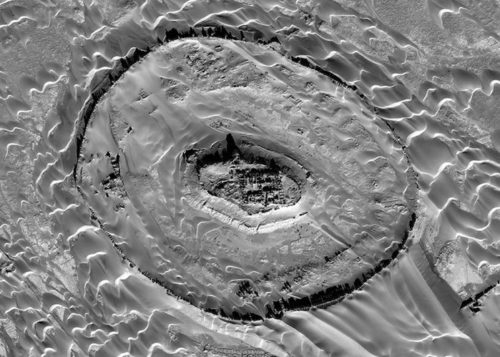

Aerial imagery of Tar-o-Sarb shows the remains of an ancient Parthian civilization.

[Digitalglobe Inc.]

Archeologists were summoned and a drone dispatched, revealing a dual track arcing from one side of the pasture to the other. One might have concluded it was a very large tractor trail in these pastoral parts near the River Lahn. But it wasn’t.

It turned out to be the remnants of a defensive double ditch on the perimeter of a 2,000-year-old Roman army encampment.

Further investigation would reveal about 40 wooden towers around the eight-hectare site, along with evidence of silver mining. The find also yielded a Roman-era first—well-preserved wooden stakes, sharpened to deter enemy attacks.

Julius Caesar had referenced such defences, comparable to present-day barbed wire and razor wire, in his writings. But none had ever been found.

If not for the perceptive and conscientious hunter in his high perch, and the archeologists’ drone with its overhead perspective, the ancient encampment might never have been discovered.

Indeed, overhead views provided by satellites and drones, sometimes equipped with ground-sensing technology, have opened new doors to archeological research in recent decades, revealing subtle variations in the colour and makeup of terrain in fields and meadows, jungles and forests, shallow waters and deserts, betraying secrets right under our noses and in some of the world’s most remote places.

In Afghanistan, spy satellites have uncovered lost Silk Road outposts and traces of vanished empires in the forbidding desert regions of a warring land. Among the finds: huge 17th century caravanserai—waypoints used by Silk Road travellers for millennia—and subterranean canals long-buried by desert sands.

The mudbrick waystations could accommodate hundreds of people and their livestock. Like modern-day motels, campgrounds or highway rest stops, they were distributed every 20 kilometres, the distance caravans averaged in a day.

The sites were too dangerous to explore in person, so a remote mapping project funded by a multimillion-dollar grant from the U.S. State Department enabled researchers to study Afghanistan’s archeological heritage from afar.

The lost caravanserais of the Silk Road in Afghanistan were uncovered using satellite imagery. Here, a satellite image of a 17th century carvanserai, or waystation. [Digitalglobe Inc.]

They are believed to have begun to disappear after sea routes opened between India and China in the 15th and 16th centuries.

The journal Science reported in 2017 that, inspired by the discoveries, researchers re-examined images collected in the 1970s. They revealed hidden canals threading through Afghanistan’s Helmand and Sistan provinces, likely built during the Parthian Empire between 247 BC and AD 224.

The imagery has also exposed the melting pot of religions that once thrived in the landlocked country, including Zoroastrian fire temples and Buddhist stupas—the very cultures the Taliban were seeking to erase when they destroyed the giant Buddhas of Bamiyan in March 2001, causing a wave of pre-9/11 outrage.

Deserts have proven fertile ground for archeologists seeking to discover lost worlds via overhead imagery.

Back in 2011, satellite photographs uncovered more than a hundred fortress settlements from a lost civilization in the Sahara Desert of southwestern Libya.

Calling them “real-life castles in the sand,” National Geographic reported that the communities dated to between AD 1 and 500. They were determined to have belonged to an advanced but mysterious people called the Garamantes, who ruled from roughly the second century BC to the seventh century AD.

Researchers uncovered walled Garamante towns, villages and farms after poring over satellite images, including high-resolution photographs commissioned by the oil-and-gas industry, along with aerial photos taken during the 1950s and 1960s.

Located about 1,000 kilometres south of Tripoli, the origins of the fortresses—some walls still stood three- to four-metres high—were confirmed by pottery samples collected during an early-2011 expedition. The effort was cut short by the civil war that ended the 42-year regime of Libyan leader Moammar Gadhafi.

“It is like someone coming to England and suddenly discovering all the medieval castles,” David Mattingly, a professor of Roman archeology at Leicester University, told The Register at the time. “These settlements had been unremarked and unrecorded under the Gadhafi regime.”

Mattingly said the findings suggested an advanced civilization, not the uncouth barbarian nomads the Romans described.

“In fact, they were highly civilized, living in large-scale fortified settlements,” he said. “It was an organized state with towns and villages, a written language and state-of-the-art technologies. The Garamantes were pioneers in establishing oases and opening up Trans-Saharan trade.”

The remote sites apparently escaped the wrath of the Islamic State group, or ISIS, which looted and destroyed other ancient locations in Libya and Syria in the last decade.

Ancient Romans topped a fence with sharpened wooden stakes to deter enemies.

[Frederic Auth/Goethe University]

Mattingly said the findings suggested an advanced civilization, not the uncouth barbarian nomads the Romans described.

Satellite imagery from the Corona project, a Cold War spy program that collected military intelligence about the Soviet Union and its allies, has spawned a latter-day archeological boon.

A trove of some 850,000 images that were taken by Corona satellites between 1960 and 1972 are currently providing leads to potential ancient sites hidden from even the probing eyes of satellites by urban sprawl and other development.

Reviewing images declassified in the mid-1990s, Harvard University archeologist Jason Ur has discovered communication networks of the early Bronze Age, state-sponsored irrigation under the Assyrian and Sasanian empires, and pastoral nomadic landscapes in northwestern Iran and southeastern Turkey.

By 2021, the University of Arkansas’ Center for Advanced Spatial Technologies had compiled a publicly available database of more than 2,200 Corona photographs identifying 803 archeological sites.

Centre researchers developed Sunspot, a free open-access system for mapping Corona imagery to terrain captured by Google Earth.

“Corona’s 20th-century images are a valuable supplement to today’s satellite shots, drone photography, and imaging technology, such as LiDAR [light detection and ranging], a once prohibitively expensive means of gathering topographic data which is being increasingly funded by government agencies, yielding an unimaginable wealth of archaeological discoveries,” Sarah Cascone wrote for Artnet.

Likewise, drones have opened new opportunities for archeological exploration, putting an invaluable tool in the hands of researchers and the general public alike.

“The influence of drones on archaeological discoveries and excavations has been nothing short of revolutionary,” Marcin Frąckiewicz wrote for TS2, a Warsaw-based satellite services provider.

“These small, unmanned aerial vehicles have been instrumental in unearthing ancient secrets and shedding light on the mysteries of the past. With their ability to capture high-resolution images and cover vast areas in a short amount of time, drones have significantly impacted the field of archaeology, changing the way researchers approach their work and uncover hidden treasures.”

Once dependent on expensive, time-consuming and even dangerous methods such as ground surveys, aerial photography and satellite imagery, archeologists can now easily navigate and photograph once-forbidding terrain, and do so non-invasively.

Hunter Jürgen Eigenbrod first spotted these markings in a German field. They turned out to be traces of changes in vegetation from ancient Roman ditches.

[Hans-Joachim du Roi]

“The influence of drones on archaeological discoveries and excavations has been nothing short of revolutionary.”

Drones equipped with advanced imaging technology such as LiDAR can create detailed 3D maps of sites while at the same time preserving them and allowing researchers to analyze data and prioritize areas of interest.

“Drones have also played a crucial role in capturing the public’s imagination and fostering a greater appreciation for archaeology,” wrote Frąckiewicz. “Stunning aerial images and videos of archaeological sites captured by drones have been widely shared on social media, sparking interest and curiosity among people of all ages. This increased awareness and fascination with the past have, in turn, led to more support for archaeological research and preservation efforts.”

LiDAR works by shooting lasers at the ground and measuring how much light is reflected. Researchers can then determine the distance from the drone to solid objects between the vegetation, creating a rough 3D model of the terrain.

In 2021, a Spanish archeological team used LiDAR-equipped drones to chart ancient battlefields on the Iberian peninsula.

“The exploration and recording of buried archaeological features using technologies that leave the structures untouched in the ground represents the cutting-edge frontier of field archaeology,” Paula Uribe et al wrote in the March/April 2021 edition of the Journal of Cultural Heritage.

“This form of exploration is even more useful in the archaeological investigation of battlefields, a particular kind of territorial archaeology where sites may go unnoticed in a traditional archaeological survey.”

Also in 2021, LiDAR-equipped archeologists found evidence of 478 Mesoamerican sites built by the Maya and the Olmec in Mexico between about 1400 BC and AD 1000.

And in 2016, a LiDAR-equipped drone revealed the ancient Cambodian city of Mahendraparvata.

Hidden deep in the jungle under a cloak of thick vegetation on the mountain of Phnom Kulen, the once-mighty metropolis was an early capital of the Khmer empire, which ruled in Southeast Asia between the 9th and 15th centuries.

Satellite and drone images led archeologists to the 2016 discovery of a massive ceremonial platform beneath the sands at Petra, the 2,200-year-old Jordanian trading centre that provided the backdrop for the climactic scenes in the movie Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade.

Christopher A. Tuttle of the Council of American Overseas Research Centers said the platform was not clearly visible from the ground, and that only images taken from above revealed the shape. No digs were planned at the time.

Archeologists are even counting on satellites to help them find some of the three million shipwrecks that are scattered across the world’s oceans.

In 2018, British and Brazilian archeologists found traces of 81 pre-colonial settlements in Brazil’s upper Tapajós basin. The aerial surveys revealed the remains of dozens of geoglyphs—mysterious, geometric earthworks that may have been used during ritual ceremonies.

“Villages have often been found near, or even inside geoglyphs, and when archaeologists explored 24 of the sites uncovered by the satellite images, they unearthed stone tools, ceramic fragments, garbage piles, and terra preta, an enriched soil that has been found in other parts of the Amazon,” said Smithsonian Magazine.

The Guardian reported the team also discovered evidence of fortifications, sunken roads and platforms where houses once stood. The sites were dated to between AD 1410 and 1460.

Archeologists are even counting on satellites to help them find some of the three million shipwrecks that are scattered across the world’s oceans; a quarter are believed to be resting on the bottom of the North Atlantic.

In a 2016 study published in the Journal of Archaeological Science, marine geologist Matthias Baeye at the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences et al explained that wrecks produce suspended particulate matter (SPM) that can be detected by high-resolution ocean colour satellite data such as that of NASA’s Landsat-8.

Distinctive linear plumes of these particles extend more than four kilometres downstream from shallow shipwreck sites and are easily detectable from space.

“Landsat-8 data is free and therefore the method presented in the study is an inexpensive alternative to acoustic and laser survey techniques,” the team wrote.

The researchers analyzed four known wreck sites near the Port of Zeebrugge on the Belgian coast, all located within five kilometres of each other on a sandy sea floor in less than 16 metres of water.

Two ships, Sansip and Samvurn, sank after hitting mines during the Second World War. The Swedish steamship Nippon collided with another vessel in 1938, while Neutron, a Dutch steel cargo transport, went down in 1965 after hitting what is believed to have been the Sansip wreck.

Using tidal models and a set of 21 cloud-free Landsat-8 images, the researchers mapped sediment plumes extending from the wreck locations of Sansip and Samvurn, but got no results from Neutron and Nippon, which are buried deeper in the seabed.

“SPM plumes are indicators that a shipwreck is exposed at the seabed and certainly not buried,” the researchers wrote.

It was not certain at the time whether depth limits the new wreck-detecting methodology since the four wrecks in the study are in relatively shallow waters.

Nevertheless, the researchers maintained “the ability to detect the presence of submerged shipwrecks from space is of benefit to archaeological scientists and resource managers interested in locating wrecks.”

Advertisement