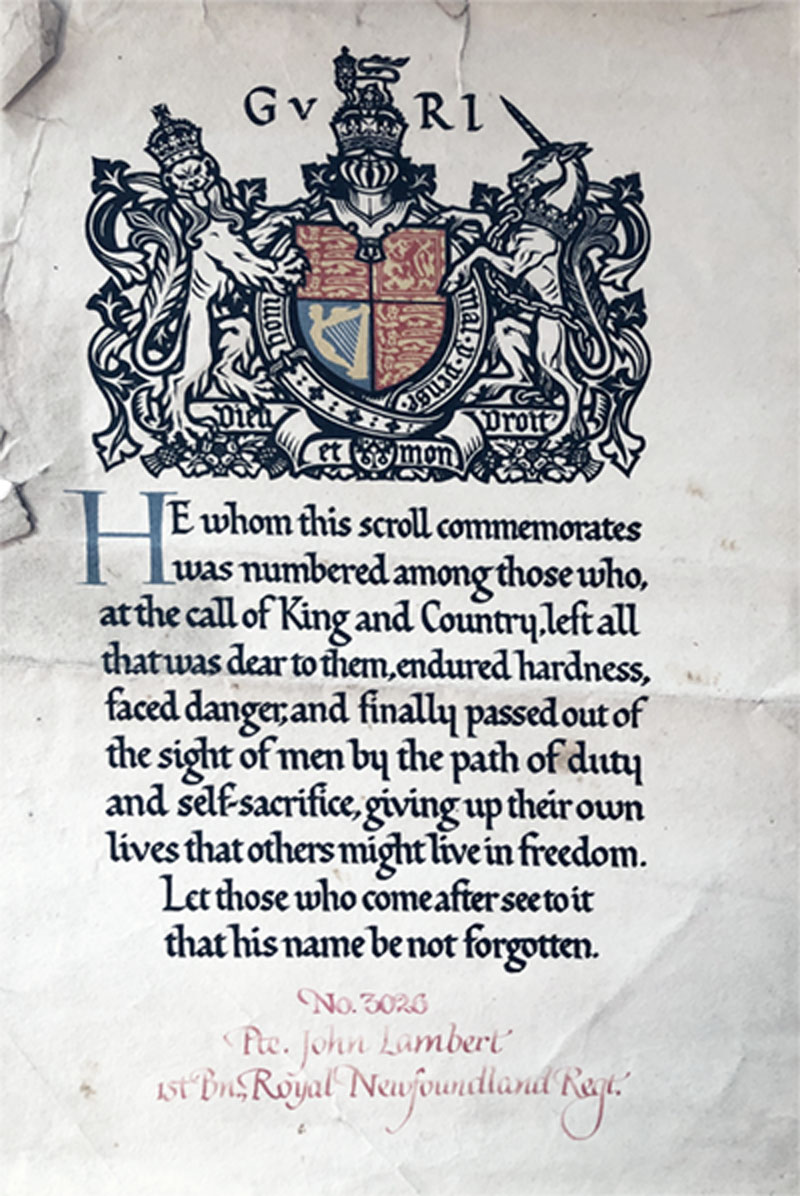

His name was John Lambert, and his remains lay undiscovered alongside those of a German and three British soldiers beneath Belgian soil near St. Julien for 99 years. He was the only one of the group identified.

“This has been a long and challenging investigation for us.”

The five were reburied along with two other soldiers of unknown origins during a military ceremony at the New Irish Farm Cemetery in West-Vlaanderen on June 30.

“This has been a long and challenging investigation for us,” said Louise Dorr, a caseworker at the British Defence Ministry’s Joint Casualty and Compassionate Centre. “It’s a matter of great sadness to me personally that we haven’t been able to identify any of the British soldiers or the German casualty.

Their remains were discovered during a planned archeological dig near a former field ambulance relay post that had been set up on a local farm during the Third Battle of Ypres, better known to Canadians as Passchendaele.

“This relay post was most likely located within 100 meters of the location where Private Lambert was recovered in 2016,” said a Defence Department statement.

“It is believed that he and the other soldiers found with him were buried near this relay post and for unknown reasons their remains were not found and recovered following the war.”

“It’s the first time anyone from the regiment has been identified like that.”

Walsh dug up census, parish and baptismal records; social media accounts; and local statistics, along with Ancestry.ca information and more to create genealogy reports, which he then forwarded to the forensic anthropologists in Ottawa.

In December 2020, he got an e-mail from casualty identification co-ordinator Sarah Lockyer confirming the remains belonged to Lambert.

“It’s the first time anyone from the regiment has been identified like that,” Walsh told CBC. “Very satisfying, as an archivist, to have used my training, my experience, the records, of course, and my understanding of the process to help.”

Lambert died a year before the regiment was awarded its “Royal” designation, the only combat unit to receive one during the 1914-18 war.

Born in St. John’s, Nfld., the former labourer was 16 years old when he joined up. He told recruiters he was 18.

Lambert was killed almost a year later—Aug. 16, 1917—at the Battle of Langemarck, an offensive during the Passchendaele campaign named for the village in West Flanders near where it took place.Lambert was among 103 KIAs from the Dominion of Newfoundland that day.

Lambert served with the regiment’s 1st Battalion, part of the 88th Brigade of the 29th Infantry Division of the British Expeditionary Force. Two unidentified soldiers found alongside him came from the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers and the Royal Hampshire Regiment. Both units suffered so many casualties on Aug. 16, 1917, that present-day British authorities couldn’t even attempt to identify them.

British offensives began northeast of Ypres on July 31, 1917. The 29th Infantry was to capture the Gheluvelt-Langemarck section of the German line. It planned to fight its way through the enemy position for 1,400 metres, between the Ypres-Staden Railway on its right and the French First Army on its left.

The 88th Brigade, including the Newfoundland Regiment, would lead on the right, with the 87th on the left. Advancing next to the railway was the Hampshire Regiment’s 2nd Battalion. Together, they were to capture the first two objectives.

Originally planned for Aug. 13, the attack was delayed twice by heavy rain and mud. The Steenbeek, a normally small watercourse, had overflowed its banks and flooded surrounding trenches and craters.

The Newfoundlanders’ ‘B’ and ‘C’ companies were in the first wave of attack at 4:45 a.m. on Aug. 16. ‘A’ and ‘D’ companies followed. Slogging through the mud, the Newfoundlanders still managed to keep up with the creeping artillery barrage that covered their advance.

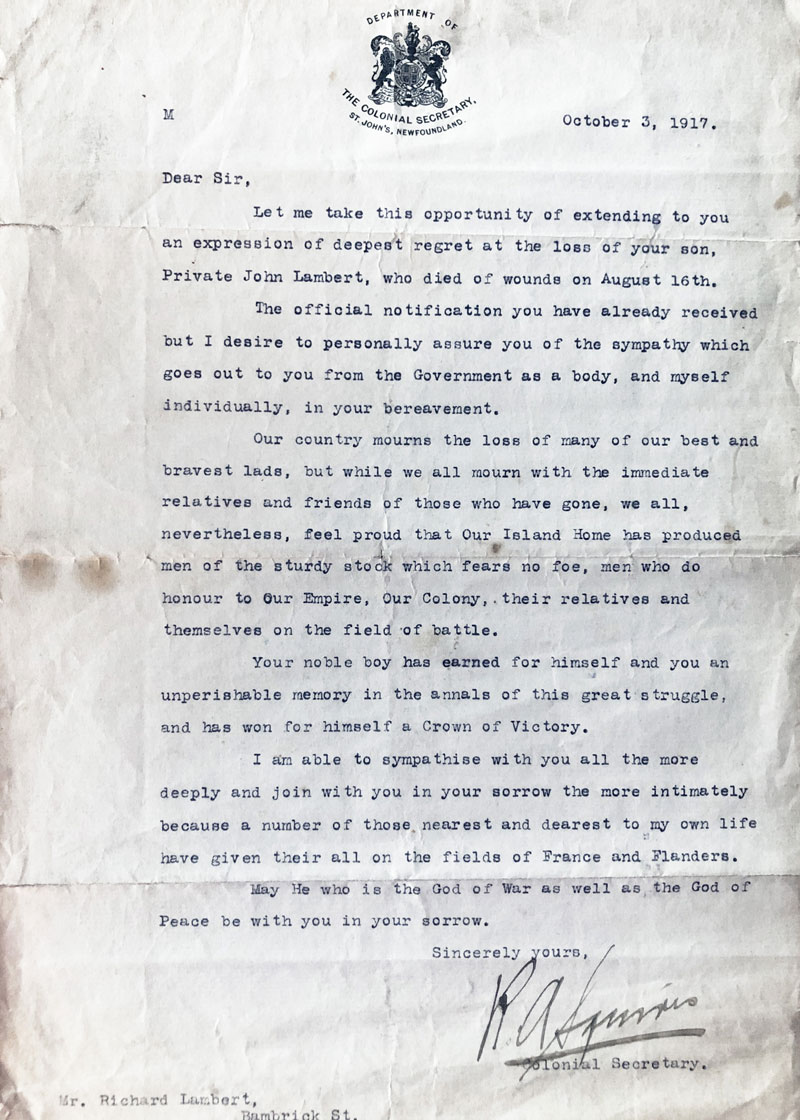

“Our country mourns the loss of many of our best and bravest lads,” colonial secretary R.S. Squires wrote Lambert’s father, Richard, on Oct. 3, 1917, in a one-page letter rich in post-Victorian rhetoric.

“But while we all mourn with the immediate relatives and friends of those who have gone, we all, nevertheless, feel proud that Our Island Home has produced men of the sturdy stock which fears no foe, men who do honour to Our Empire, Our Colony, their relatives and themselves on the field of battle.

“Your noble boy has earned for himself and you an unperishable memory in the annals of this great struggle and has won for himself a Crown of Victory.”

Victory above ground would take some time, however.

The overall campaign ended in November, when the Canadian Corps captured Passchendaele.

The offensives were plagued by heavy rains, compounded by poor drainage and lack of evaporation. The British and French forces were particularly affected since they occupied low-lying ground and attacked heavily bombed areas.

Mud and water-filled craters slowed infantry operations and poor visibility limited artillery observers and observation aircraft.

The lack of air support enabled German forces to reassemble on the battlefield unobserved and largely unhindered. Counterattacks quickly recaptured most of the lost territory.

Rain, along with German successes, exacted their tolls and forced the British to halt the offensive for three weeks into early September. When the sun finally emerged and the breeze picked up, drying much of the ground, the offensive resumed.

British combat engineers rebuilt roads and tracks to the front line. Artillery and fresh divisions were transferred from armies to the south, and tactics were revised. The main offensive effort was shifted southward until rain returned.

The overall campaign ended in November, when the Canadian Corps captured Passchendaele. Total casualties are wildly disputed—between 240,000 and almost 450,000 Allied; 217,000-400,000 German.

It would take two more campaigns—the Battle of the Lys (Fourth Battle of Ypres) and the Fifth Battle of Ypres in 1918—and 200,000 more casualties before the Allies reached the Belgian coast and the Dutch frontier.

“The soldiers taking part in today’s service can see they walk in the footsteps of the giants who went before them.”

Lambert’s name would be memorialized on one of three bronze tablets at the base of the Beaumont-Hamel Newfoundland Memorial that bear the names of more than 800 Newfoundlanders who died in the war and have no known grave. As with Canadians whose names appear on the Vimy Memorial and have since been identified, it will remain there.

Relatives and Canadian, British and Belgian government representatives attended the burial ceremony conducted by Canadian and British military chaplains. Members of the Royal Newfoundland Regiment carried Lambert’s remains to his final resting place among his Empire comrades-in-arms.“The soldiers taking part in today’s service can see they walk in the footsteps of the giants who went before them,” said Dorr.

The New Irish Farm Cemetery is one of more than 200 memorials and 23,000 burial sites in 153 countries maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. They encompass 1.7 million soldiers, sailors and air crew from the two world wars.

“Today these men have been buried at our cemetery alongside their comrades, with respect and dignity,” said the commission’s Liz Woodward.

“We are honoured to be able to formally recognize Pte. John Lambert and, although it has not been possible to identify the other casualties, we pay tribute to the ultimate sacrifice they have made. We will ensure the graves of these brave soldiers are cared for with dedication, in perpetuity.”

NAMING THE NAMELESSThe Canadian military’s Casualty Identification Program identifies the discovered remains of unknown Canadian service members so that they may be buried with their name, by their regiment and in the presence of their family.

The program also identifies those previously buried as unknown soldiers when there is “sufficient historical and archival evidence to confirm their identification.” They are then given a new headstone with their name, unit and a personal family inscription, if requested.

The program has identified 20 Canadian soldiers from the First World War and 19 from the Second.

Advertisement