“They cannot knock on your house door, take you by the hand and bring you to the clinic. If you don’t ask for help, nobody will come.”

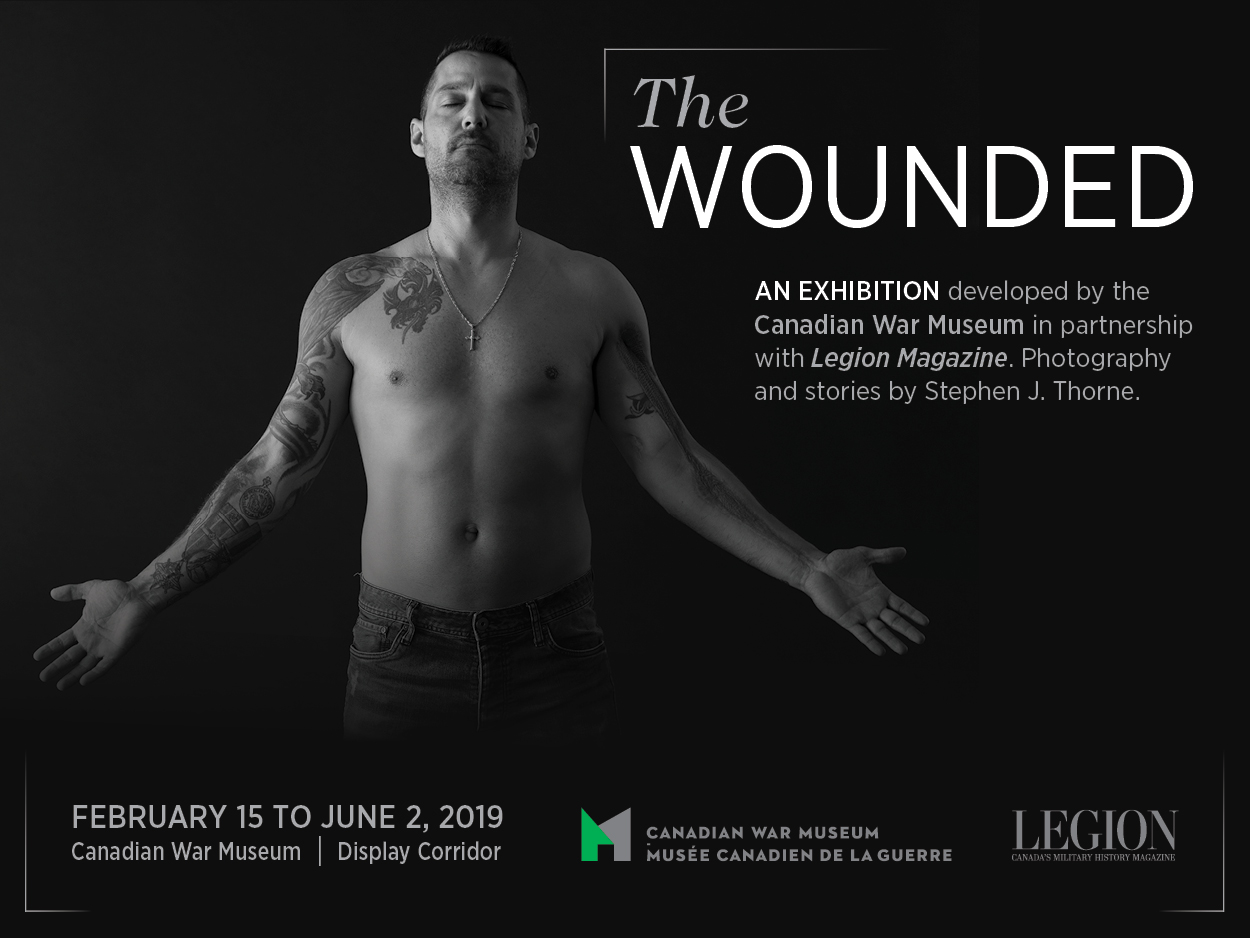

Story and photography by Stephen J. Thorne

As a member of 5 Field Ambulance in Afghanistan, medic Macha Khoudja-Poirier treated so many patients with such a variety of ills and injures, she didn’t know what more she could see to fill out her “trauma book.”

Better known in English as a casualty book, the journal is a log of the cases a medic handles, like the “life list” birders keep of the birds they see or the logbook a pilot maintains of the planes they fly and the hours spent airborne.

Khoudja-Poirier’s book covered the gamut.

There were skin infections, dust-filled eyes and twisted ankles; camel spider bites, head injuries, broken bones and every degree of burns. She saw so many gunshot wounds that they became “as interesting” as the annual parade of la grippe cases during flu season. Then there were the amputations and the deaths.

Deployed to replace a medic killed in action, the first gunshot wound she saw was daunting. By the time she left Afghanistan that first tour, the native of Caplan—a tiny village on Quebec’s Gaspe Peninsula—was demanding the most challenging cases.

“By the end I was telling them, ‘give me the worst one,’” she said. “I liked it. I was totally desensitized. I had no emotion at all. Like, nothing.

“Sometimes the other medics were crying about someone who died or something that was not nice to see. I didn’t understand why.”

She had joined the military in January 2001. She was at CFB Borden in Ontario, just finishing her first-level training toward becoming a medic, when 9/11 happened.

“While we were taking the course picture, someone came into the room and screamed: ‘Stop! Stop! Come see the TV!’ We all moved to the canteen to see what was happening. Maybe two hours later, we all had to go prepare our kits, just in case. We were on an eight-hour call-up. One person quit the next day.”

Khoudja-Poirier started recognizing how much she had changed in the spring of 2007 when she returned to life in Canada. It was a huge adjustment, coming down from the constant state of awareness that had become a way of life in the war zone.

“Nothing was fun; nothing was bad. It was hard to have an emotion—a good one or a bad one. You have hyper-vigilance. It was hard because it’s so intense [over there] you feel that you belong in this other place and you just want to go back.

“Nothing [at home] is as fulfilling or intense. You’re working in the clinic and you’re looking for the same kind of thrill. But, forget it.”

Then there were the nightmares.

She recalls one night in Afghanistan sleeping outside beside her armoured vehicle, as one does, and waking up to the sounds of explosions nearby. Usually, she would put her eyeglasses inside her boots next to her head but, this time, amid the chaos surrounding her, her boots were not in their usual place. And she couldn’t see where.

“Everybody was still with their weapon in the truck and, me, I was still looking for my glasses. It was one of the first moments that I was scared. You just hear boom, boom, boom, tatatatatat around you and you can’t see anything.

“I had a lot of nightmares about that.”

She had developed serious neck problems from her pack and night-vision-equipped helmet. She was training to serve as a gunner on the Bison ambulance when she finally was forced to see a doctor and physiotherapist.

X-rays and an MRI revealed she had a herniated disc and arthritis throughout her cervical region. It was so bad she could hardly walk.

The doctor told her she had no future in the military. Khoudja-Poirier rejected the diagnosis, and landed a master-corporal’s position in charge of the clinic in Kandahar.

“It was a huge [departure] for me. I wanted to be on the ground, not on the base.”

It was 2009, and it didn’t take her long to get outside the wire. Within weeks, she was filling in for a medic at a forward operating base.

Between missions, she had told herself she needed to start feeling things more, having emotions. And she did—more than she’d counted on. She became overly invested in her patients and, when asked to stay on at the FOB after five weeks, she declined. “I had reached my limit. It was too hard, emotionally, to see more.”

Her new role demanded that she be aware of everything that was happening, everywhere. She read volumes of after-action reports and medical records.

“You know everything,” she said. “You have the big picture and the big picture is not beautiful. You come to realize, ‘it’s a shitty place here.’”

On July 6, 2009, a CH-146 Griffon helicopter crashed, killing three soldiers, a Brit and two Canadians, Master Corporal Patrice Audet, 38, and Corporal Martin Joannette, 25.

The pilot’s visibility had been impaired by a dust ball created by its own blades. They flew into a defensive berm at the edge of the base.

Dust ball training was mandatory, but a subsequent report on the crash said most crews, including this one, only received the “theory portion of the dust ball training.” They had watched the maneuver but never attempted it.

Furthermore, the Griffon’s weight limits had been modified. Its original weight restriction in Afghanistan had been 10,300-10,700 pounds. Senior staff feared that would limit operations, investigators reported, so they changed the flight manual to 11,750-11,900 pounds.

The change had disastrous implications for the chopper in question. Its low altitude brought what is known as ground effect into play, reducing its lift.

One of the chopper pilots, a woman, was crying in the clinic as she explained what had just happened. The scene was a turning point for Khoudja-Poirier. After the post-incident debrief, she was sad and frustrated by the futility of it all.

“A part of you is confident that you are there for a good reason and you really help people. But it’s too big to make a big change. You can change small things but that’s it. So you’re just losing your faith, day after day.”

The lack of control over stupid decisions was an endless source of frustration. She was part of a daily patrol that headed out to a forward operating base and back.

“Every day, day after day for two weeks, we were going along the same route at the same time, the same everything.”

Their interpreter had picked up chatter on the radio: Taliban were talking about hitting their patrol. “He heard some bad things and he was very scared.”

The officer commanding had sought a change in their timing, at least, and had been told no. One morning, they awoke to find that the interpreter had quit.

“So the morning we lost the ’terp, we had to find someone to take his place. We were supposed to be leaving at eight o’clock in the morning but when we were supposed to go, our radio broke. So another convoy left in our place.

“This convoy exploded instead of us. They were lucky. There were injured people but no dead. A lot of things there were obvious like that. But you receive orders and you don’t have a choice.”

After seven months overseas, she was so exhausted, she had slept through a rocket attack. She returned home from her second tour in October 2009.

“After that, you’re disconnected from normal life,” she said. “I wanted to go back.”

She went back, all right. But not to Afghanistan.

In January 2010, there was a magnitude 7.0 earthquake in Haiti, killing an estimated 160,000 people. Just three months after returning from a traumatic tour at war, Khoudja-Poirier volunteered to go to a natural disaster.

“I was not happy in Quebec,” she said, describing how she felt like a fish out of water back in Canada. “You were just waiting to have your life back. You were just waiting to be normal as you were before the first time.”

She had changed dramatically, however, and she was only just beginning to process it. Friends would invite her to go out to a movie or participate in activities, but she was not interested.

“Sometimes you just say no. Sometimes you are trying because you need to make an effort if you want to live like the others. In addition, you have to pay bills but you do not care about that; it is not important.

“When I first came back, I slept on the floor for two weeks because my bed was too soft.”

She took one of the first flights into Haiti and the last flight out, four-and-a-half months later. She had just had her 27th birthday. “I didn’t want to go back home. I didn’t have any kids, no husband, nothing.”

She had seen many amputations in Haiti but they were not the result of violence. That made a difference. The work was rewarding and the people were grateful, despite their dire circumstances.

Life back in Canada, on the other hand, was worse than ever. “I was totally disconnected, emotionally and physically.”

Now a sergeant, she volunteered to return to Afghanistan in 2011. Before she started training, however, she met her future husband, Nicolas Bergerat, a Forces weapons technician who left the military in March 2018.

“I thought it would be a good reason to stay here and start a normal life.”

She was offered the chance to reconsider her decision to deploy and she did.

“I was not doing very well. But I was trying to look as normal as possible.”

The hyper-vigilance, the anxiety, fatigue and nightmares all persisted. She had seen patients with post-traumatic stress disorder and thought, “it’s OK for them but not for me, so I refused to have that problem.”

Her post-mission mental-health questionnaire indicated she was in a depression. She was recalled to undergo an assessment by two psychologists. She fooled them both. “I convinced them that I was OK, and I convinced myself too.”

By 2017, however, her husband told her she needed help. They were at CFB Borden at the time. It had been more than 10 years since her first deployment and her condition had deteriorated by the year.

She went for a consultation and was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder. “I’d waited 10 years.”

Khoudja-Poirier left the military in September 2017.

“By the second mission, they were making a lot of efforts to support us mentally,” she said. “But they cannot knock on your house door, take you by the hand and bring you to the clinic. If you don’t ask for help, nobody will come.

“If you can’t do the job, you’re just a ‘bad soldier.’ Nobody will ask you why. I saw that, and I did that, too. You don’t ask; you judge.”

Now Khoudja-Poirier is a mother of two and a real-estate agent in Gatineau, Que. She is much better, but still battles the cycles of her disorder. “I’m starting to accept that. It’s hard.”

___

An exhibition developed by the Canadian War Museum in partnership with Legion Magazine is on display now. Photography and stories by Stephen J. Thorne.

Advertisement