Lance-Corporal W.J. Chrysler helps Pte. Morris J. Piche to an aid station during April 1951 fighting between Canadian and Chinese forces in Korea’s Kapyong Valley.[Canadian Army/IWM/MH33026]

And, so, when a U.S.-led United Nations coalition stepped in on the Korean peninsula, President Harry S. Truman and Prime Minister Louis St-Laurent called it a “police action,” an “intervention.”

The terms didn’t sit well with those who were there.

“There were 516 [Canadian] military guys dead over there,” Georges Guertin, a radio operator aboard HMCS Huron at the time, told Legion Magazine in a recent interview. “I don’t call that a ‘police action.’ Just an ugly little war.”

In fact, no war was ever declared, and for the next 40 years or so the happenings of 1950-53 on the Korean peninsula were officially referred to as “the Korean Conflict.” There was a Cold War, all right, but God forbid another hot one.

To most all but those who fought it, Korea was “The Forgotten War.”

In Canada, the combatants were not formally recognized as war veterans until the late-1980s, when Ottawa decided the war was, in fact, a war. And it was not until 1991 that veterans were awarded Canadian medals for their service in Korea.

That same year in the U.S., which provided the bulk of resources to the war effort, President Bill Clinton signed Public Law 105-261, Section 1067 of which declared the “Korean Conflict” would henceforth be called the “Korean War.”

Semantics? No. The change had ripple effects throughout the coalition of countries that made up the UN force in Korea. It influenced such things as pensions and compensation for veterans, including the 26,800 Canadians who served.

Groups such as the Korea Veterans Association of Canada, which wasn’t formed until the 1980s, stepped up efforts to get vets the support they needed—and deserved. With numbers dwindling, the group folded two years ago and was replaced by the more centralized and descriptive Korean War Veterans Association of Canada.

The recognition deeply affected many who had long felt their service had been taken for granted if it had been recognized at all. While Vietnam War veterans would return to America to a hostile anti-war welcome in the 1960s and early ’70s, Korean War veterans of the 1950s got no public reception whatsoever.

Korea vets endured passive hostility in the form of veterans’ organizations that refused to recognize their service, resisted incorporating the Korean War on cenotaphs and generally belittled their contributions, all while overlooking the fact that about 16 per cent of all those who served in Korea also served in the Second World War. They knew what war was.

Acquired from U.S. Army stocks, the Sherman tank Catherine of B Squadron, Lord Strathcona’s Horse (Royal Canadians), leads a column along Korea’s Imjin River on July 16, 1952.[LAC/PA-115496]

Some 2.5 million Koreans died, were wounded or disappeared during the course of the three-year war, while 10 million families—a third of the population—were separated.

Despite the shift at home, the recognition afforded Korean War veterans by Canadians pales in comparison to the gratitude and gestures of the people and government of South Korea, which has awarded them medals, hosted pilgrimages and thrown annual parties in their honour.

South Korean representatives are unfailing in placing wreaths at the National War Memorial in Ottawa to mark Remembrance Day and anniversaries associated with the war and armistice. Visiting South Korean presidents take the time to pay their respects by placing wreaths no matter the season. President Yoon Suk Yeol did so in September 2022.

Some 2.5 million Koreans died, were wounded or disappeared during the course of the three-year war, while 10 million families—a third of the population—were separated. Industry and infrastructure were gutted on both sides.

By war’s end, Seoul had been taken and retaken four times. The sprawling city was left a ruin.

South Korea had lost 17,000 businesses, factories and plants, 4,000 schools and 600,000 homes. The gross national product had declined 14 per cent and total property damage was estimated at US$2 billion.

Its air force virtually erased, the North bore the brunt of the fighting after September 1950. The United States Air Force dropped more than 350,000 tonnes of conventional bombs and almost 30,000 tonnes of napalm on North Korean cities and fired 313,600 rockets and 167 million machine-gun rounds.

The North Korean leader, Kim Il Sung, said the country’s economy had been destroyed. It had lost 8,700 industrial plants, 367,000 hectares of farmland, 600,000 houses, 5,000 schools, 1,000 hospitals and 260 theatres.

Historian James Hoare reported that the North’s national income in 1953 was 69.4 per cent that of 1950; electricity production was reduced to 17.2 per cent of 1949 levels, while coal was down to 17.7.

“There had been a huge loss of able-bodied men either killed or who fled South,” wrote Hoare. “Effectively, therefore, apart from the end of the fighting, both sides found themselves in the summer of 1953 with nothing to mark and nothing to celebrate.”

Some “conflict.”

Yet, for South Korea at least, the end of the war would mark the gradual beginning of a new age. The country would rebuild and far surpass anything it had known or could have expected before in terms of development and prosperity. It is now a cultural phenom, a tech giant, and Seoul a sparkling jewel of southeast Asia.

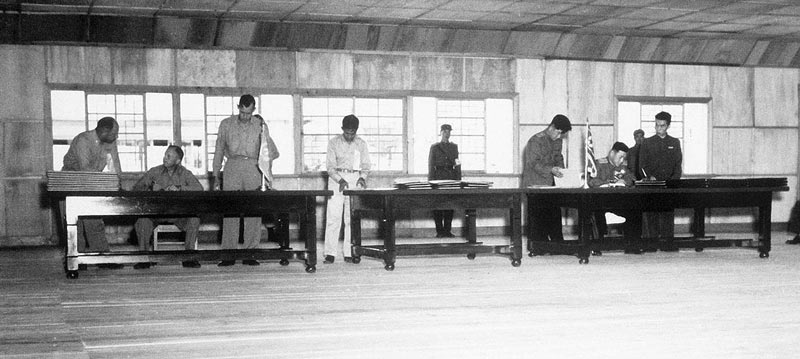

North Korean leader Kim Il Sung signs the Korean Armistice Agreement in July 1953. South Korean President Syngman Rhee refused to sign, insisting he wanted to continue fighting for a united Korea.[Wikimedia]

They may not have left behind a united Korea, but their war gave the South the freedom and, ultimately, the means to prosper.

“The country went from a war-torn, impoverished nation to a global industrial powerhouse in just two generations,” wrote Chung Min Lee in a November 2022 essay for the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

“Before this turn of events, no one could have imagined that South Korean actors would win an Oscar and an Emmy or that K-pop would reach a global audience.

“A country that relied on U.S. aid until the 1960s is now investing tens of billions of dollars to build new electric vehicles, next-generation batteries, and semiconductors in the United States.”

While South Korea has its problems, too, it is in its triumphs that the veterans of the Korean War take pride. They may not have left behind a united Korea, but their war gave the South the freedom and, ultimately, the means to prosper.

In a Dec. 1, 1953, telegram to the U.S. State Department, Arthur H. Dean, special United States envoy to the post-armistice political conference, effectively laid the blame for the impending failure to reach a peace at the feet of South Korea’s president at the time, Syngman Rhee, who had refused to sign the hard-earned armistice and wanted to continue fighting.

“Rhee is presently very querulous,” wrote Dean. “Thinks he was tricked into armistice. Now thinks defense pact and economic program are dishonorable bribes to him not to unify Korea by force.

“He sees his lifetime dream of a unified Korea rapidly fading.”

Dean said he had the “distinct impression Rhee now feels free world does not deserve a fighting Korea, that rest of us have lost our courage to fight Communism and he would be glad to see us go.”

“He recites in detail every bit of concession we made to get armistice and in working out demilitarized zone and he is convinced, if we do not fight, [a peace conference] will merely result in yielding up one concession after another by our side to final surrender all Korea. Any constructive suggestions by us are, of course, outright concessions to Communists in [South Korean] view.”

And, so, the North of Kim Jong-Un remains a hostile neighbour—a hoarder of nuclear weapons, a source of regional instability and a continuing threat to world peace.

It has conducted multiple missile tests and at least six times announced it will no longer abide by the armistice. It has violated its terms dozens of times, including military attacks. Both sides conduct provocative military exercises.

In December 2022, five North Korean drones crossed the demilitarized zone into South Korea. South Korea scrambled helicopters and fighters to intercept them. A South Korean helicopter fired on one of the drones, but none are known to have been taken down. A UN investigation concluded both sides violated the armistice.

American Lieutenant-General William K. Harrison, Jr. representing United Nations forces (seated left), and General Nam Il, representing the Korean People’s Army and Chinese People’s Volunteers (seated right), sign the Korean War armistice agreement at P’anmunjŏm, Korea, on July 27, 1953.[Kazukaitis/US Navy/DoD/Wikimedia]

“The Korean War armistice wasn’t meant to last forever, but an end-of-war declaration, let alone unification, looks less and less likely every year,” wrote analyst James Fretwell.

“And that may be the key lesson to draw from the Korean War precedent: While ending active hostilities, the armistice laid out no clear path for a formal peace or unification. The result has been undying division—whether anyone wants it or not.”

—

See the latest edition of Canada’s Ultimate Story, Korea: The war without end, available on newsstands and online in the Legion Magazine shop.

Advertisement