Do YOU qualify for disability coverage or a pension? Tips on eligibility, applying, coverage and MUCH MORE!

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- Inspired by the original charter

- How RCMP members fare

- Filling in the forms

- Educational assistance for veterans’ families

- Using skills and education to make the transition

- A long way to go (Survey Results)

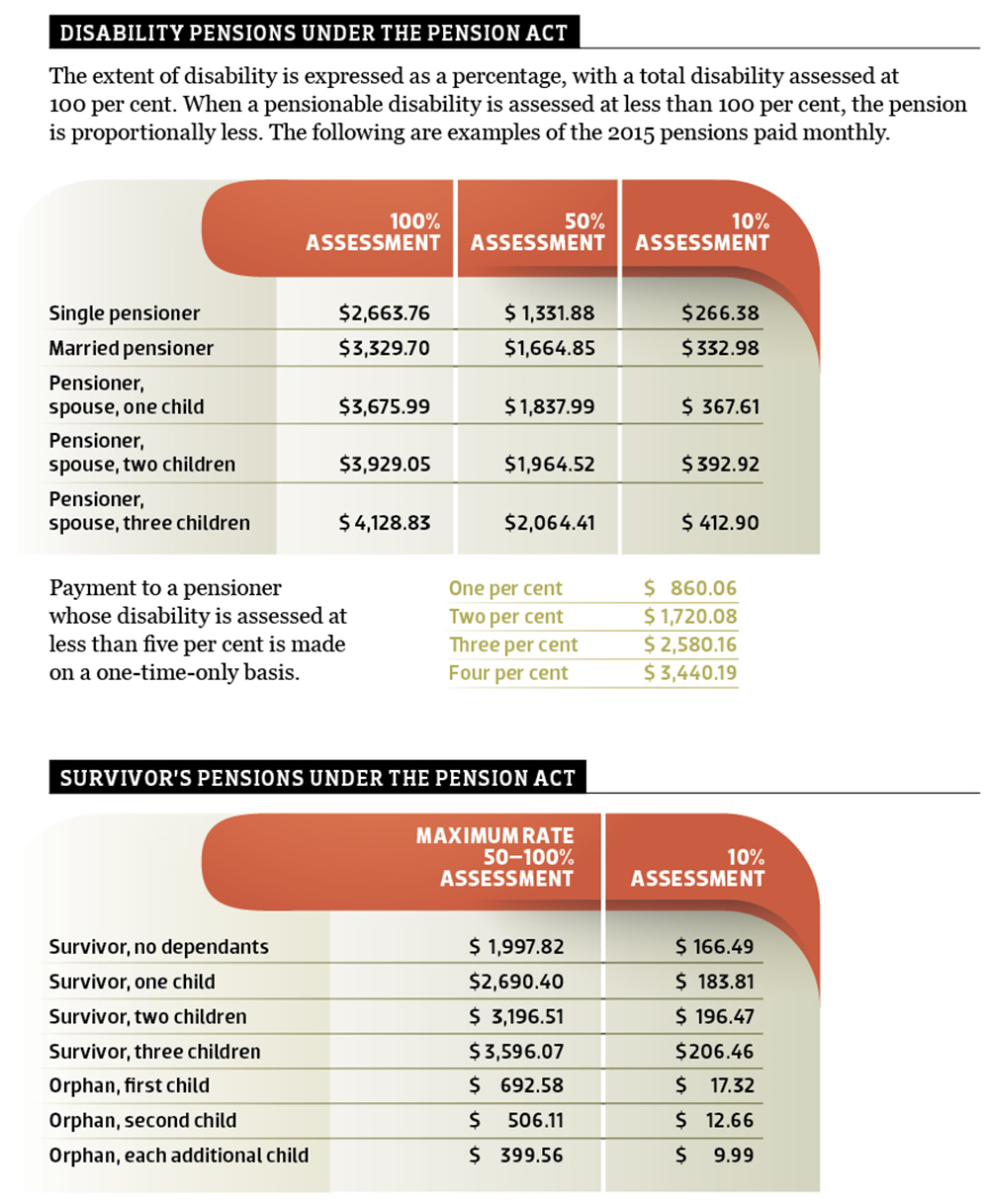

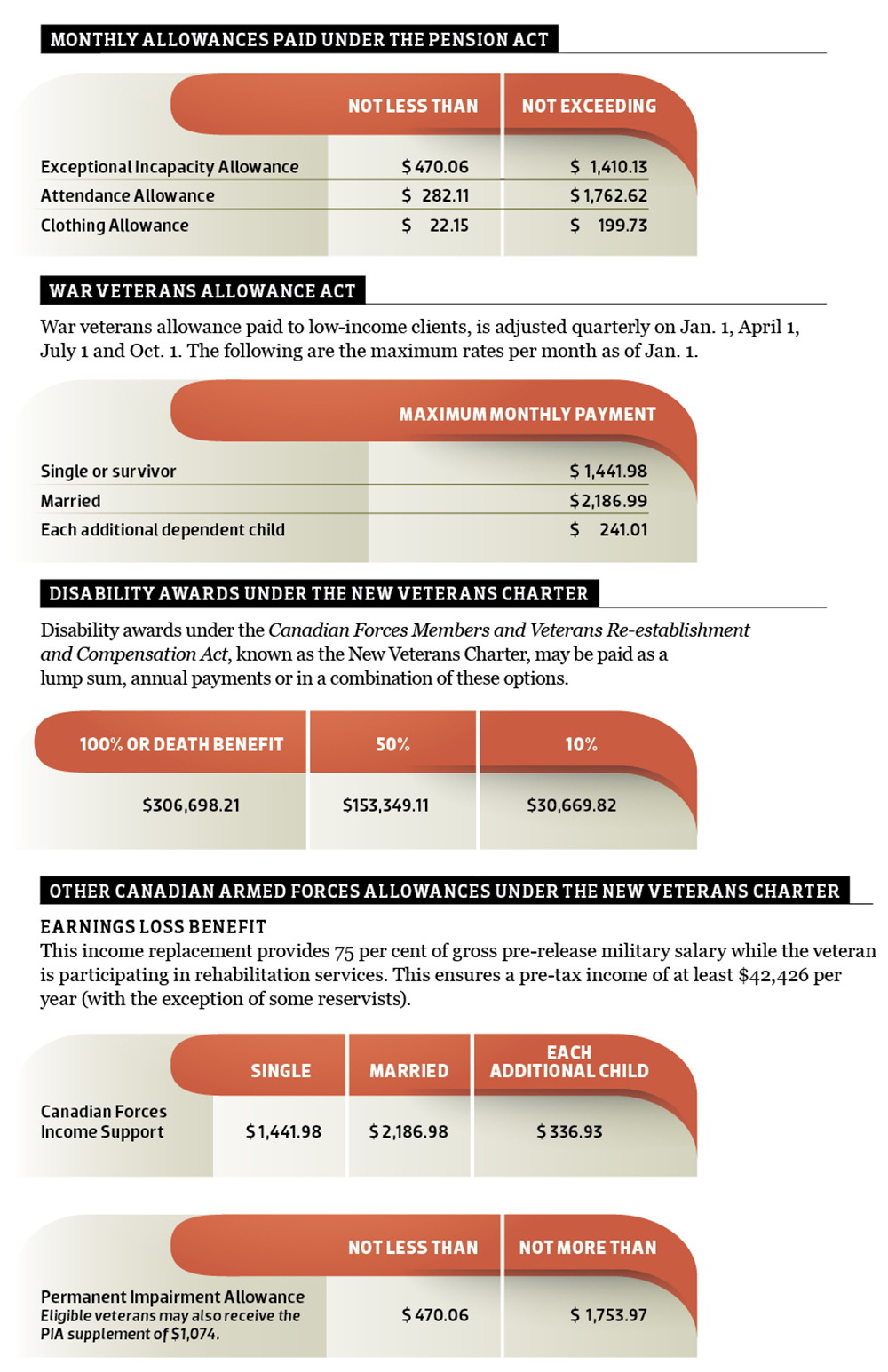

- Pensions, awards, allowances for 2015

- Frequently Used Terms

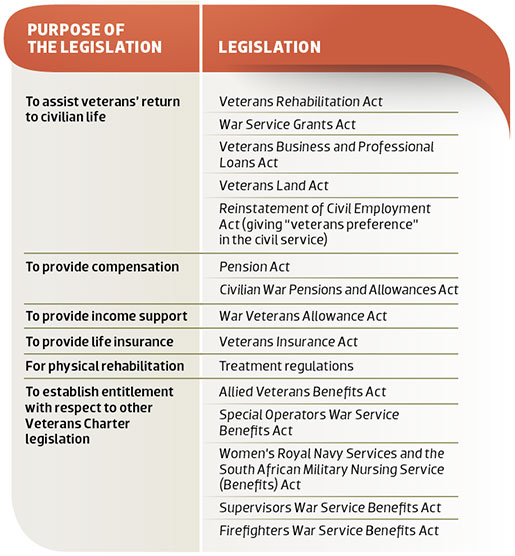

Inspired by the original charter

by Tom MacGregor

Shortly before Canadian troops began the attack on Vimy Ridge in April 1917, Prime Minister Robert Borden told them, “The government and the country will consider it their first duty to see that a proper appreciation of your effort and of your courage is brought to the notice of people at home that no man, whether he goes back or whether he remains in Flanders, will have just cause to reproach the government for having broken faith with the men who won and the men who died.”

Living up to that promise turned out to be a more difficult matter than expected. Out of a country with fewer that 7.8 million, 620,000 men and women signed up to fight for King and country. Of them, 66,600 were killed and more than 172,000 were wounded. At war’s end, the country was flooded with men seeking jobs when jobs were hard to find.

The only support for veterans and their families at the beginning of the war was a patchwork of pensions and charities. As the men, healthy and wounded, began returning home, veterans groups formed across the country bent on making sure the government lived up to the prime minister’s promise. Foremost in leading that charge was the Great War Veterans Association, which eventually merged with other veterans groups to form what today is The Royal Canadian Legion.

Their efforts and the general public’s support led to the passing of the Pension Act, which provided pensions to those who came back disabled, and a system of veterans’ hospitals across the country, providing much-needed medical care.

Still, finding a job and making that transition to civilian life was not that easy as Canada’s economy slowly changed from one based on agriculture to one based on industry.

It was a different story in the Second World War. Many veterans of the First World War were part of the federal civil service in Ottawa and the Legion and other groups were organized to have a strong voice. That led to a suite of veterans legislation which collectively was called the Veterans Charter.

Much of the legislation was aimed at giving an able-bodied veteran a reasonable start in life. There was the Veterans Land Act, which provided land to veterans willing to establish a farm or fishing business. The Reinstatement of Civil Employment Act gave “veterans preference” to returning sailors, soldiers and airmen and airwomen when it came to hiring within the civil service of Canada.

“I struggled through the system. I did not know where to get assistance when I was applying for benefits 30 years ago.”

For those who came back disabled from their service, there was the Pension Act, originally introduced after the First World War, and for those who could not make a go of things when they returned, there was the War Veterans Allowance Act to provide funds for the needy.

The mission was clear. The Veterans Charter was to provide opportunity with security for those who had made a commitment to serve the country in wartime. As Veterans Affairs Minister Ian Mackenzie said in 1947, “Not for 10, perhaps 20, years will it be known how much ex-servicemen and ex-servicewomen have been able to contribute to a Canada at peace as a result of these re-establish-ment measures.… When that accounting is made, I know the program laid down in the Veterans Charter will appear in true perspective as a social investment of unmatched success.”

Simply put, this suite of 14 acts of Parliament helps Canadians help themselves.

The research paper, The Origins And Evolution of Veterans Benefits In Canada 1914–2004, by the Veterans Affairs Canada–Canadian Forces Advisory Council (VAC–CFAC) states, “Canada’s evolving program for its Second World War veterans had a clear purpose: to build morale for the war effort and ensure a smooth and constructive transition to peacetime conditions once victory was won. It had clear goals: to look after those who could not be expected to look after themselves while preparing the able-bodied for work in the market economy through the philosophy of ‘opportunity with security,’ a concept that respected the basic social and economic realities of the country.”

These measures were modified over the years to accommodate Newfoundland veterans when the province joined Confederation in 1949 and the Korean War veterans. As the First World War veterans aged and the Second World War veterans caught up to them, Veterans Affairs Canada changed. Its federally run hospitals were dealing with patients who needed chronic and long-term care. The hospitals were gradually transferred to provincial control.

The new programs it developed were aimed at the aging veteran population and programs such as the Veterans Independence Program (VIP) were designed to help the aging veteran to stay at home.

Under the Pension Act, pensions had come to serve a number of purposes: income support, compensation for pain and suffering, and a gateway to other benefits and programs, such as VIP and long-term health care.

As the years passed, Veterans Affairs clients from the current Canadian Armed Forces increased but dissatisfaction was growing. In 2000, VAC released a discussion paper called, “Sir, Am I A Veteran?”, saying: “At Veterans Affairs Canada, veterans enjoy a privileged status. They are regarded as heroes and are, in effect, put on a pedestal.… On the other hand, members of the Canadian Armed Forces are not regarded as veterans with the result that they are not afforded the hero status conveyed through the veteran designation.… From the program and benefit perspective, there is no doubt that VAC looks after wartime veterans better than it does today’s members of the Canadian Armed Forces. There is a perception that weak pension claims from World War II veterans are more likely to be ruled on favourably than those submitted by Canadian Armed Forces members. CAF clients feel that they have to provide proof beyond a reasonable doubt in submitting pension claims, instead of being afforded the benefit of the doubt.”

In reaction to that and other reports, the VAC–CFAC Council was formed, chaired by Western University professor Peter Neary and including members of the military, VAC, veterans organizations and health professionals. Their work led to the New Veterans Charter (NVC) in 2006. The Royal Canadian Legion was represented by former lieutenant-general Lou Cuppens.

As the council found over the years after the Second World War, “The relationship of Canadian Forces veterans and Veterans Affairs was confined to limited use of the Pension Act. This eventually produced adverse consequences which have not yet been fully addressed. Although all the statutes relating to the Veterans Charter remained on the books, Veterans Affairs Canada did not concern itself with the rehabilitation and re-establishment of former members of the Canadian Armed Forces. The forces themselves eventually produced programs to fill some of this gap, but this was not the main business of National Defence. While the need for rehabilitation and re-establishment benefits continued, the government’s commitment to deliver these through Veterans Affairs atrophied.”

The council recommended a new approach, which after two years of planning led to new legislation and a variety of programs inspired by the original Veterans Charter.

Officially, The Canadian Forces Members and Veterans Re-establishment and Compensation Act, known as the New Veterans Charter, was a new approach to wellness for the Canadian veteran. Instead of the existing system designed to compensate for disability and create a gateway to other health benefits, the NVC is a suite of compensation and rehabilitation programs not for those who had signed up during wartime but for those who had chosen a career in the Canadian Armed Forces. Many of these veterans had served and then found themselves released, for medical or other reasons, at an average age of 36.

The New Veterans Charter provides a tax-free payment—up to $306,698 in 2015—in compensation for pain and suffering. Other payment programs were designed to compensate for loss of income and to support ill or injured veterans while they are in rehabilitation programs.

The result was a seven-pronged program:

- Disability award

- Death and detention awards and other allowances

- Rehabilitation services and vocational assistance

- Financial support

- Career transition support

- Group health benefit, family support

- Case management

It was stickhandled through Parliament by Veterans Affairs Minister Albina Guarnieri in 2005, one of the few pieces of legislation passed in the brief tenure of Paul Martin’s government. In asking for quick passage of the bill, Guarnieri said, “What we are presenting here is what was negotiated and what was acceptable at this point in time. My attitude is that this is a living charter. It is malleable and open to improvements down the road.”

“I have to admit if it was not for the assistance I receive from VAC, I would not be able to stay in my home.”

The charter’s coming into effect on April 1, 2006, was hailed with much fanfare by the new government of Stephen Harper at a ceremony in the Reading Room on Parliament Hill. Speaking to veterans in the room, Harper said, “Because brave men and women like yourselves have stood up for Canada both at home and abroad, our government is committed to standing by you today by moving forward on the New Veterans Charter. The charter will offer comprehensive levels of support to those men and women who are injured or disabled while serving Canada. In the future, when our servicemen and women leave our military family, they can rest assured the government will help them and their families transition to civilian life.”

The fact that this would be a living document was reiterated by Veterans Affairs Minister Greg Thompson. “This is just the start,” he said. “It is a living document. It is an open charter. We are totally committed to improving this as required. It is a foundation that can be built upon as needed. The book is never closed.”

If the charter is a living document, then it is often in need of resuscitation. Five years passed before any change at all was done to the document.

As Veterans Ombudsman Guy Parent said in his 2013 report, Improving The New Veterans Charter: The Parliamentary Review, “At the time the New Veterans Charter came into force in 2006, it represented a fundamental shift in the approach to the care, support and compensation of injured and ill veterans compared to the Pension Act. It changed the legislative approach from one that inadvertently encouraged veterans to focus on disability (the greater the disability, the greater the financial benefit) and did little to address the transition needs.”

Veterans groups appeared before parliamentary committees, wrote letters and supported the Veterans Ombudsman’s Office in calling for changes, such as allowing the lump payment to be taken at once, received in annual payments or a combination of both. Other measures called on programs to provide compensation of at least $40,000 a year. In all, more than 200 recommendations for improvements to the NVC were proposed in various consultations.

Yet there has been only one updating of the living document since it was introduced. That was in 2011 and many recommendations were not acted upon at that time and many more have arisen since then.

After that, the living document remained static despite numerous calls from the ombudsman and parliamentary committees for more changes to keep up with the needs of the current veteran, especially in light of a spate of suicides in 2013–14 (The Veterans Revolt, November/December). The House of Commons Standing Committee chaired by MP Greg Kerr released a report in June making 14 specific recommendations, but when the required time for the government to respond arrived, it was met with vague promises and no timetable (Government Response To Charter Changes Disappoints Veterans, November/December).

The Royal Canadian Legion spearheaded a letter-writing campaign to Veterans Affairs Minister Julian Fantino and members of Parliament calling for three major changes to the New Veterans Charter. Within the first month, there were more than 10,000 letters (Letter-Writing Campaign Launched By The Legion, January/February). Just before being castigated in a report from the Auditor General on mental health for veterans and serving members, the government announced an extra $200 million for the mental health of veterans, but that money was to be spread out over a number of years.

The New Veterans Charter does need improving, but in the clamour it should not be lost that the charter was something fought for and supported by veterans and the Legion.

As the Standing Committee on Veterans Affairs said in its report, “The committee members unanimously agree that the principles of the NVC should be upheld and that these principles foster an approach that is well suited to today’s veterans.… The legitimate criticisms of various aspects of the NVC should not overshadow the fact that it is a solid foundation on which to help veterans transition to civilian life when a service-related medical condition prevents them from continuing their military career.”

The government needs to act, but the foundation is there for a benefits program to rival the quality of that which followed after the Second World War. As we enter the centenary period for the First World War, it is important to remember that looking after veterans is a job that has continued to this day and will continue as long as there are volunteers willing to wear the country’s uniforms.

How RCMP members fare

by Sharon Adams

After Sergeant. J. Claude Scott retired from the Royal Canadian Mounted Police in 1988, he dismissed his back pain as arthritis. He didn’t connect the pain with his 22 years of service, even though he spent a year and a half in and out of hospital recovering from a motor-vehicle accident in 1973, when he swerved his police car to avoid a head-on collision.

Eventually Scott, who now lives in Rockland, Ont., returned to duty. “Sometimes I had difficulty, but I could walk, I could run.” After leaving the RCMP he went on to a career in the civil service, but the pain steadily worsened. “I didn’t know what was going on in my body.

“In 2000, a good friend of mine, also a retired sergeant, asked me ‘Why don’t you apply for a disability pension with Veterans Affairs Canada?’” said Scott. “I said ‘What are you talking about? I’m not from the Canadian Armed Forces.’”

What Scott didn’t know is that Veterans Affairs Canada adjudicates and administers disability pension claims on behalf of the RCMP. He is not alone. “Many of our members and veterans don’t know about VAC services and benefits available to them,” said Ron Lewis, national advocate for the RCMP Veterans Association.

Scott applied for and was awarded a disability pension for damage to his arm and spine. He is now one of VAC’s 10,600 RCMP clients.

In order to increase knowledge about these benefits, VAC began conducting RCMP transition interviews in April 2014. But some older veterans, particularly those who retired decades ago, may not realize they are eligible to apply. Others may not connect to their service the slow development of health problems such as hearing loss, joint problems or post-traumatic stress disorder and other mental-health issues.

RCMP members, veterans and certain civilian employees with permanent service-related illnesses and injuries are eligible for disability pensions and benefits authorized under the RCMP Superannuation Act and the RCMP Pension Continuation Act and awarded and administered under the Pension Act. The Pension Act also covers some Canadian Armed Forces veterans, largely from the Second World War and Korean War. While Canadian Armed Forces members released after 2006 fall under the New Veterans Charter, the RCMP did not opt in to that legislation.

“The process for RCMP members, former members and survivors who are applying for benefits is similar to that of CAF members and veterans,” said VAC spokesperson Janice Summerby. “VAC can assist with the preparation of applications, and redress mechanisms [for appealing decisions] are in place through the department and Veterans Review and Appeal Board.”

Application forms are available from VAC district offices, Royal Canadian Legion provincial or Dominion Command service officers, Service Canada locations across the country, Veterans Affairs district offices, online at www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/services/after-injury/disability-benefits/how-to-apply, or by opening a My VAC Account at www.veterans.gc.ca/myvacaccount.

Scott opted to deal with VAC on his own, as do most veterans. “I’m a perseverant son-of-a-gun,” he said. “That’s why they made me an investigator.” But not everyone has the patience or eye for detail, and there is lots of free help available, said Lewis.

“I recommend Royal Canadian Legion provincial or Dominion Command (not local branch) service officers,” said Lewis. The service is free and you do not have to be a Legion member to receive help. “Command service officers are full-time professionals, security cleared, and have expedient access to RCMP health records.” In fact, he said, “Legion service officers can get our health records quicker than we can, because members need to file personal information requests under the Privacy Act in order to obtain their health records, a process that could take weeks or many months.”

“The problem is not one with a political party, it is the unaccountable bureaucracy.”

In addition, Lewis said, “service officers know the system and know what VAC is looking for.” The success rate on first application is higher if documents are in order, “and a service officer can make sure of that.” Forms must be filled in completely and correctly and the right support documents need to be included. An applicant statement is required for each condition. Only one application is required.

Having a personal file of health records has become increasingly important, said Lewis. In 2014, RCMP members began receiving basic health-care services through their province of residence. When the RCMP administered and paid for its own health-care system, doctors’ appointments and treatments were billed directly to the RCMP, with accompanying paperwork. “As a result, the RCMP had your health record and all we had to do was go look at the file.”

Now that basic health-care information stays with the family doctor. Doctors keep records, but they move, retire and die and the member may not be able to retrieve records easily or cheaply. Members can be posted in several provinces during their careers, and may not remember the name of the doctor. As well, veterans may not realize health problems they develop later in life are related to earlier injuries, illnesses and conditions experienced while serving.

“As a result, your files are going to be scattered, lost, forgotten. You need to be diligent every time you go to the doctor, and keep your own file,” said Lewis.

Such records are important because they help prove an applicant has a permanent, medically diagnosed disability and that it is linked to service. Incident reports, witness statements and notebook entries from the time of the incident may also be helpful.

Scott had maintained such a file over the years, which helped him with his first application and subsequent appeals, which have increased the total amount of his disability pension.

Once the application is filed with Veterans Affairs Canada, an adjudicator is assigned to determine if the applicant is entitled to benefits, and if so, how much. This is a complex and often user-unfriendly process. A percentage is assigned reflecting the degree to which each condition is attributable to service, the severity of the disability and how much it affects quality of life. Rank and years of service have no impact on the amount of the disability pension.

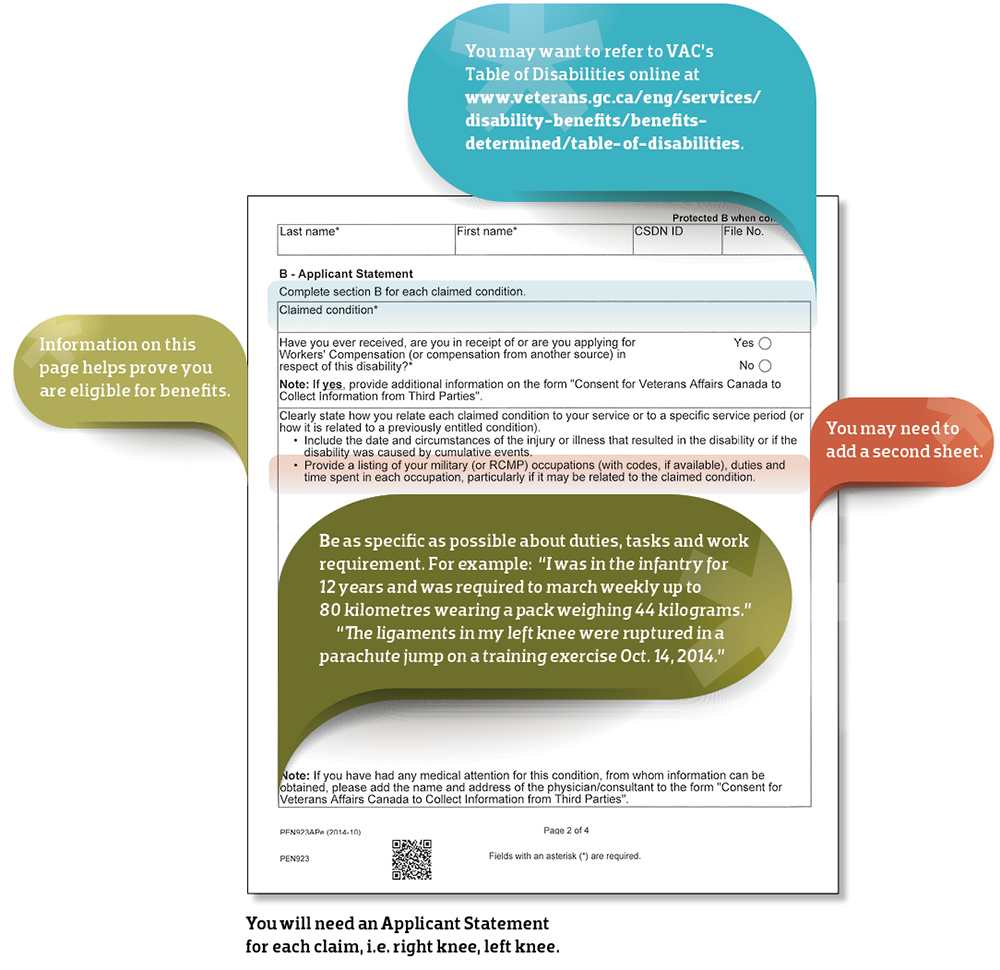

To help come up with those numbers, adjudicators consult VAC Entitlement Eligibility Guidelines, (www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/services/after-injury/disability-benefits/benefits-determined/entitlement-eligibility-guidelines/az-intro), the Table of Disabilities (www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/services/after-injury/disability-benefits/benefits-determined/table-of-disabilities) and Quality of Life Determination Table (www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/services/after-injury/disability-benefits/benefits-determined/table-of-disabilities/ch-02-2006#t01).

The more complete and detailed the descriptions on the application form, the easier it is for an adjudicator to make assessments. Applicants are advised to be as specific as possible about duties, tasks and work requirements. For instance: “In order to meet requirements for firearms certification, I went to the shooting range for an hour every month for 15 years. No ear protection was provided.”

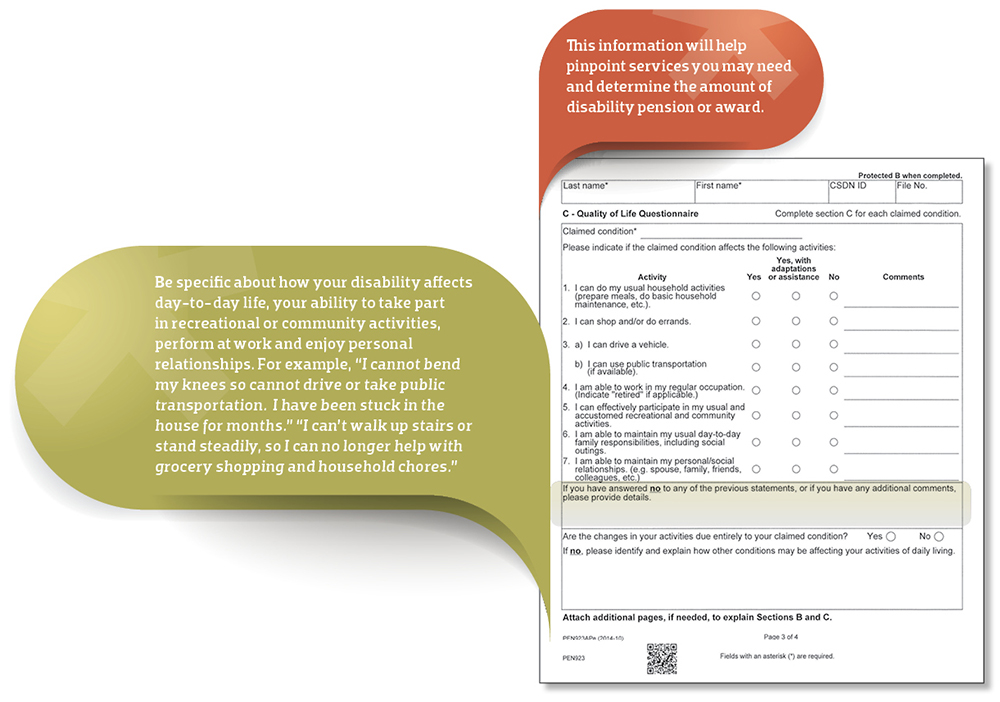

There is also room to describe how the disability impacts applicants’ lives—how they care for themselves, socialize, keep fit, work, take part in community life or enjoy personal relationships. For example: “I can’t drive anymore because I can’t hear sirens. There is a constant, loud buzzing in my ears that makes it impossible for me to concentrate on anything for very long, and causes me to be short-tempered with my wife and children.” Or “I don’t like to go to community events because of constant pain in my knees and hips that make it impossible for me to walk far, stand for long, or sit on pews or folding chairs.”

Once entitlement is proven, it means the veteran or member is covered for life by benefits for that condition, which could include a pension, treatment, therapy, medications and assistive equipment, even if there is no or only a small financial benefit at first. Conditions can be reassessed every two years, and may lead to increases in financial benefits over time.

“A lot of members and veterans don’t realize that once you’re on the books as a VAC client…you may be eligible for an attendance allowance if you later become disabled—and the disability does not have to be related to the pensionable condition,” said Lewis. “You may receive a pension for hearing loss and get an attendance allowance later in life after developing [a health condition such as] MS (multiple sclerosis) or Parkinson’s.”

“No receipts are required to be submitted to VAC, so the veteran may choose services at their discretion,” said Lewis. The Attendance Allowance “is not for home maintenance, housekeeping or mowing the lawn or shovelling snow—if you mention these words, VAC will advise you that you don’t qualify,” he said. Those services are provided to military veterans under the Veterans Independence Program.

Despite years of lobbying and promises that approval is just around the corner, RCMP veterans still do not have access to the VIP, which provides financial assistance to Canadian Armed Forces disability pensioners for such things as grounds-maintenance, housekeeping and personal services. The program was designed to allow veterans to stay in their homes as long as possible as they age, which is good for the veterans’ health as well as that of provincial long-term care plans.

The force continues “to analyse current disability benefits and services to determine how best to meet the needs of RCMP disability,” said spokesman Corporal David Falls.

RCMP veteran Gerry Pumphrey maintains that disabled RCMP veterans deserve VIP services as much as military veterans. “Our battlefield is every day,” he said. “The enemy could be anyone at any time. You never know when it’s going to boil over, or why.”

After retiring from his 30-year career, Pumphrey became an advocate for the Nova Scotia RCMP Veterans’ Association and spent years lobbying for the VIP. Ironically, he could use those services now himself. At 70, he can no longer cope with the groundskeeping on his acreage in Middle Sackville, about 40 minutes from Halifax, where he and his wife have lived for 19 years. He gets nerve blocks every six months so he can deal with the constant pain from injuries suffered in a fall from a horse at the beginning of his career. He receives benefits for hearing loss and back injuries.

“Generally the people that I speak with are happy with the service and a lot of them don’t see any difference with the cutbacks,” said Pumphrey. “They’re happy to get service and the amount of time it takes to get their service.”

Retired sergeant Glynn Norman reports his application process went smoothly—even though he applied for benefits 20 years after retiring in 1986.

He had been warned prior to retirement that he might suffer hearing loss due to years of firing practice at an indoor range without hearing protection. It was not bad when he retired, but worsened over the years. “I thought maybe too much time had passed” to apply for benefits, but he did so after encouragement from some buddies. Not only was his application approved, but a couple of years ago a reassessment showed his hearing loss had worsened, and his benefits were increased.

“If you have any health issues at all that appear to or could have resulted from your service, check into it,” he advises.

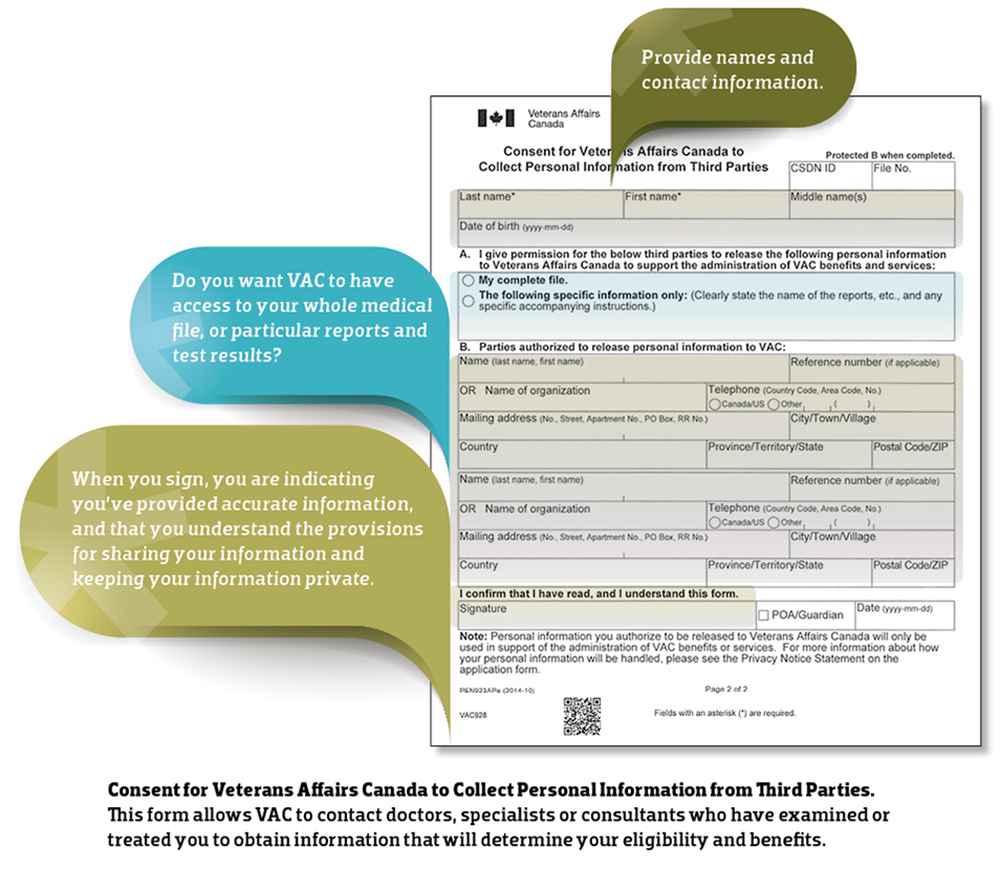

Filling in the forms

by Sharon Adams

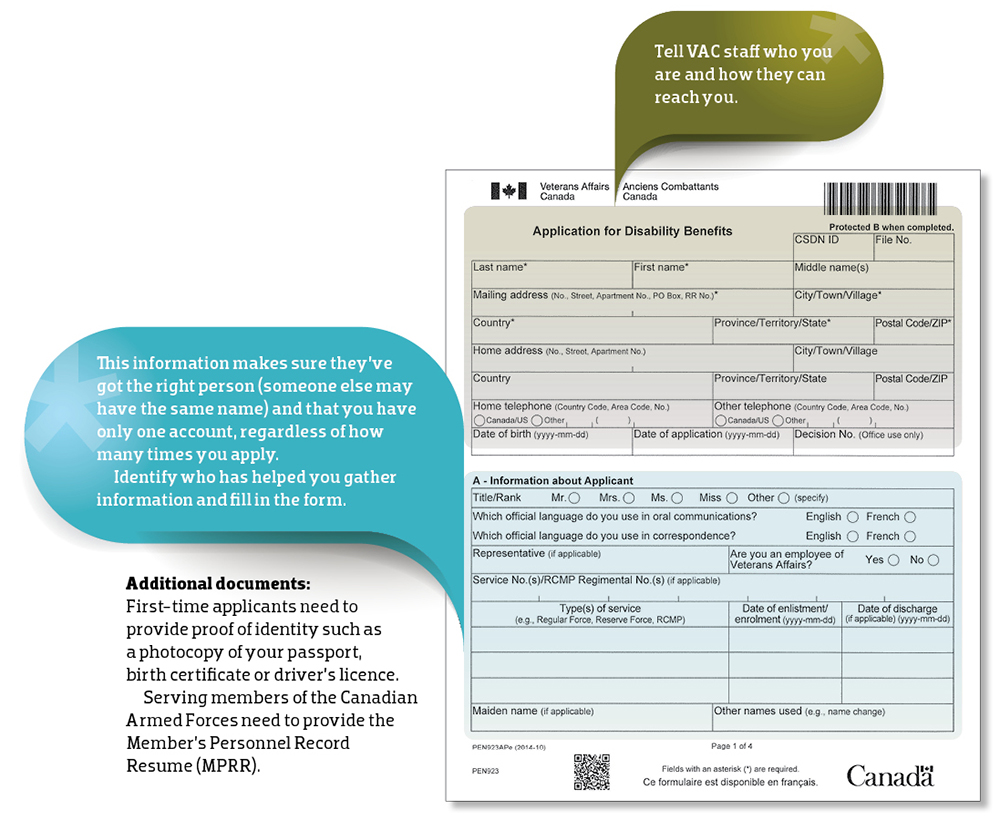

More than 70 per cent of applications are approved on the first try. Most unsuccessful applications either have not included a medical diagnosis or have failed to link the disability to military or RCMP service. To ensure success, make sure the form is completely filled in. Include details that will help the adjudicator determine that your disability is connected to your service, and how that disability affects your day-to-day life.

WHO CAN APPLY?

Serving members and veterans of the Canadian Armed Forces and RCMP and their dependants; those with wartime service in the merchant navy, Allied Forces and in some civilian support roles.

AM I ELIGIBLE?

To obtain VAC benefits, you must have a chronic disability or health condition caused or aggravated by your service. Spouses and children of veterans receiving benefits, or who should have been receiving them, are also eligible for some benefits.

HOW DO I APPLY?

Application forms are available by:

VISITING VAC district offices and Service Canada sites

PHONING Veterans Affairs Canada at 1-866-522-2122 or Royal Canadian Legion at 1-877-534-4666

DOWNLOADING forms at www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/services/disability-benefits/how-to-apply

OPENING a My VAC Account and registering online at www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/e_services/register

PART A Information about Applicant

PART B Applicant Statement

PART C Quality of Life Questionnaire

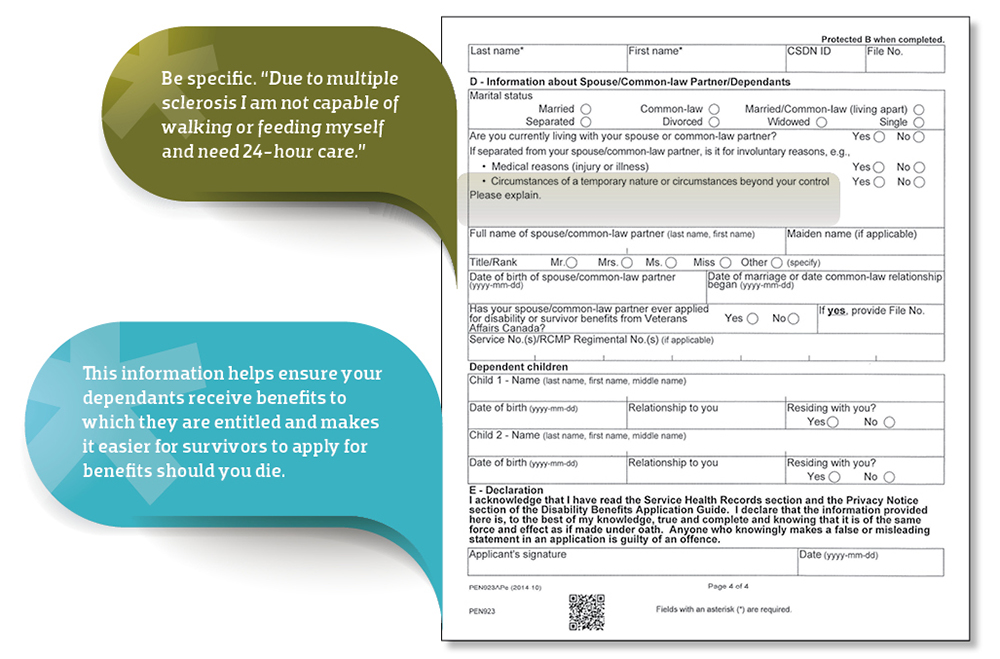

PART D Information about Spouse/Common-law Partner/Dependants

PART E Declaration

HOW THE DECISION IS MADE

The adjudicator will determine if you are eligible by reviewing the application form and additional documents you provided and contacting doctors and specialists for information if you have given permission for them to share your medical records.

Then he or she will determine the amount of the disability pension or disability award by considering how much of the disability is attributable to your service and how badly it affects your life. This will be expressed as an assessment percentage for each claim.

Monthly pensions are awarded for assessments of five per cent or higher for those covered under the Pension Act. A single payment will be given for pensions assessed at four per cent or less. Additional amounts are paid for spouses and dependent children.

Currently, the maximum disability award is $306,698.21. The award can be paid in annual instalments, a lump sum or combination of the two. The disability award calculator can be viewed online at www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/services/after-injury/disability-benefits/disability-award/da-calc.

Unhappy with the decision? You have the right to appeal. Most unsuccessful initial applications are due to lack of medical diagnosis of the disability or failure to link the condition to military service. Fill in the gaps and apply again.

If you’re not successful, you can appeal. The first step is a VAC departmental review, which allows you to bring new evidence or point out errors in fact or law. The department may confirm, amend or rescind the initial decision.

Unhappy with that decision? You can ask for a Veterans Review and Appeal Board (VRAB) review hearing. You will get to tell your story face-to-face with a review panel.

Still unsatisfied? You may request a VRAB appeal hearing, during which a panel will reconsider evidence from the hearing. Although the appeal hearing decisions are usually binding, the panel’s decision may be reviewed if there is new information or there has been an error in fact or law.

In rare cases, the Federal Court will review a VRAB decision due to error in fact or law or overlooked factors that may affect a larger class of clients.

Educational assistance for veterans’ families

If you are a child of a deceased Canadian Armed Forces member or veteran looking to further your studies at a post-secondary institution, you may qualify for the Educational Assistance Program (EAP) funded by Veterans Affairs Canada. The Children of Deceased Veterans Education Assistance Act provides financial assistance for four years of post-secondary education for children whose parent died as a result of their military service or who was receiving disability benefits rated at 48 per cent or more.

To qualify, you must be entered into a full-time educational program before your 25th birthday and remain a full-time student to continue receiving benefits. Assistance is provided until the academic year in which you turn 30 years old.

Applicants should note that EAP “does not provide retroactive funding or the reimbursement of education costs to students who have already started or completed their academic studies.” Rather, funding from EAP is provided on a “go-forward” basis. Students can submit their application prior to starting their academic year (which is recommended) or at any point during their current academic year.

Applicants must also include with their submission their high school graduation certificate, a letter of acceptance from the post-secondary institution, calendar description of proposed program of studies and invoice or receipt from the aforementioned post-secondary institution detailing tuition costs and associated fees.

To apply, contact the staff at the nearest Veterans Affairs Canada office or Integrated Personal Support Centre for assistance. The application form, called Application for Special Benefit (Current Students), can also be downloaded directly in a PDF format from the VAC website at www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/forms/document/183.

Using skills and education to make the transition

by Ellen O’Connor

If you are medically releasing for any reason or are a Canadian Armed Forces veteran released with a service-related disability or illness, you may be eligible for vocational services. A Veterans Affairs Canada case manager will look at the skills and education you used in your military career and see how they can be transferred to a civilian job.

You may then be referred to CanVet Vocational Rehabilitation Services, which provides the vocational components of VAC’s Rehabilitation Program to help modern-day veterans smoothly and effectively adjust to civilian life by achieving their employment goals and returning to the workplace. It works with a network of service providers and experts across Canada and is comprised of WCG International HR Solutions, IRC Innovative Rehabilitation Consultants and March of Dimes Canada.

WCG International HR Solutions is based in Victoria and works with governments, businesses and community partners to help people who receive financial assistance or with disabilities find long-term employment. Since 1995, it has placed more than 56,000 clients in long-term employment positions across Canada. WCG’s vocational-rehabilitation team expanded in 2008 when it began operating CanVet.

IRC Innovative Rehabilitation Consultants is a Saskatchewan-based company that has operated since 1997. IRC believes in a proactive approach to help veterans return to work and offers individualized services, such as medical and vocational case management, job-search assistance and transferable-skills analysis.

March of Dimes Canada has provided programs and resources for people with physical disabilities, beginning with its movement in the 1950s to fund the development of a vaccine to end polio, dime by dime. Its programs range from employment and business services to assistance devices and polio/post-polio services.

The vocational services provided by CanVet are executed in three steps. The first step in determining your vocational goals is assessment—which includes analyzing information regarding potential to return to the workplace, and discussing work history, existing skills, ability to learn new skills, interests, and specialized assessments.

The second step is planning, which includes identifying goals and your next steps in achieving them. The third step is developing a personalized plan to provide you with the tools and training to succeed. This can include educational upgrades through college or certifications, work trials and improving interview and job-search skills.

Throughout the vocational preparation process and even continuing on into the workplace, CanVet provides full support to help veterans develop the skills and abilities to find and secure a job and will work with veterans and employers to ensure a successful working relationship.

In some cases, vocational services for veterans are offered to a veteran’s spouse, common-law partner or survivor.

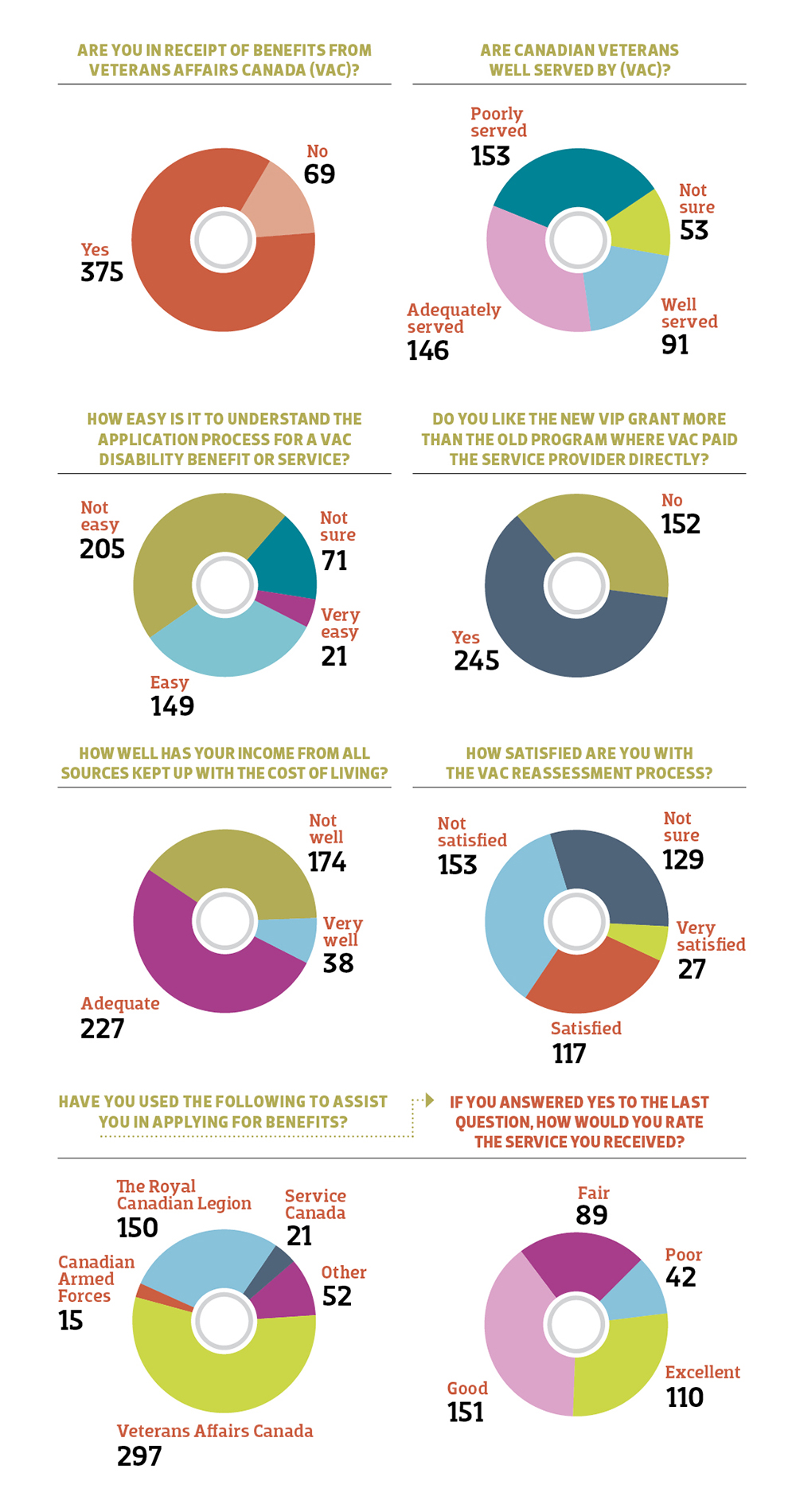

A long way to go

by Adam Day

The results are in and they are conclusive: Canada’s veterans are not happy with the way Veterans Affairs Canada handles their treatment.

Just as we did last year for our annual March/April special issue on veterans in Canada, Legion Magazine again has conducted a nationwide survey of its readers to better understand how veterans perceive VAC and its handling of their cases.

Of the 449 responses we received, 90 per cent were veterans of the Canadian Armed Forces and Royal Canadian Mounted Police, or were currently still serving. Of those respondents, 84 percent are currently receiving benefits from VAC.

Last year when we asked veterans whether they were being well-served by VAC, the response was clear and certain: No. In fact, during our last survey an overwhelming 77 per cent of respondents expressed some degree of unhappiness with the way VAC treats them, with nearly half of the veterans selecting the most negative answer possible to indicate they are being “poorly served.”

This year, however, things have gotten a little bit better. Just as we did last year, we asked a simple question: “Are Canadian veterans well-served by VAC?”

The answers are clear: Things need to improve. A total of 153 respondents—34 per cent—indicated they are being poorly served, the most negative answer possible. An additional 146 veterans indicated they are being adequately served—33 per cent—while only 91 veterans selected ‘well served’ to describe their treatment from VAC. So, that’s it, the numbers are in—only 20 per cent of surveyed veterans feel they are being well-served by VAC, with 67 per cent indicating that VAC needs to do a better job. While this is a slightly better report card for VAC than last year’s survey, it’s still far from a passing grade.

In addition to the overall assessment of VAC’s performance, we also asked our readers some more-specific questions to determine if there are any other possible issues.

For example, Canada’s veterans continue to find VAC’s services too complex, its bureaucracy too confusing. When asked how easy it is to understand the application process for a benefit or service, 205 out of 449 respondents said it was ‘not easy,’ while only five per cent gave the most positive answer, that it was ‘very easy’ to apply for benefits or services.

Another notable sore spot in our survey concerned financial support and whether it was keeping up with the always-rising cost of living. While 30 per cent of respondents were not satisfied with the support they receive from VAC, 38 per cent indicated they are satisfied, and only 19 per cent noted that they are very satisfied. A whopping 174 respondents—39 per cent—indicated that their income from all sources is not keeping up with the cost of living, with only eight per cent saying their income has kept up ‘very well.’

There are definitely some bright spots in veterans care too, however. For example, the recent changes to the Veterans Independence Program, wherein VAC provides a grant rather than paying the service provider directly, generated a positive response, with 245 respondents indicating that they prefer this new system. Indeed, the VIP service is itself quite popular with veterans and is one of the most highly rated programs in our survey, with 63 per cent of respondents saying they are either very or somewhat satisfied, and only 15 per cent saying they are not satisfied.

Another bright spot was the response to VAC’s case-management services, with 47 per cent of respondents noting they were either satisfied or very satisfied with the service, while only 27 per cent were unsatisfied.

We also asked our readers if they had received assistance from various sources to apply for benefits. Many respondents had assistance from more than one source. VAC itself had assisted in 66 per cent of cases while The Royal Canadian Legion rates second, assisting in 33 per cent of cases. The CAF had assisted in only three per cent of cases while 12 per cent had used other services such as Service Canada or other veterans associations.

Many of our respondents also included short notes with their anonymous surveys to provide even more information. While the notes varied from very positive to seriously negative, there were a few that seemed to summarize some of the feelings out there among Canada’s veterans. Many noted that VAC is a large bureaucracy, with its own interests, and that dealing with it can be challenging. “When dealing with VAC,” wrote one reader, “the advice you receive varies with each employee that you speak to!”

On a less critical note, one reader wrote: “I wish to be fair to VAC. Initially [their service] was slow and passive, recently it was really good. What a difference!”

The big picture, however, is not overwhelmingly positive and it’s clear VAC has some work to do if they are to satisfy Canada’s veterans. Right now, the data indicates that only a small minority—20 per cent—feel they are currently being well served by VAC.

2015 Veterans benefits survey results

Following are some of the results from the readers’ survey which appeared in the Legion Magazine’s November/December issue and on our website. We wanted to know what our readers thought of their experiences applying for and receiving veterans benefits. We had 449 responses, but respondents didn’t answer every question and some questions allowed for more than one answer.

We would like to thank those readers who took the time to fill in the survey.

Pensions, awards, allowances for 2015

Veterans Affairs Canada raised pensions, awards and allowances paid under the Pension Act by 1.8 per cent in 2015. VAC adjusts the rates for disability pensions and allowances on Jan. 1 each year. The amount is based on the Consumer Price Index in accordance with the Pension Act.

Readers who think they may be eligible for a benefit related to military service should contact Dominion Command or a provincial command service officer through your local Legion branch.

Back to Top

————————————————————————————————————————————

Frequently Used Terms

(in alphabetical order)

Attendance Allowance

A non-taxable benefit for totally disabled benefit recipients who need an attendant to help with self-care such as dressing, eating and bathing.

Bureau of Pensions Advocates

Lawyers within VAC who provide free legal help for people who want to appeal decisions about disability benefit claims. Website: www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/department/organization/contact. Phone: 1-877-228-2250.

Canadian Armed Forces Income Support

Financial support for those who have completed the rehabilitation program but are unable to find a post-military career or job or have a low-paying job.

Canadian Armed Forces Members and Veterans Re-establishment and Compensation Act

The legislation covering CAF members and veterans applying for benefits for illness or injury related to military service since April 1, 2006, also known as the New Veterans Charter.

Case Management Service

Is available to CAF members, veterans, RCMP members, and their families dealing with a crisis, who have complex needs, or are having trouble making the transition to civilian life. Case managers have access to medical and rehabilitation specialists and other support services.

Clothing Allowance

A non-taxable benefit for either specially-made clothing or for a condition that causes exceptional wear and tear on clothing.

Disability Assessment

Is based on severity of the medical condition and how much it affects quality of life. It is expressed as a percentage.

Disability Award

A tax-free cash award (commonly called the lump-sum payment) for CAF members or veterans with an injury or illness related to military service. It can be paid as a lump sum or in instalments. The award is adjusted for cost of living annually.

Disability Pension

A monthly tax-free payment for disabilities caused or worsened by service in the Second World War or Korean War; merchant navy or some civilian support occupations during wartime; by current RCMP members and veterans; and by Canadian Armed Forces members and veterans who applied for benefits prior to April 1, 2006.

Earnings Loss Benefit

Ensures compensation for loss of income of those in the rehabilitation and vocational assistance programs does not fall below 75 per cent of pre-release military salary.

Education Assistance Program

Provides financial assistance for four years of post-secondary education for children aged under 25 of a CAF member or veteran who died as result of military service or who was receiving disability benefits rated at 48 per cent or more.

Entitlement Eligibility Guidelines

Policy used by VAC adjudicators in determining entitlement to disability benefits. The guidelines help determine if there’s a link between a medical condition or disability and a claimant’s military or RCMP service.

Exceptional Incapacity Allowance

A non-taxable allowance for recipients of disability benefits (including prisoner of war benefits) of 98 per cent or more and is based on shortened life expectancy, pain and loss of enjoyment.

Medical Impairment Rating

A percentage rating based on the severity of medical condition and degree to which it affects daily activities. It is added to the Quality of Life rating to determine disability assessment.

New Veterans Charter

See Canadian Forces Members and Veterans Re-establishment and Compensation Act.

Pension Act

The legislation governing benefits for service-related illness and injury to veterans of the Second World War and Korean War, merchant navy veterans and certain civilians with wartime service, members and veterans of the RCMP, and CAF members and veterans who applied prior to April 1, 2006.

Permanent Impairment allowance (PIA)

A taxable monthly allowance for lost job opportunities due to permanent and severe impairment.

PIA supplement

A taxable monthly benefit for those in receipt of the PIA and who are not capable of suitable gainful employment.

Quality of Life

Is determined by ability to live independently, maintain relationships, take care of oneself and participate in community activities.

Quality of Life level

Is a measure of how much a medical condition has affected quality of life, rated on a scale from one to three.

Rehabilitation and vocational assistance program

Is available to injured and medically released CAF members and veterans who need medical or psycho-social rehabilitation or assistance in training and searching for a post-military job or career.

Royal Canadian Legion Service Bureau

Operated by Dominion Command of The Royal Canadian Legion, the bureau provides advice to those applying for VAC benefits, help in filling out and filing applications for benefits, and support through the application and appeals process, as well as benevolent assistance. The service is free of charge and you do not need to be a Legion member to receive help. E-mail servicebureau@legion.ca. Website: www.legion.ca/we-can-help. Phone: 1-877-534-4666.

SISIP

The Service Income Security Insurance Plan provides replacement income for CAF regular and reserve members medically released due to long-term disability. The plan includes a vocational rehabilitation program.

Survivor’s Pension

For the first year following death, spouses receive the full amount of the pension. After one year, spouses of pensioners rated at 48 per cent or greater disability continue to receive the maximum survivor’s pension while spouses of pensioners rated between five and 47 per cent receive half.

Table of Disabilities

A list of conditions used to assess extent of a disability in order to determine eligibility and amount of benefits.

Veterans Affairs Canada

Manages disability benefits programs. E-mail: information@vac-acc.gc.ca. Website: www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/services/disability-benefits. Phone: 1-866-522-2122.

Veterans Independence Program

Designed to help veterans remain in their own homes as they age, the VIP provides financial assistance for housekeeping, groundskeeping and personal care services to those receiving VAC disability benefits, their spouses and frail veterans. Veterans Review and Appeal Board Provides reviews and appeals of VAC decisions about eligibility and assessment for disability benefits.

War Veterans Allowance

Provides financial assistance for low income Canadian, Commonwealth or Allied veterans who served overseas during the Second World War or Korean War, and their spouses. The amount provided is based on income, marital status and number of dependants. There are similar allowances for merchant navy veterans and civilians who worked in support of the military in wartime.

Advertisement