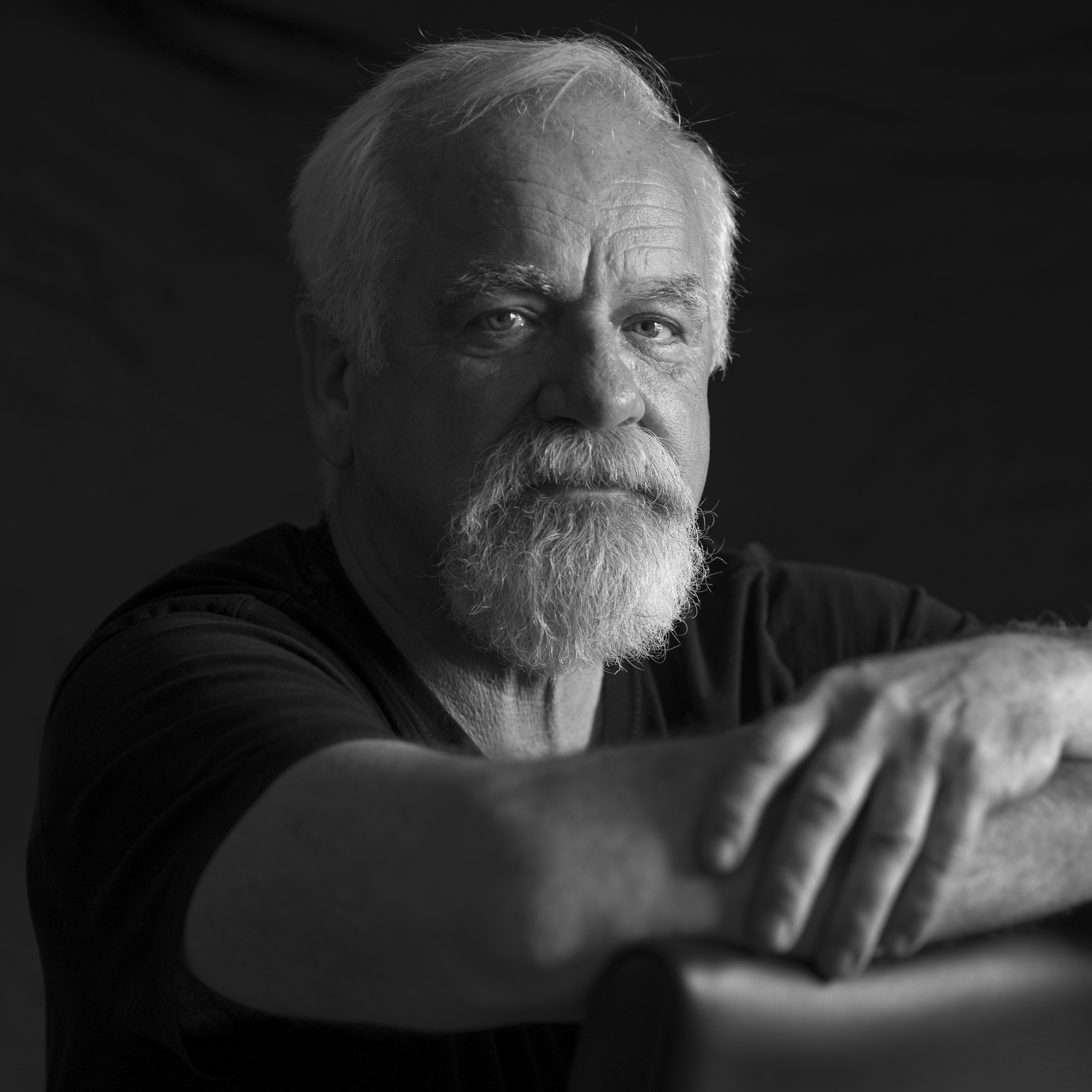

Jim MacEacheran led the team investigating battlefield fatalities in Afghanistan. They often had to reassemble the remains of individuals blown apart.

Story and photography by Stephen J. Thorne

Jim MacEacheran got a cool reception when he arrived in Afghanistan in 2002. It was not necessarily unexpected but his circumstances certainly were unique.

As a captain in the Canadian Forces National Investigation Service, he and his team were responsible for probing any allegations of wrongdoing, as well as every Canadian death, combat or otherwise, in-theatre. Canada is the only nation that does so.

They also performed the duties of a mortuary affairs team, collecting remains of soldiers killed in action and otherwise, identifying them, preparing them and shipping them back to CFB Trenton along with their report for final evaluation by a coroner in Toronto, the last stop on the Highway of Heroes.

“Did you bring your own food?” he was asked on arriving in Kandahar, where rations at the time were shipped in trays from the United States and steamed into something resembling meals, and small ones at that.

He was responsible for ensuring troops followed the rules of engagement. His arm’s-length reputation was cemented by a dogged months’-long investigation of Canadian snipers, who had emerged heroes from a 29-day operation with U.S. forces only to face questions over their alleged treatment of enemy dead.

No charges were ever laid and several of the snipers were awarded Bronze Stars for their actions in what turned out to be one of the biggest and most protracted battles of the war. Some two dozen Americans and up to 800 enemy died in the operation, during which two Canadian snipers set two distance records in less than a week. The second, 2,443 metres by Corporal Rob Furlong, stood for five years.

That was the investigation group’s first inquiry in-theatre, and partly because of that and partly due to the nature of their work in general, MacEacheran and his small teams of two or three were forever outsiders to the brotherhood of the combat arms, treated by the rank and file with varying degrees of disdain, mistrust and suspicion.

The necessary distance MacEacheran and his teams had to maintain to do their job, both from a perspective of independence and their own mental health—not getting too close in order to protect their psyches—alienated them even more.

Continued from MHM e-report No. 18

To MacEacheran and his investigators, it was the doctors, coroners, padres and social workers who were their colleagues and friends, along with the senior ranks of the combat arms through whom they sought support and co-operation. “I was not the most popular person at the daily O (Operations) Groups.”

They even kept their distance from regular military police and made a point of not attending the send-offs the fighting troops would hold for the dead, known as ramp ceremonies.

“I would not let my guys go to the ramp ceremonies,” MacEacheran says, explaining that “when you’re in Canada and you investigate a death, you interact with the family a little bit. But when you’re in-theatre, the family’s always there because that’s the unit and all the other soldiers and you see them all the time.

“You just don’t need that extra emotional baggage. You’ve already done your time with the body; you’ve had other members of your unit in there and given them their quiet time with the remains before you finish processing, and those were emotionally charged moments too.

“Some of these were kids, younger than my three sons.”

His first major post-mortem was the April 2002 friendly-fire incident in which an overzealous American pilot dropped a bomb on a nighttime live-fire exercise at the Tarnak Farms training ground southwest of Kandahar, killing four Canadian soldiers and wounding eight.

There were just two Canadian investigators then. It was MacEacheran who found the jawbone of one of the dead and brought it to the dental officer, who matched it to X-rays transmitted from home. He was helped by a U.S. military pathologist and mortuary affairs team who had just finished investigating the deaths of four American engineers killed by a booby trap.

MacEacheran joined the army at 17 and did tours in Cyprus, Beirut and Germany. He signed up with the National Investigation Service in 2000 and returned to Afghanistan in 2006 before retiring after more than 35 years in the service. He redeployed in 2010 as a reservist and walked away from the military life a major in 2014.

Before he did that, however, there would be many more investigations, each with its own set of circumstances and challenges, both physical and psychological. He even investigated a handful of civilian deaths, his reports forming the basis of compensation payments to Afghan families.

“I never saw any wrongdoing in all the ones we did,” he says.

His investigations of Canadian deaths form an independent and permanent record of their circumstances, references in case questions are ever raised and in many cases a foundation for lessons learned and subsequent changes in policy and practice.

The latter wasn’t always the case. “Sometimes,” he says, “shit just happens.”

As the mortuary affairs team, they as often had to reassemble the remains of individuals blown apart by the homemade bombs planted by the Taliban in and alongside roadways and pathways all over the Canadian zone of operations.

The camp clerk came to dread their visits, when they would ask for the passports of the dead. He would know why they were there before they even uttered a word. “I hate seeing you,” he would tell them.

Over time, their role became better understood and accepted. It was an education for everyone, even the coroner in Toronto, who couldn’t figure out why there were more teeth than bodies warranted after the Tarnak Farms tragedy. MacEacheran finally told him that many enemy had died at the former al-Qaida compound before the Canadians ever got there and his investigators had collected everything they found.

MacEacheran left with a profound and enduring respect for the troops who had so often shunned him and his colleagues. During one short period, there had been two deaths and a serious wound, and in each case, it was the same corporal out front with a mine detector. (Many bombs were designed to be undetectable).

“We interviewed him each time because he was one of the principle witnesses. And he was always ready to go out there again the next day. You look at these guys and you go: ‘Wow, that’s a lot of courage, right there.’

“Eventually, he got wounded too.”

MacEacheran was also wounded, only he didn’t know it.

He returned to Canada after his last deployment a hurting man. His “post-tour high” initially kept him blissfully unaware of the anxieties and trauma that were welling inside of him. Even when he started to recognize things, he set them aside.

“You’d walk around and see things that reminded you of stuff, like the dung beetles at Tarnak Farms. If something like a bottle of barbecue sauce spilled on the ground, it would trigger me.”

Eventually, the anxiety started to spill over. He hated crowds, and other drivers frustrated him to no end.

“I couldn’t go to Costco. I’d get frustrated easily. When I’d see drivers and people in stores who were oblivious to what’s going on, that would set me off because I’d have a heightened sense of awareness and I’d see the lack of awareness in others.”

He had flashbacks and nightmares; he was on edge and short-tempered. Laura, his wife of 37 years, started feeling symptoms too. Both ended up in counselling and now pursue separate equine therapy programs.

Now 60 and living on a farm in Prince Edward Island, MacEacheran says age helped him confront his situation and seek counselling. He could care less about stigma, which he considers an issue for younger sufferers of post-traumatic stress.

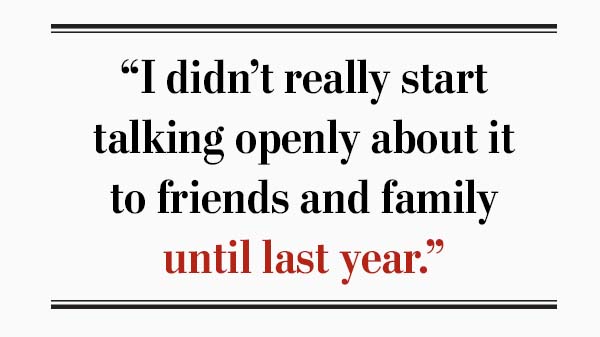

“When you finally accept it, you realize the damage you’re doing to the people around you and you come to terms with it. I didn’t really start talking openly about it to friends and family until last year.

“Then you find out others have the same issues, whether they’re volunteer firefighters or ex-Coast Guard. Some are going through the same struggles but they don’t have the screening or the support mechanisms that we do.

“Ourselves and the Mounties are pretty fortunate, really, being under Veterans Affairs. They’ve only gotten better dealing with it, whether because of public pressure or education or what.”

To view more images and read other instalments in Stephen J. Thorne’s Portrait of Inspiration project for Legion Magazine, please click below.

Advertisement