An unidentified soldier wearing a Union Army uniform and holding a musket stands in front of an American flag in the early 1860s. [Library of Congress/LC-DIG-ppmsca-31117]

It can be extraordinary who and what you will find when digging into family history. In an article for Legion Magazine last year, CBC journalist Murray Brewster wrote about the Battle of Ridgeway and the eyewitness account of his great-great-grandfather, a doctor and United States Civil War veteran, who in June 1866 tended wounded and dying Canadian soldiers and Fenian raiders (May/June 2018). His research opened the door to an even more intriguing story about his ancestor’s war service, the thousands of Canadians who served on both sides of that cruel and bloody conflict, and how the divided loyalties among our southern neighbours spilled across the border.

The Confederate soldiers on the riverbank opened up with a violent stream of fire that poured through the gun ports of the Union gunboat USS Signal. It was later described as “a perfect storm of mini-balls.” Surprisingly, no one was killed.

As each whistling fusillade evaporated, wounded sailors picked themselves up off the deck of the converted wooden paddlewheeler, which had been wrapped in tin and armed with four 24-pound howitzers. They resumed their stations and continued sniping in return. It was, however, a losing battle.

“By now the gunboat men had expended some 330 shells, but were no safer,” wrote author Myron J. Smith Jr. in his book, Tinclads of the Civil War.

USS Galena, a Union Navy wooden-hulled ironclad steamer, was a typical Civil War-era battleship. [James F. Gibson/Library of Congress/LC-B811-488]

Signal had been doing convoy duty on the Red River in Louisiana, escorting Union troop steamers up and down the waterway during the ill-fated 1864 Red River Campaign. Confederate cavalry and artillerymen, more familiar with each bend and curve, would lay particularly ferocious and effective ambushes.

On the morning of May 5, 1864, Signal, a sister ship, USS Covington, and a transport, John Warner, were caught in one of those assaults, 40 kilometres southeast of Alexandria, Louisiana. They had been trying to make their way downriver toward New Orleans when the trap was sprung.

After a furious exchange of fire, John Warner was captured, with many dead and wounded. Covington was set on fire and scuttled by its crew, which slipped ashore and scurried back to Alexandria along the riverbank.

Signal’s crew fought on as every Confederate gun and rifle was trained on the paddlewheeler. It was soon disabled and drifted into a bank. The abandon ship call was made along with preparations to burn the gunboat, according to Tinclads of the Civil War.

“In addition to the damage to the power plant and the steering gear during the six-hour engagement, the gun deck casements were penetrated 11 or 12 times by shot and shell, several of which exploded on the gun deck,” Smith wrote. “One cut the steam pipe, another the steam drum, and one hit the port boiler. Many of the guns were out of action and the decks were covered in wreckage.”

Before it could be scuttled and the crew could escape, the gunboat was surrounded by Confederate soldiers. The captain chose to surrender and “a total of six officers and 48 crew members” were marched into captivity as prisoners of war.

Battle of Mobile Bay,” a lithograph by Louis Prang, depicts a battle in 1864 that was part of the Union Navy blockade of the Atlantic and Gulf coastline. During the blockade, Nathaniel Brewster served on USS Milwaukee, which struck a mine and sank east of Mobile, Alabama, in 1865. [Louis Prang/Library of Congress/LC-DIG-pga-04035]

Among them was my great-great-grandfather, Nathaniel Brewster, a surgeon’s assistant who had joined the Union Navy in March 1863. He was, at the time of his capture, a recently married man with an 18-month-old baby.

Brewster was born in 1837 in Ellisburg, N.Y., a sleepy community along the eastern shore of Lake Ontario, but he was, for all intents and purposes, a Canadian. His wife, Sarah, was Canadian and the young couple had made a conscious decision to settle in Ridgeway, Ont., following his medical training in Toronto and Victoria.

Given the political and social climate of the time, it was an unusual, perhaps even bold, decision on the part of the young physician. Canada was still a British colony and the deeper the U.S. Civil War became, the more Americans looked on their northern neighbours with suspicion and outright hostility. Britain and many parts of Canada were seen as waxing between sympathy and undisguised support for the Confederacy that was tearing the Union asunder.

Whether the Confederates who captured him were aware of his Canadian credentials is unclear, but after a few months at Camp Ford near Tyler, Texas, the largest Confederate-run prisoner-of-war camp west of the Mississippi, Brewster was set free. During the summer of 1864, the camp was bursting with Northern captives.

“The 4,725 inmates were overcrowded and critically short of food, shelter and clothing,” according to a synopsis by the Texas Historical Society. “Their plight was desperate for several months, until major exchanges of prisoners in July and October 1864 alleviated somewhat the shocking conditions that had prevailed.”

Among those exchanged were 39 Signal crew members, including Brewster, who returned home to his wife and daughter in Ridgeway, a pastoral village on the north shore of Lake Erie, a stone’s throw from the U.S. border. He returned to duty months later, leaving behind a wife pregnant with their second child, a daughter who would be born just weeks after he had escaped death a second time.

Officers on the deck of USS Monitor (bottom left), the first ironclad warship commissioned by the Union Navy. [James F. Gibson/Library of Congress/LC-B815-487]

This time his ship was USS Milwaukee, a 1,300-tonne river monitor that was part of the blockade force off Mobile, Alabama. The port had been closed in the summer of 1864, but the city remained firmly in Confederate hands and rebels had stitched the shallow waters, including the nearby Blakely River, with mines.

It was the twilight of the Civil War in March 1865 when the Union army commander in the western Mississippi, the stern, taciturn Major-General Edward Canby, decided to move on Mobile.

His troops would attack from the east, rather than the west where the city was defended by a series of fortified ports. The key was Spanish Fort on the east bank of the Blakely River.

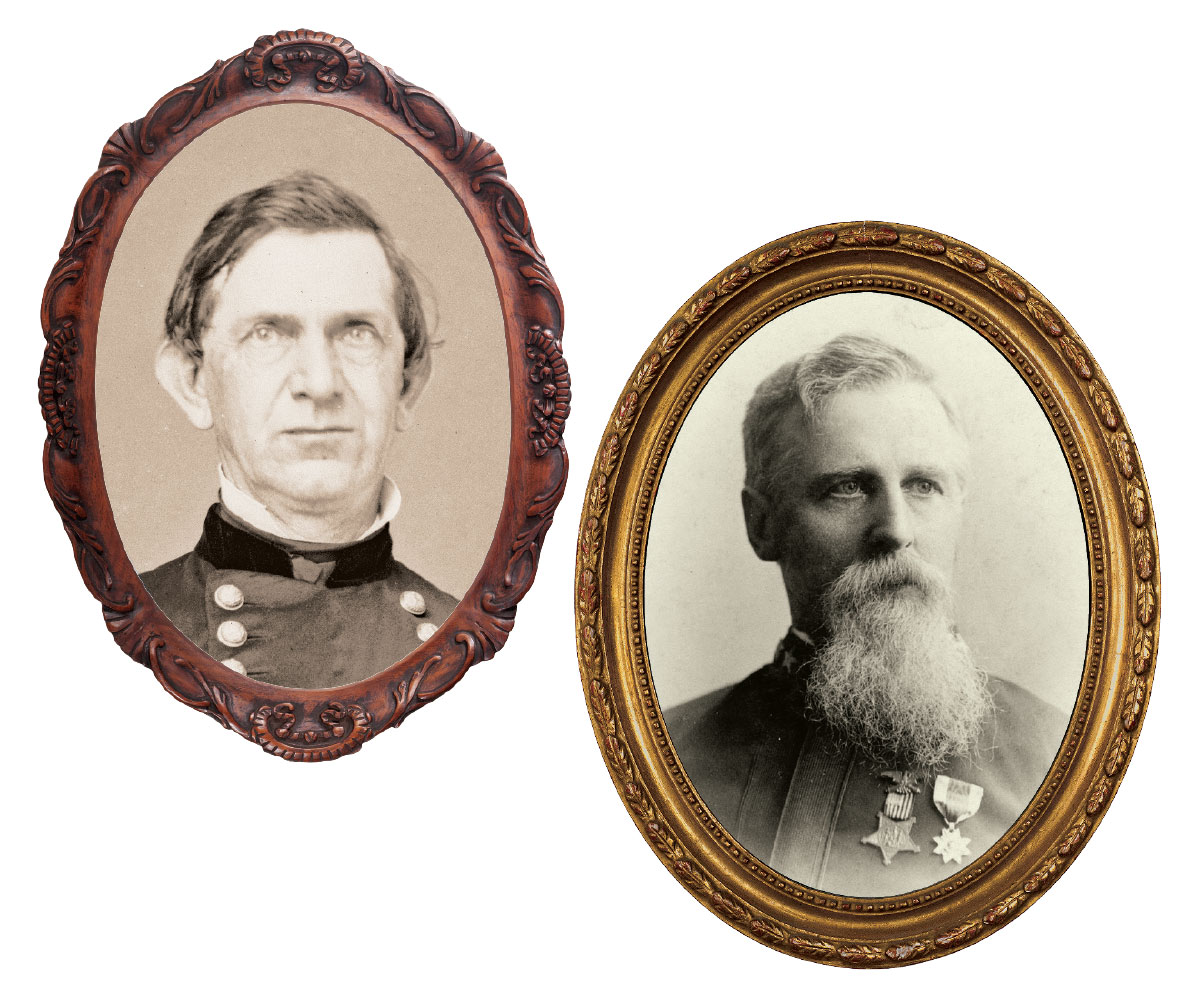

Major-General Edward Canby (left) ordered the attack on Mobile. Lieutenant-Commander James Henry Gillis (right) was Brewster’s commander aboard USS Milwaukee. [Library of Congress/LC-B813-6575; Bonnie Gillis Waters/Princeton University]

Milwaukee and five other Union ships were sent upriver on March 27, 1865, to cut communications between the fort and Mobile. The skipper was the tough as nails Lieutenant-Commander James Henry Gillis, who gave chase when he spotted a Confederate troop transport the next day. The prey swiftly retreated and outran both Milwaukee and her sister ship USS Winnebago.

As they gave up the chase and turned downriver, Milwaukee struck a mine in a patch of the river that had reportedly been swept. The blast tore a gaping hole in the port bow. The warship began to settle at a slow, steady rate. Gillis gave the abandon ship order—the second time in less than a year my great-great-grandfather would have heard that cry.

There was enough time to evacuate all 120 men and officers without loss of life. Most were taken aboard another sister ship, USS Kickapoo.

The good fortune helped Gillis’ reputation. When he retired as a rear admiral some years later, he was known as a sailor with “a charmed life” because he’d never lost anyone under his command.

But the loss of his ship seemed to enrage Gillis, who swam ashore and volunteered to command a naval shore battery. He fought tenaciously and history credits him with assisting in the capture of Spanish Fort. Later promoted for his actions, Gillis received a special commendation from Gideon Welles, President Abraham Lincoln’s secretary of the navy. Less than three weeks later, the war ended with the Confederate surrender at Appomattox Court House in Virginia.

Surgeons of the IX Corps’ 3rd Division pose in front of a hospital tent in Petersburg, Virginia, in 1864. Brewster joined the Union Navy as a surgeon’s assistant in 1863. [Library of Congress/LC-B817-7042]

It is a shame my great-great-grandfather never left a written account of his Civil War experience. Perhaps, he was eager to forget.

What little I was able to learn was pieced together through U.S. archives and a book on my family’s genealogy published in 1908, which places him among my notable ancestors. In later years, he spoke with pride about his time in uniform and was persuaded to write an eyewitness account of the Fenian raid on Niagara, which took place a little more than year after the end of the Civil War.

That account, written in 1911 on the 45th anniversary of the ill-fated Irish incursion, was seasoned with the kind of weighty comprehension that only an experienced veteran can provide. He understood the capriciousness of violence, recognized and appreciated bravery when he saw it, and reserved a healthy outrage for incompetence that wasted lives.

His story piqued the curiosity of author John Boyko, who has written extensively about Canadians who served in the seminal American war. The fact that Brewster, a married man in Upper Canada, volunteered in 1863, at the midway point in the conflict when the horrors had been scorched into the public consciousness, spoke volumes about his character.

“Most of the ones I found who joined were single,” said Boyko, author of Blood and Daring: How Canada Fought the American Civil War. “The other thing that is interesting is that he would join the navy, of all things. Why the navy, as opposed to the army? That’s interesting.”

More than 40,000 Canadians fought on both sides of the war, although the vast majority were with Union forces. More than 7,000 Canadians died in the four years of unrelenting bloodshed, and 29 were awarded the Medal of Honor, the highest military decoration in the U.S. Those who chose the navy came mainly from the East Coast, at a time when trade links with New England were stronger than the ties with Central Canada.

“Most of the Canadians who joined [the U.S. Navy] were from New Brunswick or Nova Scotia, which you can understand,” said Boyko. “They’re fishermen, people of the sea.”

The fact that someone from a largely landlocked region chose the navy was curious. It may have been the lesser of two evils, a compromise perhaps to his wife and young family who understood his desire to serve, the call of his heritage, but had no desire to see him condemn himself to certain fate.

“By 1863, there had been so many horrific battles,” said Boyko. “People knew that if you were going to go into the army, it was not a good time. Going into the army, you were as likely, or more likely, to die from disease as much as gunshot or artillery.”

The political and social context of the time also made his decision to serve an extraordinary one. It is largely forgotten today how openly pro-Confederate Canada’s fledgling media, political and business classes were throughout the Civil War, said Boyko.

Although he was recognized as an American, my great-great-grandfather’s decision to settle in Canada might have been looked on with suspicion. What most Americans didn’t realize was that support for the secessionists had nothing do with slavery, which had been abolished in the British Empire by an act of Parliament in 1833.

It had more to do with clear-eyed political self-interest.

At the outset, before the Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln said he was fighting to preserve the Union, a federal system that had grown increasingly hostile to British North America.

The American political class of the day believed in Manifest Destiny, a phrase coined in 1845, which held that the U.S. was destined—by God—to expand its dominion and spread democracy and capitalism across the entire continent. Think of it as the original America First. One of the more vocal supporters of Manifest Destiny was William Seward, Lincoln’s secretary of state, who had mused openly about annexing Canada.

Misgivings were heightened early in the war when the U.S. detained a British mail packet with two Confederate officials aboard. London threatened to declare war if the men were not released. Lincoln relented, but grudgingly.

President Abraham Lincoln (third from left), accompanied by cabinet secretaries and other officials, prepares to sign the Emancipation Proclamation, which freed slaves in the 10 states rebelling against the Union. [Wikimedia]

On Dec. 4, 1861, Lincoln met with Alexander Galt, the finance minister of the Province of Canada, at the White House and went out of his way to reassure him that the colony had nothing to fear from Washington.

“For himself and his Cabinet, he had never heard from one of his ministers a hostile expression toward us, and he pledged himself as a man of honour, that neither he nor his Cabinet entertained the slightest aggressive designs upon Canada, nor had any desire to disturb the rights of Great Britain on this continent,” Galt wrote in his official report.

But Galt was left unconvinced and wary, a mindset that was only reinforced by continued public musings of takeover by Lincoln’s cabinet and a growing hostility toward Canada in Northern U.S. newspapers.

“The temper of the public mind toward England is certainly of doubtful character, and the idea is universal that Canada is most desirable for the North, while its unprepared state would make it an easy prize,” Galt wrote. “The vast military preparations of the North must either be met by corresponding organization in the British provinces, or conflict, if it come, can have but one result.”

The Province of Canada was officially neutral as a British colony, but many Canadian newspapers openly supported the Confederacy, something that only deepened American anger and resentment in Union states. “We backed the wrong horse,” said Boyko.

There were many political reasons at the time “that kind of made sense,” but many of those justifications are made to look naïve, even foolish, in the long view of history.

“If the Confederacy had won, the United States would have split up, and it would not have split into two. It would have shattered and turned into a Europe, with the Copperheads taking a section out West,” said Boyko, referring to the anti-war faction of the U.S. Democratic Party, which demanded immediate peace and resisted draft laws. “It would have shattered into a bunch of small European countries and that would have been great for Canada and great for Britain. So, of course, we wanted the Confederacy to win from that point of view.”

The rhetoric of the time was overheated, but confined to what Boyko describes as “the chattering classes” and the political establishment. The beliefs and actions of “regular folks” in the 1860s were likely not much different than people today.

“Just because these things are being talked about in newspapers and in the halls of Parliament, it doesn’t translate into who you choose to fall in love with or where you make your life,” said Boyko.

The notion that the people, including my great-great-grandfather, were on a different page than the leadership and the opinion-makers of the day is further reinforced by the sheer numbers. Against that political and social backdrop, my great-great-grandfather and tens of thousands of other Canadians chose to fight. Whether it was a moral decision, a vote against slavery, a desire for adventure or a sense of duty, which was likely the case for Brewster, Canadians overwhelmingly flocked to join the ranks of the Union army, not the Confederacy.

Only 10 per cent of the Canadians who volunteered fought for the South. Part of the reason, said Boyko, lay in the fact that most of them were already living there.

As an interesting aside, he said, Canada and Britain never paid a political price for their Confederate leanings and that may be because tragedy intervened just days after the end of the war with the assassination of Lincoln.

“Lincoln said we were going to pay a price,” said Boyko, referencing the meetings between the president and Galt. What form the retribution might have taken is not clear. If Lincoln had lived, reconstruction of the South, which became a “horror show” in the president’s absence, would likely have had a completely different outcome. America, as a nation, also would not have turned inward the way it did following the assassination.

“That’s the great irony,” said Boyko. “It’s a tragedy that Lincoln was assassinated, but if he would not have been assassinated, I think we would have paid a price.”

Officers and crew aboard USS Hunchback in Virginia’s James River, circa 1864-65. [Naval History and Heritage Command/NH-59430]

Over the past few years, Americans have been pulling down Confederate war statues, many of them erected decades after the conflict. It is a long-overdue display of reconciliation with African-Americans, who more than 150 years later remain, in many ways, disenfranchised.

The Southern Poverty Law Center in Montgomery, Alabama, tracks the removal of monuments. It estimates that at least 110 publicly supported statues and tributes, such as plaques and street names, have been removed. It is a drop in the bucket compared with the roughly 1,700 that still remain.

Mitch Landrieu, the mayor of New Orleans who led the charge to topple the monuments in his city, described the Confederacy as being on the “wrong side of humanity” and that the statues and memorials represent a false, romanticized view of history.

“These statues are not just stone and metal,” Landrieu said in 2017. “They are not just innocent remembrances of a benign history. These monuments purposefully celebrate a fictionalized, sanitized Confederacy, ignoring the death, ignoring the enslavement and the terror it actually stood for.”

There are some in the U.S. who argue that the monuments honour the soldiers who fought for the South and reject the notion those men were not necessarily going to war to preserve the institution of slavery. It is a claim often made by defenders of the so-called Lost Cause narrative of the Civil War, a revisionist historical view that wipes clean the injustice and attempts to comb out the tangled inhumanity.

What motivated men to fight on either side of that brutal war is not, in my estimation, as tidy and easily explained as 21st-century sensibilities demand.

That was the point a Quebec-based Civil War re-enactment group made in 2017 when it erected a granite monument near Cornwall, Ont., to the Canadians who fought during that time. The Grays and Blues of Montreal go to great lengths on their website and in interviews to distance themselves from the vicious political and social debates that rage on.

The group “unequivocally condemns any individual or group which perpetuates inequality and hate according to race, gender or creed. Moreover, we most fervently condemn any acts of violence whatsoever, whether physical or verbal.” Its mission is “the promotion of the understanding of the role of the common soldier of the U.S. Civil War, more specifically from the Canadian point of view.”

Whether you can truly separate the experiences of the common soldiers from the context of the time is not entirely clear. What you can do is try to understand, if at all possible, their motivations.

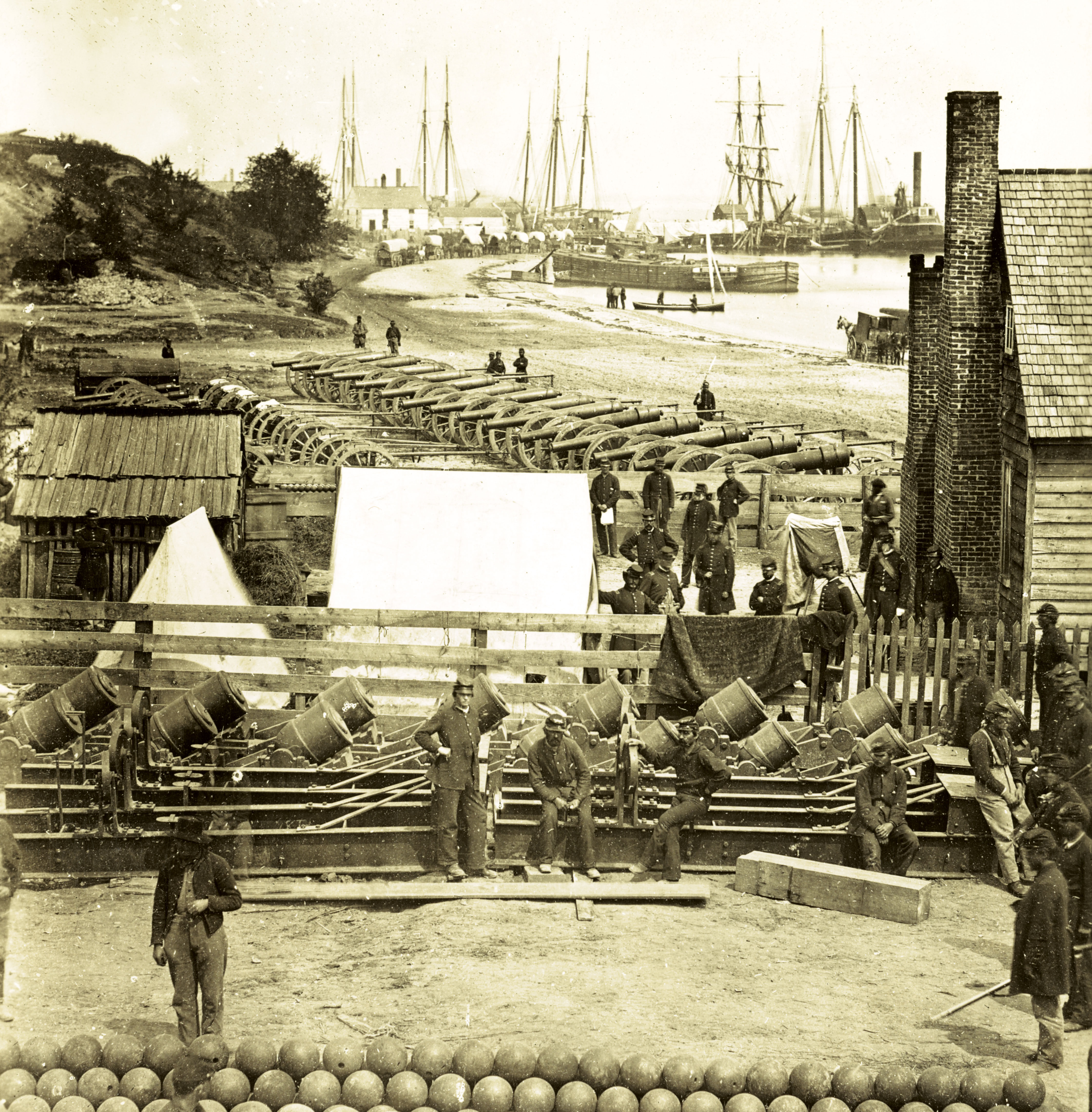

A stockpile of cannonballs, mortars and other artillery weapons in Yorktown, Virginia, in May 1862. [Library of Congress/LC-DIG-ppmsca-33296]

In the case of my great-great-grandfather, if his later writing is any indication, I suspect he volunteered out of a sense of obligation, more than an attempt to make a great moral statement against the evils of slavery.

As a doctor and humanitarian, he would no doubt have had his views on the subject, but overwhelmingly he seemed to believe he simply could not sit on the sidelines while his birth country was being torn asunder.

Interestingly, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center, among Confederate memorials still standing is the Fort Blakely Soldiers and Sailors Monument. Made up of two stone markers, it represents the Alabama and Missouri regiments that fought the battle of nearby Spanish Fort in April 1865. This monument, erected by the Mobile Bay District United Daughters of the Confederacy, is a short distance from where USS Milwaukee was sunk. They were dedicated in 2010.

The past, it seems, is still alive.

Advertisement