The Newfoundland Regiment was

the only North American military unit

to fight in Britain and France’s costly

Gallipoli Campaign in the twilight

of the Ottoman Empire

Not long after landing in Gallipoli in September 1915, the Newfoundland Regiment found itself stalled in trench warfare, constantly harassed by sniper fire.

In particular, Major T.M. Drew, the acting commanding officer, had noticed a Turkish sniper firing from a small knoll midway between the opposing trenches. The enemy took his spot at dusk and waited for night to pick his targets, then left before daylight. Drew gave an order to rid the regiment of this menace.

Lieutenant J.J. Donnelly was detailed to lead six men and a non-commissioned officer to an abandoned post hidden from enemy view in the afternoon of Nov. 4. This time it was the Newfoundlanders’ turn to wait.

As daylight faded, not one, but three Turkish snipers started to make their way to their position. As they were challenged by the Newfoundlanders, a firefight broke out and two snipers were killed. The third returned fire and wounded one of the Newfoundlanders.

A second patrol led by Lieut. H.H.A. Ross went to reinforce Donnelly but stumbled on a Turkish patrol attempting to encircle Donnelly’s group in the dark. A second firefight erupted. Private James Ellsworth was killed, while Ross and others received slight wounds before forcing the enemy’s retreat. By daylight, the Newfoundlanders’ position was reinforced and christened Caribou Hill after the emblem on the regiment’s badge.

Before the end of the year, Donnelly received the Military Cross and two others received the Distinguished Conduct Medal for their actions that night.

Finding Caribou Hill

“For a long time, historians thought that the original Caribou Hill was inaccessible,” historian Frank Gogos told a delegation from Newfoundland visiting Turkey in September. “The regiment left Gallipoli and no markers remained to say where it was.”

But Gogos has been working with old maps, handwritten notes and archives. With the help of a topographer at Memorial University in St. John’s, he determined that one of the roads in today’s Gallipoli Peninsula Historical National Park intersects with the hill.

Gogos guided the bus carrying the delegation and another with members of today’s Royal Newfoundland Regiment to the spot he had pinpointed. The group began its own exploration of the area, finding the remains of a small building. One of the soldiers discovered a rifle shell casing among the dirt and weeds.

“It could have been a .303 shell or a [Turkish] Mauser 7×57-mm round. There is only one millimetre separating them,” said Gogos. The spot may or may not have been the site of the heroic actions 100 years earlier, but Gogos is confident he has evidence to prove it is.

The discovery of the famed Caribou Hill was a highlight of the pilgrimage by members of the Royal Newfoundland Regiment Advisory Council (RNRAC), a volunteer non-profit organization designed to foster support of the regiment and its history, and Honour 100, a directorate within the Newfoundland and Labrador government’s Department of Business, Tourism, Culture and Rural Development. Heading the delegation were RNRAC Chair Ron Penney and Deputy Minister Alastair O’Rielly. Also along were former Newfoundland and Labrador lieutenant-governor John Crosbie and his wife Jane. As a lieutenant-governor, Crosbie is automatically an honorary colonel of the regiment.

The discovery of the

famed Caribou Hill

was a highlight

of the pilgrimage.

Three of the pilgrims were direct descendants of those who fought at Gallipoli: Neil Harvey, a doctor from Grand Falls/Windsor, is the son of a veteran who served; Ken Gatehouse of St. John’s, a former provincial secretary of The Royal Canadian Legion’s Newfoundland and Labrador Command and Christopher Morry of Ottawa are both grandsons of veterans who served. Also along were Elinor Ratcliffe, who donated $3.2 million toward an exhibit on the regiment at The Rooms, the province’s archival collection, and John Perlin, a former Canadian Secretary to the Queen. Others, such as Reginald Snow and Terry Hurley, are veterans of the regiment.

The group travelled from St. John’s and elsewhere in Canada and the United Kingdom and arrived in Istanbul, Turkey, on Sept. 15. After a few nights in Istanbul, they moved to a hotel in Eceabat, 300 kilometres to the west on the Gallipoli peninsula.

The Dardanelles Strait, which separates Europe on the Gallipoli side from Asia Minor on the other, has been strategically important since ancient times as it leads to the Sea of Marmara and Istanbul. It was important to Britain in the First World War because it was the only way to get supplies from the Mediterranean Sea to the Black Sea and on to Russia. The strait remains important today as the only way Russia’s navy can pass into the Mediterranean Sea. These days, of course, Turkey is our ally and a member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization.

The first official ceremony of the trip took place on the morning of Sept. 19 to commemorate the fateful night when the regiment came ashore in Gallipoli. The delegation was joined by an honour guard from the regiment on a windswept point on Cape Helles, where British and French forces landed in 1915. The Helles Memorial is a 30-metre-high obelisk commemorating 20,885 Commonwealth soldiers and sailors from the First World War who have no known graves. The names are carved into white stone. The Newfoundland Regiment is commemorated as part of the “unallotted troops.”

“In 1914, the Dominion of Newfoundland was an independent country,” said Penney, “and in what has been described as our first national effort, it raised a regiment and supported it for the four long years of the First World War. More than 6,000 Newfoundlanders joined the regiment and more than 12,000 participated in the war effort as members of other forces, at sea and on land. More than 1,500 of them paid the ultimate price.”

Only 60 years earlier, the Ottoman Empire

had been Britain’s ally in the war against the Russians.

As the wind blew around the monument, a bugler from the regiment played “Last Post,” followed by silence and “The Rouse.” Melanie Martin, the leader of the Honour 100 project, then led the audience in the “Ode to Newfoundland,” the official provincial anthem. Major Shawn Samson, the regiment’s padre, gave the benediction.

The delegation remained in Eceabat for five days for commemorations at nearby war cemeteries, immaculately kept by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC), and to visit the beaches where the regiment came ashore and distinguished itself during evacuations, not once but twice.

Opening another front

By the spring of 1915, the war that some had hoped would be over by Christmas 1914 had stalled into static trench warfare on both the Western and Eastern fronts. There was an argument around the British war cabinet that a new front was needed to drain enemy forces away from the Western Front so that a real breakthrough could occur.

Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the British Admiralty, was in favour of a naval offensive through the Dardanelles Strait and on to capture Istanbul, then known as Constantinople, and force the Ottoman Empire out of the war (“Face to Face,” November/December). The move would also allow the Allies to get supplies and weapons into Russia for the fight on the Eastern Front.

As the last soldiers

pulled away on the night

of Jan. 9, 1916, they

detonated abandoned

magazines on shore,

having again successfully

deceived the enemy

about the final departure.

Only 60 years earlier, the Ottoman Empire had been Britain’s ally in the war against the Russians in the Crimea. With the turn of the century, Russia was now Britain’s ally, while the Germans had invested heavily in a mostly agricultural empire. Germany had built the Orient Express railway and a magnificent station in Istanbul, but by 1914 the Ottoman Empire was crumbling, having lost much of the land it once controlled in Europe and Africa. When war came, it threw its support behind Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Reluctantly, the British cabinet agreed to the Dardanelles offensive. When the Royal Navy began its attack on March 18, 1915, Turkish forces manning mountaintop fortifications opened fire on it. Three ships were lost to mines and artillery fire. The ships had to withdraw. For the attack to succeed, the fortifications would have to be taken by the army.

On April 15, 1915, British forces, along with the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps, fought their way ashore on five beaches around Cape Helles on the southern tip of the peninsula. The goal was to capture Achi Baba on the high mountainous portion of the peninsula. Confident after its victory in the navy encounter, the Ottoman Empire deployed its army to resist the invaders. Ironically, many of the fortresses used by the Turks had been reinforced by British forces in the 19th century.

The Allies struggled to reach the high ground, but soon found themselves, like their comrades in northwest Europe, bogged down in trench warfare.

The 1,076 soldiers in the Newfoundland Regiment were sent in on the night of Sept. 19-20, landing at Suvla Bay. Moving from HMS Prince Abbas onto landing craft called lighters, the regiment made it ashore under cover of darkness, but when morning came they were soon spotted and shooting and shelling began. On Sept. 22, Pte. Hugh McWhirter, 21, became the first member of the regiment killed in battle. The next day, a sniper killed Pte. William Hardy, 22.

By the end of the month, the regiment had taken over a 1.5-kilometre stretch of the British front line. At times they were only 50 metres away from the Turkish lines. The routine was four days in the trenches, then eight days in the rest dugouts, then back for four days. As the months passed and the ranks were depleted, the men were forced to spend eight days in the trenches and four days in the dugouts.

Conditions were terrible, with insects so thick they covered everything a soldier could eat. The nights were cold and November brought a storm that flooded the trenches and left many with frostbite.

In the meantime, Bulgaria joined the Central Powers—Germany, Austria-Hungary and Italy—and Serbia was in grave danger of invasion. If it fell, Germany would have uninterrupted railway service to Constantinople and could send artillery to outmatch the Allied forces.

On Nov. 23, Britain’s cabinet agreed to a complete evacuation of the peninsula. The regiment began to evacuate its sick members. Then, trench tools and surplus kit were sent down to the beaches. Finally, the men were evacuated over two days. The navy supported the evacuation by shelling new areas to distract the Turks. Meanwhile, a rearguard from the Newfoundland Regiment set about making the Turks believe the regiment was still present in full force. Unmanned rifles were set up with a can of sand on the trigger. A leaky can of water was placed above the can of sand. When the combined weight of the sand and water reached seven pounds, it pulled the trigger, making the Turks think a sniper was at work.

There was not a casualty in the whole evacuation. The regiment arrived on the island of Imbros, 15 kilometres away, thinking it was getting a well-deserved rest, but within two days, it was ordered to return to evacuate Cape Helles. This time the regiment arrived at W Beach, now known as Lancashire Landing.

The regiment took over former British trenches and made them as comfortable as possible. Christmas was celebrated with an extra shot of rum to go with the usual bully beef and biscuits. When the evacuation of Helles began, the Greek labourers hired for the transfer balked at being shot at by snipers and the Newfoundlanders found themselves taking over the stevedore duties of getting supplies to the awaiting ships.

Again, members of the Newfoundland Regiment stayed behind as a rearguard to convince the enemy that the lines were still defended. As the last soldiers pulled away on the night of Jan. 9, 1916, they detonated abandoned magazines on shore, having again successfully deceived the enemy about the final departure.

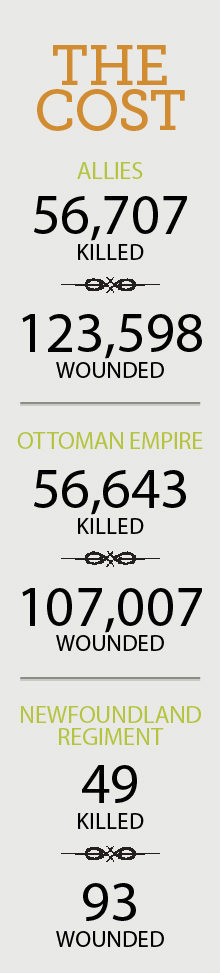

The whole Gallipoli conflict had cost the Allies 56,707 killed and 123,598 wounded, while the Ottoman Empire suffered an almost equal 56,643 dead and 107,007 wounded. Veterans Affairs Canada puts the final tally for the Newfoundland Regiment at 49 dead and 93 wounded.

Commemorations on land and at sea

The wind-blasted ceremony at the Helles Memorial was also attended by Beker Dag, vice-governor of Çanakkale, one of Turkey’s 60 provinces. Çanakkale includes both sides of the Dardanelles Strait and even the ruins of ancient Troy.

To reciprocate his visit, the delegation moved to the Turkish Memorial, a mammoth structure with four columns easily seen by any ship entering the Dardanelles. It is dedicated to 250,000 Turkish troops who took part in the battles. The columns are decorated with bas-relief scenes from the battles, and a cemetery where some 500 Turks are buried is nearby. Giant statues line the entrance.

Speaking in Turkish, Dag echoed the words of the great Turkish hero Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. “Those heroes who shed their blood in the territory of this country, you are in the soil of a friendly country. Here, therefore, rest in peace. You are lying together with the Mehmetçik [Turkish soldiers] side by side, in each other’s arms. You, the mothers, who sent their sons from faraway countries, wipe away your tears, your sons are now in peace and will rest in peace, here forever. After losing their lives on this land, they have become our sons as well.”

After a simple wreath-placing ceremony, the Turkish officials joined the regiment at a luncheon hosted by the Honour 100 directorate.

Following lunch, the delegation joined the regiment in a service at Lancashire Landing Cemetery, not far from W Beach, where the 1st Lancashire Fusiliers landed on April 25. They came ashore under heavy fire and still managed to take the surrounding cliffs. Six Victoria Crosses were awarded for actions in the battalion, an achievement publicized as having won “six Victoria Crosses before breakfast.”

Here the Newfoundland pilgrims searched the rows of headstones, looking for the three Newfoundlanders buried in the cemetery. Padre Samson led a short service naming the Newfoundlanders and placing a wreath.

The cemeteries in Gallipoli are quite different from those seen in France, Belgium and Italy. The CWGC still tends them with great care, but here the ground is too soggy to hold the usual Commonwealth headstone. Instead, a pedestal is built with a stone plate on top to mark the graves. A walled cross feature is also used instead of a free-standing Cross of Sacrifice.

The Imperial War Graves Commission, forerunner of the CWGC, did not have access to the cemeteries in Gallipoli until after the war ended. As a result, the commission had to work from maps marking the graves built under battle conditions. The burial places are marked on cemetery plans, but the graves are not marked on the ground. There are many graves that cannot be identified. Often the cemeteries contain large open spaces dotted with known graves. Many of the markers have a name followed by the inscription “believed to be buried in this cemetery.”

The next day, a final ceremony with the regiment was held at Lone Pine Cemetery, a strategically important plateau. Padre Samson again led the simple service of “Last Post,” the silence, “The Rouse” and the singing of “Ode to Newfoundland.”

At the end, Regimental Sergeant Major Wayne Allen addressed the soldiers. “For the first time since 1915, the regiment has come to Gallipoli and paid our respects to the comrades who fought and fell here. It is now time to go home.”

After the regiment departed, the delegation visited Kangaroo Beach, where the Newfoundlanders first came ashore, now a popular spot for fishing and diving. Here, one more simple ceremony took place: O’Rielly, assisted by Penney, dropped a wreath into the waves. When it crashed into the rocks, an obliging diver in a wetsuit gently pushed it out to sea.

Walking along this beach, Neil Harvey remembered his father William Thomas Harvey. “My father would not talk about the war,” he said. Neil, travelling with his son Andrew, learned most about his father’s wartime experiences from Newfoundland’s archives in The Rooms. While serving with the regiment in Gallipoli, his father developed tuberculosis and was invalided to London and ultimately back to Newfoundland. Still, he went on to have a full life. Neil is the youngest of eight children.

Christopher Morry of Ottawa has edited and published the memoirs of his grandfather, Howard Morry. “We found after his death that my grandfather kept a journal. It was just reports on the weather and the tides, but we found that sometimes when he had time, he would start to record his memories of serving in the war.”

Morry was particularly interested in finding the grave of David Carew, who was buried in the Hill 10 Cemetery. “Davy was 16 when he joined the regiment and only 18 when he was here. My grandfather was 31 at the time and Davy stayed close to him, even sharing a blanket at night. He seemed to think being with the older man would keep him safe. However, my grandfather was called away on another assignment. Sure enough, a sniper got him.”

A sixth caribou?

After the formal ceremonies, O’Rielly, accompanied by Penney and Martin, went to Çanakkale, the provincial capital city, to meet with Governor Hamza Erkal. While O’Rielly would only characterize the conversation as positive, there was a particular hope among delegation members.

Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas Nangle, who was padre to the regiment during the First World War, was later Newfoundland’s representative on the Imperial War Graves Commission. Among Nangle’s accomplishments was the creation of the five caribou monuments in France and Belgium that mark the places where the Newfoundlanders served so valiantly in the First World War.

“Nangle wanted six caribou monuments, the last one being in Gallipoli,” said Gogos. “However, after the war, the Ottoman Empire crumbled and Turkey was in civil war. He had no access to Turkey and the monument never was built.”

Perhaps with Caribou Hill properly located, a lone caribou may one day stand on these windswept shores to represent those who came from a tiny dominion and served with distinction.

Advertisement