For thousands of years, men on horseback were an essential part of warfare. Mounted soldiers—cavalry—were scouts, reserves or attack forces, used when speed, shock action or long distances were involved. The cavalry was a proven and necessary component of most armies.

The face of warfare changed dramatically early in the First World War, as machine guns, barbed wire, trenches, minefields and artillery barrages led to huge increases in casualties and severely restricted mobility, a key advantage of cavalry.

The cavalry generals, however, were not yet ready to concede that the day of the horse was over and give up their beloved mounts. As a result, long after the war started in 1914, all the belligerents maintained cavalry. For much of the war, most mounted units were held in reserve, waiting for the holy grail of a gap to appear in enemy lines, through which they could charge to rear areas.

But then, in the final year of the war, a rare opportunity arose to employ mounted units in their classic role—and Canadian cavalry made history.

At 4:40 in the morning on March 21, 1918, more than 6,000 German guns started a six-hour bombardment with high-explosive and gas shells along 100 kilometres of the British lines held by Third and Fifth armies stretching southward from Arras, France, along the old Somme battlefield. Witnesses described it as the fiercest barrage of the war to date. At 9:40, German soldiers from 32 assault divisions followed and quickly overran forward positions. Operation Michael, a surprise attack on the Western Front, had begun.

With Russia out of the war (the Imperial Army disintegrated following the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917), American forces not yet involved in strength, and the French Army severely weakened by mutinies, Germany was desperate to gain the upper hand and hoped Operation Michael would be part of its final grand offensive. Because the Germans were not strong enough to mount a general offensive along the entire front, five separate offensives were planned. Operation Michael was the first—and the biggest.

This massive assault was aimed at the juncture of the British and French armies, always a potential weak spot. Its objective was to force the British north toward the English Channel ports and the French south toward Paris.

General Herbert Gough’s Fifth Army was weakly spread out along 65 kilometres of the front, much of it in poorly constructed former French positions. Faced with an overwhelming German advance, British units were overrun, decimated or forced back. Fifth Army virtually collapsed, leaving the right flank of General Julian Byng’s Third Army exposed and forcing some of its divisions to withdraw. Confusion reigned along the British front. In desperation—and to more effectively co-ordinate their efforts—the Allies appointed French Marshal Ferdinand Foch as commander-in-chief on the Western Front on March 26.

The Canadian Cavalry Brigade (CCB) had been operating in several roles in the southern part of Fifth Army’s sector. Gough called on the CCB, commanded by British Brigadier-General Jack Seely, to halt the Germans.

At the time, the CCB consisted of the Royal Canadian Dragoons, Lord Strathcona’s Horse (Royal Canadians), Fort Garry Horse and a machine-gun squadron. Known respectively as the Dragoons, Strathconas and Garrys, each regiment had three 150-man squadrons, each comprised of four 36-man troops. All three cavalry regiments were under strength at the time, some by as much as half.

Meanwhile, the spearhead of the German advance rolled toward one of its intermediate objectives: the important rail centre of Amiens, roughly along the line of the boundary between the British and French armies. On March 29, a five-kilometre gap opened up in the Allied line, centred on a tree-covered ridge.

The next day—Easter Sunday—the Canadians awoke to a cold, foggy dawn, the sun hidden behind a heavy mist. The troops anticipated moving shortly, but when the order came that any move would be delayed by two hours, they received a much-welcomed hot breakfast of bacon, washed down with strong tea.

Early that morning, German battalions from the 23rd (1st Royal Saxon) Infantry Division had begun to occupy Moreuil Wood, on a commanding ridge on the right bank of the Avre River overlooking the small village of Moreuil, a mere 20 kilometres upstream from Amiens.

While low-flying Allied aircraft bombed and strafed the Saxons, the 243rd Württemberg Division headed toward the ridge, marching in two columns. The objective of the left-hand column was to seize Moreuil and force a river crossing, while the right-hand one was to take the wood and the ridge.

As British troops pulled back along the front in reaction to the German onslaught, the Canadian cavalrymen were sent west of Moreuil to await further orders. They were not long in coming.

– Illustration by Sharif Tarabay –

The charge of the Canadian Cavalry Brigade (CCB) at Moreuil Wood in France on March 30, 1918, was neither the first nor the last Canadian cavalry charge in the First World War, but it was the biggest. The CCB fought dismounted as infantry until January 1916, when its beloved mounts were returned to it.

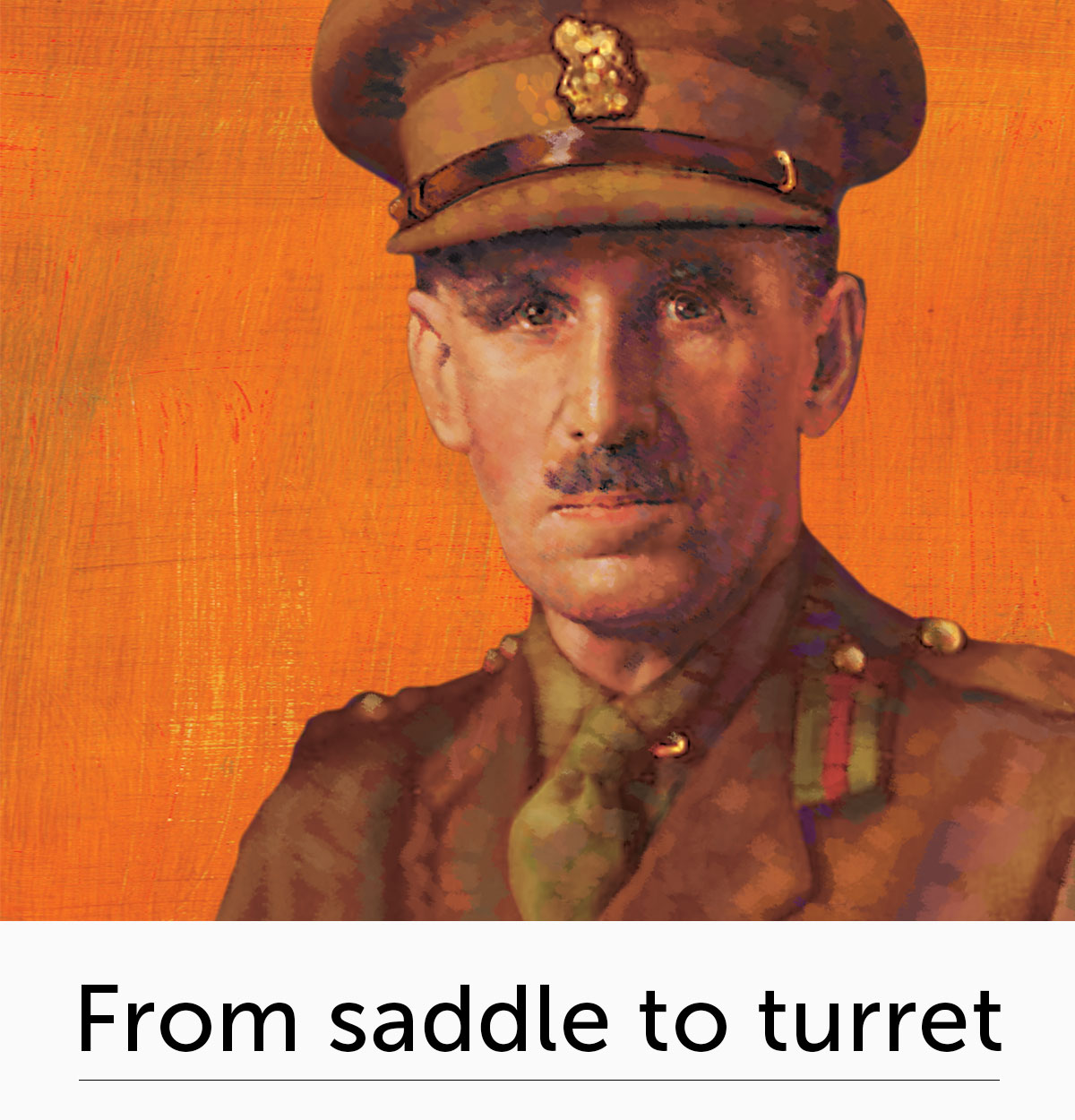

Its first mounted operation was during the German retreat to the newly constructed Hindenburg Line in early 1917, which provided the opportunity for minor actions. On March 27, Lieutenant Fred Harvey (right) of the Lord Strathcona’s Horse (Royal Canadians) received the Victoria Cross for riding against a machine-gun position and capturing it at the village of Guyencourt.

On Nov. 20, Lieutenant Harcus Strachan, in command of B Squadron of the Fort Garry Horse, led his troopers behind enemy lines near Cambrai and then overran a German artillery battery. Strachan also received the Victoria Cross.

In the war’s closing days, the CCB saw action at the Battle of Amiens on Aug. 8, 1918, and during the advance toward Le Cateau and beyond on Oct. 9 and 10. Its last actions before the Armistice saw it clear six villages and capture several prisoners, artillery pieces and machine guns.

But the days of cavalry were over. The First World War witnessed the sunset of the horse as a weapon of war, to be replaced by the clanking, smoky, slow-moving armoured monsters eventually known as tanks. Although they were first employed at the Battle of the Somme in 1916, not enough tanks were available there to break through enemy lines. Ironically, their first concentrated use was at Cambrai in 1917, when 378 fighting tanks smashed through German front line defences as Strachan’s squadron of Garrys rode behind enemy lines nearby. Canada raised three tank battalions late in 1918, but none of them made it into combat.

Photo: Lieutenant Frederick Harvey captured a machine gun that was causing heavy casualties in an attack on Guyencourt, France, on March 27, 1917. He received the Victoria Cross.

At 8 a.m., Seely was ordered to move forward to support French infantry in the area of Castel, just west of and across the Avre River from Moreuil Ridge. Leaving the CCB to follow later, Seely rode off on his charger, Warrior, to conduct a reconnaissance, taking with him his brigade major, aide and signal troop. When Seely arrived at Castel, he found the French about to withdraw.

Seely convinced the French divisional commander to remain, promising he would attack the ridge shortly and needed the French to provide supporting fire. He quickly devised a plan and passed it to his brigade major to brief the CCB units as they arrived in Castel.

Meanwhile the CCB was on the march. The Dragoons led, followed by the Strathconas and then the machine-gun squadron, with the Garrys bringing up the rear.

Seely galloped up the ridge through enemy fire to set up his headquarters in a small outgrowth known as the Bois de la Corne at the northwest corner of Moreuil Wood, which the Germans had not yet occupied. Five of his 12-man brigade signal troop were cut down by enemy fire as they dashed toward the small copse. By 9:30, Seely was in location, a red pennant jammed into the ground marking his headquarters.

Moreuil Wood was a triangle-shaped wood, with its 1,500-metre-long sides facing north, west and southeast. It consisted largely of ash trees not yet in leaf, but heavy undergrowth and the closeness of the trees made riding through it extremely difficult.

Seely planned to send mounted thrusts by three Dragoon squadrons into the wood. A and C squadrons would go along the north and west sides respectively, while B would charge into the middle. The Strathconas would clear the wood from north to south in a dismounted action, while the machine-gun squadron would provide covering fire on the flanks. The Garrys would remain in reserve.

The Dragoons led. The three Dragoon squadrons deployed roughly as ordered. A Squadron made it well into the woods, dismounted and drove some 300 Germans from the trees. The other two squadrons of Dragoons were not as successful.

C Squadron ran into a German infantry battalion and its supporting artillery battery and was cut to ribbons at the southwest tip of the wood, while B Squadron—reduced to 80 men—entered the northern side halfway along it and immediately ran into heavy German opposition, halting further progress.

As an intense battle raged among the trees, the Strathconas crossed the bridge and formed up along the north face of Moreuil Wood. Their commanding officer ordered A and B squadrons to attack dismounted to help the Dragoons’ B Squadron, but wisely kept C Squadron as a mounted reserve.

Because the attack of the Dragoons’ B Squadron had stalled, the Strathconas’ C Squadron was soon required. The commanding officer ordered it to gallop around the northeast corner and prevent German reinforcements from entering the wood.

– Illustration by Sharif Tarabay –

Born: January 2, 1885, in Billingford, Norfolk

Died: March 31, 1918 (aged 33) in Moreuil, France

Buried: Namps-au-Val British Cemetery in France

Unit: Lord Strathcona’s Horse (Royal Canadians)

Flowerdew ordered three troops of his squadron to attack two lines of German infantry that were preparing to take Moreuil Wood. His charge caused heavy casualties on both sides, but forced the enemy to retire. He was mortally wounded in the action.

C Squadron was commanded by Lieutenant Gordon Muriel Flowerdew, 33, a British-born British Columbia fruit farmer, excellent horseman and pre-war Canadian Militia cavalryman. Because Germans occupied the northeast corner, Flowerdew first sent 2nd Troop ahead to seize it. The troop was under Lieutenant Fred Harvey, 30, who had earned the Victoria Cross a year earlier at the village of Guyencourt.

On the way, Harvey and his men sabred five Germans who were looting a French supply wagon. As he neared his objective, Harvey dismounted his men to attack additional Germans in the wood when Flowerdew rode up.

Harvey briefed his squadron commander, who told him, “Go ahead and we will go around the end mounted and catch them when they come out.” Flowerdew then returned to C Squadron, waiting nearby in an area of low ground.

Flowerdew led his men out of the draw and up a steep embankment. As they reached the higher ground, they saw perhaps 300 German infantrymen deployed in two lines in the open some 300 metres to their front, supported by an artillery battery and a machine-gun company.

Flowerdew waved his sword in the signal for the squadron to deploy into line, turned in his saddle and shouted, “It’s a charge, boys, it’s a charge!” Riding directly behind him, Reg Longley, the squadron’s boy trumpeter, raised his horn to blow the charge but no sound came, as horse and rider were shot down.

Although it was certain death, the Strathconas galloped bravely forward, sabres drawn, directly into intense rifle, machine-gun, mortar and artillery fire. The charge took a terrible toll on men and horses.

“Everything seemed unreal,” recalled Private Albert Dale. “The shouting of the men, the moans of the wounded, the pitiful crying of the wounded and dying horses.” Sergeant Tom Mackay later counted 59 bullet holes in one leg; the holes in the other could not be tallied as they ran into each other.

As the squadron neared the first line, Flowerdew went down, wounded in the chest and both thighs. The squadron flooded past him, cutting down more than 70 Germans with their sabres.

Only one Strathcona made it through both lines. When Sergeant Fred Wooster of 1st Troop found himself alone after running his sabre through one German and clubbing another on the head, he made his way back to Seely and reported the situation before joining Harvey’s troop.

Superior horses

“In peace so often practised and in war so rarely used, the command ‘attacking cavalry to right’ could now be used. As if electrified, the gun trails flew to the left, and with lightning-like quickfire, the two guns opened fire at a range of 400 metres

at the attacking squadrons.

“In a few minutes one could only see a few riderless horses still heading toward our gun lines. The greatest part of the riders lay dead or wounded on the ground. A few lucky ones were able to escape this fate through quick retreat. The drivers of the 1st Battery were able to capture about 20 horses that were very welcome as replacements for the many horses lost by us. As expected, these horses that had been bred on the Canadian steppes distinguished themselves from our horses, because of their superior nutritional condition.”

—Excerpt from a war diary of Germany’s 238th (Württemberg) Field Artillery Regiment describing the Battle of Moreuil Wood

Meanwhile, about 20 Dragoons had also joined Harvey at the northeast corner of the wood. Two of Harvey’s group retrieved Flowerdew and handed him over to four others who carried him back to the CCB’s field ambulance. As they evacuated Flowerdew, the sun finally broke through the mist, lighting up the battlefield.

To assist the troops still fighting inside Moreuil Wood, Seely committed his reserve. B Squadron of the Garrys circled south along the west bank of the Avre to bring fire to bear on the southwest corner of the wood, while A and C were sent into the wood.

Intense fighting continued for a couple of hours, until the British 3rd Cavalry Brigade arrived about noon and, along with the Canadians, succeeded in pushing the Germans to the very southern edge of the wood. Together, they held out against several counterattacks until relieved that night about 9:30.

Losses for all three regiments were severe, in the order of one-third to one-half of their strength. Hardest hit of all was Flowerdew’s squadron, which lost more than 70 per cent of its men.

On March 31, the Germans recaptured most of Moreuil Wood and occupied Rifle Wood, a smaller copse nearby to the northeast. The next day, two British cavalry brigades and the Canadians attacked Rifle Wood in a dismounted action and recaptured it.

Flowerdew died of his wounds on March 31, at the same time as his promotion to captain was announced. For his gallantry in leading what became, if not the last great cavalry charge in history, certainly one of the last, Flowerdew was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross.

By this time, German supply lines were thinly stretched and the troops exhausted. The German high command ended Operation Michael on April 5. Canadian cavalrymen had played their full part in the defeat of Germany’s last great offensive of the war.

Advertisement