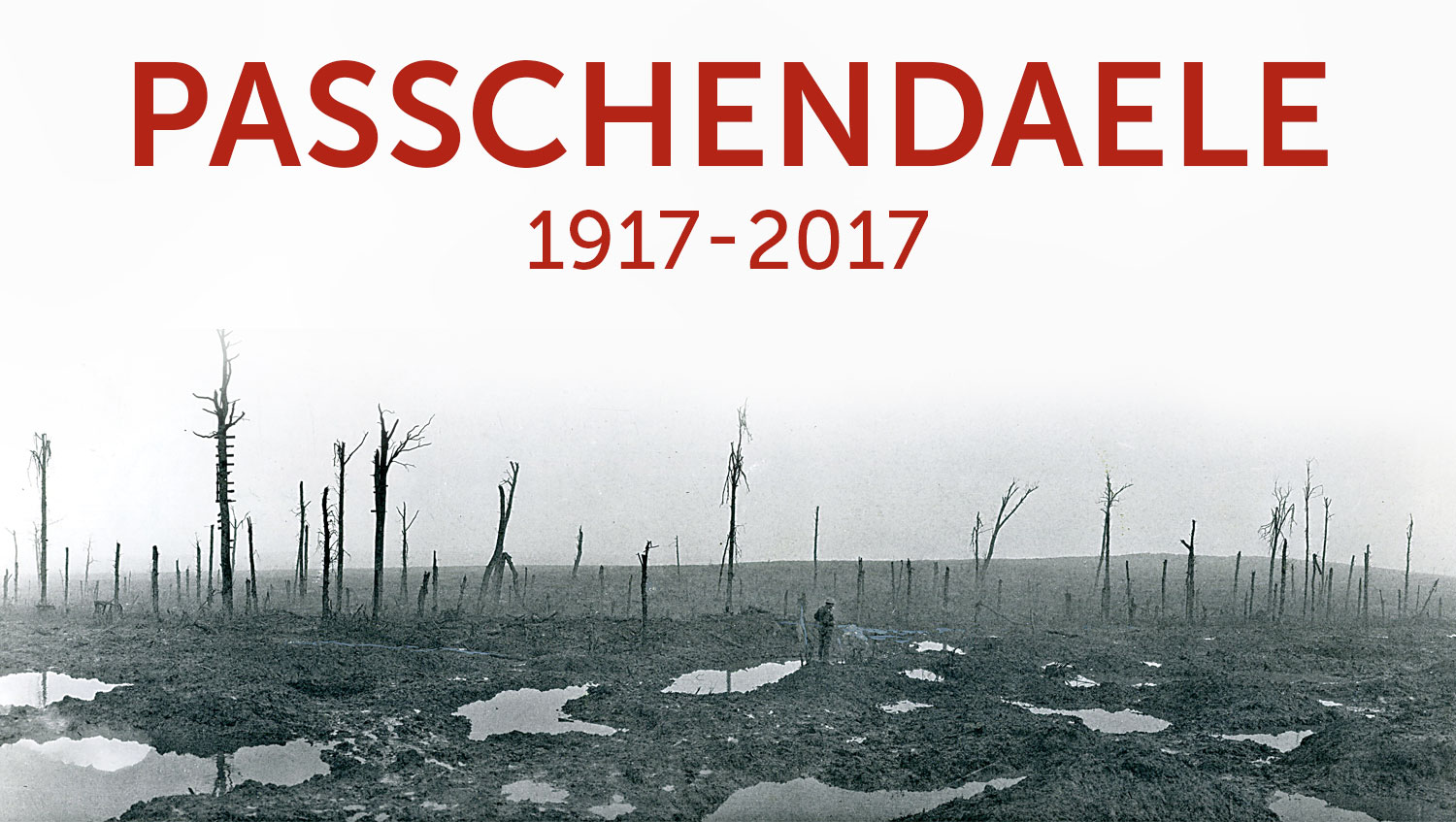

Passchendaele is a lovely name—whether in Flemish or French, it rolls lyrically off the tongue, conjuring images of a sylvan glade, lush with greenery and sprinkled with wildflowers. Or that’s how it should be. Instead, a misfortune of geography turned Passchendaele into a synonym for pointless slaughter.

During the First World War, it became a gigantic cesspool where dreams, plans and reputations went to drown. The ultimate objective of the ill-considered Third Battle of Ypres, it was a feature of dubious tactical value that was contested as if it held the key to victory. As the winter of 1917 closed in on Flanders, the Canadian Corps was called on to capture Passchendaele and the high ground behind it, and bring the agony to an end.

By the middle of 1917, the leaders of Britain and France had conceded that they couldn’t win the war that year. Instead, using limited operations to wear down the enemy, they would prepare for a final offensive to be mounted in 1918, once the Americans were in the field in numbers.

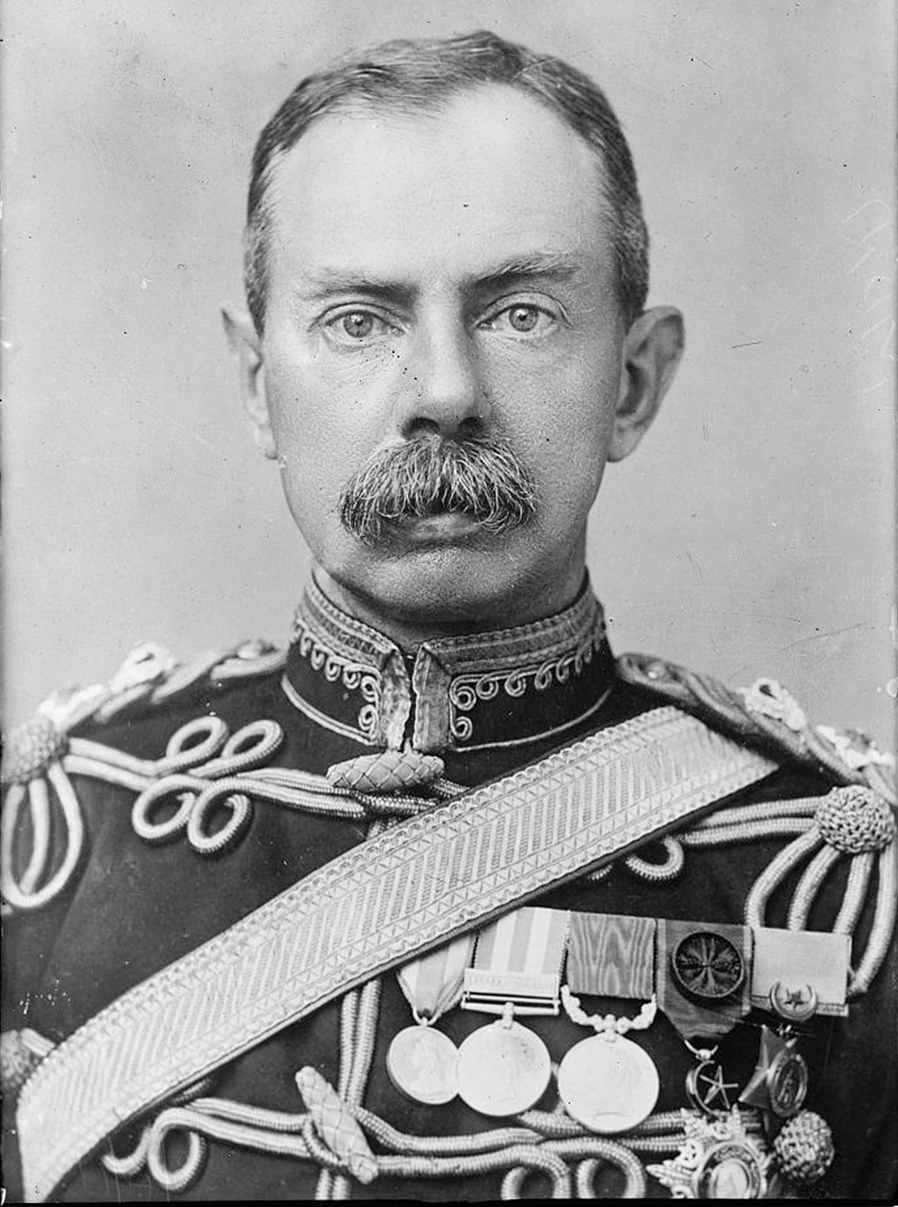

Douglas Haig, the British Army’s commander in France, had other ideas. He didn’t want to wait for the Americans; he wanted to fight the decisive action before they could rush in and claim the victory. Backed by the Royal Navy’s apocalyptic (yet disingenuous) prediction that unless the Belgian ports on the English Channel were denied to German U-boats, the war would be lost before 1918, he planned a master stroke near Ypres that would retake Zeebrugge and Ostende. Then, his cavalry could take to the field and liberate Belgium from the west.

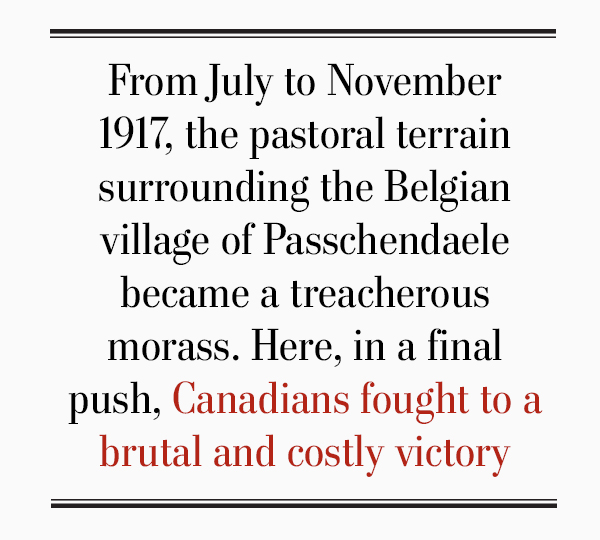

The opening act was an attack on Messines Ridge, south of Ypres, orchestrated by the British Second Army under Field Marshal Herbert “Daddy” Plumer. With his florid complexion and walrus moustache, Plumer looked exactly like the kind of wheezing, claret-soaked general that soldier and poet Siegfried Sassoon lampooned so viciously, but looks were deceiving. Plumer was one of the best British generals of the war—painstaking in preparation and utterly unflappable. At Messines, he mounted a classic “bite-and-hold” operation—launch an attack on a limited objective that had been softened up by vast quantities of explosives, and then invite the enemy to incur ruinous casualties trying to win back the ground. Plumer’s plan used mining to its fullest advantage, driving ammonal-filled galleries far under German lines. When they were detonated on June 7, the top of the ridge effectively ceased to exist—as did most of its defenders. The survivors, harried by a devastating artillery barrage, were too stunned to offer much resistance, and the remains of the ridge passed into British hands.

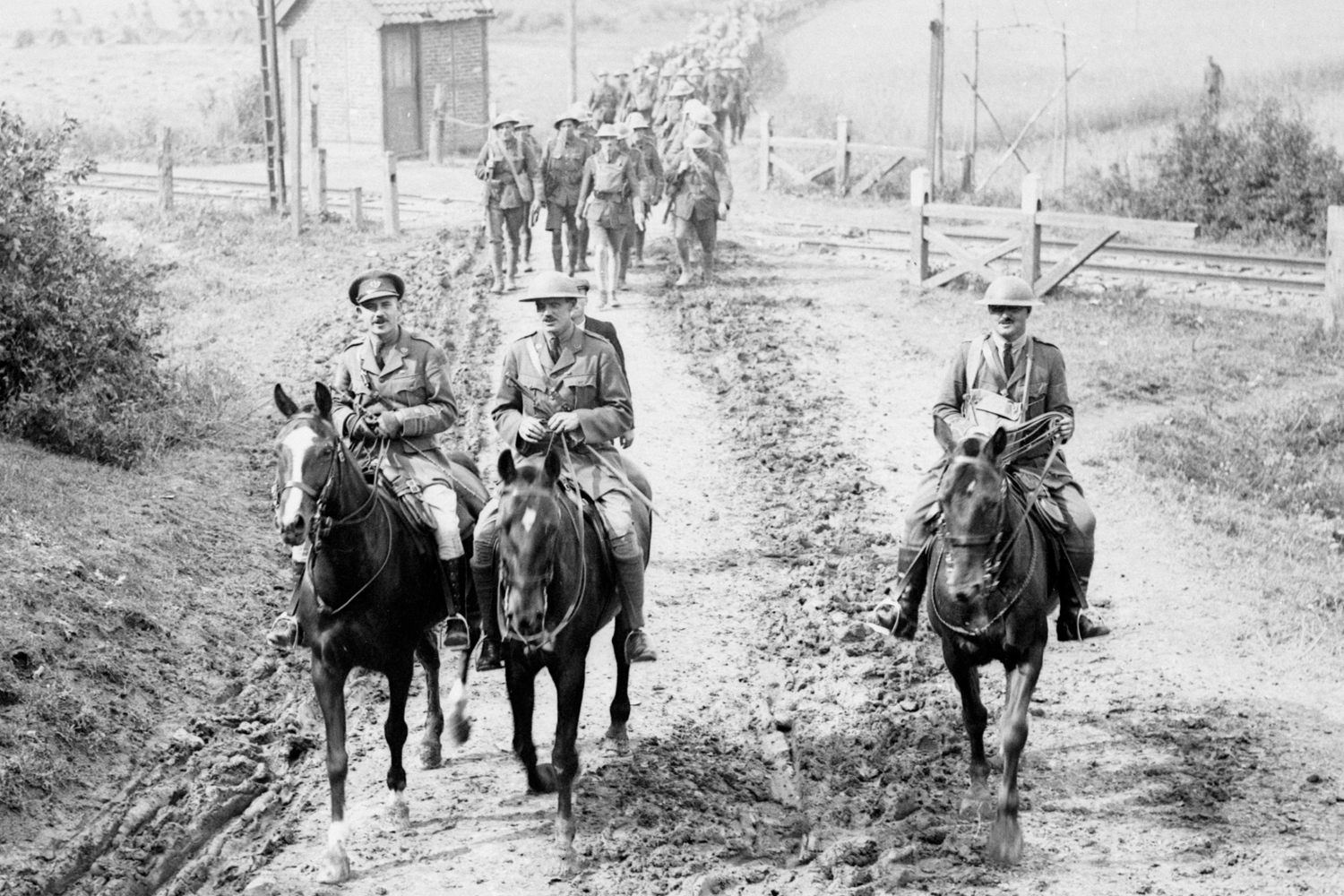

Unflappable at Passchendaele, the Canadian Corps served under Field Marshal Herbert Plumer, commander of Britain’s Second Army. [Wikimedia]

The victory at Messines seemed like a vindication. For Haig, it proved that a great offensive in Belgium should proceed sooner rather than later, to exploit the success. For the British War Cabinet, never so enthusiastic about Haig’s grand plans, it proved that small attacks with strictly limited goals were far superior to a big push. But the politicians didn’t relish a fight with Haig and grudgingly allowed him to go ahead with his plans. Perhaps they were hoping he had learned the dangers of massive open-ended operations. If so, they should have been alarmed by his change of direction. In the vanguard, Second Army under Plumer, who had proven his “bite-and-hold” approach, was replaced by Fifth Army under Hubert Gough, an old cavalry thruster with an “advance at all costs” mentality.

From the beginning, the costs far outstripped the advances. The offensive opened on July 31 and after the first four days, Fifth Army found itself a few thousand metres in the black—and more than 31,000 casualties in the red. Haig reported these results to be “highly satisfactory.” A second push in mid-August achieved little and by then the offensive had fallen victim to something Haig and his staff had been inexplicably reluctant to account for: the weather.

Master planner Field Marshal Douglas Haig, Britain’s commander in France, failed to account for the weather. [Legion Magazine archives]

Flanders is a very low-lying region with a high water table, in some places just a metre or two below the surface. Generations of Belgian farmers had learned to cope with the topography, using complex networks of dikes and drainage ditches to keep their fields dry. But three years of fighting had all but destroyed the natural and man-made drainage systems. Flanders was fine when it was dry; but when it rained, the water just sat on the surface, turning fields into morasses. On the second day of the offensive, it started to rain.

That August was the wettest in years, and the deterioration of the battlefield forced Haig to change plans. A big push was no longer realistic given the state of the ground, and a reverse in the north had rendered his coastal advance out of the question. So, the campaign would become part of his wearing-down strategy of weakening the enemy until he could no longer resist. Haig turned to smaller attacks with limited objectives, giving the lead back to Plumer and Second Army. It was a sound decision, but an unfortunate byproduct was that it required a massive reorganization of the front—while three weeks of good, dry campaigning weather were lost.

When the offensive was remounted on Sept. 20, the rains had returned. Still, Plumer was optimistic about his plan, which involved a massive concentration of infantry and artillery on a narrow frontage against an objective only 1,400 metres ahead. It was completely successful, as were attacks on Polygon Wood on Sept. 26 and Broodseinde on Oct. 4. Still, there was no avoiding the hard truth: most of the Day 1 objectives remained in enemy hands, more than two months in.

Critics still maintain that play should have been called on account of rain. But Haig’s attritional strategy had become more focused and he now gave three specific reasons for continuing: to support an imminent French attack in Champagne; to keep the enemy busy while the Cambrai offensive was gearing up; and to secure better winter lines atop Passchendaele Ridge. There would be a pause to improve transportation networks, and in hopes that the rain might stop, but the campaign would go on.

Long walk: Canadian and German wounded help one another through the mud during the Battle of Passchendaele. [DND/LAC/PA-003737]

Haig was enough of a realist to know that the offensive couldn’t be pushed without fresh troops, and his attention had already focused on the Canadian Corps. General Arthur Currie, Corps commander since June 1917, was not overjoyed at the prospect of entering a campaign that had so little to recommend it, but at least he was satisfied with the chain of command. He made no secret of his reluctance to put the Corps under Gough, but he was quite amenable to Plumer, with whom he had much in common. The 3rd and 4th Canadian divisions moved into position on Oct. 18, relieving the II ANZAC Corps.

The road to the front would have caused anyone to abandon hope. One battalion war diarist reported that thousands of “dead horses and mules are to be seen in the four-mile stretch to the firing line; large numbers of human bodies, which have been hurled from their graves by the bursting of large shells add a very poignant note to the horror of the general surroundings.”

Nova Scotian Frank Iriam, who had marched up the same road with the 8th Battalion in April 1915, recalled that the “single track line of road across the sea of mud was a shambles, a slaughterhouse and a good example of Hell or Hades in full blast.”

The Canadian sector had two pieces of higher ground. Just left of centre, a low spur stretched southwest toward Ypres, culminating in the hamlet of Bellevue. On the right was the main Passchendaele-Wytschaete ridge line. Between them was a true no man’s land: the valley of the Ravebeek River. The banks of this stream had long since disappeared, turning the entire area into an impassable swamp hundreds of metres wide in places. Nearly half of the Canadian sector, then, was too wet to use—and the other half was clogged with the ejecta of battle that the Australians had been unable to clear. That was Currie’s first order of business. The other essential tasks were to haul out for repair dozens of unserviceable artillery pieces and to construct proper gun pits. If Currie was determined to expend shells rather than lives, the gunners had to be able to ply their trade.

To the front Officers lead the 8th Battalion into the line at Passchendaele in October 1917. The 7th and 8th battalions captured Vindictive Crossroads, north of the village, on Nov. 6. [DND/LAC/PA-0020635]

The first Canadian attack was the initial jump in the leapfrog toward the village of Passchendaele. It was supported by more than 400 artillery pieces of all calibres from Canadian, British and New Zealand batteries; they stood ready in gun pits laboriously built by work parties from supporting units. For those infantrymen-cum-pioneers, the labour had seemed never-ending. The war diary of the 75th Battalion reported that “Men begin to show signs of fatigue, but carry on cheerfully…. Mud everywhere, never imagined there was so much mud in the world.”

J.H. Becker of the 75th would have agreed. Squatting in a shell hole, knee-deep in water, he and a pal waited, for what they weren’t sure: “The rain came down in torrents and as we sat there with our backs against the earth towards the Germans, listening to the whine and crash of shells all around us, we were about as miserable a pair as one could imagine…. We had no idea where we were, who was in the front line ahead of us or where that line was. All we could do was sit there and wonder—wonder many things.”

Just before 6 a.m. on Oct. 26, in a thick mist that would soon turn to rain, the lead battalions moved out. In the trenches at the extreme left of the Canadian front, Lieutenant Ray Warne of the 4th Canadian Mounted Rifles waited for the attack. His troops “were nearly frozen, soaked to the skin and the rain coming down in torrents…. At last [the barrage] lifted and away we went. It was a sight one could never forget. Men dropped all along the line, but the rest struggled through the mud towards the ‘pill boxes’…where the machine guns spat a continuous stream of death…. It was terrible to see the wounded holding out their arms begging for help and yet be unable to help them.”

With the 43rd and 58th battalions to the right, the mounted riflemen inched toward their objective under punishing German fire. Most eventually got where they were headed, only to be pushed back by fire from their flanks. There was a single exception: a small party of the 43rd Battalion, clinging to the southern tip of the Bellevue spur. They held on for vital hours while another attack could be organized, and by mid-afternoon, the 52nd Battalion had regained the intermediate line. The following morning, lead units were within a few hundred metres of their final objectives.

Staff support: General Arthur Currie is surrounded by his officers at Passchendaele in November 1917. Currie demanded that the Canadian Corps serve in Plumer’s British Second Army. [DND/LAC/PA-002150]

In the meantime, confusion had overtaken the operation south of the Ravebeek. Decline Copse straddled the boundary between the Canadian and Australian sectors, a vulnerable spot in any operation. The 46th Battalion had captured it, but miscommunication with the relieving unit allowed the Germans to reoccupy parts of their original line. For hours, the two sides scrapped and clawed over the shattered wood; not until the following evening were the last of the Bavarians ejected from Decline Copse. One day of attacking had been followed by three days of fending off German counter-attacks, but finally the lines were firmed up.

On the 30th, the second Canadian attack went ahead to seize what would become the start line for the attack on Passchendaele village itself. It was a clear but cold and windy day that turned, to no one’s surprise, rainy in the afternoon. Official documents noted that the advance went smoothly; with the sang-froid that only a battalion war diarist could manage, the 78th’s reported that “the whole Brigade advanced under cover of the barrage like men on parade.”

In fact, the barrage was indifferent in places, and the 78th and 85th battalions’ advance was quite unlike a parade, wilting and then stalling under heavy enemy fire. But the check was only temporary. The senior surviving officer of the 85th called up the reserve company and, with the injection of new energy, the assault began to move forward again, hugging the mud and bringing heavy small-arms fire down on enemy positions. The same thing happened to the 78th—a momentary check, a decisive intervention by a surviving officer, and a second effort that carried the objective. Both battalions were consolidating their newly won positions within 90 minutes of zero hour.

Success for the men of the 72nd Battalion seemed even more unlikely. Ahead of them was the heavily defended Crest Farm, so well protected that there was only a narrow gap

for the attacking companies to get through. A betting person might have wagered against them, but they moved with surprising speed over the swampy ground, benefiting from a flawless artillery barrage. Their capture of Crest Farm impressed even Haig, and one can forgive the celebratory tone of the war diary: “The Huns ran in all directions and it is a certainty that they were completely demoralised.”

Sheltering: Wounded Canadians take cover behind a damaged pillbox at Passchendaele. [DND/LAC/PA-002139]

To the north, the tactical outlook was bleak. The attacking units—Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, the 49th Battalion and the 5th Battalion, Canadian Mounted Rifles—would be advancing uphill and the artillery support was even spottier, with too many shells falling short and too many enemy positions left unmolested. The Patricias sustained ruinous casualties taking the fortified hamlet of Meetcheele, while the 49th lost even more men getting as far as Furst Farm. On the far left, the 5th CMRs struggled mightily to reach their objectives, only to find that the units on either side were nowhere to be seen.

Major George Pearkes was in command of a small band of survivors occupying Vapour Farm. Having advanced deeper into enemy territory than any unit in the division, they were not disposed to give it up. Pearkes’ messages, sent back over the course of a trying day, betray the danger of his situation. At 7:45 a.m., he reported “Have about 50 men from ‘C’ and ‘D’ [companies]. We must have help from both sides. Hun about 200 yards away. Am digging in.” By 1 p.m., the situation had deteriorated: “Both my flanks in the air. Bde. on left must endeavour to come up. Am short S.A.A. [small arms ammunition] but will hang on.” At 2:45 p.m., the strain was beginning to tell: “All very much exhausted. Ammunition running short. Do not think we can hold on much longer without being relieved.” Three hours later he repeated, “Do not think I can hold out until morning.” But hang on they did, until they were relieved at dusk. Pearkes, his pant leg stained with blood from a shrapnel wound he had ignored for hours, was later awarded the Victoria Cross.

War hero: Major George Pearkes, VC, photographed in December 1917. He was wounded five times over the course of the war. [PA-002364]

With that attack, a thousand-metre advance that cost more than 2,300 casualties, the 3rd and 4th divisions had finished their work at Passchendaele; they were pulled back to reserve lines and the 1st and 2nd divisions took their places.

Ahead was a two-step operation. The first stage, set for Nov. 6, would capture the remains of Passchendaele village; the second stage would secure the ridge behind the village.

It would be the Canadians’ toughest test. Although the infantrymen were gradually moving onto higher and drier ground, it was ground that was now little more than a mosaic of overlapping shell holes filled with a ghastly soup of rainwater, chemicals and human remains.

“Here on the battlefield things are horrible,” wrote Napoléon Gagné to his wife in Pointe-Gatineau, Que., on Nov. 6. “What you see in the newspapers is nothing to what we see here on the battlefield. We are human beings who have lost their spirit…. I am getting so tired of this miserable state. It rains all the time and winter is coming.”

Stretcher-bearers: Canadians carry a wounded German prisoner around a water-filled shell hole. [PA-040138]

The artillery’s positions were gun pits in name only, the guns being driven deeper into the mud with every round. The gunners worked without shelter, counting on the ooze around them to smother nearby blasts, but it was corrosive on the nerves.

“Raining all day,” wrote New Brunswicker Harry Mollins of the 2nd Canadian Siege Battery in his diary. “The mud is something fierce. All the shell holes are full of water. I am wet thru & coated with mud. Am disgusted with everything.”

The situation was scarcely better for the men who had to manhandle supplies up to the front. Ceaseless work on the roads kept them passable, but only just. Howard Stevens, a young officer with the 107th Pioneer Battalion, described the scene in a letter to his family that was published in his local newspaper in Bracebridge, Ont.: “The mud was the worst I had ever experienced. Horses would mire in shell holes and could not be taken out, and had to be shot. Have seen dozens of horses and men lying along the road, just where they had fallen, killed by high explosives or overhead shrapnel. They were pulled to one side clear of the roads and left. No time to bury them, because the ammunition had to go forward to the guns.”

Billets: Battle-weary Canadians rest in a shell-shattered house following the fight for Passchendaele. [DND/LAC/PA-003694]

At 6 a.m. on Nov. 6, the barrage opened and the lead units plunged ahead on what Frank Iriam called a “half-swimming, half-crawling and wholly miserable advance across that morass in cold drizzle of winter rain.” Despite the unforgiving terrain, they moved surprisingly quickly, and stayed so close to the barrage that they were occasionally right inside it. Working methodically from shell hole to shell hole, riflemen from five battalions moved inexorably toward Passchendaele, using bayonets as freely as bullets and bombs. Within three hours of zero hour, the village had been taken and supporting battalions were moving north toward the ridge. They had a long day ahead as the Germans tried to pry them from the ruins, but they wouldn’t be dislodged. At a cost of more than 2,200 casualties, including 734 killed, Passchendaele and its environs were firmly in Canadian hands.

The last mission—to capture the high ground north of Passchendaele, including the highest point on the ridge and the aptly named Vindictive Crossroads—took place on Nov. 10 on the narrowest front yet. The heavy lifting would fall to two battalions, the 7th and 8th, whose front quickly became even narrower. At 6 a.m., in the usual heavy rain, the lead battalions left the start line and made good progress; before too long, one company of the 8th was reported to be “on its objective and apparently quite happy with the situation.”

On the left wing, however, the British attack had sputtered and then died, forcing the 8th Battalion to defend its flank while the 10th Battalion came up to help hold the new front line. With the Canadian front narrowed by almost a third, German artillery—five corps’ worth—could concentrate its fire. They were bombarding trenches they had recently held, so their ranging was perfect, while Canadian counter-battery fire was hampered by poor visibility.

Hour after hour, shells rained down on the Canadians as their numbers were slowly whittled down. The rain and mud began to take a toll on their rifles, many of which became unserviceable. But they held on, grimly, doggedly, and eventually were able to consolidate their gains. The wounded staggered and stumbled to regimental aid posts—an officer of the 10th Battalion described the men who made it back as “pitiable.” They were the lucky ones, for so many men never emerged. The 8th Battalion’s war diarist reported that two men drowned trying to get back across the Ravebeek, “not having the strength to cross the little stream.”

After that last battle, the diarist of the 10th Battalion observed wryly, “the Unit had no opportunity to execute any brilliant moves.” The comment could apply to the Canadian Corps as a whole at Passchendaele. It was not a campaign that saw much tactical brilliance, for the conditions scarcely permitted it. Instead, it was marked by dogged determination, painstaking preparation, the overwhelming weight of artillery, and countless acts of remarkable personal gallantry. Some battles are about artistry and brilliance; Passchendaele was about sheer hard work and apparently superhuman endurance.

Casualty: A wounded Canadian is carried to an aid post. The Corps suffered 15,654 casualties at Passchendaele. [PA-002107]

Historians will long dissect the 103-day campaign—what it achieved, and if it was worth the cost. Currie and the Canadian Corps didn’t have the luxury of debating whether the offensive should be pressed; they were given a task, and that was that. Currie could tinker with plans and dates, and thereby tilt the scales in his men’s favour, but he couldn’t decline the order. When first presented with the problem of taking Passchendaele, the general predicted it would cost the Corps 16,000 casualties. At the final accounting, he was within a few hundred of that prediction.

A century on, Passchendaele has reverted to what its name suggests—verdant copses, rich farm fields, a landscape of peace and order. Every spring, there is the annual harvest of iron, when farmers comb from their fields the detritus of war that has come to the surface over the winter. Viewed from above, the ghostly outlines of trenches and craters are still visible on the landscape, and German pillboxes can be seen in Tyne Cot Cemetery. At Crest Farm, a mute block of Canadian granite holds an epitaph that seems so fitting because it is so terse: “The Canadian Corps in Oct.-Nov. 1917 advanced across this valley—then a treacherous morass—captured and held the Passchendaele Ridge.”

Top photo: Silent sentinels – The war-ravaged battlefield near Passchendaele, Belgium, in 1917. [LAC/PA-040139]

Advertisement