It had to be the worst of all bad ideas.

Saturday, March 7, 1807. HMS Halifax, a Royal Navy sloop, lies off Hampton Roads, Va. The Napoleonic Wars are in full swing, and the British are in Chesapeake Bay, blockading two French warships that had made port seeking refuge and repair after a storm.

About 6 p.m., First Lieutenant Thomas Warren Carter orders Midshipman Robert Turner and five crew into a jolly boat (a small dory) to weigh anchor.

Out of this simple task grows one of the contributing incidents to the War of 1812.

At least four, maybe five, of the six jolly boat crew decide to desert. A manhunt is launched, an American naval vessel is fired on and badly damaged, her captain wounded and four of her crew killed.

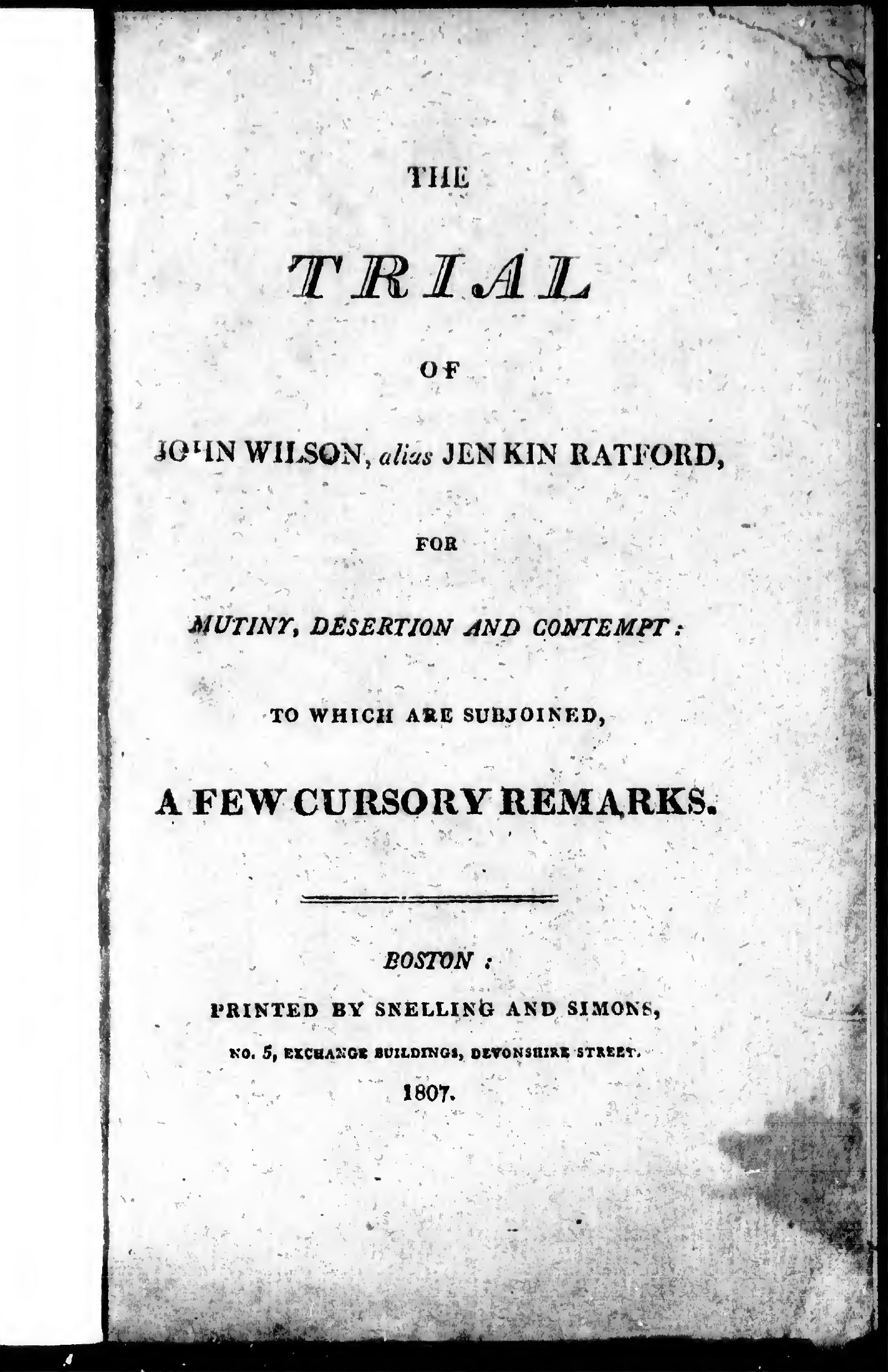

Later, back in Halifax, a court martial is convened mid-harbour, and one of those jolly boat crew is tried for mutiny, desertion and contempt. Then he is hanged from the ship’s yardarm for all to see.

Too bad for him.

Three others—yeoman of the fleets Henry Saunders, sail-maker Richard Hubert and captain of the main-top George North—were also British. Able Seaman William Hill was a 21-year-old Philadelphia native who enlisted at Antigua.

They had raised the anchor to the ship’s bows when a hard rain began to fall. Dusk was beginning to settle and a fog was moving in. Ignoring Midshipman Turner’s protests, they began rowing toward the nearest land, Sewell’s Point.

“The men took the boat from me,” Turner testified at Ratford’s trial, recorded in a contemporary account. “I hailed the ship repeatedly until silenced by Hill, who threatened if I hailed the ship any more he would knock my brains out and heave me overboard.”

An incredulous Carter ordered his red-coated Royal Marines to open fire. A volley of musketry and one cannon shot ensued, but the boat was already fading in the mist and failing light. The five deserters waded ashore unharmed, taking Turner with them. He managed to return to his ship a few days later, reporting that the others were making something of a spectacle of themselves in Norfolk.

“Saunders I think would have returned,” Turner said, “if he had not been threatened to have his brains knocked out.” By whom, specifically, Turner wasn’t sure. It seemed to be a matter of general agreement among the others, by his observation.

The deserters certainly did not lie low. An officer dispatched by Halifax’s captain, Lord James Townshend, saw Hubert and some of the others parading the streets “in triumph,” waving an American flag and recruiting for the USS Chesapeake.

Townshend’s attempts to recover his men were met with American inaction and passive obstruction—they gave him the runaround, in other words.

Townshend met with Saunders a few days later and when he asked him why he had left, the sailor told him he “did not intend anything of the kind, but was compelled by the rest to assist, and would embrace the first opportunity of returning.”

They started to leave together when Ratford approached and took Saunders forcefully by the arm, Townshend told the court martial, heard by an admiral and six captains aboard HMS Belleisle in Halifax Harbour on Aug. 26, 1807.

Townshend said Ratford was abusive and told him he would be damned if he would return to the ship. “With a contemptuous gesture, [he] told me he was in the Land of Liberty,” before the sailor dragged Saunders away.

“Finding that my expostulating any longer would not only be useless in obtaining the deserters but, in all probability, have collected a mob of Americans, who, no doubt, would have proceeded to steps of violence, I instantly repaired” to the British Consul’s house, Townshend said.

Word filtered down that at least some of the deserters—there were others, from other ships—had joined the Chesapeake crew.

“I know of no such men as you describe. . . . I am also instructed never to permit the crew of any ship that I command to be mustered by any other but her own officers. It is my disposition to preserve harmony, and I hope this answer to your dispatch will prove satisfactory.”

How mistaken he was.

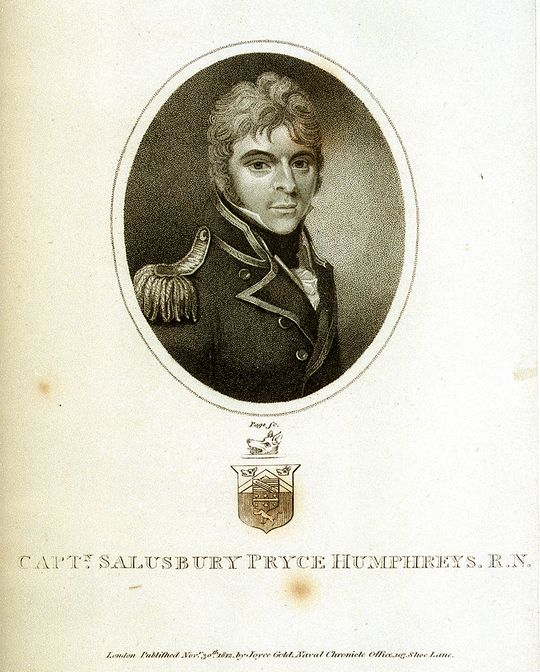

Humphreys resorted to a hailing trumpet in an effort to compel the American to submit, without effect.

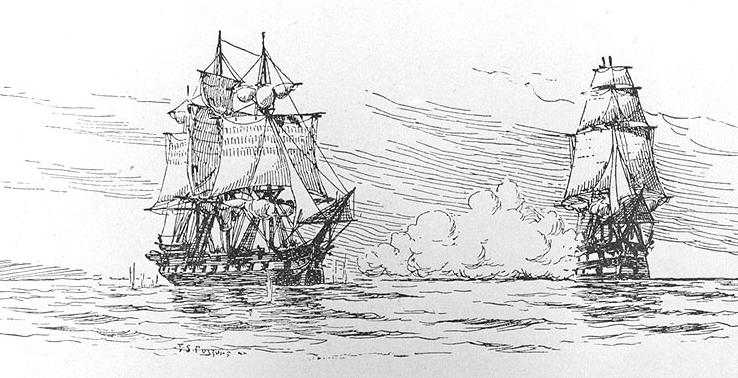

About an hour passed before the British ship fired a warning shot across Chesapeake’s bow and, when that failed to stop her, Leopard opened fire with broadsides. With her gun barrels empty, her green crew ill-trained and her decks prepared for a long transatlantic journey, Chesapeake managed only a single shot.

Four Americans were killed and 18 wounded in the brief but furious volley. Within 10 minutes of the first shot, a wounded Barron ordered Chesapeake’s colours struck and he surrendered. A boarding party then set out in search of deserters among Chesapeake’s ranks.

While scores of British nationals had signed on with Chesapeake, Humphreys detained only four Royal Navy deserters and, of those, Ratford was the only British citizen. The others—William Ware, Daniel Martin and John Strachan—were Americans whose service in the British navy had been brought about by force.

Two of them were African-Americans, which makes their decision to bolt back to a slave state all the more confounding, and perhaps a damning commentary on the Royal Navy’s notorious discipline of the day.

Ratford was discovered hiding in the coal hold below Chesapeake’s decks. “He said he was American, and did not belong to the Halifax,” said George Tincombe, the master’s mate who found him.

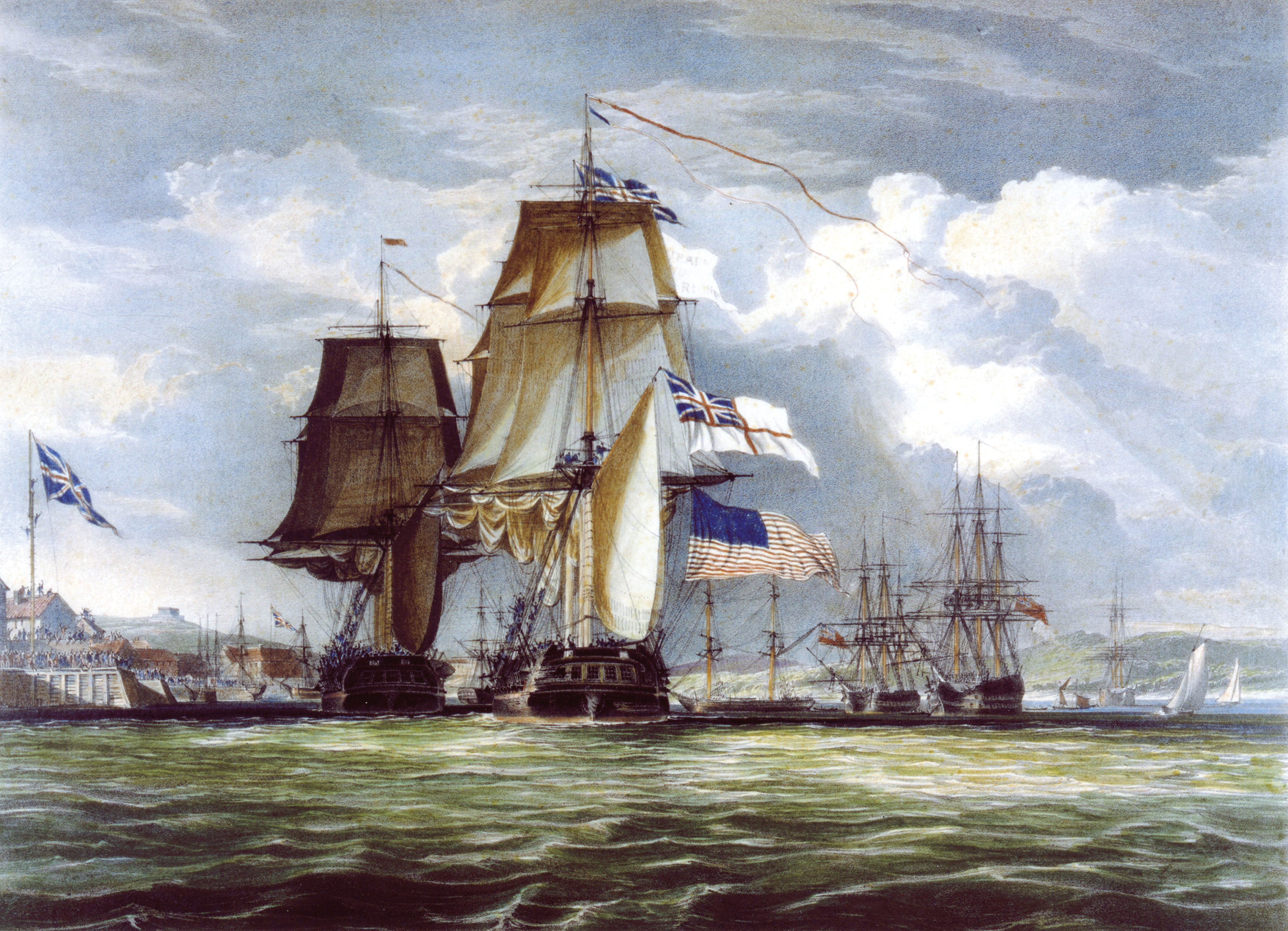

Chesapeake was then released and limped back to port. Less than a quarter-century after the War of Independence had ended, the incident caused a wave of popular and diplomatic outrage in the United States.

Among his most vocal critics was Commodore Stephen Decatur, a former subordinate and member of the panel that had court-martialed him. An outraged Barron challenged Decatur to a pistol duel. It was held March 22, 1820.

There were no paces; the two men faced off, with instructions to fire between the count of one and three. Barron was hit in the lower abdomen and into his thigh. Decatur got a ball around the pelvis, severing arteries. Both fell.

“Oh, Lord, I am a dead man,” Decatur exclaimed as he lay. Barron declared the duel properly and honourably executed and told Decatur that he forgave him from the bottom of his heart.

Decatur died the following day; Barron survived and, though he never sailed again, he went on to become the U.S. Navy’s senior officer. He died in Norfolk in 1851.

Back in Halifax, Ratford was brought to trial in short order. It lasted but a day. Though he’d been described by his midshipman, Turner, as a “steady, sober, attentive man” and one he could have entrusted onshore, Ratford was sentenced to death by hanging from the yardarm of one of His Majesty’s ships.

“You have now heard the awful sentence of the court,” the judge advocate told him. “You have been found guilty of deserting from the service of your country, which, at all times, is highly criminal. If it was possible to make it more so, it is, at the present crisis, when Great Britain is struggling for her very existence.

“Your deserting from the Halifax, and entering into the American Navy, has been attended with the most serious and unfortunate consequences, affecting the peace of both countries. The offences of which you have been found guilty are of so flagrant a nature, that I cannot flatter you with the least hopes of a pardon.

“I, therefore, earnestly recommend your employing the short time you may have to live in making your peace with Heaven.”

It was Wednesday. The following Monday, at 9:15 a.m., Ratford was hanged by the fore-yardarm of Halifax, a clear and sobering message to all who would consider “the continuance of an offence so hurtful to your country and disgraceful to the character of British Seamen.”

The other three deserters were sentenced to 500 lashes each, with the sentences commuted to prison time. After a storm of protest out of Washington, the last of them were delivered to Boston a month after the War of 1812 broke out.

The rest of Halifax’s deserting jolly boat crew—Saunders, Hubert, North and Hill—are all but lost to history.

“Never since the Battle of Lexington have I seen this country in such a state of exasperation as at present, and even that did not produce such unanimity,” said President Thomas Jefferson, who imposed an embargo on British goods.

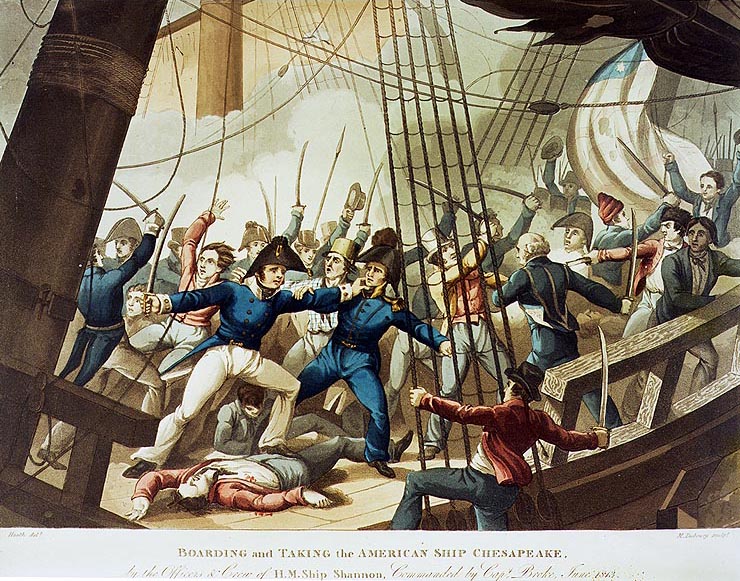

During the war that followed, Chesapeake was captured off Boston by a British frigate, HMS Shannon. The Royal Navy commissioned her, then put her up for sale at Portsmouth in 1819. The Chesapeake Mill in Wickham, England, was built from her timbers and still stands to this day.

Advertisement