The tears fell nearly as heavily as the rain when Denise Rousseau finally fulfilled the promise made years ago to her dying father Fernand.

It was the final day of the In Our Fathers’ Footsteps (IOFF) pilgrimage to the Netherlands and the last commemorative ceremony, this one at Bergen-op-Zoom Canadian War Cemetery.

There, by happenstance, she came across the grave of Regis Rousseau.

“He was my father’s cousin,” said Rousseau, of Laval, Que. “They joined together and trained together. Eventually they were split up. Dad heard about Regis passing and all his life we wanted to find him.”

In 1983, her father made his own pilgrimage and searched for Regis’s grave.

“He was sort of convinced Regis was buried in Groesbeek (Canadian War Cemetery).” But the grave was not there. “My father was hoping we would find his cousin, which we did not before he passed. I made a solemn promise to him that I would try to find him.”

She searched the graves again on the pilgrimage, first in Groesbeek and again in Holten, before she finally found Regis’s headstone in Bergen-op-Zoom.

“Totally by accident,” she said, tears flowing freely. “That’s why it’s so emotional on this last day to find him and to be able to keep my promise.”

Regis Rousseau was among more than 7,600 Canadians who lost their lives during the battles to end the brutal five-year Nazi occupation of the Netherlands. But some 150,000 Canadians and Newfoundlanders who served there returned home, including Lieutenant Gilbert Hunter, who had a fruitful career in Toronto before a long retirement in Ontario’s Muskoka region, where he died in 2009.

Like many Second World War veterans, Gilbert rarely talked to his family about his experiences. But on his 80th birthday, he gave his daughter Karen Hunter, of Guelph, Ont., a memoir of his service, sparking her interest in his military career.

“When they came home, they were too overwhelmed to process it, and they weren’t encouraged to talk about it,” said Hunter. “For many years they didn’t understand why we would want to know about it. You know, ‘it was in the past and nothing could be changed.’ And they wanted to resume their lives.”

Regis Rousseau was among more than 7,600 Canadians who lost their lives during the battles to end the brutal five-year Nazi occupation of the Netherlands.

Hunter wanted to go to the Netherlands to learn about her father’s experiences, to walk in his footsteps. She soon realized others shared a similar ambition and came up with the idea for the In Our Fathers’ Footsteps pilgrimage. Hunter had the help of many Dutch volunteers, particularly Peter van der Meij, of Uden, logistics co-

ordinator for the pilgrimage. He and his wife Ans hosted Hunter’s family on their earlier visits and a warm cross-Atlantic, multi-generational friendship blossomed.

Plans for the trip in 2020 were delayed by the pandemic, but 89 people signed on for the IOFF pilgrimage in September 2022. They walked more than 60 kilometres across the countryside, along trails and roads and through villages and towns. Along the way, they learned some history and participated in ceremonies at monuments, battlefields, gravesites and cemeteries. They joined in many joyful celebrations as well.

Among the pilgrims were brothers Jonathan Shiff of Jerusalem, and Elliott Shiff of Toronto, who were continuing their long search for the story of their great-uncle, Sergeant Harry Bockner, of Guelph, Ont.

Bockner went overseas in October 1942 and fought through the entire Italian campaign. He went to the Netherlands with the 1st Canadian Division in March 1945. He was killed April 11.

“All we knew of him were two pictures hanging on the wall,” said Elliott. In the 1990s, he came across boxes containing more than 1,000 letters his grandmother had received from Bockner, her youngest brother.

The Shiffs came to know their great-uncle through the letters. “They were entertaining at times, at times funny and other times disturbing,” said Elliott. But they were also quite profound. “Harry was a man who came to a much deeper understanding of his own life, under the most difficult circumstances imaginable.”

The brothers discovered that before the war, Bockner had been the life of the party, “sometimes ones to which he had not been invited.” He worked in the fur business before enlisting at the age of 31. They traced his service through England and Italy and wanted to know more about his experiences in the Netherlands.

In 2005, Elliott placed an advertisement in Legion Magazine’s “Lost Trails” section and received five messages, including three from soldiers who had fought with Bockner. One of them was Gilbert Hunter, who had trained with Bockner and served with him in Italy and the Netherlands.

Bockner had taken shelter in a barn during a German attack as Canadians crossed the IJssel River to establish a bridgehead near Zutphen. He was killed by shrapnel there. Hunter had helped load Bockner’s body onto a truck and had visited his grave twice.

When the Shiffs said they’d like to visit the spot, Hunter said, “I know exactly where you need to go.”

In April of 1945, when Bockner was under attack, schoolboy Johan Wolters was hunkered down with his mother and father in the basement of their farmhouse. Realizing their house and barn were targets, the family fled during a break in the shelling. Now a great-grandfather, Wolters recalls seeing Bockner’s body being loaded into the back of a truck as his family ran to a nearby wood.

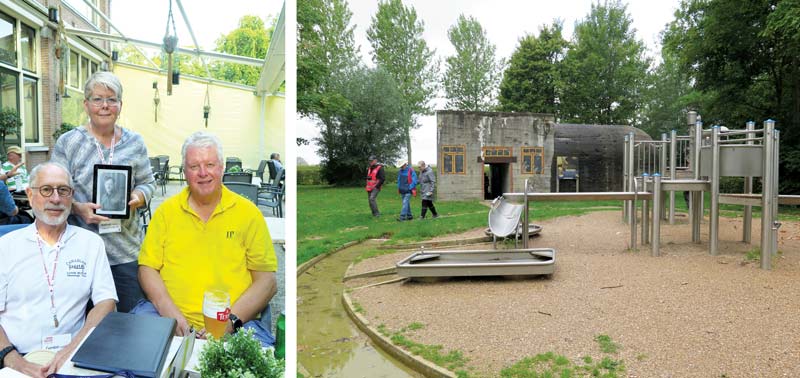

The Shiff brothers received a warm welcome from the Wolters family when they first visited in 2007, and again during the 2022 IOFF pilgrimage.

Bockner is buried in Holten Canadian War Cemetery, but the brothers knew he had been reinterred. Where was he originally buried?

Word was put out in the community of Dutch people who support remembrance of Canadians and eventually it reached the ear of Antje van Gietenbeek, explained van der Meij. “She said, ‘I know the spot.’”

After the war, she lived in the house next to the field where

temporary graves were dug for 11 Canadians. Every day on her way to school, she would put flowers on the graves, including Bockner’s.

Van der Meij organized a ceremony in that same field during the pilgrimage. Van Gietenbeek’s grandchildren placed flowers on markers representing the Canadian graves and the Shiff brothers shared Bockner’s story and said prayers in Yiddish.

“My uncle Harry always wanted to travel after the war,” and visit the land that became Israel in 1948, said Jonathan. The brothers visited Bockner’s grave at Holten again during the 2022 pilgrimage, where Jonathan spread some dirt and stones he had brought from Jerusalem. Elliott and his wife Risa did likewise with earth and stones from Canada.

Also, at the Holten cemetery, pilgrim Kathryn Jordan, of Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ont., spread some of her father’s ashes. Her dad, John Jordan, served in the Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders (the Glens) and, after the war, “became quite a historian,” said Kathryn.

Although John spoke about his experiences with his family and regularly participated in annual remembrance ceremonies in his local community, he wanted no fuss made over himself.

“He was a shy man and very humble,” said Kathryn. “He always said the heroes were the boys that were left behind. I had a chance to stand at the grave of a boy who was left behind,” a member of her father’s regiment. “It was a special place to spread the ashes to honour those boys and my father.”

Van Gietenbeek’s grandchildren placed flowers on markers representing the Canadian graves.

Harm Kuijper, a member of the Warnsveld Memorial Committee and of The Liberation of the Netherlands Branch of The Royal Canadian Legion, has developed a website (ww2memorial.nl) that co-ordinates names of the fallen with topographical maps of regimental movement overlaid on a current map. Kuijper’s interest in war history expanded in 2005 to include Canadians when Zutphen named some streets in honour of Canadian liberators.

“I was able to determine where regiments were located and, in some cases, where a soldier was killed,” he said. “Everything came together like one big puzzle.”

The path of the Glens regiment is documented on the website, so he was able to guide Kathryn and her partner Gordon Loomes to many of the places her father knew.

Remembrance is part of the fabric of the Dutch people, Kuijper said, and care is taken to pass it on to the next generation. Liberation of the whole country is celebrated on May 5, but each village marks its own liberation day, and many have services on dates important to Canadians.

“Monuments are adopted by schools and families adopt graves of soldiers,” he said. “You can be invited to give a (school) lesson—it’s common.”

The war is such a part of Dutch culture that near Groede, a family amusement park incorporates German bunkers that had been camouflaged as houses, with curtained windows painted on the concrete exteriors. Children climb around on the play structures near the bunkers. But play can be interspersed with a history lesson as families tour the bunkers and read the poster boards describing wartime activity.

In the smallest villages, on the loneliest roads, pilgrims came across people who had stories of their liberation to share.

Marius Bakker’s family survived the war by cooking tulip bulbs. He still digs up bullets, bombs and grenades in his garden in the village of Woensdrecht, where he serves on council.

Riek Albert de la Bruheze was a child in Zutphen during the war and remembers the noise, the fear and staying in a bomb shelter. She came out to a park in Doetinchem to watch the Canadian pilgrims arrive, she said through an interpreter.

“They know what happened here,” she said, pointing to the welcoming people who lined the streets with Canadian place names.

The Fort Garry Horse stayed on in the city after the war, helping to build houses using materials recycled from buildings destroyed during the bombing and intense fighting. They also left a Sherman tank as a memorial in Canadapark. The neighbourhood is named after the regiment.

Nel Erlee came to a ceremony along a narrow lane near Vorden and shared her story of Canadians giving her a much-needed lift. As German blockades caused food supplies to dwindle in the west of Holland, her father sent her to a farm in the east, where there was more food. She was 16 when the area was liberated by Canadians.

“They enjoyed the fresh vegetables I gave them,” and in exchange, or maybe just kindness, repaired her shoes. Erlee told them she was desperate to rejoin her family in the west, who had just come through the Hunger Winter.

“Important this is,” she said, speaking English slowly. “They brought me all the way back home. In a jeep. From the east to the west.”

Geert Polak, who hid in a basement as a boy with his family during bombing raids and battles, has tended some graves in Bergen-op-Zoom Canadian War Cemetery for 50 years. Now in his mid 80s, he ensures flowers are placed on those graves every year on the anniversary of the soldiers’ deaths and on Canadian Remembrance Day.

These and many other stories were soaked up by pilgrims. Most came to the Netherlands simply to learn more about the area where their father or uncle or grandfather had served.

Linda Webb of Saint John, N.B., brought along the diary her father, Major Paul Maurice (Frenchy) Blanchet, wrote in the Netherlands in 1945.

“I had already followed his footsteps in Italy in 2013 on the 70th anniversary of the landing in Sicily,” she said. Webb was able to visit many of the places mentioned in his diary during the pilgrimage, and even stayed in a hotel in Ehzerwold that had been converted from a military hospital where her father may have been treated for dysentery.

Veterans Brad Hrycyna and Greg Mulatz of Regina wanted to expand their knowledge of Canadian war history, adding to what they had learned in half a dozen tours of battle sites in Italy, France and Belgium.

Veteran Brian Budden of Mississauga Ont., who had served with the Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada, wanted to learn more about where his grandfather served in addition to paying respects at graves of men from his regiment.

The IOFF pilgrimage began in Canada on Sept. 5, when the Canadian Remembrance Torch, commissioned by Hunter, was lit from the Centennial Flame on Parliament Hill. The torch was designed by engineering students Yuvraj Sandhu, Sebastian Tattersall and Anna Esposito of Hamilton’s McMaster University. Each carried the torch in turns throughout the trip.

The torch was passed on in a ceremony at Het Loo Palace in Apeldoorn to Princess Margriet of the Netherlands, for use in Dutch commemoration. The flame, contained in a special case for the flight over the Atlantic, was used to light the torch that led the marchers and played a central role in remembrance ceremonies.

For the pilgrims, remembrance also took the form of getting a sense of what it might have been like for the Canadians who fought in Holland at the end of the Second World War. Then, troops encountered frequent rain, snow and mud, and subsequently, were often wet and cold. The pilgrims got a similar experience in spades on their first 20-kilometre march, which began in Megchelen in the pouring rain.

On the bright side, no one was shooting at them.

The pilgrims walked more than 60 kilometres in total during the trip, through towns and villages, across country fields and along lonely roads, following routes Canadian troops travelled during the liberation of the Netherlands. Volunteer guides shared wartime history along the way.

They stopped at many memorials dedicated to Canadians, old and new. In May 2022, a monument was unveiled commemorating 500 people, including Canadian troops and aircrew, who died near Genkoppen en Wisch during the war. Meanwhile, in the village of Warnsveld, population 8,390, pilgrims visited a small cemetery where five Canadians are buried. The village donated a maple tree at the cemetery and dedicated a plaque to honour Canadians. Each grave had flowers the day of the visit.

The pilgrims also soaked up history at exhibitions both large, such as the Canadian wing at the Bevrijdingsmuseum (Liberation Museum) Zeeland in Nieuwdorp, and small, like the collection Christian Harkink transports in the back of his van to events he knows Canadians will attend.

“I learned more about the adventures my dad went through,” said Joanne Edey-Nicoll of Langley, B.C., of her father Alexander Edey. “When he was alive, he didn’t talk about it.”

Edey-Nicoll knew her dad had been wounded in 1945 and may also have been treated in the Ehzerwold hospital. She had been told how much the Dutch people appreciated what the Canadians did. “But nothing prepared me for the welcome we got,” she said.

Canadian flags were hanging everywhere: from flagpoles in people’s front yards, in shop windows and even on the sails of windmills.

On May 4, Dutch people remember the war dead and place flowers on the graves of Canadian and other allies. They party to celebrate their freedom the following day.

Pilgrims got their first taste of that as they marched in formation behind the City of Apeldoorn Pipes and Drums into Etten. Excited people crowded the sidewalks. Canadian flags were hanging everywhere: in people’s front yards, in shop windows and even on the sails of windmills. Four choirs put on performances.

Similar greetings (minus the choirs) were repeated everywhere the pilgrims stopped.

“I was overwhelmed at the reception,” said Jordan. “The streets were crowded with people laughing and clapping. These people have no idea who we are, whether my dad died or came home, what in fact any connection I had. Yet, we were Canadians, and they were happy to see us.”

Canadians who thought the long marches might wear off some pounds had those hopes dashed, for whenever they stopped marching, locals gave them delicacies—savoury bitterballen, orange liqueur, wine and cheese and pastries. Lots of pastries.

That warm welcome should reassure Canadians who worry that because the link to Second World War veterans is fast disappearing, the relationship with the Dutch people will, too.

The Dutch once thanked Second World War veterans in person. Now they thank the children of those veterans—really any Canadian—for the service and sacrifice of the men and women during the Second World War.

Will the friendship between the Netherlands and Canada ever fade? “Not if I have anything to do with it,” said Kuijper.

Advertisement