Documentary filmmaker Garth Pritchard takes in the mountain vista southwest of Calgary, near the ranch he managed for years. [Stephen J. Thorne]

“F/8 and be there” has been Garth Pritchard’s camera-ready mantra over more than 50 years as a journalist, rancher and raconteur. And the robust Alberta-based filmmaker has been all over the world with Canadian troops, from Africa and Burma to Afghanistan and the Balkans.

Beloved by soldiers from one end of Canada to the other, Garth made it his life’s mission to tell their stories. Now, as the outspoken 75-year-old struggles to overcome the debilitating physical legacy of that quest, the Canadian War Museum has announced it has acquired the bulk of his work, a legacy for all Canadians.

The collection includes more than 400 hours of raw video footage and over 700 photographs of Canadian soldiers operating overseas—in Bosnia, Croatia, Burma, Kuwait, Somalia, Sri Lanka and Afghanistan, some of which is already on permanent exhibit.

The acquisition also includes footage he shot in Canada during the 1998 ice storm documenting the military’s emergency response along with field notes, articles and other documents.

“We are very pleased to acquire this trove of visual material from such an important documentary filmmaker and photojournalist,” said Caroline Dromaguet, the museum’s acting director general. “Pritchard’s unique first-hand perspective on the activities of the Canadian military is invaluable to the study of modern conflict, and we are proud to be able to add it to our collections.”

Garth Pritchard (left), Major Bob Ford and author Stephen J. Thorne in Eastern Afghanistan in 2002. [Stephen J. Thorne]

There are special bonds between those who share extreme experiences together. Garth Pritchard and I share those bonds. Ours is a friendship like no other that I know—challenging, combative, supportive, respectful, loving and enduring.

I met him in 1999 in Kosovo, where we often found ourselves working side-by-side, me interviewing, Garth filming and interjecting with his own queries and insights, all the while cursing a wire-service photographer who kept getting in his shot. (It wasn’t me.) We would go on to work together in Afghanistan, where he shared sources and opened doors. As a filmmaker, he was unconcerned that a daily news journalist like me posed any kind of a threat to his long-term projects.

He did not suffer fools gladly, and an endorsement from the quintessentially curmudgeonly Garth was an endorsement indeed: a ticket to people and places and the accompanying opportunities to show who you are and what you’ve got which, if you had the chops, created more opportunity.

This generosity didn’t come freely or easily; Garth’s respect and friendship were earned through blood, sweat and tears—and we shared many.

Throughout his career, Garth was a marvel of Mother Nature, earning the respect and admiration of new generations of troops, partly by sticking to his other credo, “one man, one kit.” That meant he always humped his own equipment and never allowed a Canadian soldier to carry it for him, though they were always willing.

By the time he started working in Afghanistan in 2002, however, he was in his late 50s and the heat, the hills and the army rations had become just a little less appealing. Nevertheless, he pressed on, travelling to the war zone for six extended stays over 10 years. He produced three documentaries for History Television under the banner Canadians in Afghanistan and, along with myself, co-anchored an award-winning Canadian War Museum exhibition, Afghanistan: A Glimpse of War.

He received 14 awards for six of his documentaries, including the Ross Munro Media Award for defence reporting in 2003, which recognized not only his Afghanistan work but a career devoted to military coverage.

A master of the one-liner, Garth had eaten so many chemically rich, preservative-laced Meals Ready to Eat, or MREs, and Individual Meal Packs (IMPs) over the decades that he used to say, “My colon has a half-life of 65,000 years.”

It was age and the Burma trip that ultimately ended his forays. In making the 1997 film Lost Over Burma: Search for Closure, Garth had followed an expedition into the Burmese jungle to recover the remains of a six-man RCAF crew lost during the Second World War.

He didn’t know it then, but he picked up a parasite that didn’t show itself for 20 years. When it finally did, it did so with a vengeance, attacking his liver, shutting down organs and hospitalizing the previously unstoppable force for months. Garth has been in and out of care for two years now, overcoming the most dire prognoses and, though progressively weakened, bouncing back each time, thanks largely to the love and care of his devoted wife, Sue Archibald.

“Improving slowly,” came news from Sue after a recent setback. “Getting stronger every day.”

Garth Pritchard (left) and Sue Archibald with the author in December 2017, shortly before Garth was struck by a parasite he picked up in Burma. [Stephen J. Thorne]

War photographer Robert Capa famously said, “If your photographs aren’t good enough, you’re not close enough.” Garth’s cinéma vérité style of filmmaking was distinguished by his access—up close and personal with vivid audio clips and soldiers’ voices unfettered by excessive narration. He got to know his subjects intimately, and they knew him.

“I’ve watched Canadian troops all over the world,” he told me in 2002, when ‘Garth Pritchard’ was practically a household name among Canadian soldiers. “Their professionalism at so many levels has made me proud to be Canadian. They always leave things better than they found them.”

His documentaries about Canadian peacekeepers constitute an invaluable record of Canada’s role in United Nations blue, starting in Bosnia with Caught in the Crossfire. He documented the life and death of Master Corporal Mark Isfeld in The Price of Duty, the trials and tribulations of padre Mark Sargeant in the film In God’s Command, and the grim work of a forensic team sifting through the mass graves of Kosovo in Shadows of War.

In February 2002, he recorded Canadian regulars firing their first shots of the Afghanistan war as armoured members of the Lord Strathcona’s Horse (Royal Canadians) pinned down two suspected enemy minelayers.

No conversation with Garth on the subject of Afghanistan passes without the information that he was the first noncombatant to join Canada’s first combat assault since Korea. It was March 2002, and he was one helicopter ahead of me.

He kept up with soldiers half his age throughout the five-day operation, hauling gear up and down rocky cliff faces and regaling Canadian combat engineers and U.S. Navy SEALs with stories, all the while recording theirs.

Garth Pritchard arm wrestles mujahedeen guard Abdul in Kandahar in 2002. [Stephen J. Thorne]

At the sprawling military base south of Kandahar, he was welcomed at virtually every table and tent by coalition troops of all nationalities. His access was extended even to the operating room, where he filmed doctors saving lives following the friendly-fire incident that killed four Canadians and wounded eight.

Garth had a special affection for the Strathconas because, he would jest, they’re mechanized—their Coyote and Bison armoured vehicles had eight wheels each to carry him and his gear wherever the story summoned him.

“A guy’s gotta know which side his bread is buttered on,” he admitted, even to the infantrymen who razzed him endlessly about his weakness for wheels.

Back in Kandahar, I had a house with a staff that included a fixer, two mujahedeen guards, and a cook whom we knew only as Baba, the name reserved for white-bearded men of distinction. Standard fare was lamb or beef kabobs and rice. But Afghan potatoes were exquisite, and Garth came over and taught Baba how to make the best French fries I’ve ever had, bringing a little bit of Canada to the adobe-walled compound I called home for much of my first trip over.

He also taught Abdul, my massively bearded, fire hydrant-built guard, how to arm wrestle. Garth beat him, and Abdul wasn’t impressed. I thought there’d be trouble until Garth disarmed him with a joke and all was right with the world again.

He started in the 1960s as a photojournalist with the Montreal Gazette when separatist fervour was building. Garth was in his journalistic element.

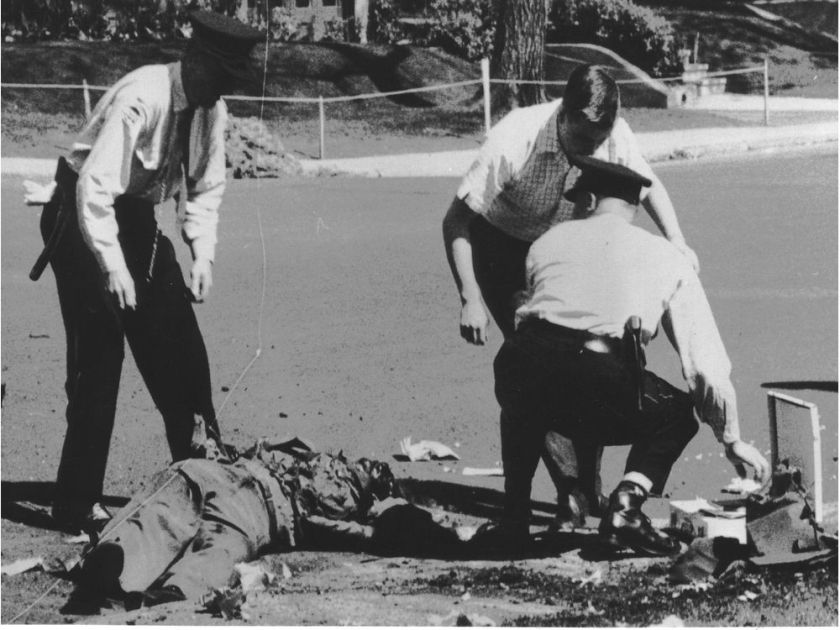

He recorded two indelible images from those troubled times—a separatist bomb going off in the hands of Sergeant-Major Walter (Rocky) Leja, a demolition specialist, in 1963 and the body of FLQ kidnap victim Pierre Laporte in a car trunk in 1970.

As a writer and photographer, he covered a broad range of events, including the Montreal Canadiens’ glory years and the Montreal Expos’ first-ever major league game at old Jarry Park. Eventually, he left for the Calgary Herald.

But journalism was changing and Garth was becoming disenchanted and disenfranchised by the new waves of journalism-school graduates. He left the trade and worked as photographer to former prime minister Brian Mulroney before returning to help his old friend Jimmy Duff start a newspaper in Montreal, the short-lived Daily News.

Sergeant-Major Walter Leja, an army demolition expert, lost his left hand and suffered severe face and chest injuries when a bomb planted by FLQ terrorists in a Westmount mailbox exploded as he was dismantling it on May 17, 1963. This photo, taken seconds after the explosion by Garth Pritchard of the Montreal Gazette, received The Canadian Press picture-of-the-month award for May 1963. [GARTH PRITCHARD/GAZETTE]

Garth began documentary filmmaking in the late 1980s and has worked solo for much of his film career, for better or worse. In the early years, Sue repeatedly used her new-house fund to finance his far-flung travels.

Garth’s rich life hasn’t been restricted to journalism and filmmaking either. He did a stint as a lodge cook in the Rocky Mountains, worked in the pit crew of a second-place car at 1969’s Daytona Continental endurance race (now known as the Rolex 24 at Daytona), and spent three months chasing wild horses in Suffield, Alta., saving 1,201 of them from a death sentence.

For years, he was caretaker of a heritage ranch in the mountains west of Priddis, Alta., where Sue, an artist, horsewoman and retired corporate administrator, kept her animals. A few years ago, the couple got a place of their own alongside the Bow River near Carseland, Alta., a cozy little hamlet 70 kilometres southeast of Calgary. They were planning some leisurely travel when Garth became ill.

He has been visited in the hospital by generals, junior officers and enlisted men alike. Doctors told him after his latest setback that he wouldn’t walk again. On Oct. 1, he walked, calling it “the greatest day of my life, ever.”

“It’s not over,” he said, adding, “I hope somebody steps into where I was and tells Canadians what their soldiers are doing all over the world. I tried my best.”

Advertisement