On Feb. 11, 1900, the 1,039-strong Canadian contingent recently deployed to South Africa joined a powerful British column at Graspan, on the Cape Colony’s eastern boundary with the Boer Orange Free State. The following day, under a blazing sun with temperatures peaking at 46°C, the 2nd (Special Service) Battalion, Royal Canadian Regiment (RCR) marched through thick, choking red dust across the veldt for about 20 kilometres to Ramdam—a Dutch homestead reduced to a burned-out ruin by British advance scouts. Here, 30,000 soldiers, 7,000 non-combatants, 14,000 horses, and 22,000 mules and oxen hauling 600 wagons and several artillery batteries staggered to an exhausted halt. Between Ramdam and the objective of Bloemfontein lay 200 kilometres of parched and rugged countryside.

Retreating south from where it had been besieging Mafeking—the northernmost Cape Colony town—and now threatened by the advancing British was a Boer force of about 5,000 commandos, accompanied by several dozen women and children, more than 400 wagons and several thousand horses. Boer commander General Piet Cronjé hoped to slip past the British and establish a blocking force to protect Bloemfontein until he could be reinforced.

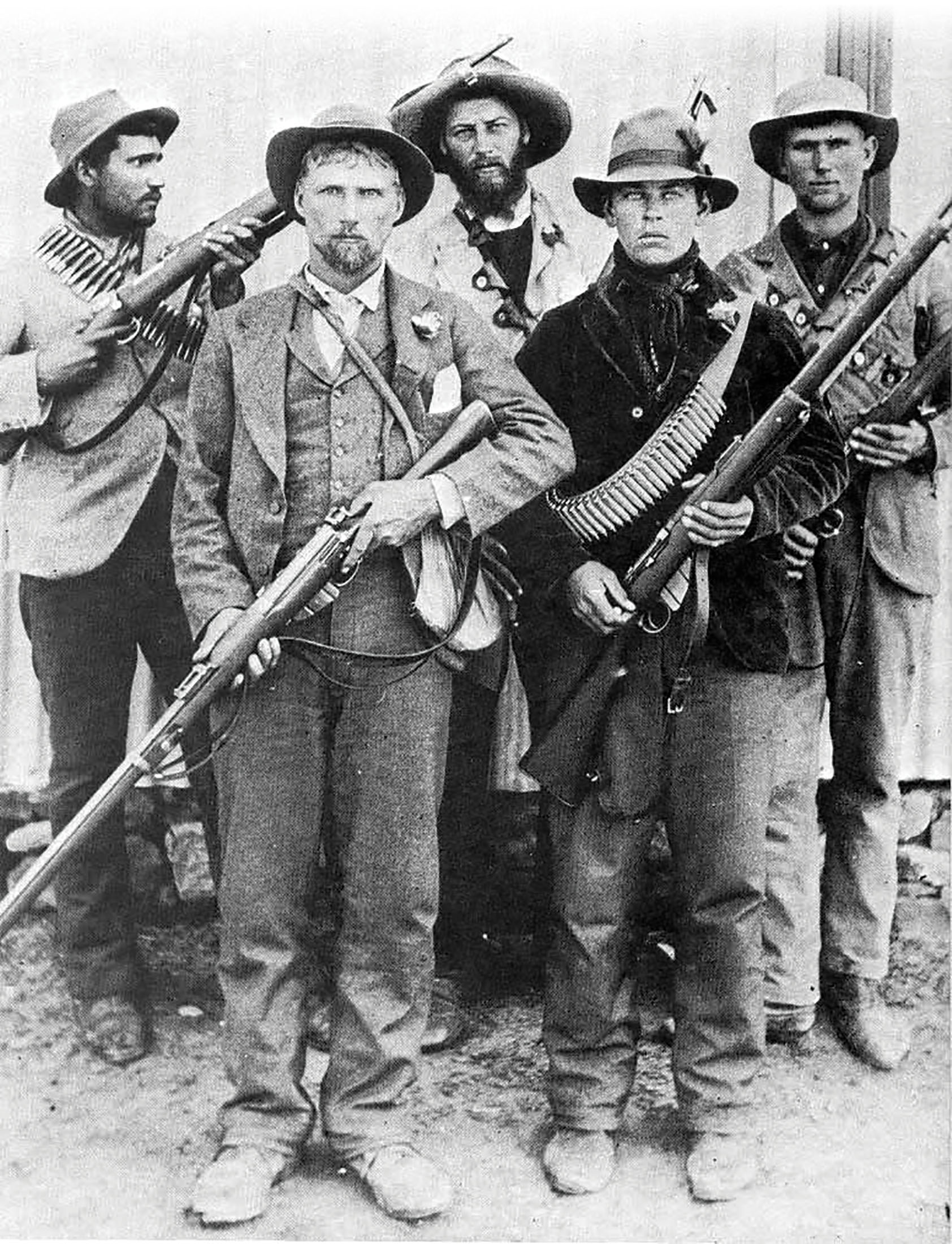

Boer soldiers, including this commando group, were adept at guerilla warfare—something the British had difficulty countering. [Alamy/E1GG2T]

Although the Boer retreat was stealthy, nothing could prevent the rising dust clouds. On Feb. 16, Cronjé’s Boers were detected by British scouts and skirmishing broke out. Several kilometres east of the Paardeberg (Horse Mountain) Drift—the Boer term for a ford—across the Modder River, Cronjé still believed escape was possible. Expecting to easily cross the river the next morning, then gain the road leading to Bloemfontein to continue an orderly withdrawal, Cronjé encamped his weary force.

It was a fateful decision, one that spelled disaster for the Boers, enabled the British to win their first decisive victory in South Africa, and provided Canadian troops with their first major engagement in an overseas war.

The roots of this war traced back to 1835. Rejecting British attempts to extend their authority over the Dutch colonists and considering themselves increasingly politically marginalized, about 15,000 Voortrekkers crossed the Orange River to leave Cape Colony and establish independent republics. Transvaal and the Orange Free State were recognized respectfully and reluctantly by Great Britain in the 1852 Sand River and 1854 Bloemfontein conventions.

Key players in the conflict included from (L-R) Paul Kruger, Transvaal president from 1883 to 1900, British Major-General E.T.H. Hutton, who leaked plans for a Canadian force and South African General Piet Cronjé. [Frederick S. Lee/LAC/e002505778; Alamy/EF98FJ; Topley Studio]

Both republics constituted attempts to continue the agrarian life that the Dutch colonists had maintained since their forebears had settled in South Africa in the 17th century, which they saw as being threatened after the British seized the Cape settlement in 1795. In 1814, the British takeover of the Cape from the Dutch was formalized by the Congress of Vienna. The Voortrekker movement was a repudiation of spreading British influence. Most Boers were deeply religious, adhering to a strict Calvinism that was intolerant of other faiths. After almost 200 years of warfare with African tribes, they were tough and uniquely adept at guerilla fighting that relied on riding skills, deadly marksmanship and superb tactical use of ground. Every adult male belonged to a “commando” military formation.

The Boers hoped their flight would free them of British influence and encroachment on their new lands, but the 1867 diamond discovery quickly led to the British annexing Transvaal in 1871. By December 1880, efforts to get the annexation reversed had failed and the Boers resorted to armed resistance. At Majuba Hill on Feb. 27, 1881, they dealt a large contingent of British regulars a stunning defeat that led to the Pretoria Convention a few months later. Although the convention did not reinstate full independence, it did grant the Boers significant control over their affairs and land.

In 1886, Anglo-Boer relations were again shredded by the discovery in Transvaal of the largest gold reserves on Earth. Seeking to limit the threat from the influx of gold seekers to the national identity of “God’s people,” as Transvaal’s President Paul Kruger called the Boers, he enacted legislation restricting the franchise to men who had been resident at least 14 years. This effectively limited it to Boers. To protect Transvaal’s railroad link to Johannesburg from being undercut by encroaching Cape railways, he also imposed what the British considered exploitive tariffs.

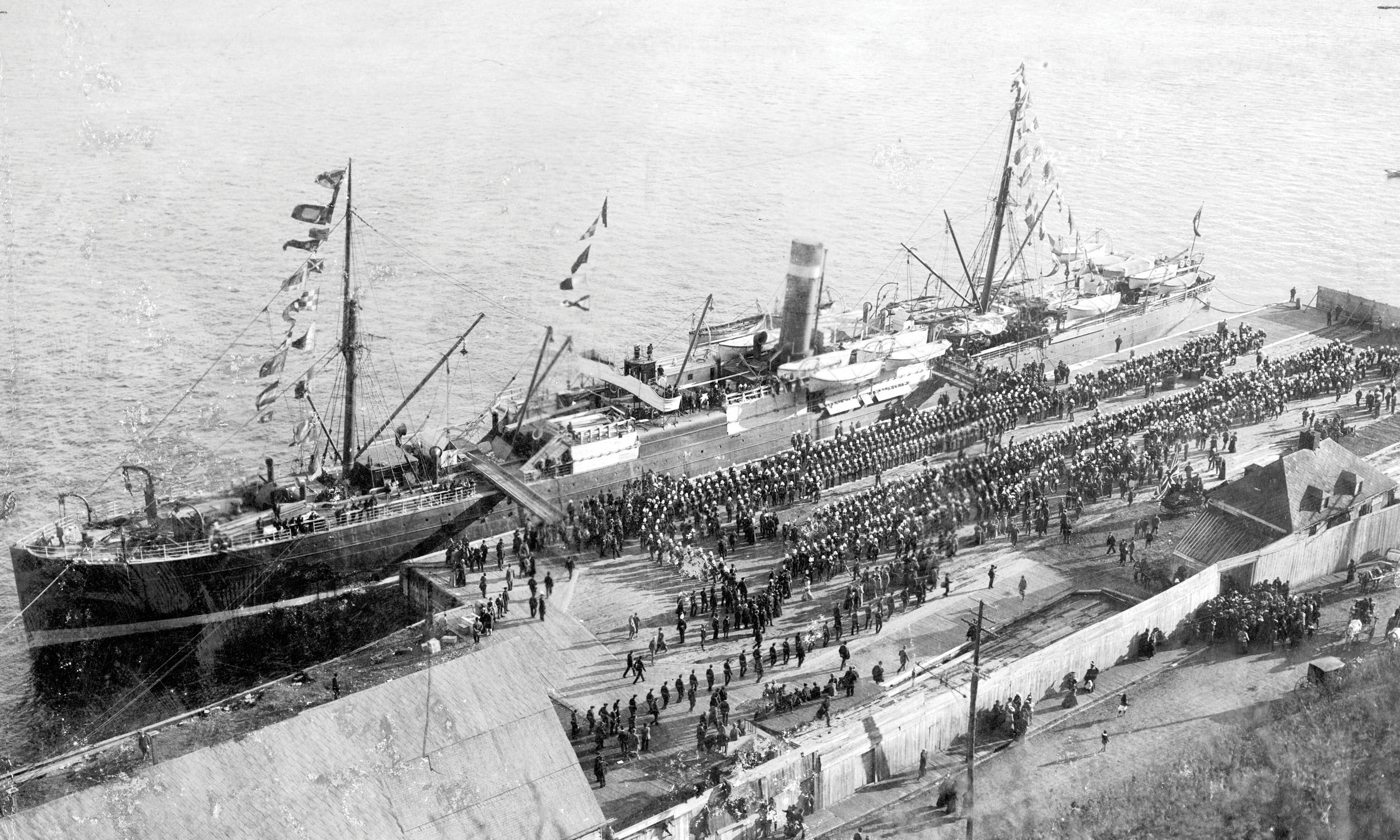

Canada’s first contingent in the Boer War, the Royal Canadian Regiment boarded HMS Sardinian in Quebec City on Oct. 30, 1899. [Wikimedia]

On the opposing side stood Cape Colony Prime Minister Cecil Rhodes, who sought to not only expand his personal gold interests but also to unite all of South Africa under the British crown. In 1895, with full knowledge of British colonial secretary Joseph Chamberlain, he attempted a coup that failed miserably. Rhodes was forced to resign, but the new Cape Colony governor and high commissioner, Sir Alfred Milner, continued to demand that the enfranchisement qualification be lowered to five years.

During negotiations in May 1899 at Bloemfontein, Kruger offered a seven-year compromise that Milner rejected. While hurriedly preparing for war, Britain set about drafting an ultimatum that Kruger pre-empted with one of his own issued on Oct. 9, 1899; he demanded the withdrawal of all British troops from the border. Two days later, the Boers launched a spoiling attack against British troops mustering on the border of Natal and the Second Boer War began.

Support for crushing this Boer uprising was strong throughout the British Empire. The Boers were demonized as roughshod peasants oppressing English-speaking settlers and prospectors. Such oppression, claimed an editorial in the Vancouver Province, “by a horde of ignorant Dutch farmers” was an insult to the empire. The Boers were viewed with contempt and a quick, decisive victory was expected. After all, how could a bunch of Dutch farmers stand against the world’s mightiest power? This was the height of New Imperialism, with European powers vying to expand their grip across the globe, and Britain led the pack. The rewards were captive markets, resource wealth and blocking the growth of rival nations. Africa was at the centre of this struggle, with France, Portugal, Spain, Italy, Germany and Britain all competing for colonies.

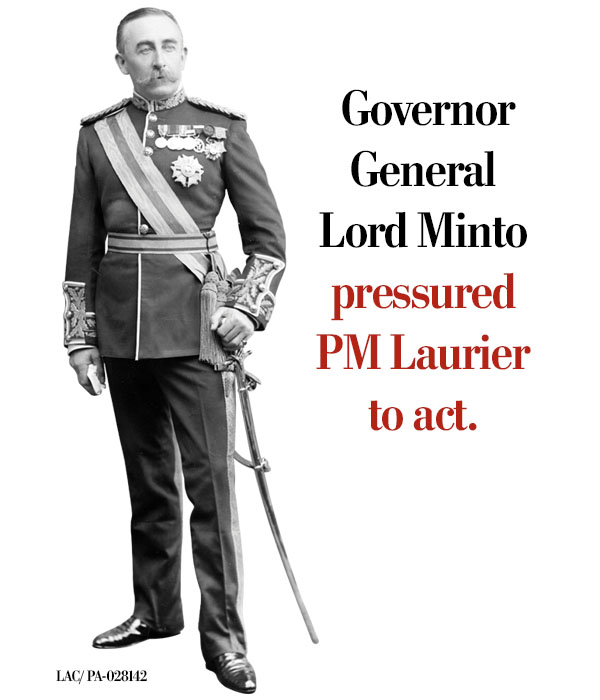

In Canada, Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier wanted nothing to do with war or the jingoistic imperialism driving it. In power for three years, Laurier believed an imperial war could fracture the delicate union between English and French Canada. But pro-war sentiment was at a fever pitch. In 1897, the dominion had lavishly celebrated Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee and most English Canadians considered themselves duty-bound to help the mother country. With action being demanded everywhere outside Quebec, Laurier’s cabinet was divided. But the intense pressure continued, aided by Canada’s General Officer Commanding, the British Major-General E.T.H. Hutton, Governor General Lord Minto, and the British Colonial Office. At the Colonial Office request, Hutton drafted plans to raise a 1,200-strong Canadian force and leaked its details to newspapers across the country. Many powerful militia officers were also apprised of the plan even as Laurier was kept in the dark. By the time he learned of it, the press and public calls for action could not be denied. A last gasp argument that the Militia Act prohibited Canadian troops serving overseas foundered on the Oct. 11 news of war’s outbreak. Conceding defeat, Laurier authorized $600,000 to raise, equip and transport a contingent to South Africa. Thereafter, Britain would be responsible for its maintenance costs.

The force was to number 1,000 with each recruit agreeing to a year’s service. There were so many volunteers that a selection process based on health, marksmanship and prior military service was instituted. Despite the war’s unpopularity within French Canada, F Company’s soldiers were all francophones from Quebec, New Brunswick and Ontario, with half its non-commissioned officers and officers also French-speaking. The battalion was organized into eight 125-man regionally based companies with one from Western Canada, three from Ontario, and two each from Quebec and the Maritimes (including the francophone conglomerate). Seventy per cent of those selected were Canadian-born and most others were from Britain. Their commander was Lieutenant-Colonel William Otter, who had distinguished himself during the Northwest Rebellion.

The 2nd RCR was inducted into the Permanent Force and sailed on Oct. 30, 1899, from Quebec City aboard the HMS Sardinian. More than 50,000 people crowded the docks to send them off.

Samuel Steele’s Strathcona’s Horse contingent—540 men and 599 horses—sailed to South Africa aboard SS Monterey. [LAC/C-000171]

Before the contingent lay an 11,000-kilometre, 30-day voyage. A converted cattle ship, Sardinian was so small people were immediately “falling over each other at every turn.” With only enough bunks for half the contingent, the rest slept in hammocks. Otter, who knew his men were woefully untrained for war and lacked any inherent cohesion, had hoped to use the time at sea for some rudimentary training. The cramped quarters, bad weather and an outbreak of dysentery scotched that idea. On Nov. 30, 1899, Sardinian docked in Cape Town. News from the front was gloomy. The Boers had seized the initiative and were besieging Ladysmith in Natal and Kimberley and Mafeking in Cape Colony.

Many of the Boers were armed with the German Mauser 7-millimetre rifle, which had a range of 1,800 metres, fired smokeless powder that hid the shooter’s position, and used a five-round clip. While the new British Lee-Enfield had a 10-cartridge magazine, each round had to be loaded singly. The rapidity of Boer rifle fire, their unexpected artillery and bold tactics utterly perplexed the British high command.

On Dec. 16, London accepted an earlier Canadian offer to provide a second contingent, consisting of mounted infantry and mounted field artillery. The first unit left Canada as the 1st Canadian Mounted Rifles, but in August 1900 would be re-designated the Royal Canadian Dragoons (RCD). This contingent was soon followed by the 2nd Canadian Mounted Rifles (CMR), and the Royal Canadian Field Artillery (RCFA). In all, the second contingent numbered 1,289 men—750 mounted infantry and 539 artillerymen.

Even as these units readied to ship out of Halifax, support for another Canadian contingent appeared, in the form of Donald Smith, The Lord Strathcona and Mount Royal. This well-known and accomplished benefactor, co-founder of the Canadian Pacific Railway and Canadian High Commissioner to the United Kingdom from 1896 to 1914, ponied up $500,000 to raise another regiment of mounted riflemen. The Strathcona’s Horse was comprised of three squadrons raised in Manitoba with a strong cadre of Mounties providing discipline to the western cowboys who flocked to its ranks (many bringing their own horses). Its commander was the legendary NWMP superintendent Sam Steele. On March 16, 1900, it embarked with 28 officers and 512 other ranks, 599 horses, 3 Maxim machine guns, 500 rounds per rifle and 50,000 rounds for each Maxim. “A more munificent offer has seldom been made by a subject to his country,” one report noted.

The need for such munificence had been painfully underscored just weeks earlier; the Boers inflicted major defeats at Stormberg, Magersfontein and Colenso between Dec. 10 and 15 (dubbed Black Week). These defeats were compounded by the disastrous Jan. 23-24 Spion Kop battle, where 8,000 Boers cut apart a 20,000-strong British force and forced its retreat. At a cost of only 67 dead and 267 wounded, the Boers killed 243 and wounded 1,250 British troops.

In Britain, Black Week caused consternation. The government decided that overwhelming force was required to defeat the Boers and a massive military buildup began that would eventually see 500,000 empire troops deployed to defeat about 88,000 Boers.

A battalion of mounted infantry and artillery, the Royal Canadian Dragoons were part of Canada’s second contingent. [Notman Studio of Halifax]

The RCR arrived two weeks before Black Week and were spared action. Instead, they spent December engaged in training and learning new fire-and-manoeuvre tactics to overcome the Boer marksmen and machine guns. The days of orderly lines battering each other with volley fire were gone forever.

On Jan. 12, the RCR marched toward Paardeberg, where General Piet Cronjé would make his fateful decision to camp east of the Modder River. The morning of Feb. 17 found Cronjé’s Boers entrenched in a crook in the river east of the drift, having had British cavalry cut off his avenue of retreat. Although the Boer line stretched about eight kilometres, the heart of the position was a wall of wagons on three sides and the river on the other. The women, children, horses and oxen were sheltered within. The British Major-General Herbert Kitchener, 1st Earl Kitchener, had 15,000 troops to confront approximately 5,000 Boers.

Canada’s first contingent fought its first battle at Paardeberg Drift on Feb. 18, 1900. [Arthur H. Hider/LAC/Acc. No. 1983-38-2]

Feb. 18 was a Sunday, and it became known as Bloody Sunday. The battle began inauspiciously when Kitchener decided to storm the Boer trenches with infantry attacking from the west, south and east under covering artillery fire. In the jumbled landscape, cohesion was quickly lost and the attack went in piecemeal. Murderous Boer fire left 1,300 men killed or wounded in exchange for about 300 Boer casualties. For the British, this marked their highest single-day loss of the war.

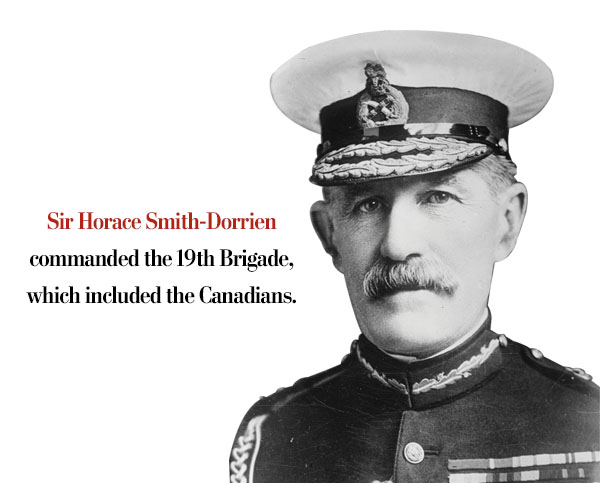

Serving as part of Brigadier Horace Smith-Dorrien’s 19th Brigade, the RCR had rout-marched 37 kilometres to reach the battlefield. Its ranks stood at 872 due to losses to disease and exhaustion. Kitchener ordered 19th Brigade to cross the Modder River and occupy a height of ground called Gun Hill, northeast of the Boers. The river was about 80 metres wide and by mid-morning Royal Engineers had strung a rope across. After wolfing down coffee, a biscuit and a rum ration, the Canadians went into chest-deep water, and by 10:15, all had gained the opposite shore. Somehow they managed to float across one machine gun on its carriage. Joining British troops on Gun Hill, they directed machine-gun fire at the Boers along the riverbank.

Now the RCR led a 19th Brigade advance against the Boer line. About 1,650 metres of open, coverless ground separated the Canadians from the Boer trenches. After 200 metres, intense fire drove the men to ground. For the next hour, soldiers advanced in small groups or alone in 20- to 30-metre dashes or by crawling. The left flank got within about 800 metres of the Boers, while the right flank closed to 400 metres before stopping dead in the face of gunfire. In the centre, the advance barely progressed. The men lay for hours under a burning sun, the slightest movement drawing fire, until mid-afternoon when a brief, drenching rainstorm added to their misery.

Soon three Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry companies, commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel William Aldworth, arrived. Telling Otter he had been sent to “finish the business” with a bayonet charge if necessary, Aldworth ordered a charge at 5:15 p.m. Many Canadians joined the Cornwalls, but the attack was met by a withering fusillade and collapsed.

With darkness, the survivors withdrew to the drift, while the Boers slipped back to their main encampment. Bloody Sunday marked the worst fighting Canadians saw during the war in South Africa—21 RCR men killed and 60 wounded. Three-quarters of the casualties occurred during the charge. For their part, the Cornwalls lost 56 men, almost all killed in the charge.

The failed frontal charges convinced the British to resort to a siege, which lasted until Feb. 26. Believing the Boers low on supplies and morale, the Canadians were ordered to conduct a night attack. Under a starlit sky at 2 a.m. on Feb. 27, with bayonets fixed, the RCR crept silently forward in two lines separated by 4.5 metres. Not a sign of life was detected in the Boer trenches until the battalion was about 100 metres away. Suddenly the Canadians were caught on open ground by murderous fire. In seconds, six men were killed and 21 wounded. Throwing themselves to the ground, the leading line steadily returned fire while those in the second line dug in. After a 15-minute gunfire exchange, a Boer shouted for the force to retire. Four of the six companies fell for the ruse and withdrew. Two companies of men from Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island weren’t duped and held firm until dawn. At 5:15, a white flag appeared over the Boer trenches. The two companies kept firing until a Boer emissary emerged at 6 o’clock and offered unconditional surrender.

About 4,000 Boers, including Cronjé, marched into captivity. The RCR had lost 13 dead and 21 wounded in the attack. But the road to Bloemfontein was open.

After the Paardeberg defeat, the Boer command avoided set-piece battles where British superiority in manpower and firepower all but ensured defeat. Instead, they formed roving commando units ranging from a few men to several thousand. Drawing on an extensive network of resupply depots and sympathetic Boer inhabitants, the commandos travelled light, hit hard and fast against static British communication networks, and melted away before the British could respond. This guerrilla warfare frustrated British efforts to capture and secure Afrikaner territory. It also required thousands of men to protect vital road and rail networks on which the British depended for supplies and reinforcement.

As mounted troops, the second contingent was ideally suited to counter the new strategy. But it meant the unit seldom served all together. This was particularly true for the RCFA, where even individual artillery batteries were broken up among various British columns chasing Boer commandos.

First assigned to “rebel chasing” was the RCD and the RCFA’s D and E batteries. From March 4 to April 14, sections of these two units trekked alongside hundreds of British soldiers over more than 1,100 kilometres of harsh terrain, from Victoria West to Upington, without engaging any Boers.

On April 10, the Strathconas landed at Cape Town. En route, 27 per cent of its horses had died from disease, mostly pneumonia. Those that lived were in poor condition. The men were scarcely better off, with 63 reporting sick within the first two weeks of deployment.

Fording the Modder River on Feb. 18, 1900, the Royal Canadian Regiment and the 1st Gordon Highlanders arrived in time to join the battle that saw Britain’s highest single-day loss of the war. Despite this, when the offensive ended on Feb. 27, it was Britain’s first decisive victory against the Boers. [/LAC/C-014923]

Meanwhile, on March 7, the RCR had joined the major British advance on Bloemfontein. On March 15, after a gruelling, sweltering march during which the men averaged 25 kilometres a day, the column entered the Orange Free State capital unopposed. A typhoid epidemic broke out shortly thereafter, killing six men. On April 20, when the regiment left Bloemfontein to clear a Boer commando unit to the city’s east, it left four officers and 150 men in hospital.

On April 25, the Canadians advanced across an open plain under protection of British artillery fire to seize the village of Thaba ’Nchu and two adjacent kopjes (small hills on flat land). Drenching Boer rifle fire killed one man, wounded two others, and stopped the line cold. While trying to organize his men, Otter suffered a bullet wound to the chin and neck that took him out of action for a month. The Battle of Israel’s Poort—as it became known—raged for three hours until the Boers withdrew. There were no further Canadian casualties.

The next day, another attack was mounted against the Boers, who had reoccupied the village to block the road to Pretoria. A confused four-day battle culminated in the Canadians and Gordon Highlanders scaling the steep face of the table-topped mountain of Thaba ’Nchu itself and clearing the Boers from this vital stronghold. Despite the ferocity of the Boer rifle and artillery fire, the Canadians lost only one man. This victory opened the way to Pretoria.

Just before the renewed advance, the illness-reduced RCR received a welcome draft of 103 volunteers. There was, however, no time to train or integrate them into the unit. On May 10, the RCR reached the Zand River, where a battle for the ford was underway. Four Canadian companies tried to seize a rise on the extreme right of the British line overlooking the river, while the remaining companies supported a brigade engaged on the left. As soon as the companies reached the rise, they came under heavy fire from about 800 Boers. Due to the small hill’s confined space, only one company could form a firing line, while a second moved into reserve, and the other two were returned to the main brigade to minimize exposure to enemy fire. Eventually an artillery section came up and broke the stalemate, scattering the Boers. Two Canadians were killed and two wounded.

On May 26, Otter resumed command and the RCR, now numbering only 443 men, crossed the Vaal River—the first British infantry battalion to enter Transvaal. Three days later, they reached Klip River and discovered Boers entrenched on Doornkop Hill. At 1:45 p.m., the RCR and other 19th Brigade battalions advanced, with the Canadians and Gordon Highlanders leading. The facing Boers set fire to the veldt and the clothes and hair of some troopers were singed as they skirted the flames. When the front line was 1,800 metres from the defensive line, inaccurate Boer artillery fire started falling. As the Canadians entered a fire-blackened stretch fronting the hill, the Boers, entrenched 1,000 metres uphill, caught them in crossfire. The Canadians took cover, but the Gordons pressed on. Just before nightfall, they charged the Boer position with bayonets. Twenty Gordons were killed and 70 wounded, but they cleared the hill, supported by the Canadians. Canadian casualties were seven wounded and no dead.

Throngs descended on Toronto’s King Street to celebrate the return of Canadian troops on June 5, 1901. [Public domain]

On June 5, the remaining 437 RCR men entered Pretoria to find it undefended. After Pretoria, the RCR took up garrison duty at various railroad stations until the regiment’s tour ended. On Oct. 1, 11 months after arriving in Cape Town, the RCR departed for Canada.

The RCR wasn’t the only Canadian regiment to participate in the march to Pretoria. In a separate column, three CMR squadrons and the RCD rode in the 1st Mounted Infantry Brigade. Their 33-day march took a different route from that of the RCR column. They fought several sharp actions, particularly at Coetzee’s Drift on May 5, participated in the Zand River and Doornkop battles, and entered Pretoria on June 6. Remarkably, during these engagements only two Canadians were wounded.

While the RCR and mounted infantry regiments marched to Pretoria, RCFA batteries joined in the relief of Mafeking. The British plan was to advance on Mafeking from both north and south. To the north, only one British regiment existed, the 800-strong Rhodesian Regiment, which was too weak to challenge the Boers. Therefore C Battery RCFA sailed as reinforcement, along with the 5,000-strong Rhodesian Field Force, to Beira in Portuguese East Africa. From there, an arduous 1,600-kilometre journey, partially by train and the rest at the march, brought the column to Mafeking from the north. On May 15, the Field Force married with a column approaching from the south at Jan Massibi and encountered the Boer siege force at about noon on May 16.

The Canadian battery engaged in a three-hour artillery duel with Boer gunners at Sanie Station. The fire succeeded in clearing the road and at 4 a.m. on May 17, forward elements entered Mafeking to a warm welcome from the weary defenders. C Battery remained in northwestern Transvaal until returning to Cape Town on Nov. 20 for a Dec. 13 sailing to Canada. During this time, it slogged from one small engagement to another, chasing elusive Boer commandos that occupied towns and destroyed rail tracks with near impunity. In other parts of South Africa and the Afrikaner states, the same unrewarding task fell to the other Canadian artillery units.

Boer rebel leader, general and politician Christiaan de Wet evaded British capture right to the end of the war. [Alamy/BGCY99]

Eventually, both Canadian mounted regiments moved to northeastern Transvaal and were dragooned into Kitchener’s scorched-earth strategy, intended to deny the commandos succour and support by burning farms and imprisoning the civilian Boer populace. On Nov. 6, a column commanded by Smith-Dorrien set out to break up Boer commando units in the Carolina area. The CMR, RCD and D Battery participated. After a series of skirmishes that failed to quell the Boers, Smith-Dorrien decided at Leliefontein to withdraw and return to Belfast. The rearguard fell to the RCD.

As the withdrawal began, two commando units, numbering about 200 men, attacked on Nov. 7. The RCD, supported by D Battery’s two guns, held off the Boers while conducting an orderly withdrawal. As the Boers pressed harder, it seemed likely the guns would be captured. Only a hasty ambush sprung by Lieutenant Richard Turner and 12 men prevented Boer success. The entire action cost the RCD three dead and 11 wounded. Turner and two other men—Lieutenant Hampden Zane Churchill Cockburn and Sergeant Edward James Gibson Holland—were awarded Victoria Crosses. Leliefontein was the second contingent’s last major action. Most of its soldiers returned to Halifax on Jan. 8, 1901.

The Strathconas were also assigned to Kitchener’s scorched-earth policy as part of the Natal Field Force. On Sept. 1, 1900, the Strathconas marched with Buller toward Lydenburg in pursuit of a 2,000-strong commando unit. A sporadic running battle ensued, with the Boers withdrawing and the Natal Field Force trying to block the retreat. After a month, the chase was abandoned and in mid-October, the Natal Field Force was broken up. The Strathconas prepared to return to Canada.

However, a sudden rekindling of Boer action under General Christiaan de Wet surprised the British, and Kitchener redrafted the Strathconas on Oct. 24. Three days later, Steele and his tired, increasingly dispirited force returned to action. The Strathconas marched and counter-marched across the Orange Free State and Transvaal districts. Although several battles were fought, de Wet eluded capture and the pursuit was abandoned on Jan. 9, 1901. By month’s end, the Strathconas sailed home. Twenty-three had died in South Africa.

This concluded the Canadian military contribution to the Second Boer War. In all, approximately 280 of the 7,368 Canadians who served in South Africa died there. More died from disease and injuries than combat wounds.

On May 31, 1902, the Boers accepted the loss of their independence in a peace agreement with Britain. For Canada, the South African contingents established an important precedent because most remained distinct units commanded by Canadian officers. But for many of the Canadians, the war had been a bitter experience. Even Otter described it as “blood and sand and everything that is disagreeable all for a bit of riband [ribbon] and a piece of silver.”

Top photo: The ill-fated Jameson Raid of 1895, led by British colonial politician Leander Starr Jameson, was one of many antagonizing events that led to the Second Boer War, from 1899 to 1902.

Advertisement