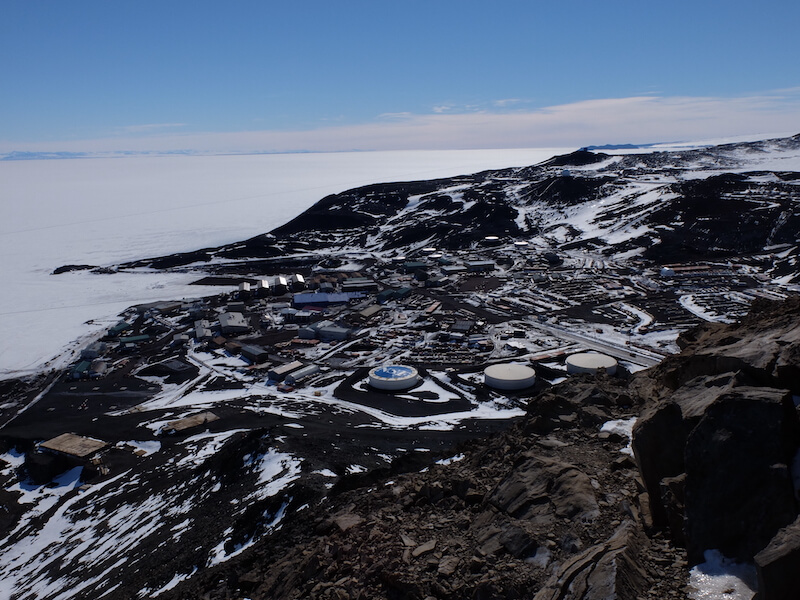

McMurdo Station, the largest research station in Antarctica. [Wikimedia]

With 12,512 warheads and counting worldwide, it’s hard to imagine that more than 60 years ago the planet’s leaders signed an agreement that effectively bypassed the territorial sovereignty and military-industrial development of 10 per cent of the Earth’s land mass for the benefit of scientific achievement, environmental preservation and peace.

Signed in 1959 by Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Chile, France, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, South Africa, the United Kingdom, the United States and the USSR, the Antarctic Treaty was a welcome surprise during Cold War tensions.

“The fact that the U.S. and the Soviet Union managed to put aside their differences at the height of the Cold War surprised many and makes the achievement of the group truly remarkable,” wrote David Nikel, a senior contributor to Forbes magazine.

After coming into force on June 23, 1961, the Antarctic pact remains not only one of the most successful international agreements ever, but the first nuclear arms control agreement in history; however, it took decades to create.

However, without clearly defined territories, the nations soon clashed over each other’s geographical positions.

The U.S. delegate Herman Phleger signs the Antarctic Treaty in December 1959. [Wikimedia]

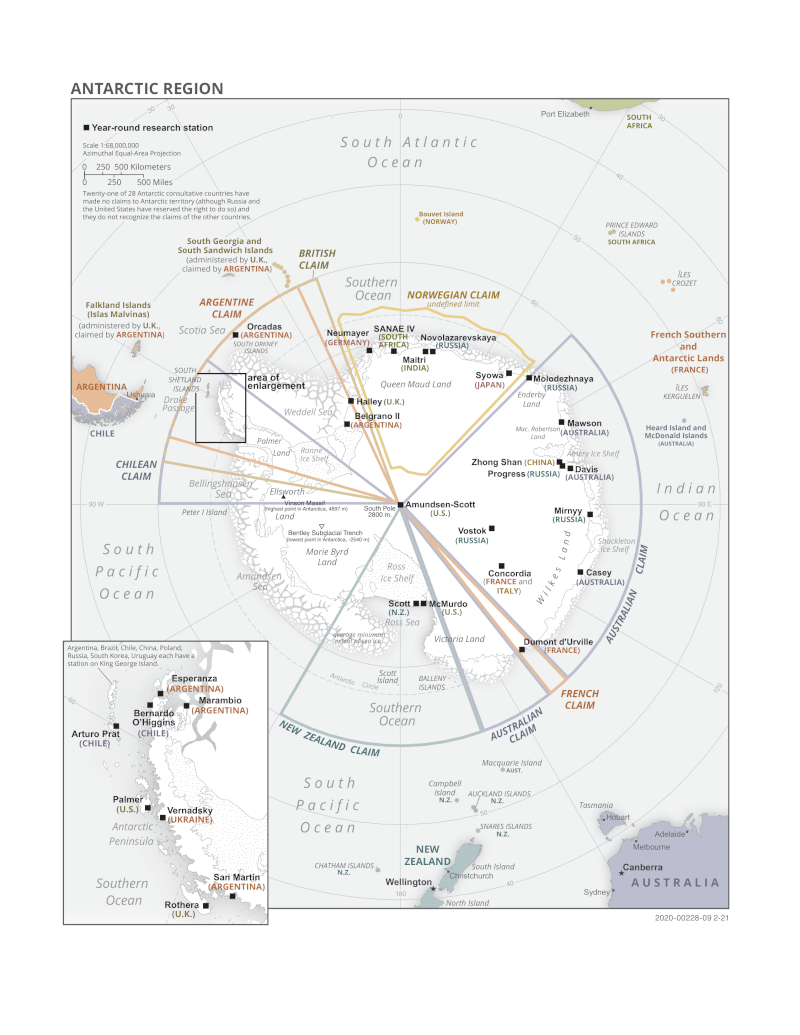

At the start of the International Geophysical Year (July 1957-December 1958), participating countries began setting up research stations across Antarctica as part of an international study of Earth’s planetary environment. However, without clearly defined territories, the nations soon clashed over each other’s geographical positions, especially regarding the highly sought-after Antarctic Peninsula.

To facilitate better coordination and collaboration between nations, the International Council of Scientific Unions established the Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR) in 1958. It remains active today.

With the advent of SCAR, U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower hosted the Antarctic Conference in Washington for the 12 nations that had active research programs on the continent, seven of whom also had existing territorial claims.

The meeting’s focus, however, was less on validating age-old land grabs than it was on ensuring peace between nations. To do this, a treaty was drafted that emphasized harmony, while banning military activity, including weapons testing, establishing military bases or disposing of radioactive material. In 1991, an additional protocol was signed that banned mineral and oil exploration for 50 years. That will be reviewed in 2048.

Map of research stations and territorial claims in Antarctica, as of 2015. [Wikimedia]

As 2048 approaches, the future of the icy continent becomes more uncertain.

The Antarctic Treaty has now been signed by 50 nations, with Canada being a non-consultative party since 1988. More than 20 Canadian universities and six federal government organizations are associated with Antarctic researchers, and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada continues to increase its funding there.

“Antarctica is ground zero for understanding global change effects on society,” Roberta Marinelli, the director of the U.S. National Science Foundation Office of Polar Programs, told media outlet MercoPress.

As 2048 approaches, the future of the icy continent becomes more uncertain.

“The reason 2048 looms large is because if certain countries feel that the prohibition on mineral exploitation is no longer to be respected, people worry that the whole thing could unravel,” geopolitics professor Klaus Dodds told BBC.

Similarly, the discovery of archeological remains, like a skull found on Antarctica’s Yamana Beach in 1985, may complicate territorial claims.

“I could see straight away it would inflate territorial nationalism,” Dodds continued.

Still, as it celebrates its 62nd anniversary, the Antarctic Treaty serves as a poignant reminder that countries can unite for the greater good.

Advertisement