian War Museum.

A touching scene from the series “Band of Brothers,” based on the Stephen E. Ambrose book of the same name, depicts a Dutch child’s first taste of chocolate. [Playtone]

The healing powers of chocolate extended into Germany, where young Joachim (John) Zinram and his family in Koblenz were forced from their home by Allied bombs. American troops were stationed near their town after the war ended.

“It was a very sad time; we had nothing to eat,” Koblenz told a U.S. Army reporter in Wiesbaden last June. “Every day, I took an empty lunchbox with me to school.

“During lunch, it was filled with either grits, rice pudding or just chocolate milk,” which the school received from the Cooperative for American Remittances to Europe (CARE) packages. “It meant the world to us; it helped us survive.”

“Many soldiers stopped their vehicles and gave candy, chocolate and bubble gum to us children.”

It surprised Koblenz that the Allied soldiers no longer viewed the Germans as their enemies and helped them rebuild their shattered country.

“The best memory I have of the Americans back then was when they drove their tanks and jeeps through the streets of our town. I always heard them long before they got there, and then I stood patiently on the side of the road, waving to them.

“Many soldiers stopped their vehicles and gave candy, chocolate and bubble gum to us children. We were in awe—these were like treasures to us.”

The Desert Bar was a short-lived attempt by Hershey to dispense with surplus product after the Gulf War. [wikimedia]

During the Gulf War in 1990-91, Hershey shipped 144,000 of the bars to American soldiers in the southwest Asia theatre, but the response was temperate, at best.

With the war over before the balance of supply could be moved, Hershey packaged the remainder of the production run in a “desert camo” wrapper, dubbed it the Desert Bar and marketed it to the public.

The product was short-lived.

Advertisement