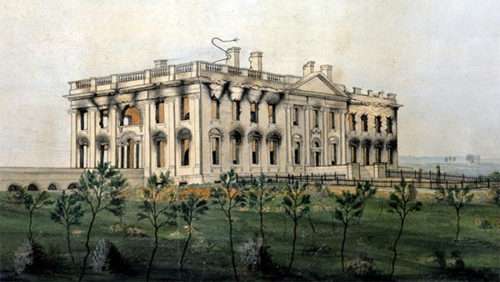

“The President’s House,” a watercolour by George Munger, shows fire and smoke damage caused by British forces on Aug. 24, 1814. [George Munger]

It was August 1814. In a few months, the war would be over. But now the American capital was in a frenzy. British troops were gathering on the horizon and the Battle of Washington was about to begin.

Before leaving to monitor military operations, America’s fourth president, James Madison, had asked his wife Dolley if she had the “courage or firmness” to stay put at what was then called the Presidential Mansion until he returned. He asked her to gather important papers and be prepared to abandon their stately home at any moment.

Dolley Madison crossed the Potomac River and found sanctuary in northern Virginia.

And so Dolley Madison began securing what treasures she could in the residence occupied by American presidents since 1800. She couldn’t take everything, but there was one thing that absolutely had to come.

“Save that picture!” she ordered, gesturing toward a full-length, eight-by-five-foot portrait Gilbert Stuart had painted of George Washington in 1796.

“Save that picture if possible. If not possible, destroy it. Under no circumstances allow it to fall into the hands of the British!”

The title “First Lady” had not yet been coined. But Dolley Madison was no shrinking violet. She had become a catalyst in the Washington social scene and set a standard for those women who followed her into what would become known as the White House.

A portrait of James Madison by American artist John Vanderlyn was created in 1816, toward the end of Madison’s presidency. [White House Historical Association]

“It is done, and the precious portrait placed in the hands of two gentlemen from New York for safe keeping. On handing the canvas to the gentlemen in question, Messrs. Barker and Depeyster, Mr. Sioussat cautioned them against rolling it up, saying that it would destroy the portrait. He was moved to this because Mr. Barker started to roll it up for greater convenience for carrying.”

The president’s personal slave, Paul Jennings, was 15 when he witnessed the events of that night. Long after purchasing his freedom from the widowed Mrs. Madison, he wrote a memoir in 1865, reporting that it was Jean Pierre Sioussat, the French doorkeeper, and gardener John McGraw who took down the piece and sent it off on a wagon with some large silver urns and other valuables.

The painting was moved flat. It wasn’t until later that it was found to be a copy.

“Now, dear sister,” wrote Dolley, “I must leave this house, or the retreating army will make me a prisoner in it by filling up the road I am directed to take.”

Dolley Madison secured valuables from the executive mansion before the British arrived. [Gift of Thomas Jefferson Bryan/New York Historical Society]

Even as she made her escape on that night of Aug. 24, 1814, Major General Robert Ross was leading 4,500 British troops into Washington, setting fire to multiple government and military buildings, including the White House and the Capitol.

The attack has long been billed as retaliation for the recent destruction of Port Dover in Upper Canada and the burning and looting of York (now Toronto), which was then the capital of Upper Canada, the year before.

They said British troops were ransacking private homes, businesses and other buildings.

But in June 2013, the Washington Post reported that “the earlier arson of parliament buildings in York was not raised as a justification until months later, after the British faced criticism at home and abroad for burning buildings in Washington.”

Until that point, the newspaper reported, the British had filed complaints only about the “wanton destruction” along the Niagara region and Lake Erie, including Port Dover the previous May.

The attack and subsequent 26-hour occupation of the U.S. capital was the brainchild of Vice-Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane, who had been appointed commander-in-chief of the Royal Navy’s North America and West Indies stations, based in Halifax and Bermuda, respectively.

He ordered his commanders to “deter the enemy from a repetition of similar outrages.”

“You are hereby required and directed to destroy and lay waste such towns and districts as you may find assailable.… You will spare merely the lives of the unarmed inhabitants of the United States.”

As Ross and Rear Admiral George Cockburn, commander of the Royal Navy squadron in Chesapeake Bay, surveyed the night’s events, older women and elderly clergymen with women and children in tow confronted them requesting protection from abuse and robbery by British enlisted personnel.

They said British troops were ransacking private homes, businesses and other buildings. Ross had two soldiers put in chains for violating his general order.

A portrait of George Washington, painted by Gilbert Stuart in 1796, depicts the 64-year-old president near the end of his term in office. [Gilbert Stuart/Wikimedia]

As the seat of government and the most impressive building in Washington, the Capitol was a prime target for the British invaders. Before setting it on fire, they looted the building, which then included the Library of Congress and the Supreme Court.

Among the seized documents was a ledger entitled “An account of the receipts and expenditures of the United States for the year 1810.” Cockburn wrote inside that it was “taken in President’s room in the Capitol, at the destruction of that building by the British, on the capture of Washington, 24th August, 1814.”

He eventually gave it to his older brother Sir James Cockburn, the governor of Bermuda. The book was returned to the Library of Congress in 1940.

The British intended to burn the building to the ground. They set fire to the south wing first. The flames spread so quickly the troops couldn’t gather enough wood to burn the stone walls completely. However, the contents of the Library of Congress in the north wing helped with the job. Indeed, the library itself was wiped out, its 3,000-volume collection destroyed along with its neoclassical columns, pediments and sculptures.

The wooden ceilings and floors burned. The intense heat melted the glass skylights. The House rotunda, the east lobby, the staircases and the Senate entrance hall’s famous corn-cob columns all survived.

The Superintendent of the Public Buildings of the City of Washington, Thomas Munroe, valued the Capitol losses alone at $787,163.28.

Thomas Jefferson was moved to donate books from his own personal library to help rebuild the collection. They still form the basis of the Library of Congress holdings across the three buildings that make up its campus.

The British burning of Washington painting by Paul de Thoyras. [Wikimedia]

The “storm that saved Washington” did the opposite, say some. The rains sizzled and cracked the already charred walls of the White House and ripped away at structures the British had no plans to destroy, including the Patent Office.

The arsenal, dockyard, treasury, war office, even the bridge over the Potomac along with a frigate and a sloop were also destroyed.

A separate British force also captured Alexandria on the south side of the Potomac River that night. The mayor talked the raiders out of burning the town.

President Madison, military officials and his government had evacuated the city and found refuge in Brookeville, a small town in Montgomery County, Maryland. Madison spent the night in the house of Quaker Caleb Bentley, known today as the Madison House.

The president and his wife reunited and returned to Washington to find scorched facades on virtually all the city’s public buildings. The couple took up residence in a local home until the executive mansion could be restored.

It would be here that Madison learned of the successful negotiations of the Treaty of Ghent, which ended the War of 1812 on Dec. 24, 1814. The Madisons would not return to the executive mansion before he finished his two terms as president.

The United States Capitol after the burning of Washington, D.C. in the War of 1812. [Wikimedia]

It was, after all, seen as a war of American aggression, albeit inspired by British interference in American trade with France, its support of Indian resistance to westward expansion, and the Royal Navy’s bull-dogged insistence on continuing the practice of pressing American sailors into service aboard its ships (they were deserters, the British insisted).

“A free trade and sailors’ rights,” was the rallying cry of the Americans entering the War of 1812.

According to popular myth, the White House was first painted white to cover the scorch marks left after the British attack. The White House official history, however, says the building first gained a lime-based whitewash in 1798 to protect the exterior stone from moisture and cracking during winter freezes.

The “storm that saved Washington” did the opposite.

The term “White House” was occasionally used before the War of 1812, with the phrase appearing in newspapers in the first decade of the 19th century. President Theodore Roosevelt officially gave it the title in 1901 to distinguish it from the “executive mansions” that existed in nearly every U.S. state.

Congress did not sit for more than three weeks after the attack. When it did, some members wanted the seat of government moved to Philadelphia. Local property owners donated money to ensure that it didn’t.

It took 12 years to rebuild the Capitol. James Hoban, the White House’s original architect, was commissioned to lead the rebuilding of the presidential residence. The building was completed in 1817 and President James Monroe moved in.

President Harry Truman commissioned a major reconstruction of the decrepit building between 1949 and 1952.

In 2009, President Barack Obama held a White House ceremony honouring Madison’s former slave, Paul Jennings. A dozen Jennings descendants attended. The copy of the Washington portrait was on display in the East Room.

Advertisement