The Faces to Graves project is collecting stories and photographs of nearly 6,000 Canadian soldiers buried in Dutch cemeteries

Few facts are inscribed on his headstone. He served with the Canadian Provost Corps and died on April 17, 1945, aged 29.

Clarke lived an ordinary life and like so many other ordinary young men who died fighting for their countries throughout the ages, his story ordinarily would have been lost to history.

But Clarke’s story, along with those of thousands of other young Canadians who died in the fight to liberate the Netherlands, is to be preserved for generations to come, thanks to enthusiastic researchers on both sides of the Atlantic.

“By telling their stories, we keep their memories alive,” said Alice van Bekkum, president of the Faces to Canadian War Graves Groesbeek Foundation, which is part of the Faces to Graves project.

The Faces to Graves project is collecting stories and photographs of the nearly 6,000 Canadian soldiers buried in Dutch cemeteries. The stories are posted on a digital monument on the Faces to Graves website. Clarke’s is among the hundreds of stories and photos posted so far.

After the death of his father, Francis Joseph, in 1926, Clarke’s mother Veronica Ann Weir moved young Emmet and his brother and two sisters from Brooklyn, New York, back to the bosom of family in Ottawa.

A skier and rower in high school, Emmet went on to compete on the boxing team at Queen’s University, where he studied mechanical engineering. A photo on the digital monument shows him with a young woman, both carefree and smiling.

In 1940, he enrolled in the Canadian Officers Training Corps, became a second lieutenant and joined the Royal Canadian Artillery. He was five foot ten, had brown hair and blue eyes and weighed 147 pounds when he enlisted.

A photo taken at that time by Yousuf Karsh captures a handsome young man in uniform, gazing with equanimity, it seems, into the future.

In 1943, Clarke was part of the invasion force that fought through Sicily and on to Italy. In early 1945, just before his regiment left Italy for Belgium and the fight to liberate the Netherlands, he was promoted to captain and transferred to the Canadian Provost Corps.

In mid-April, Clarke was in the thick of it. On April 16-17 at about midnight, 1,000 retreating Germans descended on Otterlo, about 25 kilometres southwest of Apeldoorn, unaware the village had been liberated and was the site of 5th Division headquarters.

A Canadian artillery sergeant challenged the approaching men, reported Reuters correspondent Charles Lynch. “The reply was a vicious burst of spandrel fire.… Ten seconds after the Canadian sergeant’s challenge, there was bedlam.” Germans overran the gun emplacement.

“Our own losses were much lower.” But they included Clarke.

They attacked with machine guns, artillery and mortars. Taking the brunt initially were defenders comprised of “the ordinary establishment of a Canadian headquarters…clerks, batmen, drivers, switchboard operators and staff officers,” reported The Canadian Press.

The last major battle in the Netherlands lasted all night. Tanks and flamethrowers finally subdued the Germans. The diary of the 24th Canadian Field Ambulance records that after the battle ended at 8:30 a.m., “400 German dead lay in the fields, ditches and roads and 250 had been taken prisoner from a force estimated to be 1,000 strong.”

The official history of the Canadian Army describes the encounter as a “skirmish” that produced an estimated 300 German casualties. “Our own losses were much lower.” But they included Clarke, who was pronounced dead at about 2 a.m. at an advance casualty station.

He was mentioned in dispatches for gallant and meritorious service. After the war, his mother was sent the medals of the son who would never return to Canada to pursue a career as a mechanical engineer. His godson, nephew Patrick O’Keefe, who was born after Clarke went overseas, never met him.

“I was three or four years old when he died,” said O’Keefe, of Ottawa. “At first the family grieved,” he recalled. “Later, they didn’t really talk about him much.”

O’Keefe grew up knowing little about the uncle for whom one of his cousins was named. The memory of Emmet was fading in newer generations of the family.

It might have stayed that way but for van Bekkum. The idea to collect stories on every soldier buried in the Netherlands began when her curiosity was piqued by a single war grave in the Gorinchem general cemetery.

She discussed her dream of a digital monument.

She researched that soldier’s story, then was drawn to research others. She was inspired by a book about 225 men buried in one Commonwealth War Graves cemetery.

“But for Groesbeek, this is impossible,” she said. No one person could do the research on the 2,619 buried there as well as those whose names are inscribed on the Groesbeek Memorial.

She discussed her dream of a digital monument with Gert Jan van’t Holt, known widely in Canada for his work with Welcome Again Veterans, who began collecting stories and photos of Canadians for the information centre at Holten Canadian War Cemetery in the 1980s.

Bekkum reached out to fellow members of the Liberation of the Netherlands Branch of The Royal Canadian Legion. The Groesbeek foundation was formed in 2015. Not long afterward, the other large Canadian war cemeteries in the Netherlands joined in the project, forming Canadian War Graves Nederland.

“Every name stands for a young man who left his home, his family, parents, wife, children and started an unknown and dangerous journey. That journey ended here in the Netherlands. For our freedom. We are obliged to remember their name and their story,” says the foundation’s policy document.

Also in 2015, history teacher Vanessa Kirtz of Kanata, Ont., assigned research projects on Second World War soldiers whose graves students would visit during a school trip organized for the 70th anniversary of the liberation of the Netherlands.

The reaction of students persuaded her to continue assigning the projects after returning home.

“I used to assign projects on First World War soldiers because the documents were online” and easy for students to research, Kirtz said. After the trip to the Netherlands, she switched to Second World War soldiers.

“Students seemed to have a better connection.… They referred to them as ‘my soldier.’” Students researched military documents, original source material from Library and Archives Canada, old newspaper reports. “We found families, people still alive, who had memories of the soldiers. The students were so engaged.”

Instead of merely studying history, the students were touched by it.

When a second school trip was planned for the 75th anniversary of the liberation in 2020, Kirtz began working with Faces to Graves and assigned students research on soldiers buried in Groesbeek Canadian War Cemetery.

“The First World War projects the students did were beautiful, creative and well done. But nothing further was done with it. Now students know their work will make a difference, that people will read it,” said Kirtz.

Grade 10 student Grace Whitsitt was one of the pair assigned to research Clarke. “I really like history, and this would let me get to know somebody’s story.”

When Kirtz contacted Clarke’s family, the high school researchers got an emotional boost.

“It means a lot to me,” said O’Keefe. “It was an opportunity for me to learn about my uncle. I had seen one or two photographs, but this gave me a picture which I never would have had. I learned quite a lot about him which I didn’t know.”

“It was very rewarding to make this project for somebody who would really appreciate it,” said Whitsitt.

The school trip was cancelled due to the pandemic, so Whitsitt did not get a chance to see Clarke’s headstone first-hand. But Emmet Clarke’s story is now part of the Faces to Graves digital monument. Kirtz estimates 75 life stories by her students will be published on the site by the end of the year, and more in future.

“I’m proud to tell his story and have it seen by people in the public,” said Whitsitt.

“It was mostly young men who sacrificed their lives,” said O’Keefe. “Now the world can learn about them.”

The Defining Moments Canada website has included stories of eight soldiers under its VEDay75 link and resources and suggestions provided by Kirtz for other teachers.

The beauty of a digital monument is that it can be continuously updated and has space to include plenty of information—stories, photos, copies of documents, as well as war history and anecdotes relevant to the soldiers’ biographies.

“I hate to think that they gave everything, and then are forgotten.”

But it takes an army of volunteers on both sides of the ocean. Luckily, the research bug seems to be contagious in Canada.

Calgary nurse Donna Maxwell, who was raised in a military family, visited Juno Beach in 2003, where her uncle landed with the Canadian Scottish Regiment (Princess Mary’s) on D-Day. Since then, she has researched every soldier buried in the Villanova Canadian War Cemetery in Italy, contacted nearly all their families, and researched more than 1,000 buried in Groesbeek and hundreds buried in Holten. Many of those stories are posted on her Soldier Seeker website.

“Some of the stories are so fascinating, you could write a movie,” said Maxwell. “Sometimes, I would be crying over my morning coffee. I hate to think that they gave everything, and then are forgotten.”

Three of her own great-uncles were lost in the First World War but the family knows the gravesite of only one.

“I cannot imagine the pain felt by my grandmother when she lost three brothers. We still are unsure of the regiments and place of interment of the other two boys.”

Her research has become a labour of love.

“I don’t think of it as a hobby,” she said. “It’s my life’s work. Every time I find a picture, it’s like winning a lottery.”

Maxwell intends to keep on researching soldiers’ lives, hopes to get all the information she’s collected over the decades online, and says she is tempted to begin researching soldiers in other Italian cemeteries.

Retired Dutch diplomat Pieter Valkenburg emigrated to Prince Edward Island, became a Canadian citizen and caught the research bug in 2016 during a Legion Remembrance Day ceremony. He got a second dose after a trip to the Netherlands during which he visited the information centre at Holten and met van Bekkum, offering to help both with their projects.

He set out to put a face to each of the 48 names on the Borden-Carleton Cenotaph, but his work quickly expanded to include Prince Edward Island soldiers, then soldiers from the Maritimes and then across Canada. He also posted several videos on his “On the War Memorial Trail” research project on YouTube.

Now he is searching for stories and photos of Indigenous soldiers; at least 55 are buried in Dutch cemeteries, he said, maybe more, including William Daniels, a Cree from Sturgeon Valley, Sask., and Stanley Owen Jones, a Haida Nation member from Masset, B.C.

Daniels was killed in action with the Royal Winnipeg Rifles in April 1945. Jones also died in 1945 when a track came off a carrier and overturned in a ditch, trapping him under the water.

“It’s a tremendous honour for me to do this,” said Valkenburg, who was raised with the Dutch reverence for their liberators. But he has another motivation.

“It makes me sad seeing First World War monuments with all those names and nobody knows anything about them anymore.” Consequently, he wants to capture as many stories of Second World War soldiers as he can.

It’s also part of what motivates retired journalist Kurt Johnson of Renfrew, Ont.

“Every Remembrance Day we say: ‘We will remember them.’ We say that, but we don’t actually remember them—we don’t know them.”

He set out to change that, researching the soldiers on honour rolls in Ottawa Valley churches, then introducing congregations to their stories. In 2014, he began research for the information centre at the Holten Canadian War Cemetery, and later began researching and editing for the Faces to Graves project.

Contacting families is a particularly rewarding aspect of the work.

The Kippen family sent four members off to serve during the Second World War. Harold and Meredith served in the army and Ivan in the navy. Ray joined the army in 1940. He wrote letters home about saving up to buy a store after the war.

He was in the second wave of Canadians to hit Juno Beach on D-Day. He saw combat in France, Belgium, Holland and Germany, and was wounded in action twice in 1944. He survived all that only to be accidentally killed by a comrade on March 28, 1945, when his platoon stopped to clean their weapons in a cellar in Bienen, Germany.

His brother Harold, who served with the Royal Canadian Engineers, placed poppies on Ray’s temporary grave in June 1945, a moment captured in a photograph on the Faces to Graves website.

“He was doing a fine job and was very well liked by the remainder of the boys. We all feel his passing keenly,” wrote his commanding officer Lieutenant Max A. Zink, in a letter to Kippen’s mother Mabel, shared by the Kippen family for Johnson’s profile about Ray on the Faces to Graves website.

“We are so, so appreciative. He brought to light a lot of things we had no idea about,” said Elaine Graham, Kippen’s niece, who lives in Ottawa. Like many families, the Kippens did not discuss the war, so the following generation knew little about Ray, although his name is inscribed on the cenotaphs in Arnprior and Calabogie, communities close to the Kippen family homestead.

There’s a sense of urgency now about collecting the stories of Second World War dead. Most of their comrades who survived have also died, as has the generation of families who knew them well.

Holten Canadian War Cemetery has collected photos and biographies for about 1,000 soldiers.

“Some are a few paragraphs, others are dozens of pages,” said Henk Vincent of the Holten information centre, where the biographies are available on computers. About 80 per cent of them are also available on the Faces to Graves digital monument.

“But we are still looking for personal photos of 420 soldiers who are buried in Holten.”

Holten is the burial place of 1,355 Canadian soldiers who died at the end of the war in eastern and northern Netherlands and in Germany. The Battle of the Scheldt accounts for most of the 986 Canadians in the Bergen-op-Zoom Canadian War Cemetery. Groesbeek has 2,338 Canadian graves and the names of nearly 100 Canadians with no known grave inscribed on the Memorial Wall.

But Canadians are also buried in small cemeteries scattered throughout the Netherlands.

Many of them, said Valkenburg, are Royal Canadian Air Force crew who died in crashes and were buried in local cemeteries.

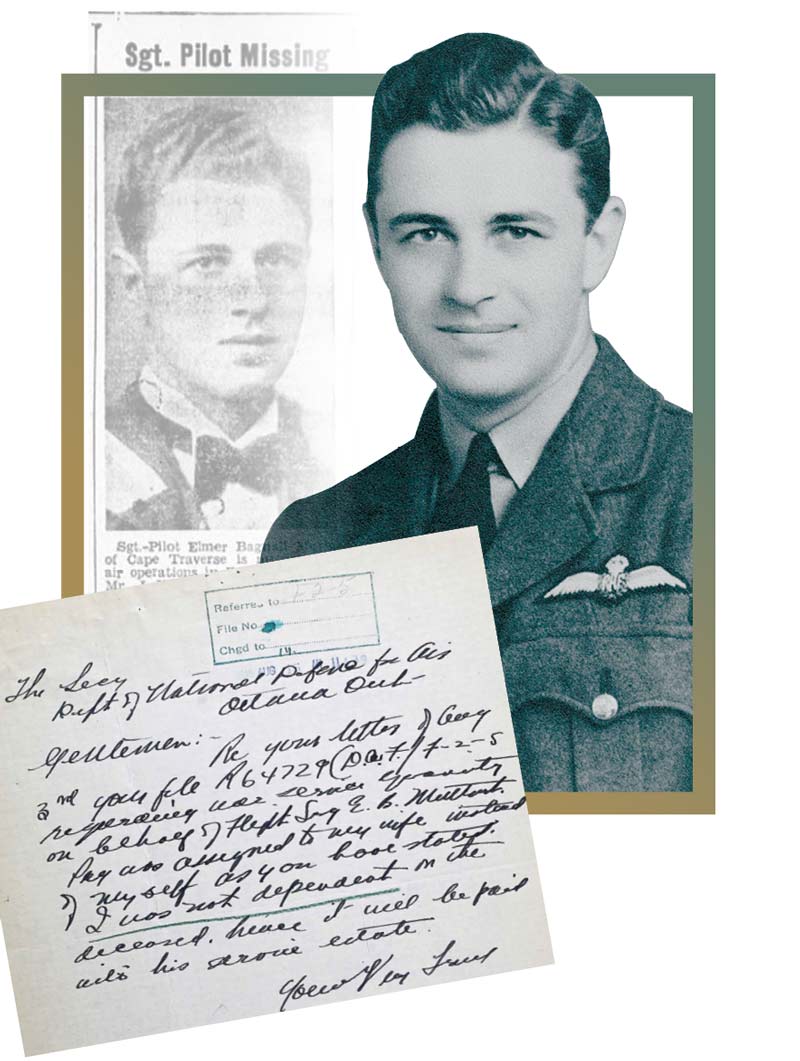

With a dozen missions under his belt, Muttart, 23, of Cape Traverse, P.E.I., was transferred to pilot the new Halifax heavy bomber L9561, joining 98 other bombers headed for Bremen, a German industrial city, on Oct. 12. 1941.

The bomber was intercepted over Friesland by a German night flyer. With one engine on fire, Muttart ordered the seven other crew to bail out. They survived and were captured by the Germans.

“Elmer was at the controls when the last chap went through the hatch.… He was a gallant captain and he died that we might live,” said co-pilot Norman Trayler. Those words form the title of a YouTube video honouring Halifax L9561 produced by Valkenburg and his wife Daria.

“The machine must have been well on fire by this time,” said Trayler, quoted in the video by Alexander Tuinhout, secretary of the Missing Airmen Memorial Foundation. “It was only his efforts that kept the disabled machine from crashing with all of us inside.”

People in the village of Wons said the aircraft was headed straight for the village but began sliding and zigzagging as Muttart aimed for a field outside the village. A wing fell off, and the Halifax crashed. Muttart is buried in the Harlingen General Cemetery.

In 2019, the Valkenburgs attended the unveiling of a plaque describing the fate of Halifax L9561 and its crew in the farmer’s field where it crashed.

Muttart was not listed on the Dutch digital monument at the time of writing. The Canadian Virtual War Memorial, a permanent tribute to the 118,000 Canadians and Newfoundlanders who died in service, has a few photos of the young airman, newspaper clippings reporting his death, pictures of his gravestone and his name on memorials. But no story about him sacrificing his life to save seven crew members and the village of Wons.

“Canadians can’t find their own stories in Canada,” said Johnson. Or at least, not easily. “We shouldn’t have to travel to Holten to see the biographies on the information centre computers. We shouldnʼt have to go through a website maintained in the Netherlands.

“What we should be doing is creating our own website with all these biographies.”

—

Links to soldiers’ stories

Captain Thomas Emmet Clarke on the Canadian Virtual War Memorial

Faces to Graves digital monument

Flight Sergeant Elmer Bagnall Muttart on the Canadian Virtual War Memorial

He Died That We Might Live…The Story of Halifax L9561

On The War Memorial Trail Research Project

Advertisement