Weasel words, workarounds and loopholes: the first arms control treaty was short-lived

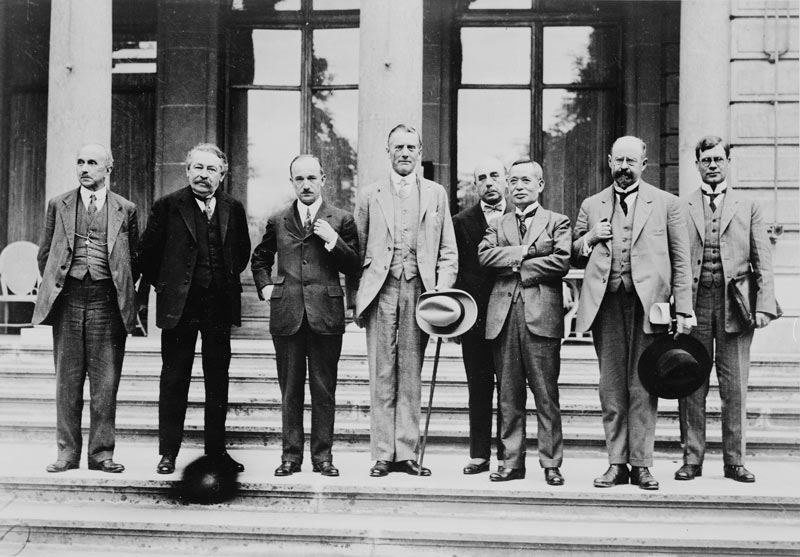

In November 1921, back when Britannia still ruled the waves, representatives of five war-weary allied nations got together in Washington, D.C., and negotiated an agreement aimed at preventing an arms race at sea.

The Washington Naval Treaty, also known as the Five-Power Treaty, didn’t last. Twelve years after it was signed in February 1922, the deal to limit the production and size of warships began to crumble. By 1936, it was dead in the water.

The first significant arms control agreement of the 20th century, a time that would be marked by rapid and revolutionary weapons development, had proven something of a farce.

The deal did not address the development and production of one of the First World War’s most effective weapons, the submarine. And, as time went by, all signatories failed to live up to the spirit, if not the letter, of the agreement.

The United States had worked around the terms and developed technology to boost their ships’ performance. The United Kingdom, representing the British Empire, including Canada, exploited a loophole. Italy misrepresented its vessels’ tonnage. Citing Britain’s faithless actions, France built bigger ships.

Finally, Japan called the whole exercise unfair and simply walked—make that sailed—away, ultimately launching an attack on the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor that resonates in the American consciousness to this day.

None of the signatories faced significant repercussions for breaking the faith. By that infamous day in December 1941, two of them—Japan and Italy—were at war with the rest, a world war that, in the East and the West, hinged on naval power.

Ironically, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, a former embassy representative in Washington who went on to mastermind the Pearl Harbor attack, was among the strongest proponents of Japan staying in the Washington Naval Treaty.

“Anyone who has seen the auto factories in Detroit and the oil fields in Texas knows that Japan lacks the power for a naval race with America,” he said, inviting the wrath of Japanese nationalists.

Despite the treaty’s failings, much can be learned from the aims of the century-old agreement, said Michael Neiberg, chair of war studies at the United States Army War College in Pennsylvania.

The treaty was one of three negotiated by nine countries meeting in Washington that fall. The conference came on the heels of a monumental conflict and devastating pandemic that, together, claimed an estimated 70 million lives.

“What they tried to accomplish is at least worth considering today to deal with COVID-19,” Neiberg wrote last year as the new pandemic spread havoc in virtually every sector of society.

“Reducing uncertainty should be a primary aim for all of the major players on the world stage as they think through how to deal with the post-coronavirus environment,” he wrote in War Room, the college’s online journal.

He predicted the U.S. and its closest allies will face enormous recovery costs—in fact, they already are—while at least two of America’s rivals, Iran and China, also confront significant challenges due to a virus that has claimed approximately five million lives worldwide and ravaged global economies.

“All have been hit hard by the pandemic,” Neiberg said. “Now is not the time for nations to look for windows of opportunity to launch aggressive moves. Rather, now is the time for international collective efforts.”

For those of us raised with the prospect of nuclear annihilation hanging over our heads, conducting Cold War-era air raid drills in dank school basements, ‘arms control’ is often construed as ‘preservation of the human species.’

But arms control is typically about stability and mutual security. And many arms control agreements are also about something much more pedestrian: spending.

In 2020, the U.S. Department of Defense spent US$139 billion of its $690-billion annual budget on the procurement of weapons and systems. It spent another $100 billion on research and development of weapons and equipment.

Two Harvard economic professors, David M. Cutler and Lawrence H. Summers, estimate the coronavirus will cost the U.S. more than $16 trillion in lost output, relief and eradication. The International Monetary Fund warned that the pandemic’s final bill for 2020 would total $28 trillion in lost output worldwide.

“The treaties produced by the Washington Conference contributed to the relatively peaceful 1920s,” asserted Neiberg. “The world today is obviously not the same as that of a century ago. Still, in this era of uncertainty and increasing great power competition, it might be worth revisiting the basic ideas that informed the Washington Conference.”

The term ‘industrialized warfare’ forced its way into the lexicon.

Stopping, or at least limiting, investments in particularly disruptive technologies such as hypersonic weapons might be a place to start, said Neiberg. Caps on ground forces, naval tonnage, nuclear warheads and missiles might be another.

“The winners in such a deal would be the states that see recovery from coronavirus as more important than the great power competition issues they had prioritized just a few long weeks ago.”

Land mines and unexploded cluster bombs litter landscapes in war zones.

The First World War marked a turning point in the technologies of death and destruction. With the introduction of machine guns, chemical weapons, airplanes and tanks, and refinements that made them more effective, along with myriad other developments, the term ‘industrialized warfare’ forced its way into the lexicon.

Whatever myths of romance and glory that had endured in 19th-century warfare did not survive the Western Front. The horrors and mass killing through two world wars would inform what was to come in terms of arms control, but the power and influence of emerging weapons giants—including Lockheed Martin, Boeing, Northrop Grumman, Raytheon Technologies and General Dynamics—seemed disproportionate to the wants and concerns of the average, peace-loving global citizen.

Technologies have continued to outpace humankind’s ability to control them, save for nuclear arms and the harsh lessons of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Chemical and biological weapons have flourished despite repeated efforts to eradicate them. Land mines and unexploded cluster bombs litter landscapes in war zones such as Afghanistan, flying in the face of treaties negotiated in Ottawa and Oslo banning them.

Lethal arms are widely available and controlling them is no walk in the park. Americans can’t even control the proliferation of firearms within their own borders. The fact that no ill-intentioned group acquired nuclear weapons after the Soviet Union collapsed is no small miracle.

Today, rogue states like North Korea and Iran and terrorist organizations such as al-Qaida and the Islamic State operate outside the tenets of international convention, restricting the scope of any agreements and rendering efforts at control and verification difficult if not impossible.

While they represent the extremes confronting arms control advocates, the challenges are not limited to traditional bad actors. Indeed, in the 100 years since the Washington Naval Conference, the history and achievements of arms control agreements have been sketchy, save for a few significant successes.

Deals to curb arms development and stockpiling tend to have names so long they appear to leave virtually nothing to chance. The 1925 Protocol for the Prohibition of the Use in War of Asphyxiating, Poisonous or other Gases, and of Bacteriological Methods of Warfare is mercifully known simply as the Geneva Protocol.

Countries (namely Colombia) were still joining as recently as 2015. Thirty-eight states originally signed the deal following years of horrendous chemical weapons development that came to a head during the First World War, when chlorine, phosgene and mustard gas were used to devastating effect by all sides.

First used on a large scale by German troops at Ypres, Belgium, in April 1915 the attacks were in clear violation of the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907.

Japan, one of the original signatories of the protocol, used chemical weapons on Chinese soldiers and civilians during the Second Sino-Japanese War in the 1930s and into the Second World War, even leaving behind some chemical field munitions when it abandoned its occupation of the Aleutian Islands in 1943.

The Americans, British and Germans all maintained stockpiles of chemical weapons throughout the Second World War, but never used them in battle. The Nazis used a cyanide-based pesticide, Zyklon B and other gases to murder millions of Jews and others during the Holocaust.

In December 1943, an American ship loaded with 2,000 mustard gas bombs was sunk during a German air raid on the harbour at Bari, Italy, poisoning at least 628 military personnel and medical staff along with untold numbers of civilians. At least 83 hospital patients died from the gas, but the incident was covered up and the final tally has never been calculated.

Iraq joined the agreement in 1931, yet future President Saddam Hussein would use mustard gas and nerve agents liberally against Iranian troops throughout their eight-year war of the 1980s and on Kurdish minorities in 1988 and 1991.

Chemical weapons were so ubiquitous in Iraq that Hussein’s defence minister and intelligence chief, Ali Hassan Abd al-Majid al-Tikriti, was known around the world as “Chemical Ali.”

Their laboriously long titles notwithstanding, the devil lies in the details of treaties of any kind. Diplomatic language and negotiation are rife with nuance, and the delicate subject of arms control may be the epitome of the art.

Besides blatantly or surreptitiously violating their dictates, signatories to arms control agreements often negotiate vague language, exploit loopholes and otherwise find ways to undermine a deal’s intent or impact in efforts to enhance their own interests.

So, on the face of it, while a country might look good and cultivate stature as the signatory to an agreement, its endorsement may well be watered down or rendered meaningless by the small print.

Some signatories, for example, attach reservations to their endorsements that “exclude or…modify the legal effect of certain provisions of the treaty in their application to that State,” explains the office of the United Nations Treaty Collection.

“A reservation enables a state to accept a multilateral treaty as a whole by giving it the possibility not to apply certain provisions with which it does not want to comply,” it says. “Reservations can be made when the treaty is signed, ratified, accepted, approved or acceded to. Reservations must not be incompatible with the object and the purpose of the treaty. Furthermore, a treaty might prohibit reservations or only allow for certain reservations to be made.”

The Geneva Protocol is riddled with reservations, including by the United States, United Kingdom, Russia and China, all of whom declared the agreement’s non-use obligations contingent on compliance by other states.

Several Arab states asserted that their ratifications did not amount to recognition of, or diplomatic relations with, Israel or declared that the protocol’s provisions were not binding with respect to Israel. This is obviously “incompatible with the object and the purpose of the treaty.”

There are 145 parties to the Geneva Protocol…and there are 113 reservations.

The terms of the Washington Naval Treaty were modified by two subsequent London treaties. But by the mid-1930s, Japan and Italy had renounced the whole concept of limits on their navies’ development and growth.

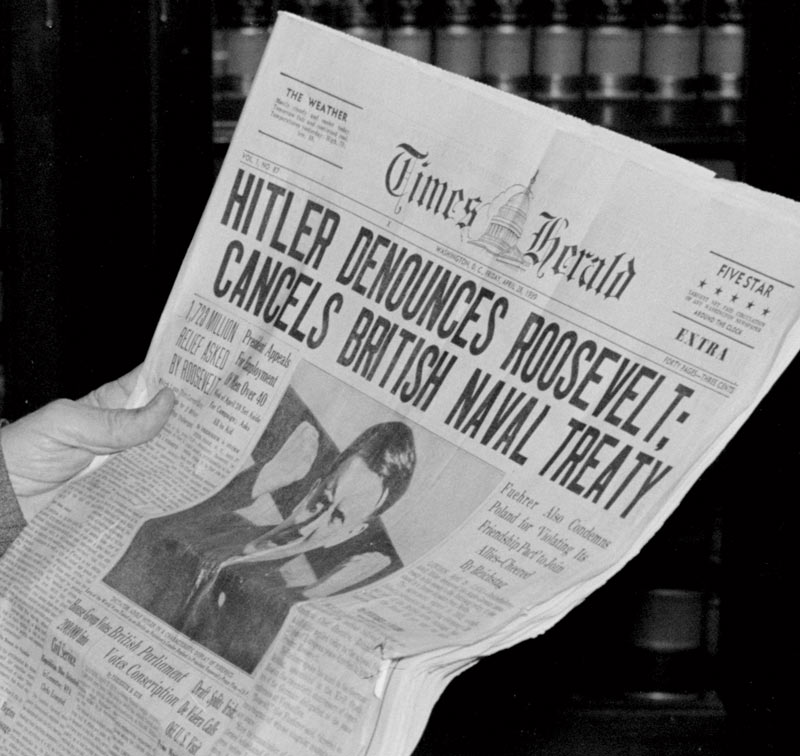

As Nazism took hold in Germany, Berlin renounced the punitive Treaty of Versailles, which had imposed harsh penalties for the country’s role in the First World War, placing strict limits on its military, including its navy.

In 1935, Britain and Germany came to terms under the Anglo-German Naval Agreement, which limited the tonnage of the Kriegsmarine to 35 per cent of the Royal Navy’s.

The agreement was doomed from the start. Its tenets broke the terms of the Versailles treaty, and Britain negotiated it without consulting key allies. Germany saw it as the birth of an Anglo-German alliance against France and the Soviet Union. Britain considered it the beginning of a series of arms control agreements designed to limit German expansionism.

On Sept. 30, 1938, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain trusted Hitler enough to sign a peace pact with him. “I have returned from Germany with peace for our time,” he declared on his return to London.

In April 1939, Hitler denounced the 1935 deal, four months before he invaded Poland, launching the Second World War.

Chamberlain resigned as France fell to German forces in May-June 1940. He was succeeded by Winston Churchill—a leader for his time.

Most arms control violators do their violating under wraps, knowing how difficult it is for monitors to prove their misdeeds.

The fundamental shortcoming of arms control is verification. Assessing a state’s compliance with the tenets of an agreement requires a difficult trade-off between transparency and security notes a 2020 study in the American Political Science Review.

Inspections are intrusive and potentially compromising to state security because they allow inspectors the opportunity to gather information—intelligence—that could be useful in a future conflict. Commitments, then, are hard to come by.

“Arms control is exceedingly rare historically, so that arming is ubiquitous and its costs to humanity are large,” wrote political scientists Andrew Coe and Jane Vaynman in their paper, Why Arms Control Is So Rare.

“To be viable, any deal must satisfy a transparency requirement and a security requirement. To ensure the compliance of the side that could arm, the probability that its cheating will be detected must be high enough: monitoring must render this side’s arming sufficiently transparent.

“However, the information revealed by monitoring also cannot give the monitoring side too large a military advantage: that is, the deal must be secure for the arming side. The problem is that transparency may reveal not only a state’s arming decision, but also other information relevant to the balance of power.”

NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg has said the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, which was signed in 2017 and took effect in January, is not viable because it’s not verifiable.

“The ban treaty has no mechanism to ensure the balanced reduction of weapons, no mechanism for verification,” he said. He advocated for continued efforts under the 1970 Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons to reduce and ultimately eradicate nukes.

That discouraging assessment comes in when hundreds of satellites and other methods of data collection allow unprecedented access to the happenings inside potential enemies’ borders.

But the consensus is—has to be—that, despite its flaws, arms control is worth the effort. Verification may be frustratingly ineffectual at times, but it has its benefits, beyond the success or failure of its core intent, said Dinshaw Mistry, a professor of international relations and Asian studies at the University of Cincinnati.

“Judging arms control as a process rather than an outcome provides the best understanding of the issue,” Mistry wrote in 2008. “Arms control serves to maintain an active diplomatic relationship between states during periods of tension and provides a forum for dialog on military issues.

“While arms control successes often follow a thaw in political relations between antagonistic states, these successes in turn foster better political relations between states, which allows for greater [confidence-building measures] that consolidate and institutionalize political cooperation.”

Trust and co-operation, of course, ebb and flow with leadership and the times in which they lead.

The Second World War and the Cold War that followed would produce new alliances, radical new technologies and a critical new age in which arms control agreements took on even greater import, demanding more trust and co-operation than many thought possible.

—

Major arms control agreements between the wars

Washington Naval Treaty

It was the central achievement of the Washington Naval Conference, which began in November 1922 with nine countries: the United States, Japan, China, France, Britain, Italy, Belgium, Netherlands and Portugal. Three major treaties and several smaller agreements were signed at the conference.

The pacts strictly limited size and production of capital ships and aircraft carriers proportionately among the signatories. Japan renounced the five-party agreement in 1934 and it was abandoned altogether two years later.

Protocol for the Prohibition of the Use in War of Asphyxiating, Poisonous or other Gases, and of Bacteriological Methods of Warfare (Geneva Protocol)

Coming in 1925, two decades after the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907, the Geneva Protocol prohibited the use of chemical and bacteriological warfare. But confoundingly, it did not address the production, storage or transfer of chemical and bacteriological weapons. (The 1972 Biological Weapons Convention and the 1993 Chemical Weapons Convention did.) Despite its shortcomings, the protocol has been ratified by 145 countries and remains the standard for chemical and biological weapons control.

Advertisement