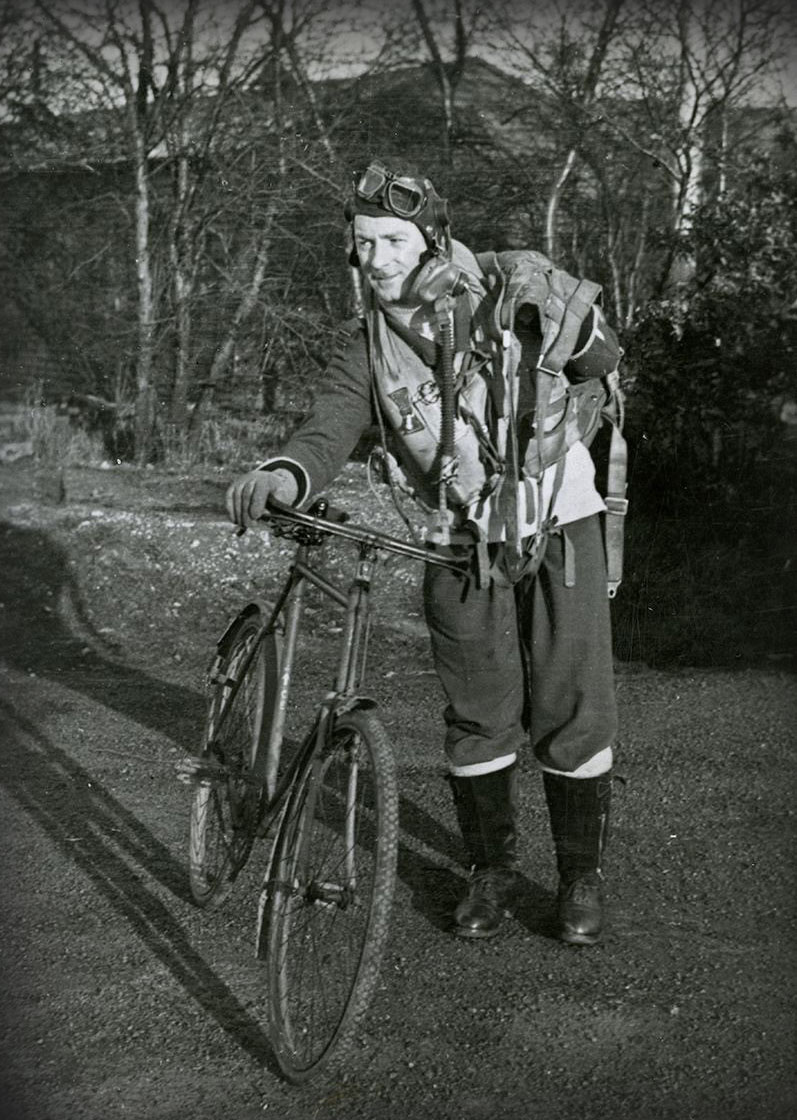

The black-and-white image (ABOVE) shows a classic 1940s-era air force pilot all kitted out for operations, his goggles tilted at a jaunty angle atop his leather-helmeted head, oxygen mask dangling off one side of his face, parachute slung over his shoulder.

A life vest covers his uniform, his pants are tucked into sheepskin boots and his gloved hand rests on the handlebars of the kind of British Small Arms bicycle he would have ridden out to the flight line at the outset of each mission.

The notation scrawled on the back of the photograph in my dad’s unmistakable handwriting identifies the pilot as Flight-Lieutenant W.S. Johnston and places the location and date at Biggin Hill, December 1943. The billets are behind him.

I had always assumed Johnston was a Spitfire pilot. My dad was in No. 401, RCAF, at the time, a vaunted Spitfire squadron, and Biggin Hill in the south of England was a noted fighter base. But in researching a memoir I wrote on my dad last year, I could find no record of a W.S. Johnston associated with 401.

I recently went back to it, this time conducting a more general search. It was not long before I found him, I believe: Flying Officer William Smith Johnston, a Mosquito pilot from Renfrew, Ont., 90 kilometres west of Ottawa.

I eventually visited Library and Archives Canada, where I viewed his service record and filled out the profile of the man I believe my father photographed.

Born Oct. 28, 1917, to Frank Henry and Ida May (Smith) Johnston, he was the youngest of four children in a farming family that included three boys. A hockey and rugby player, he served as quartermaster-sergeant in the Lanark and Renfrew Scottish Regiment before he signed up with the RCAF in 1940.

“We have always found him painstaking and efficient in any duties assigned to him,” regimental Captain W.M. MacAndrew wrote to the air force on Jan. 24, 1940.

His high school principal, A.B.C. Throop, described him as an “excellent student, thoroughly reliable.” The mayor of Renfrew, Dr. C.W. McCormack, a family friend, said he was “a bright, upright boy.” And his minister at North Horton United Church, Walter Campbell, said he had known “Billie” for years, describing him as a “gentleman” and vouching for his “reliability and trustworthiness.”

“William Johnston is one of the most energetic and initiative [sic] young men of our community,” Campbell wrote. “His Christian qualifications, his high ideals and good morals and cheerful disposition, I do not hesitate to point out.”

“Quiet, cool, modest and very conscientious,” according to his air force assessments, Johnston was serving with No. 21 Squadron of the British Royal Air Force when my dad took his picture.

Why he would be in Biggin Hill is a mystery. No. 21 was based at Sculthorpe, 220 kilometres away, although Johnston’s records state that he had been in Grangemouth in Scotland, likely training on the squadron’s new Mosquitos. His next posting was with the main squadron at its new billet in Hunsdon, just 40 kilometres away.

He was the only W.S. Johnston I could find in either the RCAF or RAF, however, and, as it turned out, my father’s picture may have been the last photograph taken of him.

On Jan. 21, 1944, a few weeks later and four years almost to the day after he joined the air force, Johnston, along with his navigator—Pilot Officer Leslie Hocking of the RAF Volunteer Reserve—was killed after colliding with another Mosquito.

They had just attacked a V-1 construction site in the Pas-de-Calais area of France. The other crew also died. The details are unclear—likely they survived the collision and were limping back to England—but both planes were subsequently hit by anti-aircraft fire and crashed into the English Channel, seven kilometres north of Dieppe.

In his official service record, an eyewitness reported that “on leaving the French Coast, after having bombed the target, FO Johnston’s aircraft was seen to be hit.”

“At the time, he was doing violent evasive action at low level, when his aircraft was hit again in the tail which then disintegrated. The aircraft flew on for a short distance before crashing tailless into the sea.”

RAF Squadron Leader Arthur Marsden Lewis Alderton and his American navigator, Lieut. Bertram L. Chaiet of the United States Army Air Force, also died in the incident. Chaiet had emigrated to New York from France. He had originally enlisted in the RCAF, then transferred to the USAAF, presumably after the Americans declared war on the Axis powers following Pearl Harbor.

My dad, Flt. Lt. Edward L. Thorne, would wax on about the fabled Spitfire with reverence, emotion and deep affection. The de Havilland Mosquito with her two-man crews, on the other hand, he remembered with something like awe.

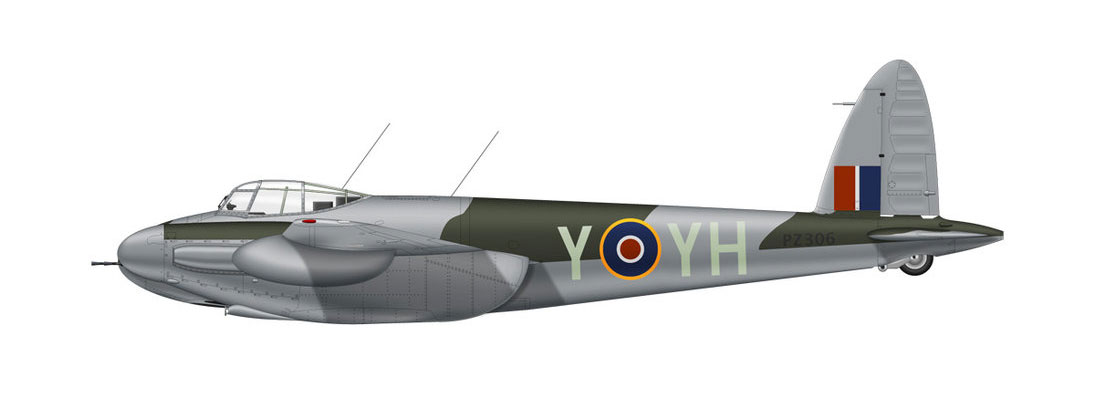

While bigger, more heavily armed bombers like the Lancaster and B-17 lumbered along with their massive payloads, the all-wood, lightly armed “Mossie” could fly lower, higher, faster, farther, albeit with a fraction of the hitting power.

The birch plywood, spruce and Ecuadorean balsa from which the Mosquitos were made were readily available. Their fabrication was contracted out to furniture factories, cabinetmakers, luxury-auto coachbuilders and piano makers. No rivets needed, their surfaces were smooth and battle damage was easily repaired.

Apropos then that Johnston, who was also certified in Wellington bombers, ended up in Mosquitos, as his principal said his high-school education included two-years’ training in woodwork and the pilot listed “carpenter work” as his sole hobby.

The Mossie was adapted to multiple roles, including daytime tactical bomber, high-altitude night bomber, a pathfinder for the heavies, day or night fighter, fighter-bomber, intruder, maritime strike aircraft and fast photo-reconnaissance aircraft.

But it was their secret missions that intrigued my father.

They thrived on pinpoint, low-altitude, hit-and-run raids that did more to boost Allied morale and discourage the enemy than impose significant damage on Nazi infrastructure. No dam-busting or Dresden firestorms for these guys.

And they did it with pizzazz.

In Jutland, the raiders went in so low that a crewman saw a Danish farmer in a field salute as they zoomed past. In Copenhagen, they flew down boulevards and banked into side streets.

Once their exploits became known, the British press—and public—ate them up with glee.

A month after Johnston died, on Feb. 18, 1944, several Mosquitos from his own 21 Squadron participated in Operation Jericho, a low-level attack on the German prison at Amiens. The raiders busted down walls, destroyed guard towers and freed 258 prisoners, a third of them French resistance fighters (182 were recaptured). (See footage of the raid.)

Collateral losses could be high. More than 100 prisoners died in the Amiens attack, and the Nazis performed 260 reprisal executions in the aftermath. At a Catholic school in Copenhagen, 27 nuns and 87 children were killed by wayward bombs.

But, as Stephan Wilkinson wrote for Aviation History Magazine in 2015, the effect on the German psyche was “extreme.”

“The Germans could run, but they couldn’t hide,” Wilkinson reported. “Nobody was safe from the Wooden Wonder.” Not even the Luftwaffe chief, Hermann Göring himself.

On Jan. 30, 1943, three Mosquitos famously mounted a daylight raid on the main Berlin broadcasting station, precisely timed to arrive just as Göring—who’d overseen creation of the hated Gestapo—began an 11 a.m. radio address commemorating the Nazis’ 10th anniversary.

The broadcast was rescheduled, but not before sounds of the attack aired over German radio. At 4 o’clock that afternoon, more Mosquitos interrupted a broadcast by the Nazi propaganda minister, Josef Goebbels.

They were largely nuisance raids, and they infuriated Göring, whose frustration with his own Luftwaffe mounted as its dominance in the skies over Europe slipped.

“It makes me furious when I see the Mosquito,” he once said. “I turn green and yellow with envy. The British, who can afford aluminum better than we can, knock together a beautiful wooden aircraft that every piano factory over there is building, and they give it a speed which they have now increased yet again.

“What do you make of that? There is nothing the British do not have. They have the geniuses and we have the nincompoops. After the war is over I’m going to buy a British radio set—then at least I’ll own something that has always worked!”

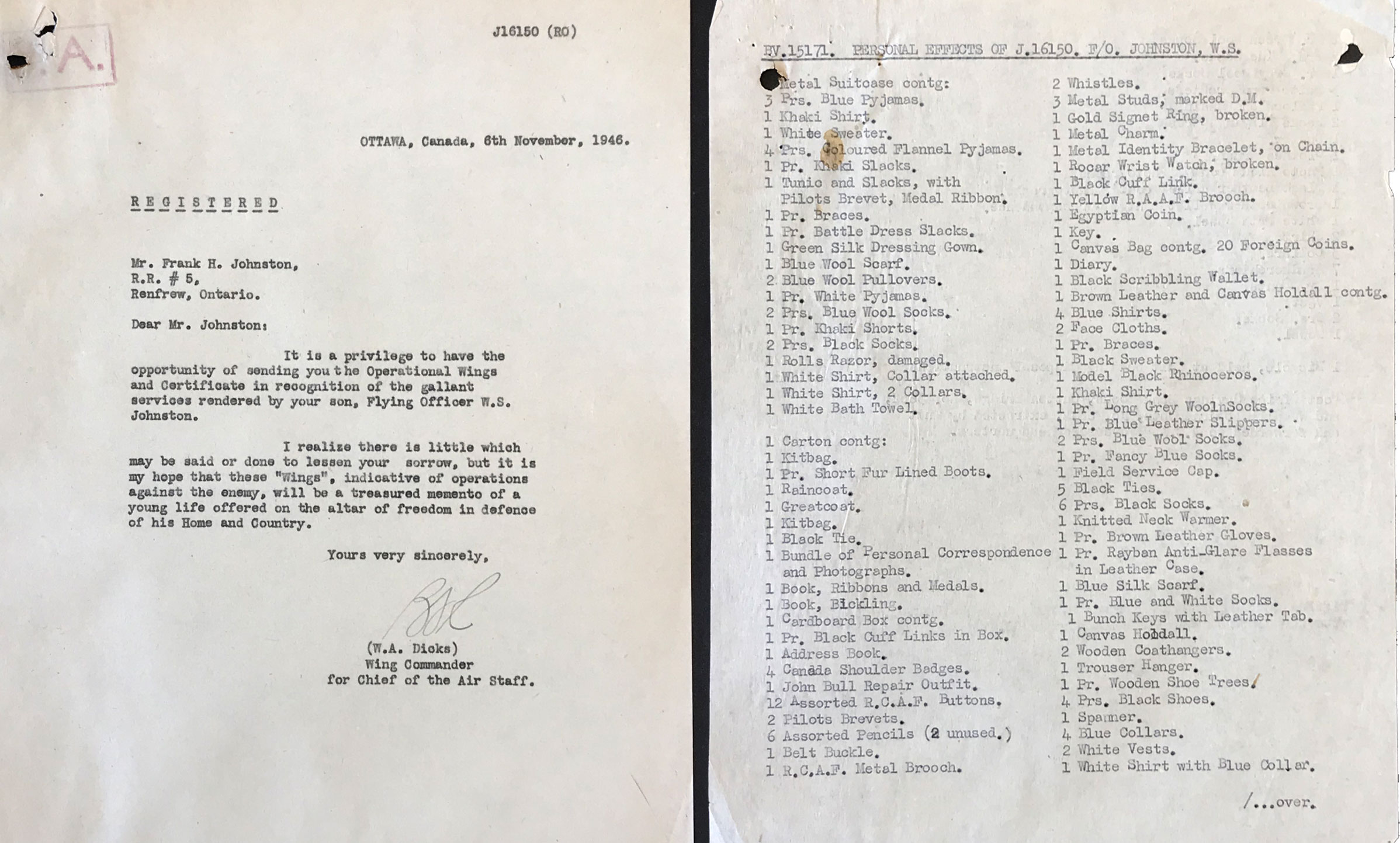

Johnston didn’t have a radio set, but his list of personal possessions ran in two columns over a page and a half. They included some signature aviator kit: Ray-Ban “anti-glare glasses” in a leather case, brown leather gloves and a blue silk scarf. There were two packs of playing cards, a photo album, a diary. And this: “1 bicycle, held at Unit pending disposal instructions.”

Frank Johnston asked that his son’s clothing and uniform be donated to the Officers’ Kit Replacement Bureau in London. The bicycle, presumably, stayed in England.

Johnston’s father wrote the air force again in November 1944 asking if any aircrew had survived the incident and, if so, could he get contact information for them or relatives of the dead. There was no reply in the official record.

It would be more than eight years before the Johnston family received final confirmation that their son’s remains would not be found, despite the fact the plane went down less than two kilometres offshore at midday.

The letter to Johnston’s 76-year-old mother, dated June 6, 1952, informed her “with reluctance that…it must be regretfully accepted and officially recorded that he does not have a ‘known’ grave.”

“I realize that this is an extremely distressing letter and that there is no manner of conveying such information to you that would not add to your heartaches,” said the letter, initialed for Wing Commander W.R. Gunn, RCAF Casualties Officer.

“I am fully aware that nothing I may say will lessen your great sorrow, but I would like to express to you and the members of your family my deepest sympathy.”

Johnston’s name is among the Second World War dead engraved on the cenotaph in front of the Renfrew town hall. FO William Smith Johnston also appears on Panel 246 of the Runnymede Memorial overlooking the Thames River in Surrey, England. Along with Alderton and Hocking, Johnston’s name is among 20,450 Commonwealth aircrew of the Second World War with no known graves memorialized on its stone panels, 3,050 of them Canadians.

Chaiet is memorialized at Ardennes American Cemetery in Neupré, Belgium.

Advertisement