![After his promotion to Leading Aircraftman in 1940, Henry Cleary was posted to No. 13 Elementary Flying Training School, St. Eugene, Ont. [PHOTO: COURTESY LYNDA MACPHEE]](https://legionmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Halliday1.jpg)

With his Spitfire damaged by flak, Flight Lieutenant Henry Cleary was forced to land in, or parachute into occupied France. Cleary evaded capture, but not for long.

Earlier this year, his niece, Maureen Pospiech of Niagara-on-the-Lake contacted Legion Magazine, looking for a home for her uncle’s wartime logbook. We were honoured to accept it and share a copy with the Canada Air and Space Museum. We also did something else. We asked air force historian Hugh A. Halliday to write a story about the logbook and the airman it belonged to.

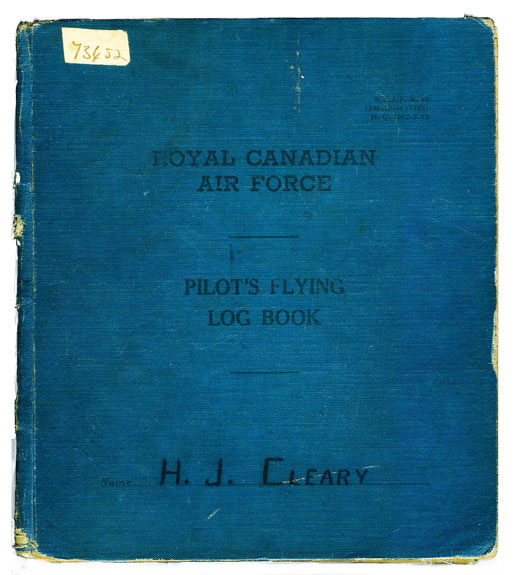

We begin with a logbook. From the dawn of powered flight, every pilot—civil or military—has kept one. So have navigators, flight engineers, air gunners and others “in the trade.” Some record only the bare bones of flying. Others are virtual diaries and scrapbooks. Their owners almost invariably keep them to the very end. Next-of-kin may recognize them as important documents in the story of a loved one, yet time and generational passage may blur their significance. Nevertheless, they help preserve the memory of an adventurous life.

![The airman’s log book. [PHOTOS: COURTESY LYNDA MACPHEE]](https://legionmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Halliday4.jpg)

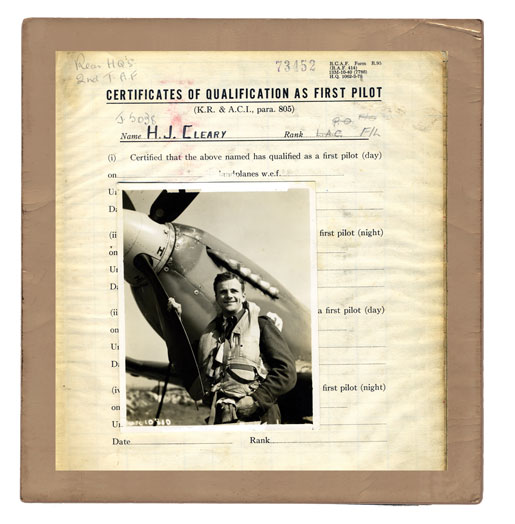

Henry Joseph Cleary was born in Cornwall, Ont., on June 3, 1919. He went to school there, was active in sports and worked in the circulation department of the local newspaper. He was an only son but had four sisters. An album shows him as an altar boy, and vague family recollections suggest he may have considered the Catholic priesthood. In the RCAF he wrote letters home, but they have not been found, and so he survives in his service file, his logbook and a few photographs kept by nieces who never knew him.

Cleary was interviewed by a Royal Canadian Air Force recruiting officer who looked him over and wrote, “Good type—frank—clear eye—steady nerves—intelligent. Well educated, poised. Should absorb instruction quickly. Well built and healthy.”

Sworn in on July 6, 1940, Cleary was posted to No. 1 Manning Depot, Toronto, where he received his uniform and had his first taste of air force discipline. Next stop was Station Trenton for undefined duty and then, on Oct. 23, to No. 1 Initial Training School (ITS), Toronto.

Most of the course was in classrooms, but he was tested in a Link Trainer (an early flight simulator) and deemed fit to be a pilot. Although he placed 53rd in a class of 65, he was regarded highly—“Very good type, keen, cool and reliable,” read the final assessment.

Graduation from ITS brought promotion to Leading Aircraftman and a posting to No. 13 Elementary Flying Training School, St. Eugene, in eastern Ontario. His logbook commenced there on Dec. 11, 1940—40 minutes in a Fleet Finch biplane with a man called “Emerson” as his instructor. The document was terse, recording little more than flying times, the name of the instructor, and what “sequences” (lessons) he was doing.

On Jan. 8, 1941, he went solo for the first time. At St. Eugene he logged 27 hours, 40 minutes on dual instruction and 26 hours, 30 minutes solo. He also “flew” five more hours in the Link, learning the rudiments of instrument or “blind” flying. He graduated 22nd in a class of 34. The Chief Instructor wrote of him, “Conduct good. Ability above average. Very keen and reliable. Quiet disposition.”

Cleary was posted to No. 2 Service Flying Training School at Uplands—south of downtown Ottawa—to master more advanced aircraft—the North America Yale and Harvard. His ground school marks were well above average; he graduated 26th in a class of 63 and was commissioned as a pilot officer on April 11, 1941. He was also able to remove the white flash in his cap which had identified him as a trainee.

Henry Cleary was immediately posted overseas. On June 20, 1941, he commenced a course at No. 55 Operational Training Unit (OTU), Usworth, Durham, England, starting in a two-seat Miles Master aircraft to familiarize him with British flying conditions. Next came single-seat Hawker Hurricanes, learning how to be a fighter pilot. The logbook was dry: “Aerobatics, 25,000 feet” (July 22); “Formation attacks, 20,000 feet” (July 23); “Dogfighting” (July 28), were typical entries.

He now went to an RCAF unit, No. 402 Sqdn. at Ayr in southern Scotland. He was still on Hurricanes, and most of his flying was little more than a continuation of his OTU training. On Aug. 19 the squadron moved to Southend, near London. It was still training—but for a fighter-bomber role. When not engaged in that, the Hurricanes flew convoy patrols. Between Aug. 6 and Oct. 27, Cleary flew a mere 44 hours and 35 minutes—and did not fire a shot.

![Group Captain F.S. McGill congratulates Cleary after he received his wings. [PHOTO: COURTESY LYNDA MACPHEE]](https://legionmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Halliday5.jpg)

He did, however, manage to “put up a black” (commit an egregious error). The logbook entry for Oct. 4 stated almost nothing about it other than he had been piloting a Miles Master, used by No. 402 as an aerial taxi, that he had been airborne for three hours 30 minutes, and that he had “forced landed.” The accident investigation report, found in his service file, was more detailed and embarrassing. He and another pilot had set out on a cross-country flight and became lost in marginal weather. Having exhausted their fuel, they came down in a plowed field. Although neither man was injured, the Miles Master was not a pretty sight. “This pilot did not show good judgment,” was the conclusion.

Whether it was the accident or something else, Cleary was posted to No. 1488 Flight, Shoreham, commencing flying on Nov. 10, 1941. He was now on Westland Lysanders—about as exciting as driving a milk truck. Most often he was towing targets for other people to shoot at and it is not always clear from the record who the “other people” were—other pilots or anti-aircraft gunners. Seniority assured his promotion to flying officer on April 11, 1942, but momentarily he was in an operational rut.

On May 15, 1942, he was attached to Sutton Bridge, Lincolnshire, for a month-long “Pilot Gunnery Instructor” course. He flew Spitfires on exercises, sometimes firing live ammunition, sometime merely “shooting” with a cine camera, but little changed once he returned to No. 1488 Flight—more of piloting Lysander target tugs. His time there ended in October 1943—the past two years must have seemed like purgatory. Yet if he was frustrated, he had remained cheerful and earned generous assessments. “A quiet, conscientious and loyal officer,” wrote Squadron Leader R. Barber on Oct. 26, 1943, giving him a good send-off. Cleary had also been promoted to flight lieutenant the previous April.

He was now posted to No. 59 OTU, Milfield, Northumberland, flying Hurricanes. The course was more intense than what he had experienced at No. 55 OTU in 1941. The terse logbook entries suggest exciting times: “Dogfighting”; “Battle Formation”; “Low Level Cross-Country, 200 feet”; “Air Firing on Drogue” (on two such exercises he actually shot the target drogue clean away). He did not mention, but his service documents did note that on Jan. 7, 1944, he had been waiting for a night takeoff when another Hurricane taxied into his tail.

![Henry Cleary [PHOTO: COURTESY LYNDA MACPHEE]](https://legionmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Halliday7.jpg)

Having flown 72 hours, 30 minutes on the OTU course, he was sent to No. 1 Tactical Evaluation Unit, Tealing, Scotland, for advanced air fighting practice, first on Hurricanes and finally on Spitfires. Early in April he caught up with the war when he was posted to No. 602 Sqdn. at Detling, Kent. Suddenly the logbook came alive.

On April 11, following a one-hour-50-minute sortie, described as “Withdrawal support to six Mosquitoes,” he wrote, “My first show!!! Rendezvous on deck at The Hague. Bit of flak, bags of twitch [nerves].” There were more sorties and training flights—all uneventful—and then, on April 25, an attack on a NOBALL [V-1 launching site] when he was airborne 70 minutes—“My first bombing show!!!. No flak but bags of twitch anyway.”

There was more of the same in May, sometimes two NOBALL strikes in a day, but there were no more exclamation marks until June 6, 1944, when he flew two sorties. For the first, which lasted 35 minutes, he wrote, “D DAY!! at last. No Huns, lots of craft in Channel—WIZARD SIGHT—Returned early, oil on the windscreen.”

In Royal Air Force slang, “wizard” was an adjective for “really good,” “attractive” or “ingenious.” Crews reporting a “wizard show” had been on a very successful mission. In Cleary’s case, it refers to the spectacle of ships in the English Channel, and what they represented.

The second trip—one hour and 55 minutes—was disappointing. “No enemy reaction! Saw [HMS] Warspite shelling inland.”

Many subsequent entries read, “Low cover to assault forces.” June 20 was another day for exclamation marks as No. 602 moved to Airfield B.2 at Bazanville, France. By the 25th they had moved to B.11 at Longue-sur-Mer. The entry for the 26th (a 100-minute beachhead patrol) was ominous—“Fired on by flak from Caen—mighty close.”

On the 28th he flew his first “Armed reconnaissance”—best described as “looking for trouble,” flown at roughly 5,000 feet which allowed pilots to detect German road traffic but also put them in range of medium-calibre anti-aircraft fire.

It was on such a mission on July 1 that he went missing. His squadron was flying some 30 miles southeast of Caen when he reported being hit by flak. He asked for a heading that would bring him to friendly territory, then disappeared into cloud. A staff officer duly made the last logbook entry—“Did not return—hit by flak—forced landed.”

![The grave of the young airman. The Commonwealth War Graves Commission later installed a permanent headstone. This temporary marker gives a date of death of July 1, 1944. The date of death was later updated to July 8, 1944. [PHOTO: COURTESY LYNDA MACPHEE]](https://legionmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Halliday6.jpg)

He had been flying Spitfire MH512 (code letters LO-Q). Squadron Leader R.A. Sutherland wrote his family that day, expressing the usual sentiments of regret, tinged with hope that their son might still be alive. A telegram reporting him missing was dispatched on the 4th. For the moment he was lost in the fog of war. It would be another two months before the fog cleared.

Although the final logbook entry stated that he forced landed, other reports were to the effect that he had parachuted successfully to earth. From there forwards, there is little certainty. He spoke French, had been trained how to evade capture, and probably put that into practice. At some point he linked up with several other men. One was a Frenchman—Jean Foncu—and another was Lieutenant Maurice Larcher, a British officer who had been parachuted into France the previous February with a radio. They were betrayed by a French quisling, and on July 8 were besieged in a farmhouse. Foncu escaped. Another man (possibly a downed airman) was captured. Larcher (with his radio) and Cleary were killed.

Did they die in the firefight? Were they shot against a wall? We do not know. The only certainty is that Larcher was posthumously Mentioned in Dispatches.

The Commonwealth War Graves cemetery at Bretteville-sur-Laize, south of Caen, holds 2,958 burials. Most of them are Canadians killed in the Battle of Normandy. One of them is Henry Joseph Cleary whose logbook remained in storage for three years until it was mailed to his family on April 26, 1947.

Advertisement