Seventy-five years ago, the lights of Christmas 1946 twinkled and danced across Canada and throughout the Western world as they had for no other Yuletide celebration in what must have seemed, to many, an eternity.

Loved ones, families and friends had a lot to celebrate. The war was over, with any luck the boys were home, and 8.2 million babies had already started arriving in what would become known as the postwar baby boom. It lasted two decades.

Some servicemen were meeting their children for the first time after long years overseas. It could be an awkward process, getting to know the dad whose life was so altered by such extraordinary circumstances. They didn’t tend to talk about it much and the getting-to-know-you part would be, for some, a lifelong pursuit.

The consequences of six years of war would reverberate for generations, perpetuated, in large part, by the fact that many of the ties servicemen had forged—on stormy mid-Atlantic seas, in foxholes and ruins, in Quonset huts and khaki tents—had been severed, replaced by a love and tenderness many a young fighting man had never known.

Some beaus had left as boys and returned entirely different men.

There were newlyweds and war brides, sweethearts and romances born of long, dogeared letters, folded and unfolded and folded again, read and re-read in solitary moments overseas and on the homefront, eventually to be stuffed in shoeboxes and stashed away in attics and basements.

There were couples, too, who were finding out that, in spite of their soaring wartime romances, even weddings, they barely knew each other. Some beaus had left as boys and returned entirely different men. Some returned to learn the love they had counted on had ended. Some didn’t return at all.

Of the 1.16 million Canadians who served in the Second World War, more than 42,000 had been killed. Some 54,000 were wounded, many saddled with life-changing injuries, physical and psychological.

In the years before operational stress injury and post-traumatic stress were identified and more effective treatments developed, many a war veteran—and their families—suffered the consequences.

Legion halls became their confessionals, places where they could gather over beers with like-minded veterans who shared similar wartime experiences. The booze helped lower the defences; the talk soothed troubled souls. Sometimes, there was more booze than talk.

But all that would come later. For now, at least, the returnees were typically grateful they had survived and joyous in their victory, in their homecoming and in the prospects for some measures of happiness and prosperity, tempered by the knowledge that friends and comrades lay buried in foreign soil or deep beneath the waves of vast oceans far away..

As the realization set in that they were free of the lingering possibility their lives could end at any moment with the strike of a torpedo, a random piece of flying shrapnel, a simple misstep on a mined pathway or the impact of a sniper’s bullet, long-term hopes and dreams—possibilities—stirred back to life.

There would be disappointments and heartbreak enough down the road. But this Christmas, the first Christmas the bulk of Canadian servicemen were back from postwar occupation duty, there was much to celebrate.

It’s a Wonderful Life film poster. [Wikipedia]

Christmases of the recent past had been understated affairs marked by absence, anxiety and deprivation brought on by wartime shortages and rationing that even affected toys, which had been made of wood, not metal.

Excessive consumption of resources—electricity, furnace oil, gasoline—had been discouraged, if not banned outright.

By 1946, supply was ramping up again, so much so that the National Outfit Manufacturer’s Association Electric Corporation came out with “bubble lights,” which had been invented but not marketed in the 1930s. NOMA’s sealed glass tubes containing coloured bubbling liquid were a hit.

NOMA bubble lights.

Christmas parades, suspended during the fighting overseas, were making a comeback.

“The Junior Chamber of Commerce’s annual Christmas parade, a wartime casualty, will be revived this year and will be the largest, best Christmas parade the city has ever had,” parade chairman J.B. Willett was quoted as saying in the Nov. 28, 1946, edition of The Fredericton Gleaner.

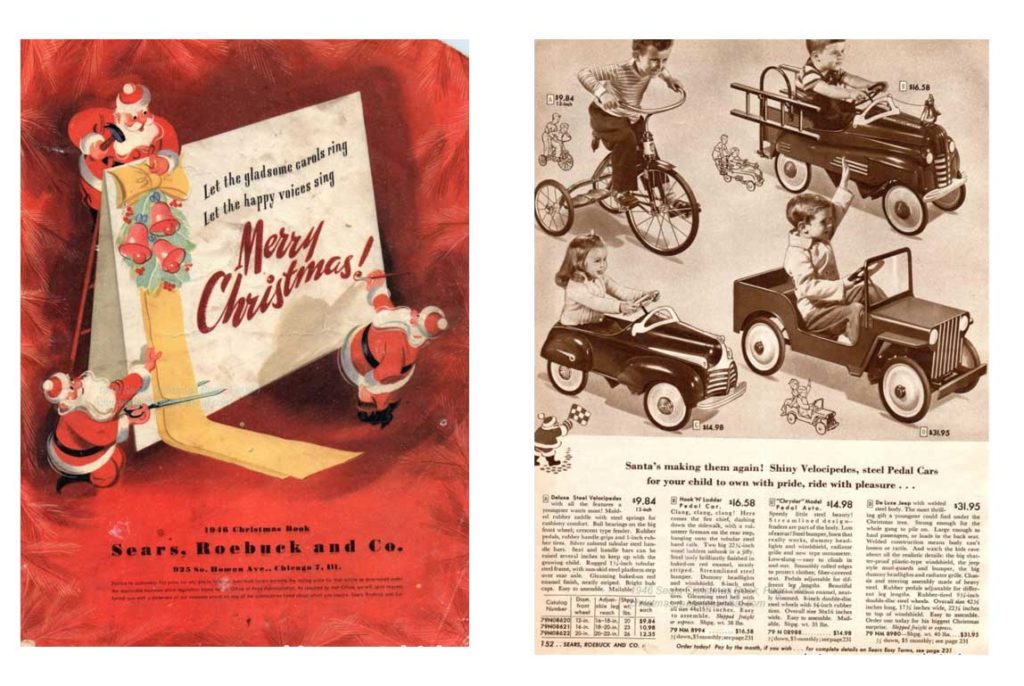

Christmas tree sales were up. The cover of the 244-page Sears, Roebuck and Co. Christmas catalogue declared “Let the gladsome carols ring/Let the happy voices sing.”

The book had many items tailored for new families—tools, bedding, bassinettes and all manner of toys, the bulk of them, it seems, for toddlers and young children. There was even a Willy’s-style “De Luxe” peddle Jeep with a welded steel body for $31.95. That converts to a whopping $452.57 in 2021 value.

The domestic situation wasn’t all roses in the war’s immediate aftermath.

And a wheelchair at $107, “a Gift to bring new freedom and comfort to the invalid.”

“Watch the look of pleasure when the invalid in your family sees this streamlined wheel chair,” it said. “It means liberation from the narrow range of the sickroom.”

Indeed, the domestic situation wasn’t all roses in the war’s immediate aftermath in Canada. In a population of just 12.3 million, military discharges and war industry layoffs had boosted the unemployed to a quarter-million in 1946, or about 3.4 per cent of the workforce. That compares to a wartime low of 1.4 per cent unemployment in 1944.

Labour unrest on both sides of the border was taking a toll on the automotive industry. General Motors had been shut down by strikes in its U.S. plants; Ford was recovering from a strike in Windsor, Ont., and Chrysler was behind in production.

But the slump didn’t last. In 1947, unemployment fell to 2.2 per cent. New housing and infrastructure were in rising demand. The country was growing rapidly and the prosperity of the 1950s lay just ahead. So, too, did war on the Korean Peninsula, an arms race and a four-decade-long Cold War.

The 1946 Sears, Roebuck and Co. Christmas catalogue included a peddle Jeep for $31.95. [https://christmas.musetechnical.com]

But that Christmas—Christmas 1946—would be marked by a common theme among Canadians and their wartime allies: hope.

Advertisement