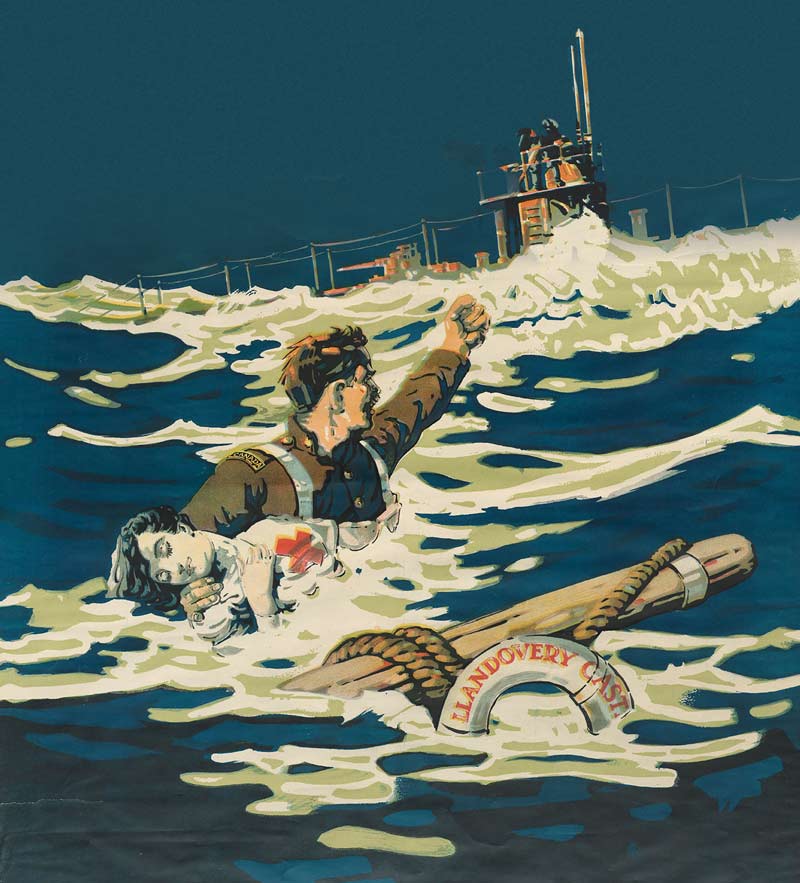

The artwork from a Victory Bonds poster (opposite) depicts the Llandovery Castle’s infamous sinking. [Nova Scotia Archives/Wikimedia]

Canadian hospital ship Llandovery Castle was approaching the coast of Ireland on the evening of June 27, 1918, when a torpedo from a German U-boat exploded on its port side.

The vessel was travelling from Halifax to England to bring ill and injured Canadian servicemen back home to recuperate. Since a return voyage was planned, Llandovery Castle wasn’t transporting any patients when it was hit. But there were still more than 250 people on board: a British crew and 94 members of the Canadian Army Medical Corps (CAMC).

The ship’s forward momentum intensified flooding through the hole left by the blast. Captain Edward Sylvester rang the engine room to stop, then reverse the engines, but there was no response—the men in that section were either dead or incapacitated. The 152-metre vessel kept plowing ahead, even as it rapidly sank. Telegraph equipment in the Marconi room had also been damaged in the blast, so a distress message couldn’t be sent. Sylvester gave the order to launch lifeboats.

All 14 Canadian nursing sisters aboard, including Gladys Sare, died. [Maurice Randall/IWM]

Under the Hague Conventions—prewar treaties that tried to regulate combat—hospital ships could be stopped and searched, but weren’t to be attacked. The vessels were to be painted white with green horizontal stripes interspersed with red crosses and be brightly lit at night so they could be identified. And they were not to carry armed soldiers, munitions or weaponry.

Llandovery Castle was abiding by these strictures, but U-86 commander Helmut Patzig didn’t care. His crew would later testify they knew their target was a hospital ship from its lights, but Patzig attacked it nonetheless.

In 1917, the German Imperial Admiralty had authorized its U-boat fleet to strike all Allied vessels in the Mediterranean Sea and a stretch of water from the English Channel to the North Sea, including hospital ships, which it alleged were smuggling weapons and soldiers. Llandovery Castle wasn’t in either location, but no matter.

CAMC staff and the ship’s crew desperately tried to launch lifeboats, a difficult task given the ship’s forward movement. One lifeboat, with 14 nursing sisters aboard capsized, and all drowned. Only a few of the boats got off before the ship disappeared underwater, minutes after being hit.

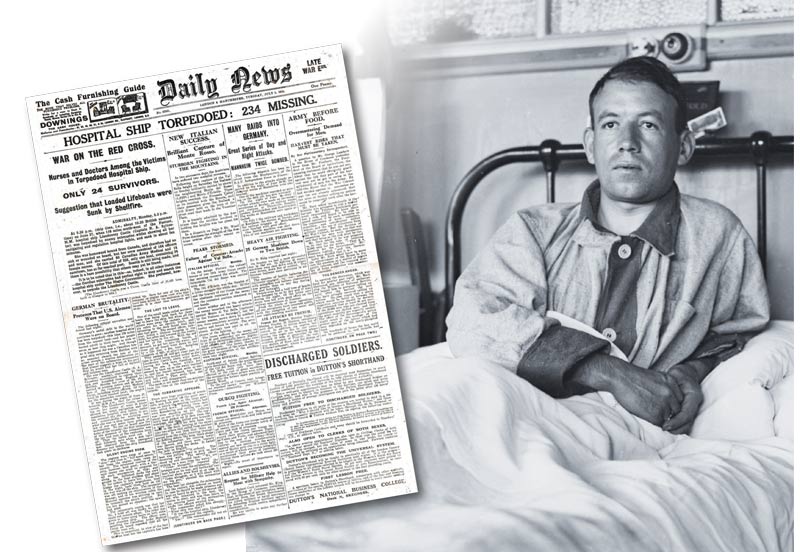

Germans sunk the hospital ship despite its clear markings. [McGill University Archives/PR015452]

The submarine surfaced and approached the lifeboats. An English-speaking German crew member ordered some of the survivors onto the U-boat, one at a time, to be interrogated. Major Thomas Lyon of the CAMC fell awkwardly on the steel deck of the U-boat after leaping from his lifeboat. He broke his foot in the process.

“You are an American flight officer,” accused the English-speaking submariner.

“No. We never carried anything but patients,” replied Lyon, wincing in pain.

The other survivors said the same thing: contrary to Patzig’s suspicions, Llandovery Castle wasn’t transporting pilots or munitions. Eventually, U-86’s commander conceded that the ship hadn’t been doing anything illicit. The attack was unjustifiable, which meant Patzig had committed a serious breach of Hague rules.

Patzig ended the interrogations, sent most of his men below deck and returned the survivors to their lifeboats. Then, with the help of Lieutenants John Boldt and Ludwig Dithmar, he directed a gunner to shell the boats with the sub’s 10.5cm deck gun. Patzig seemed determined to kill all the witnesses to his war crime.

A single lifeboat, containing six CAMC personnel and 18 British crew members, including Lyon and Captain Sylvester, escaped the massacre. They were rescued two days later by a British destroyer on patrol. News of the attack, based on survivor testimony, caused a global furor.

“Hospital Ship Willfully Sunk” blared the front page of the San Francisco Examiner.

“There is something peculiarly infamous in a stealthy attack on a hospital ship. The vessel is not armed. It carried no fighting men. It is helpless…the inhuman monster who commanded the submarine knew exactly what he was doing,” The Philadelphia Inquirer argued in an editorial.

Speaking at the 1918 Imperial War Conference in London, England, Prime Minister Robert Borden deplored “the sinking of our hospital ship [and] the murder of nurses and doctors.”

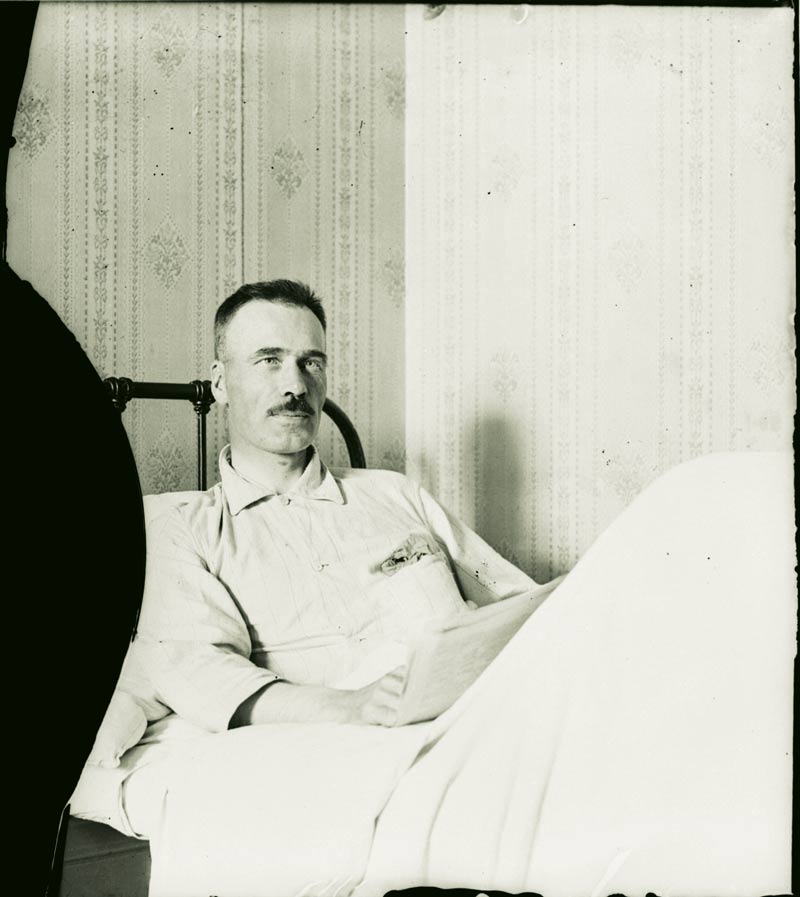

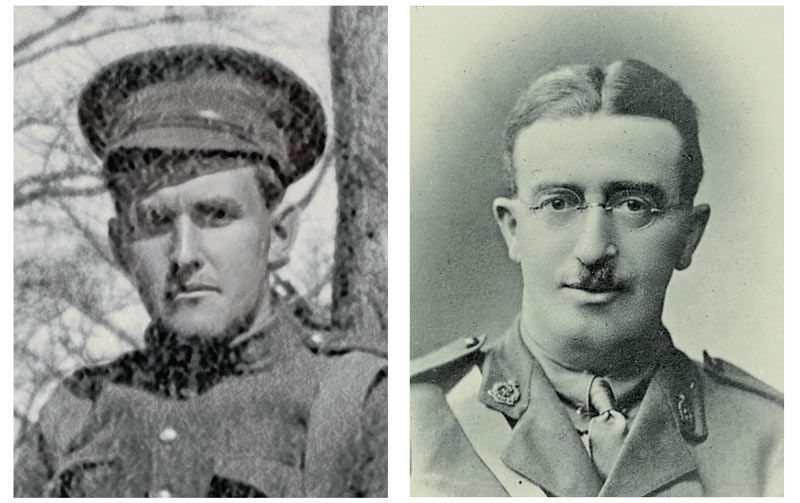

Major Thomas Lyon and Sergeant Arthur Knight of the Canadian Medical Army Corps were two of just 24 survivors. [DND/LAC/3218510]

“A wild beast is at large, and it is no use arguing or attempting to reason with it. We must destroy it. We must set our teeth until this end is achieved,” added British MP Bonar Law during the International Parliamentary Conference in the U.K.

In a grim irony given its role as a healing ship, “Remember the Llandovery Castle!” became the battle cry of Canadian soldiers at the Battle of Amiens in August 1918. The bloody campaign helped lead to the Armistice in November, followed by the Treaty of Versailles, which officially ended the war in June 1919. Among other provisions, the agreement demanded that German leaders be tried for war crimes.

Major Thomas Lyon and Sergeant Arthur Knight of the Canadian Medical Army Corps were two of just 24 survivors.[John Frost Newspapers/Alamy/2E5HP11; DND/LAC/PA-007471]

The postwar government in Berlin wasn’t eager to hand over German citizens for trials with Allied tribunals, so it suggested a compromise. War crime trials could be held at the German Imperial Court of Justice (Reichsgericht) in Leipzig. The Allies could provide lists of suspects, witnesses and evidence, while Germany handled prosecutions and defence. An agreement was reached, and the Leipzig war crimes trials commenced in early 1921. Only a handful of cases—one of which involved Llandovery Castle—were heard.

Commander Patzig couldn’t be tracked down, so German authorities abruptly arrested Boldt and Dithmar and built a case around them instead. When their trial opened on July 12, 1921, the lieutenants were unrepentant.

“I obeyed my commander. His orders were law. I am not guilty,” testified Boldt.

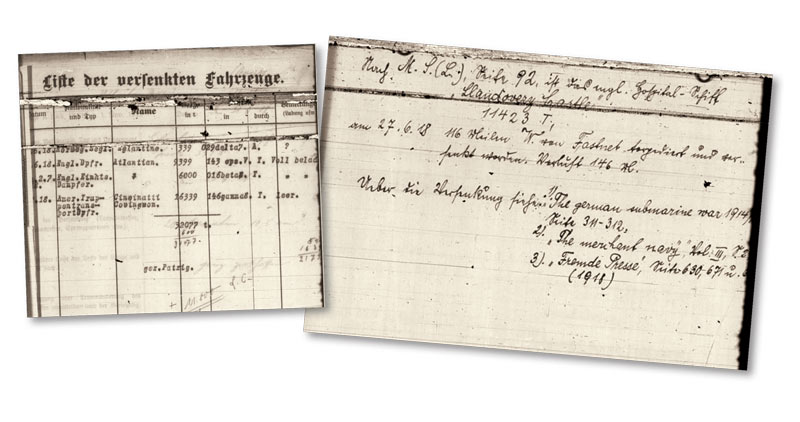

The Leipzig war crimes trials heard the case of Llandovery Castle. [Gallica Digital Library/Wikimedia]

Llandovery Castle survivors were among the witnesses for the prosecution. Captain Sylvester had died of heart failure a year earlier, but Major Lyon was available. Boldt and Dithmar’s trial had been so hastily arranged, however, that Lyon had only a few days to rush from his home in Vancouver to Leipzig.

After travelling thousands of miles, Lyon “furnished the sensation of the trial by immediately abusing the infamous and cowardly methods used by the submarine commander. He vehemently attacked Captain Patzig for the sinking of the helpless ship,” reported the Vancouver Sun.

The German court pondered the testimony and evidence entered, then delivered its verdict four days after the trial started. While largely ignoring the initial torpedo attack, the justices convicted Boldt and Dithmar for their role in the attempted murder of survivors. In its ruling, the court set two precedents: war crimes should be judged by international standards and following orders is not a defence for committing illegal acts in wartime.

“The firing on the boats was an offence against the law of nations. In war on land the killing of unarmed enemies is not allowed…similarly in war at sea, the killing of shipwrecked people, who have taken refuge in lifeboats, is forbidden,” said the judges.

While Patzig directed the shelling, his order did “not free the accused from guilt,” the judgement continued. “The subordinate obeying such an order is liable to punishment, if it was known to him that the order of the superior involved the infringement of civil or military law.”

Boldt and Dithmar were sentenced to four years apiece, but quickly escaped from jail with the help of supporters. Due in part to this dismal outcome, the Leipzig trials were regarded as a failure and Llandovery Castle was largely forgotten.

The war diary of U-86 commander Helmut Patzig makes no mention of the U-boat’s attack on Llandovery Castle.[National Archives and Records Administration, Microfilm Publication M1743]

By the 1920s, the Canadian public wanted to move on from the slaughter of the Great War. While victories at Vimy Ridge and Passchendaele were lauded, there seemed little glory or gain from the Llandovery Castle sinking. The Halifax Explosion, which resulted in an outpouring of assistance, became the wartime tragedy commemorated by Canadians.

Timing and cynicism also contributed to this cultural amnesia. Llandovery Castle was sunk late in the war, giving the Allies only a few months to use the atrocity as propaganda. By contrast, Lusitania, a British passenger liner with a contingent of American passengers, was torpedoed by a U-boat in May 1915. The Allies had years to depict its sinking and the deaths of nearly 1,200 as an example of German barbarity.

After the war, the public learned that the Allies had also engaged in acts of dubious morality. While they had condemned Germany’s policy of unrestricted submarine warfare in which merchant ships were sunk without warning, the Royal Navy had blockaded German ports to prevent vessels from delivering everyday supplies, resulting in mass starvation. And, despite furious denials during the war, Lusitania had indeed been carrying materiel.

The controversial 1930 Canadian antiwar novella Generals Die in Bed by Charles Yale Harrison implied that Llandovery Castle wasn’t playing by the rules either. In the story, an officer graphically recounts the Llandovery Castle sinking to motivate his troops. At the book’s end, however, the narrator discovers that Llandovery Castle was also transporting war munitions.

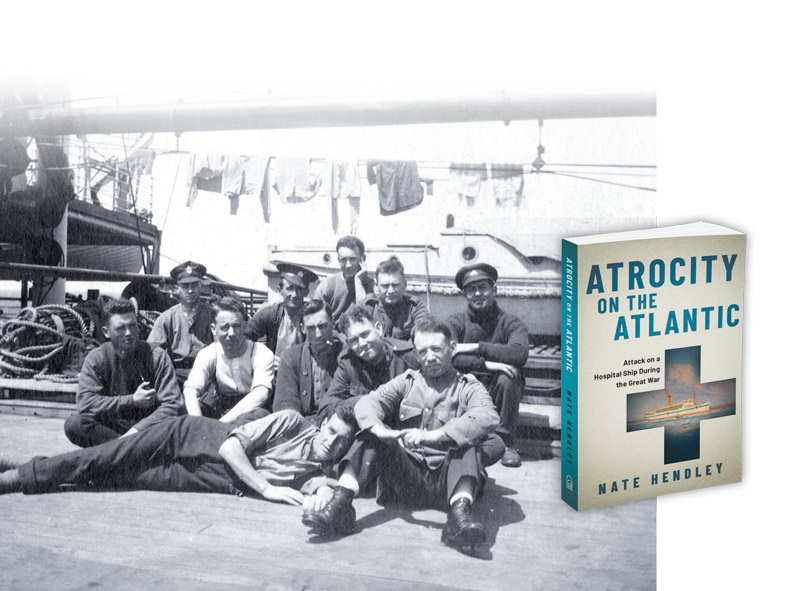

Private William Pilot (left, with other crew aboard the ship) survived the ordeal, though Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Macdonald (immediate left), commander of the Canadian Army Medical Corps, did not.[ CWM/20070096-027]

There is no evidence this was true; the ship was inspected twice before leaving Halifax on its final journey and subsequent reports didn’t indicate anything amiss. On an earlier voyage, a patient’s attempt to smuggle souvenir swords on board caused an administrative uproar.

Still, the novel helped obfuscate already dimming memories of the Llandovery Castle tragedy.

In the 1940s, however, prosecutors started taking careful note of the Leipzig verdict as they prepared for a new round of war crimes trials. State Prosecutor Colonel N.K. Dunayev referenced the Llandovery Castle case at the Kharkov trial—the first war crimes proceeding against Nazis. Held in December 1943 in what is now Kharkiv, Ukraine, the trial pitted three German defendants and a collaborator against a Soviet military tribunal. Charged with massacring civilians and prisoners, the accused insisted they were just following orders.

Canadian nursing sisters Anna Stamers, Christina Campbell, Rena McLean, Jessie McDiarmid and Carola Douglas all drowned in the sinking.[Antigonish Heritage Museum]

When it was his turn to speak, Dunayev cited “the atrocious sinking of the British hospital ship Llandovery Castle” and subsequent trial.

Boldt and Dithmar had also been following orders, but the Leipzig court made clear “that did not absolve them of responsibility, as there could be no doubt that the accused realized the dishonourable and criminal nature of their commander’s intention,” said the colonel.

Despite misidentifying Llandovery Castle as British, Dunayev’s point stood, and the four defendants were convicted and hanged.

The constitution of the International Military Tribunal, which was created to prosecute the Axis leadership after the Second World War, specifically

disallowed obedience to superior orders as a defence, except in mitigation of sentencing.

The same principle guided the Peleus trial in Hamburg, Germany, in the fall of 1945. Held before a British military court, this eerily familiar case involved crew members and the commander of U-852. They were accused of trying to gun down survivors of Peleus, a steamship the sub had torpedoed. The crew said they were acting under orders, but the court rejected this defence and they were convicted.

[CWM/20070096-010; IWM/Wikimedia (5)]

“Much reliance was placed in the Peleus case, both by the Prosecutor and by the Judge Advocate, on the decision of the German Supreme Court in the case of the hospital ship ‘Llandovery Castle,’ delivered in 1921,” stated a United Nations War Crimes Commission summary.

SS death squad members at the 1947-1948 Einsatzgruppen trial in Nuremberg also cited superior orders to deny culpability for mass murder. Brigadier General Telford Taylor, chief counsel for the prosecution of the presiding American military court, quashed this defence.

Soldiers don’t have to obey “palpably criminal” orders, a principle “concisely set forth in the decision of the Supreme Court at Leipzig in the Llandovery Castle case,” stated Taylor.

The SS men were all found guilty and sentenced to death or prison terms.

The Geneva Convention of 1949 consolidated and strengthened previous treaties governing wartime conduct. Once again, attacks on hospital ships were forbidden.

The principles established at Leipzig helped shape the legal foundation of the International Criminal Court, empowered in 2002 to prosecute war criminals around the world. The court rejects the superior orders defence and views war crimes as violations of international norms and law.

It might have been some solace to those lost on Llandovery Castle that their fate would lead to the universal legal axiom that people who commit war crimes should be held responsible for their actions.

Advertisement