Canada’s most up-to-date aircraft in 1939 was the Northrop Delta, manufactured under licence by Canadian Vickers Ltd. in Montreal.

It was about the size of a de Havilland DHC-3 Otter—a large, single-engine, low-wing monoplane, powerful and fast. Although noisy and said to be nose-heavy, the Delta was a versatile aircraft and pilots generally spoke well of it.

The first all-metal plane built in Canada, the Delta could be fitted with floats, skis or wheels. Three of 20 were delivered to the Royal Canadian Air Force in the fall of 1936 and began photographic survey work the following spring.

As war clouds gathered over Europe in 1939, the Deltas shifted focus to the U-boat hunting grounds off Atlantic Canada. Ted Doan and Dave Rennie were among the aircrew transporting six of the aircraft from Ottawa to their new base in Sydney, N.S.

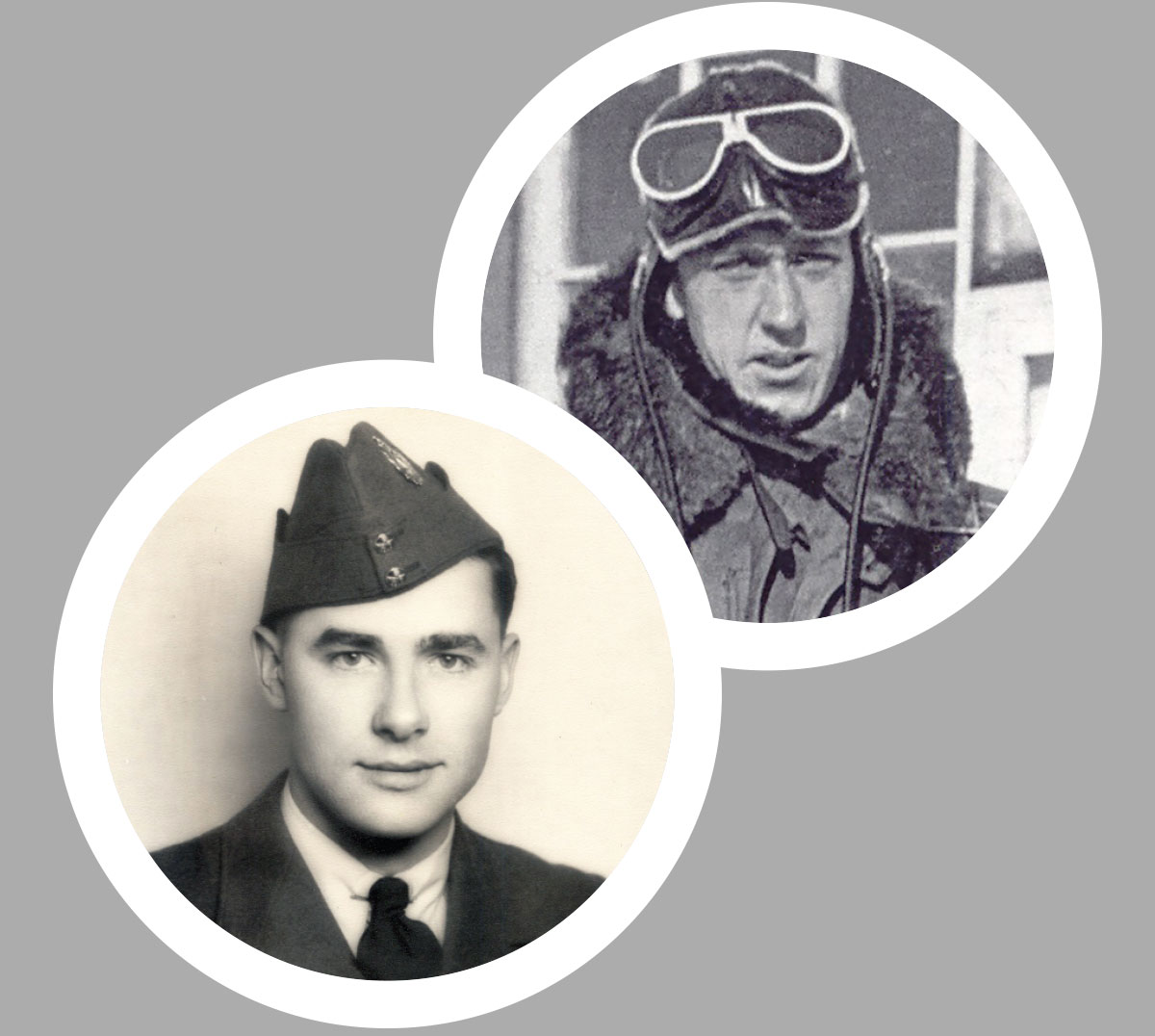

Warrant Officer Class II James Edgerton (Ted) Doan had been flying aerial photography planes in Northern Canada for several years with No. 7 and then No. 8 General Purpose Squadron (which became No. 8 Bomber Reconnaissance Squadron in 1939).

Corporal David Alexander Rennie was an aero-engine mechanic with No. 1 Aircraft Depot in Ottawa. He was transferred to No. 8 effective Aug. 27, 1939—the day the squadron left for Nova Scotia. The pair had never met before.

Rennie had enlisted in 1937. He was known as a reliable, hard worker. His promotion to corporal was effective Sept. 9, 1939—five days before he disappeared.

Doan began his air force career as a fitter apprentice. He joined the RCAF in hometown Vancouver, and was posted to Camp Borden in Ontario in 1927. The service was still in its infancy. The airplane had only been in existence for 24 years and Doan was just 22 at sign-up.

He began flying in 1929, earning his wings and sergeant’s stripes in 1930. He logged hundreds of hours flying most aircraft types then available in Canada.

His last assessment before he was promoted to warrant officer ranked his technical abilities as “very impressive” and his last three assessments as “superior.” “A reliable pilot,” No. 8 Squadron Leader W.W. (Bill) Brown wrote. “A conscientious N.C.O.”

On Aug. 25, 1939, Doan and Rennie were in fine shape. They were young, well-trained, and ready to serve the cause of liberty. Unfortunately, their service would be brief.

It was raining the night of Aug. 26 when Lillian Watterson drove Rennie, her boyfriend, to Rockcliffe Air Force Station in Ottawa. Accom-panying them was her sister Edna and Rennie’s sister Ella.

Before saying goodbye, Ella asked a favour of her only brother. She gave him two letters to deliver or mail when he arrived in Nova Scotia. One, to her future husband, contained her picture.

Doan lived in Ottawa with his wife Vera and two boys—Charles, four, and Lionel, two. He reported early on Aug. 27 for briefing and final preparations. The six pilots were informed that their final destination was to be Sydney, where they would spend their tour of duty searching for enemy submarines off northeast Nova Scotia.

The pilots were to land at the Shediac, N.B., seaplane base for refuelling, then fly on to Sydney. The trip was about 1,530 kilometres, or just over six hours’ flying time. They would maintain a cruising speed of 240 kilometres an hour at 900 metres, arriving in time for supper.

The six planes were just past Millinocket, Maine, when Doan’s Delta 673 dropped out of the group and began descending to Salmon Stream Lake. Cpl. Guy LaRamée, a crewman in Delta 671, recalls 673 had some power during the forced landing and taxied to shore.

Delta 673 had no radio. In 671, LaRamée and his pilot, Flight Sergeant W.C. Pate, followed the disabled plane down to the lake. Once 673 stopped, 671 landed and taxied up alongside. All four men were experienced aircraft mechanics, or “fitters.” After checking the engine, they agreed that a cylinder would have to be replaced before the plane could be flown 27 kilometres to a seaplane base at Norcross. They concluded that the entire engine should be replaced as soon as possible.

Pate and LaRamée stayed the night with Doan and Rennie at a nearby hunting lodge before flying on to Shediac.

The new cylinder arrived from Sydney on Aug. 29 and was installed by mid-afternoon the next day. The men threw their sleeping bags and gear aboard and flew to Norcross, where they found better food and accommodations at the Norcross Hotel.

Doan submitted a standard form to the operations manager at Rockcliffe, citing an overheated engine caused by a “faulty muff installation.” He said he would install a new engine and “if the engine continues to overheat” he would also “replace the muff.”

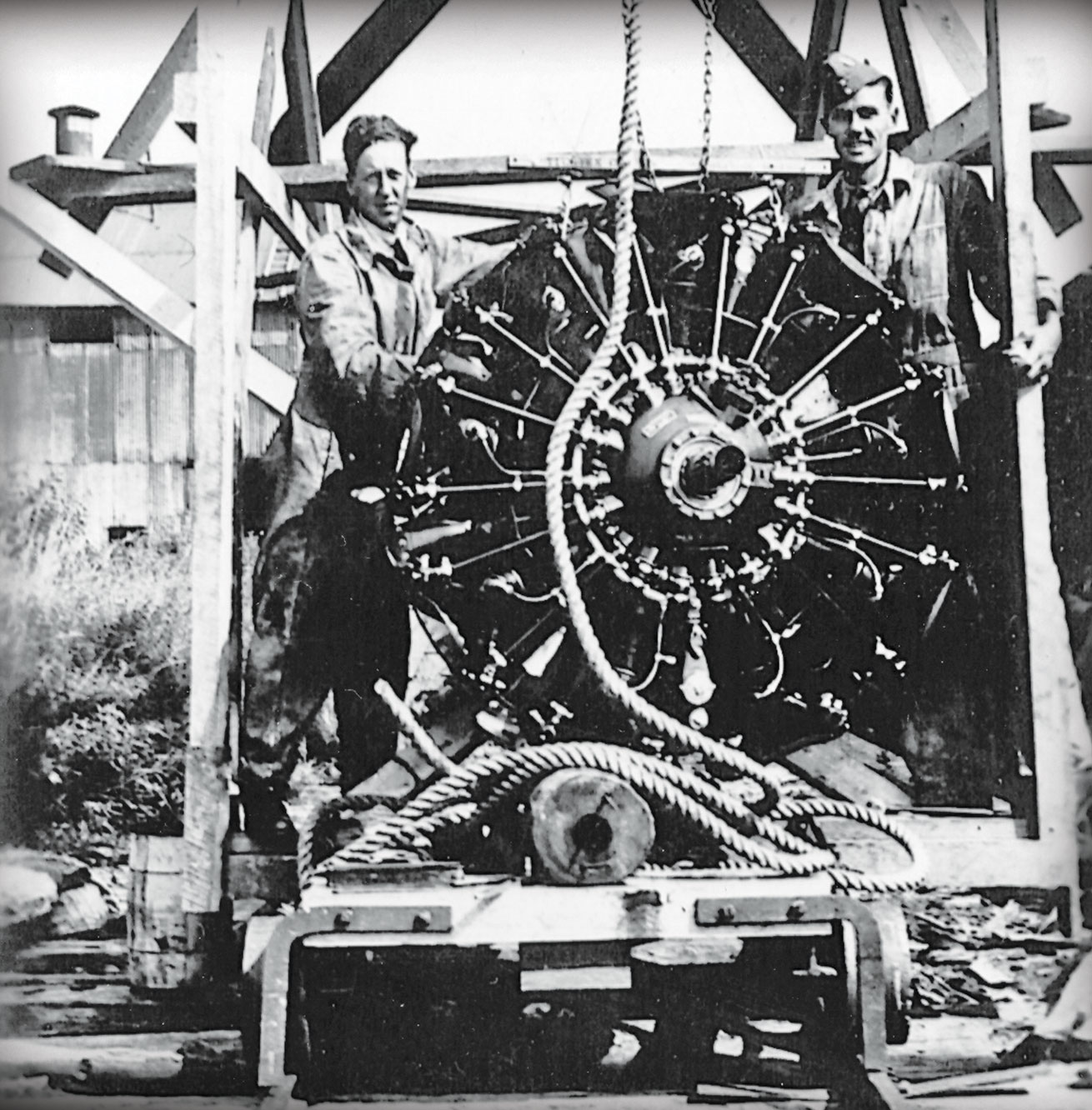

The muff heater on the Delta’s Wright Cyclone 1820 engine is a simple heat exchanger. It uses exhaust heat to preheat air going to the carburetor, thus preventing potentially disastrous icing. The muff heater can also direct heat to the cabin.

Essentially a collection of baffles and sheet metal surrounding the engine exhaust pipes, the muff is nonetheless an important part of the power plant assembly. The Airframe and Power Plant Mechanics Power Plant Handbook says “any exhaust system failure should be regarded as a severe hazard…. Depending on the location and type of failure, an exhaust system failure can result in carbon monoxide poisoning of crew and passengers, partial or complete loss of engine power, or an aircraft fire.”

The problem can be amplified by altitude, temperature and humidity. More than half of exhaust system failures occur within 400 hours, well after installation or maintenance. The “faulty muff installation” could have originated at the factory.

Brown ordered Delta 673 to proceed—via the seaplane base at Lac-Mégantic, Que.—to Ottawa to receive a new engine. Early in the morning of Aug. 31, the men set off for home.

Their delight at the prospect wouldn’t last. No sooner had they taken off after refuelling at Lac-Mégantic when the engine failed again. Once again, Doan managed to bring the big monoplane back down safely, pulling off an even more difficult lake landing after takeoff. The flyers took up residence in the Hotel Lake View, which billed itself as an “ideal rest centre.”

They had little rest. Changing an engine away from the shop is a big job. A new one was to be flown in from Ottawa. They began removing the old engine the next day and settled in, working from morning until night for two weeks.

Still there was no indication the muff would be replaced. Doan must have been convinced the problem was not as serious as previously believed, or that they had fixed it.

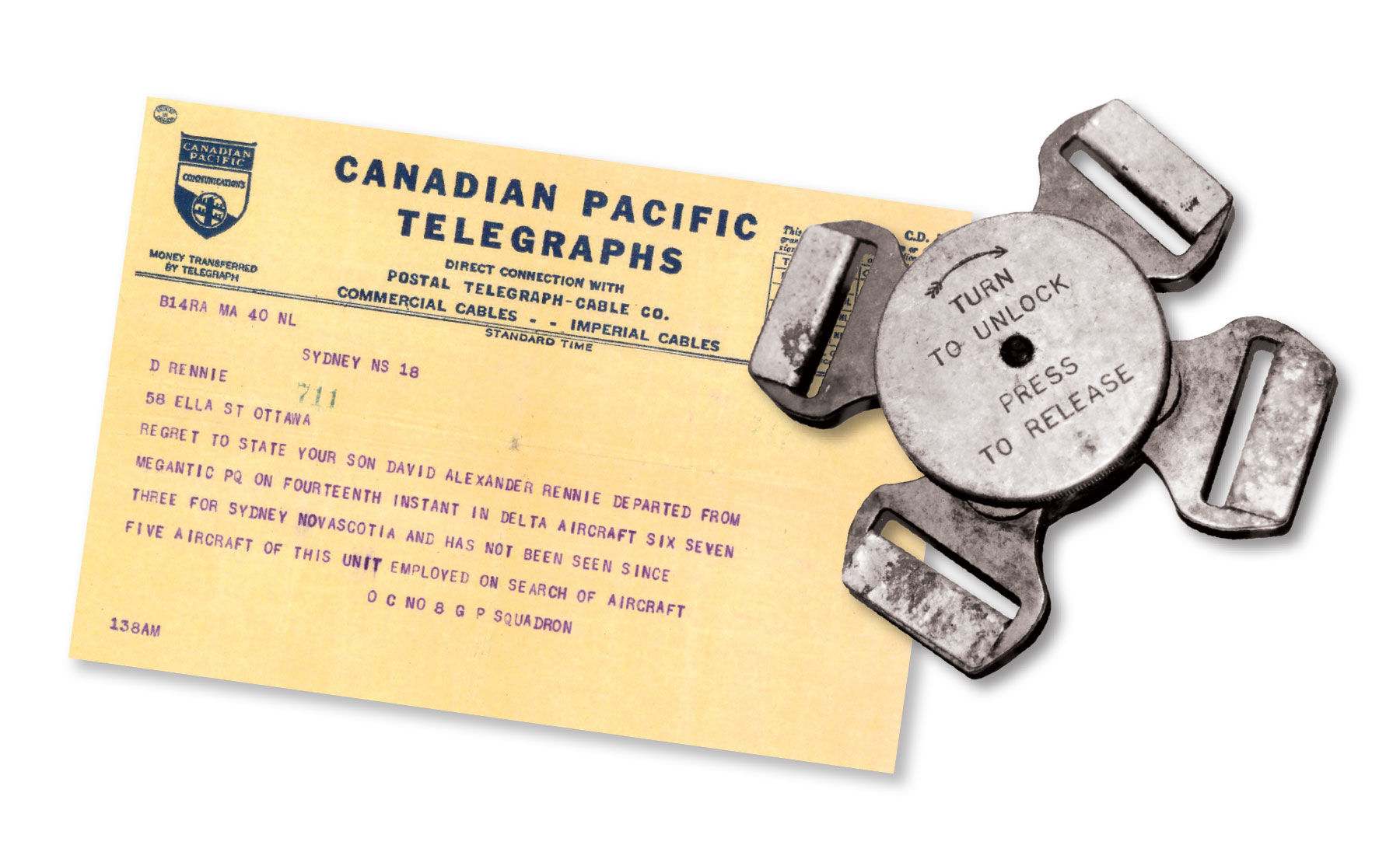

“Tell Ella that the letters have not been delivered,” Rennie wrote his mother, “and who knows maybe they never will.”

The men began testing the new engine on Sept. 13. At first, they idled the big radial. Adjustments were made and, when everything met their approval, Doan began taxiing around the lake. Eventually, he brought the engine to full throttle and took to the air.

After the brief flight, they checked for leaks and prepared to leave. Now Doan was to proceed to Rivière-du-Loup, head southeast to Grand Lake, N.B., then turn to Shediac for refuelling before flying the final leg to Cape Breton.

Squadron Leader Brown had good reason to instruct 673 to head for Sydney by way of Rivière-du-Loup instead of taking the shorter route across Maine. Canada had declared war on Germany on Sept. 10, but the United States would remain officially neutral until the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor in December 1941.

Doan was concerned about crossing too much wilderness without water on which to land. In a letter to his wife written at Lac-Mégantic, he says that from the lake to Montreal is “a mighty dry hop” and thus “it is better [the engine] played out where it did.”

Concern about an engine failure over waterless terrain is likely why Doan flew north from Lac-Mégantic to intercept the Saint Lawrence River just below Quebec City, then followed it to Rivière-du-Loup. It would have been shorter to fly directly, but also riskier.

There were several sightings of Delta 673 after it left Lac-Mégantic, all consistent with the plane’s route, as well as timings and weather. Some said it had been raining, and records indicate eastern Quebec was partly overcast with occasional showers on Sept. 14.

From Plaster Rock, N.B., Delta 673 proceeded toward Grand Lake about 190 kilometres away. The pilot planned to turn the plane over the big lake and head almost due east to Shediac on the coast, a base for transoceanic flying boats and an RCAF refuelling and mooring station. Delta 673 would never arrive.

At the inquiry into the disappearance, an officer said Doan “was not unfamiliar with the route.” Doan had flown over New Brunswick several times and was, according to Brown, “a very reliable pilot.”

The inquiry’s first witness, Flt. Sgt. R.I. (Bob) Thomas, testified that Doan “made a practice of always pinpointing his progress on his map whenever engaged in cross-country flights.”

His practices suggest the pilot would have known exactly where he was. He had entered a 64-kilometre “dry zone” in which there was almost no body of water large enough to allow a safe landing. One exception was Beaverbrook Lake—just big enough to accommodate a Delta on floats.

The lake is about 30 kilometres by road north of Juniper, the last outpost before the vast wilderness tract of central New Brunswick. The entire area is owned by J.D. Irving Ltd., New Brunswick’s largest forest company.

Just a little over a kilometre long and only about 500 metres wide, Beaverbrook Lake lies in a slight east-west depression. On the north side of the lake is a hill. Leading to the lake from the west side is a valley about three kilometres long.

It was over this little valley that now-WO2 Doan (his promotion was effective on this day) prepared to make a forced landing shortly after 2 p.m. It is possible they were losing power and altitude before the engine actually quit. It would miss or sputter along with overheating, especially from a heater/carburetor problem. The descent would have been gradual until the propeller stopped. The plane would then have plummeted out of control quickly if it was already near the stall speed.

Doan had two options: a controlled crash landing, in which he would pull the steering yoke back just above the forest canopy so it would hit the trees belly-first and nose-up; or the second option, which was to stretch the glide and attempt a lake landing.

He chose the latter, believing the big Delta had enough speed and altitude to make it.

But Doan had to land with the wind and not into it. The latter would have allowed a slower, and possibly more survivable, landing speed. He also lost altitude when he turned to line up with the lake.

By the time Doan had the plane set up for landing, he was probably only about 300 metres above the trees and three kilometres from the lake. The plane was sinking fast. The two men could see the water clearly through the windshield as they glided silently toward the safety of its surface.

About a kilometre from the western end of Beaverbrook Lake, and probably 100 metres above the forest, Delta 673 slowed to aerodynamic stall speed. It was a pilot’s worst nightmare. They were now flying so slow that there was no more control.

At this point, the big plane either flipped on its back and plunged inverted into the trees, or Doan took the only action available: push the yoke forward to force the nose down and thus gain air speed. By this time, however, the yoke was sloppy and almost unresponsive. When he did finally get the nose down, it was too late to pull it back.

The plane went right into the trees. From stall to impact was probably no more than four seconds.

The force of the 2,700-kilogram plane hitting the ground was devastating. It blew the doors off, broke all the windows, severed the wings, tore the engine completely off the fuselage and flattened the cockpit. From the engine to the front seats there was nothing but a jumble of crumpled, jagged metal. This is what killed the pilot and his crewman instantly and, in all likelihood, ejected their bodies.

Evidence at the site points to a low-altitude, relatively low-speed, stall-induced crash. There was no crater, no fire, and no debris field. The plane was in one place in several large identifiable pieces. The propeller blades were bent straight backward, clearly indicating it came in with a dead engine. Except for the snapped top of one tree, there was no debris trail or swath of broken trees. The exact cause of the engine failure cannot be determined with certainty. It is safe to conclude, however, that it was related to a muff heater/carburetor problem.

Sadly, had the men been able to fly across Maine and not around it, all things being equal, the engine problem would have occurred over the lakes region near Fredericton.

A search was organized the following day.

Thursday, Sept. 15, was Ted and Vera Doan’s fifth wedding anniversary. Vera had just baked cookies when a Canadian Pacific Telegraphs delivery boy arrived at her door. The telegram was brief:

Sydney NS

Regret to state that your husband departed from Megantic PQ in Delta aircraft six seven three on fourteenth for Sydney Nova Scotia and has not been seen since. Five aircraft of this squadron employed on search of aircraft

OC No 8 GP Squadron

Vera had just sent Ted the last letter she would ever write him. Dated Sept. 9, it arrived in Sydney the day he disappeared.

“Our dear Daddy and Husband,” it began. “I am hoping and praying that you won’t have to cross the ocean, Dear. But I’m sure everything will turn out alright and we’ll soon be together again.”

Four to five planes traced and retraced the route flown by Delta 673. Investigators followed up on “reports and rumours.” It eventually became evident the plane had come down in woods and not on water.

The crash area was in a mostly coniferous forest where there was no fall foliage to drop and the canopy was fairly dense. The crash site was compact, with no obvious indicators of what had occurred. In fact, search aircraft actually flew over it several times. After seven weeks and 400 flying hours, the search for Delta 673 was terminated at the end of October.

In a letter dated Oct. 26, 1939, Air Vice-Marshal George Croil told Doan’s parents “they may have flown out over the sea where, if they were forced to alight, the aeroplane would probably sink under the conditions of heavy sea which are reported on the day in question.”

The plane remained undiscovered for almost 19 years.

Time went by and many changes took place. The forest around Beaverbrook Lake, which had not been harvested since about 1920, now belonged to the Irving company. By 1958, the forest products company was preparing to upgrade old logging roads before clear-cutting and replanting the surrounding woodlands.

July 1958 came in hot and humid. On July 10, Irving employees Frank Barkhouse and Charlie Grey were surveying a new road. An Irving plane was flying the proposed route to advise the crew of any obstacles. Suddenly, the pilot noticed something shining through the trees. He circled around and saw the reflection again. He flew lower but could not identify it. Thirty kilometres back in the wilderness, the pilot knew that whatever it was it should not be there. He radioed Barkhouse and Grey, then guided them through the dense woods.

To their disbelief, in a stand of softwood trees was the wreckage of a vintage airplane. Eighteen years, nine months and 26 days after it disappeared, the mystery surrounding the disappearance of Delta 673 was solved.

Next morning, RCMP Cpl. Ron Rippin and ranger Stuart Cougle took the forest-service jeep and headed to Juniper. Ten-year-old Jim Cougle was informed, over much protestation, that his presence would not be required. The two men picked up Grey and Barkhouse and headed back to the crash site.

The four found pieces of equipment and rotted clothing aboard, but no human remains. Around the plane, they located the remnants of a briefcase with part of an Ottawa newspaper dated Sept. 13, 1939.

“The left side door…was wide open and there was abundant evidence of porcupine intrusion—anything wooden (except a treated wooden box that held a bombsight) had their teeth marks on it,” Rippin recalled.

The searchers found belt buckles, a wallet containing only a calendar, brass buttons, parachute harness buckles, a camera and unopened rations. They also found part of a suitcase bearing the initials D.A.R. In a rear compartment, they found an unopened first-aid kit. A razor, flashlight, bayonet and some coins were also returned to the Rennie family. Barkhouse mentioned a particular item found at the site: “a tattered picture of a girl.”

Ella Bateson, Rennie’s sister who had given him the letters to mail, remembers the day the story broke.

“We had planned a family picnic that day,” she said. “We were going on a campout but I had a funny feeling that bothered me so much. I couldn’t go with the others, although I had planned to, but I just didn’t feel right about it.”

She stayed at home and later heard over the radio of an RCAF plane discovered in the New Brunswick wilderness. She knew immediately that it was the plane that took her brother to his death.

Vera Doan was at home in Toronto, also listening to the radio. During a mid-morning newscast, she learned that an old airplane had been located in the woods of New Brunswick. She turned to son Charles and said: “This is Ted’s plane.”

“A thorough search of the aircraft and surrounding area revealed a watch belonging to your husband’s crewman, Corporal Rennie, and other articles which could not be individually identified,” wrote Air Vice-Marshal J.G. Kerr in a letter to Vera Doan dated July 30, 1958. “The articles found would indicate that it was very unlikely that either your husband or his crewman left their aircraft or survived the initial impact…. The search failed to reveal any trace of the remains of the crew and I can only regrettably and respectfully suggest that lapse of time and elements have precluded their recovery.”

John Lockhart, a well-known physician from Bath, N.B., subsequently discovered what the others had missed: Inside the cabin he found fragments of “temporal (skull) bones.” Evidence suggested both men died instantly of massive head injuries.

The wreck of Delta 673 was left untouched until 1969, when the RCAF decided that, because it was the first aircraft lost after the war declaration, it should be preserved in the Canada Aviation Museum in Ottawa, at the site where it began its final journey.

The air force dispatched a crew to recover the wreckage. Only the fuselage made it to Ottawa, where it remains in storage. The rest of the plane was lost, including the engine which may hold the answer to why it crashed.

But Doan and Rennie have not been forgotten. Their names appear first on Canada’s Second World War Roll of Honour.

Advertisement