Canadian Wrens arrive in Britain in October 1944. [Royal Canadian Navy]

The ranks master seaman, leading seaman, able seaman and ordinary seaman will be scrapped and likely replaced by equivalent ‘hands’ or ‘rates,’ depending on the outcome of discussions and an informal survey launched by the navy.

Lieutenant (Navy) Jamie Bresolin, a Department of National Defence spokesman, told True North Magazine that naval leadership decided to change the ranks to reflect the more progressive character of the force.

“The RCN, one of Canada’s top employers in 2019 according to Forbes, prides itself on inculcating an inclusive, diverse, gender-neutral and safe workplace,” said Bresolin. “Therefore, it was recently determined by naval leadership that an organization that has long since had gender-neutral terms for its personnel—sailor or shipmate—needs to reconsider some few rank titles that are rich in history, but perhaps not reflective of the modern, progressive service that is the RCN today.”

DND and the Canadian Armed Forces were listed 115th on the Forbes 500 list of top Canadian employers, just behind Home Hardware and ahead of Blue Cross. Google topped the list.

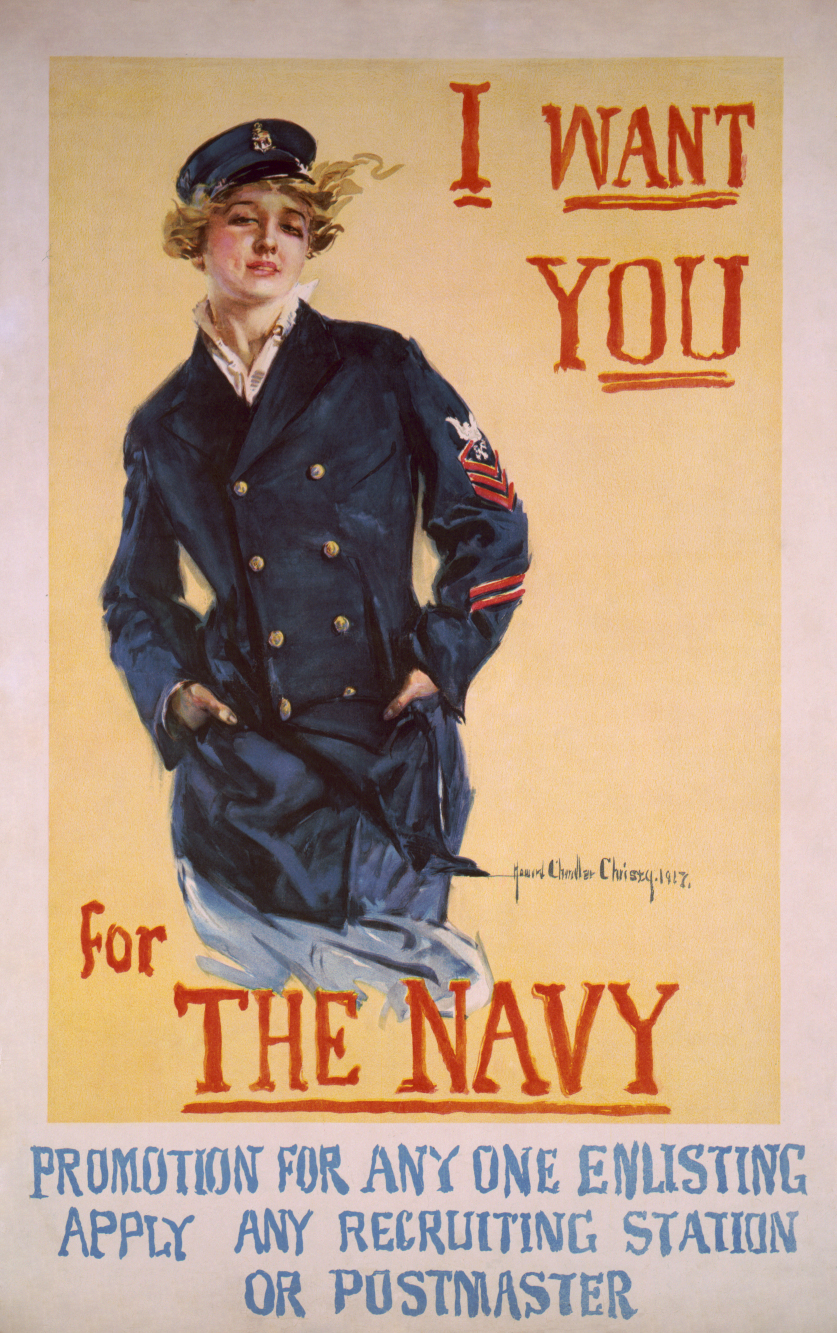

An American First World War recruiting poster featured model Bernice Tongate, who enlisted in the U.S. Navy the very day that illustrator Howard Chandler Christy sketched her. [U.S. Library of Congress]

“It’s good to get all those resources, all this new technology and new ships,” Canadian Coast Guard Commissioner Mario Pelletier said in a recent interview. “But without people, I’m not going to be able to operate or to support or to manage the operations. So I need people.”

The coast guard says up to 15 per cent of its positions are currently vacant, representing a shortfall of roughly 1,000 people.

Vice-Admiral Art McDonald, RCN commander, has said the navy is short by about 850 sailors. The deficit is manageable under current peacetime conditions, McDonald said, but there is concern over what would happen should operations need to be dramatically ramped up.

Common seamen of various grades of skill and experience made up the vast majority of a man o’ war’s crew in the British navy of the 18th and early 19th centuries, and they were organized as deemed necessary by the ship’s chain of command.

They were the grunts of the seagoing complement, doing the lion’s share of the heavy lifting aboard ship.

“It’s part of the journey,” explained one veteran navy man. “As one moves from Ordinary to Able to Leading and finally Master Seaman, the nature and degree of physical work diminishes a little. By the time they make Petty Officer, they are in leadership roles and instruct how by orders versus demonstrating by example.”

Their roles—including engineers, weapons technicians and maintainers—have evolved too.

“They aren’t climbing masts and yard arms, but they do climb boarding ladders, staircases and haul ropes on a regular basis. Replenishment at sea is intensely physical, as are boarding operations.”

A member of the Women’s Royal Canadian Naval Service was depicted on the cover of The Star Weekly on Sept. 12, 1942. [Toronto Star]

“If a person doesn’t join the navy because of the word ‘seaman,’ the navy doesn’t need them and you wouldn’t want that person holding a hose in your firefighting team,” wrote Harry Skinters.

Navy veteran Tim Beazley said the military “is supposed to be an organization that shows strength and unity among members, not something that society finds politically correct.”

Added retired master seaman Harkiran Kaur: “If they think changing the names of the ranks will improve recruitment, they are insane. Maybe fix the rampant harassment first.”

Roughly equivalent to the army ranks of private through master corporal, the use of ‘seaman’ is far from unique to the Canadian navy, though some services have scrapped the term—notably the Royal Navy, on which many of the world’s seagoing forces are based.

In the RN, which used to top up its ships’ companies via press gangs, ranks below petty officer begin at able rate (2), followed by able rate and leading hand. The U.S. Navy, on the other hand, has seaman recruit, seaman apprentice and seaman.

Artist Albert Alexander Smith depicted a post-revolution Russian sailor of the early-20th century. The Soviet navy used the rank Red Fleet man (krasnoflotets) until 1943, when it restored the rank of seaman. [Albert Alexander Smith]

The most junior rank in Imperial Russia was seaman 2nd class (matros vtoroi stati). The 1917 Revolution led to the term Red Fleet man (krasnoflotets) until 1943, when the Soviet Navy reintroduced the term seaman along with badges of rank.

The Russian federation inherited the term in 1991, as did numerous other former Soviet republics.

Frank Boam, a seaman aboard USS Mississippi, pictured in 1910. [US Militaria Forum]

Matelot has long been a slang term for sailors in the British and Canadian navies. ‘Seafarer’ has been an increasingly used term among civilian sailors—or seamen, as The Canadian Press long insisted civilian sea-goers be called, reserving ‘sailor’ for navy crew.

The chief of the defence staff, General Jonathan Vance, has made gender issues a central element of his tenure. Under Operation Honour, he calls for women to comprise 25 per cent of military ranks by 2026, up from the current 15.9.

But some of the thinking going into the effort suggests not enough has changed.

Joy Bright Hancock, a Yeoman (F) in the U.S. Navy Reserve in 1918. The Americans and British first recruited women during the First World War. [U.S. Navy/U.S. Library of Congress/WA-WW-3-13993]

Besides being overwhelmingly male, Facebook reaction to the navy’s proposed changes in the junior ranks appeared to be largely from retired navy personnel, prompting Genevieve Annabelle Reynolds to write: “So many people acting like they had it so much tougher but are failing to adapt…the irony.”

Able Seaman Enio Girardo of HMCS Edmundston, a flower-class corvette that served on transatlantic convoy runs in WW II. Girardo was washed overboard and rescued by his shipmates during a storm at sea. [DND/LAC/PA-151545]

“If the RCN wants to be more attractive for potential recruits,” he wrote, “give them daycare, and assurance that families will have access to medical care on posting.

“And, certainly, if you want to assign folks to the West Coast with its huge cost of living, you need to address this. Fiddling around with names/gender of ranks…will not bring the desired effect.”

Canadian navy veteran Chris Martin described how small measures can reap big rewards in a service that is notorious for its stubborn grip on tradition.

“For generations, women in the service were marginalized, assaulted and harassed,” Martin wrote. “They felt unsafe to bring concerns up the chain for fear of being removed from the ship or dismissed and swept under the rug.

A First World War recruitment poster by American illustrator Howard Chandler Christy. [U.S. Library of Congress]

“Just because we’ve always done something a certain way,” he concluded, “doesn’t mean it was the right way; it may have just been the easiest.”

The Women’s Royal Canadian Naval Service was established in July 1942, much later than the British Women’s Royal Naval Service. More than 6,000 Wrens served in the Second World War in 22 specialized occupations, many previously considered exclusively male, and some in hazardous locales.

The Wrens were disbanded after the war ended, reconstituted during the Korean War, and disbanded again when the forces were merged in 1968.

Female recruitment expanded in the 1970s, but it wasn’t until a series of breakthroughs during the 1980s and 1990s that women were allowed to serve aboard Canadian navy ships, with the submarine service the last to allow them, in 2001.

Advertisement