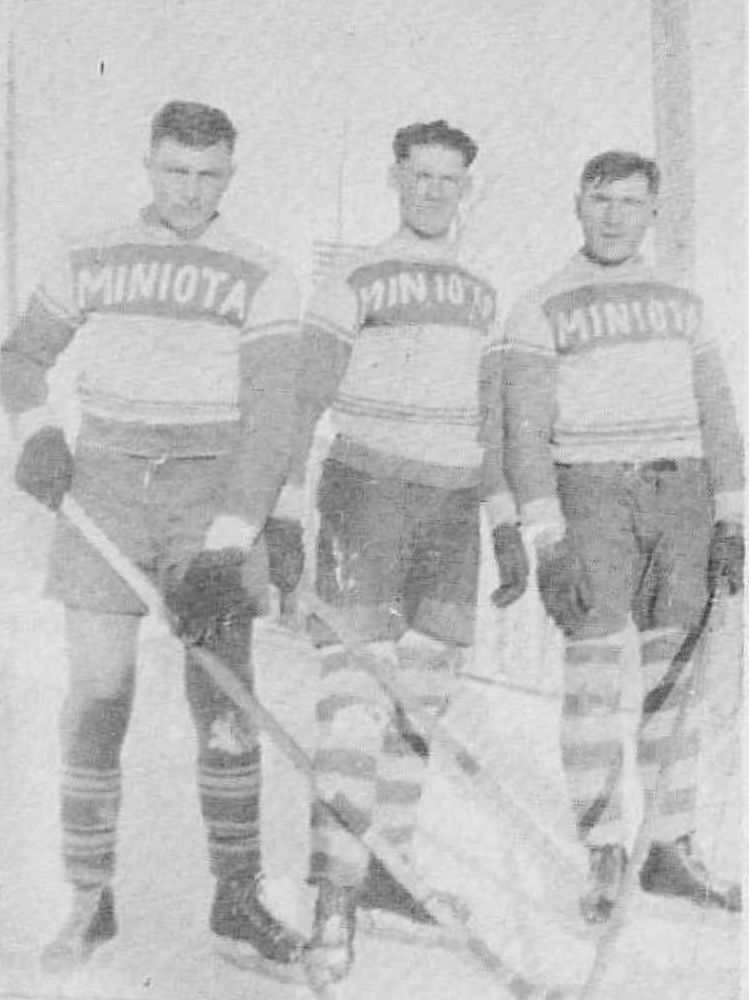

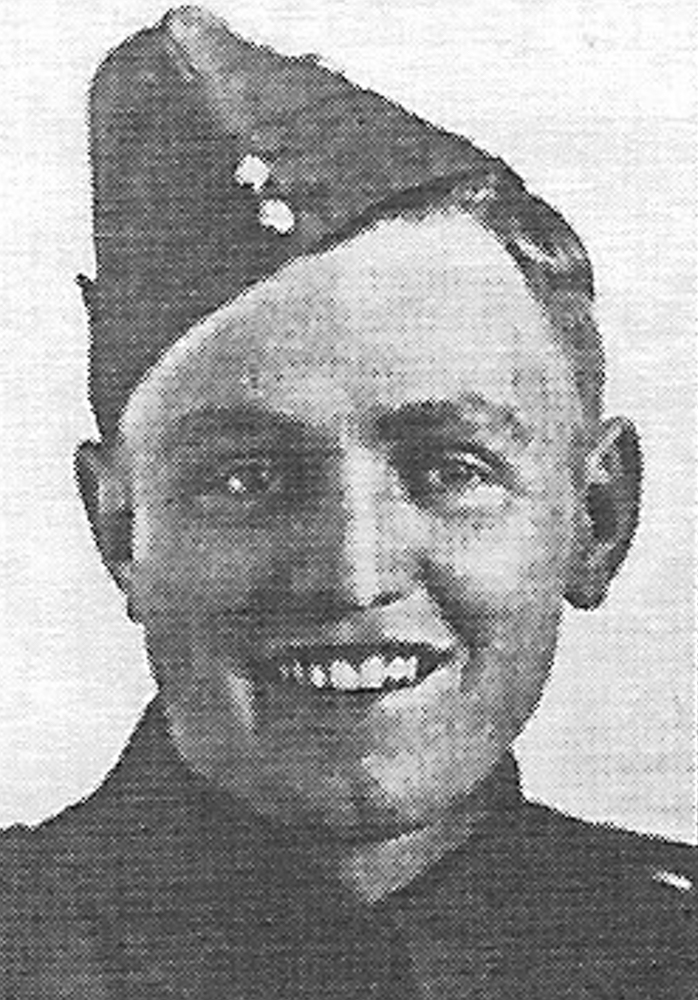

At the outset of the Second World War, Don MacPherson and his brother-in-law Wilf Barrett set off with two friends from Miniota, Man., intent on joining the air force.

But on their way, they passed a Winnipeg Grenadiers recruiting office and were persuaded to enlist.

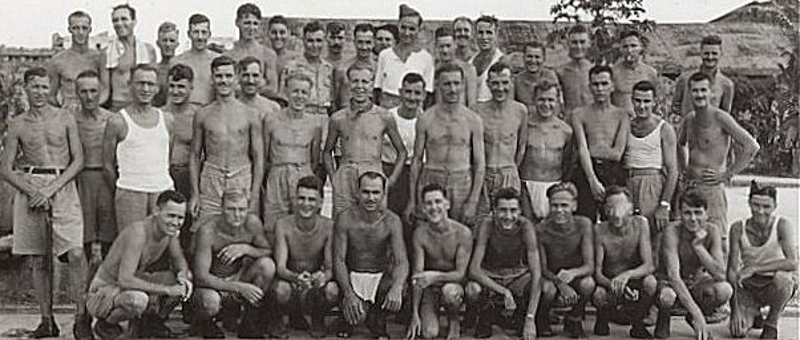

After training in Winnipeg, they were sent to Jamaica where their main duty was guarding German and political prisoners.

“We spent 16 months there enjoying life, but wishing we were in action,” recalled MacPherson.

In 1941, they got their wish, and were sent to Hong Kong. They arrived on Nov. 16 and settled into the Sham Shui Po barracks.

On Dec. 8, MacPherson saw a Japanese aircraft drop a bomb on the officers’ mess, as he recounted in a memoir on the Hong Kong Veterans Commemorative Association website. Soon, he and his ‘B’ Company comrades were in pillboxes on Mount Nicholson, fighting the invaders.

The Japanese had captured a police station on the mountain, and ‘B’ Company was ordered to retake it. They left at dusk and immediately ran into an enemy patrol.

“A bayonet fight ensued and several of our boys were killed,” he recalled.

One day some B-29 bombers flew over the camp, and soon it was a regular sight. “We could tell that the war had taken a turn.”

They would not be the last. The 17 days defending Hong Kong from Japanese attackers were bloody indeed.

On Dec. 24, MacPherson was in a trench with Barrett when it was hit by mortar fire. His brother-in-law was killed instantly by shrapnel.

“The island surrendered that Christmas day, 1941. My first reaction was relief as we were completely exhausted from lack of sleep,” wrote MacPherson.

Nothing was left but bare cement walls and floors. We were given one blanket and we had to sleep on the floor.

Captured Canadians were told not to destroy their weapons “but we smashed them over a railing anyway.” The Japanese would get no benefit from their equipment.

“The Chinese had gone in and stripped the huts, removing the floors, windows and frames and light fixtures,” recalled MacPherson. “Nothing was left but bare cement walls and floors. We were given one blanket and we had to sleep on the floor.”

They were also given a single spoon, and no bowl. So, MacPherson cleaned out a jam can he had found in a garbage heap. He would use that for the next two years until he was sent to a camp in Japan.

“We had very little each, mainly rice and not too much of that. It was dirty and had a lot of white worms in it. It was a hard life.” MacPherson’s weight dropped from 170 pounds to 103.

“The whole camp was actually starving to death. Many prisoners and civilians in Hong Kong did starve to death during the first year.”

Food was never far from mind.

“Hunger dominated our lives. Our stomachs were actually gnawing day and night for nearly four years.” And inevitably, vitamin deficiency diseases followed—beriberi, pellagra, dysentery, diarrhea and loss of eyesight.

“It didn’t matter how hard you tried not to talk about food—it always came up. We would get together and vow that we wouldn’t discuss food. Two minutes later we would be back on the subject. Everyone made up recipes and talked about the dinners their wives and mothers used to make.”In August 1943, MacPherson was among about 300 Canadian and British prisoners sent to camp Ōeyama, in Japan. “A real hell hole,” MacPherson called it.

“Half the camp worked in the coal mine and the rest of us worked at a surface nickel mine.” The fruit of their labour produced munitions that were used against the Allies.

The men worked seven days a week. “We would leave the camp before sunup…it would be dark when we got back to camp at night. If you got too sick or too weak to work then you were put on half rations and that would be the end of you.”

Even under these brutal conditions, the men managed some sabotage.

They routinely filled railcars with about half a ton of nickel ore, pushed it onto a main line, hooked it to some other cars and sent them downhill where they would be dumped.

“The cars had a long hand brake…(and) when we came to a curve, instead of braking, we would all jump off.” The cars and the track were wrecked.

The Japanese “would jump up and down and holler but never seemed to realize that we did it on purpose. We would spend days cleaning up the mess, but that was all part of it.” Stopping production for a few days was a way for the prisoners to continue contributing to the war effort.

Our stomachs were so shrivelled up—but we had all this food and no one to tell us not to eat too much.

The men were deliberately starved. Red Cross parcels regularly arrived, but rarely got to the prisoners. The aid was kept in a warehouse and often looted by their captors.

“They would start weeks ahead promising that if we would increase our loads per day for so many days, they would give us a parcel.” It turned out to be one parcel for four men. But that was not the only deception. Now their quota had been set at that higher output.

“We never fell for that again,” noted MacPherson.

And then it was over.“One day three American fighter planes came over, flew very low and dropped packages of canned coffee, cream and sugar wrapped in women’s underwear!” And three days later, 50-gallon (190 litre) drums of food were dropped.

“When they came it was a sight that no one in that camp could ever forget. All those parachutes coming down…some didn’t open and smashed the huts to bits.

“Our stomachs were so shrivelled up—but we had all this food and no one to tell us not to eat too much. I ate 32 of those large Hershey bars and 11 large cans of peaches in two days.” MacPherson suffered the consequences.

When he rejoined his family, who had moved to Winnipeg during the war, MacPherson found out he had been made a sergeant on Dec. 23, 1941.

“We sure had a party with the back pay,” he remembered.

“Little did I know that of the six men from the Miniota district who went to Hong Kong…that I would be the only one to return.”

Advertisement