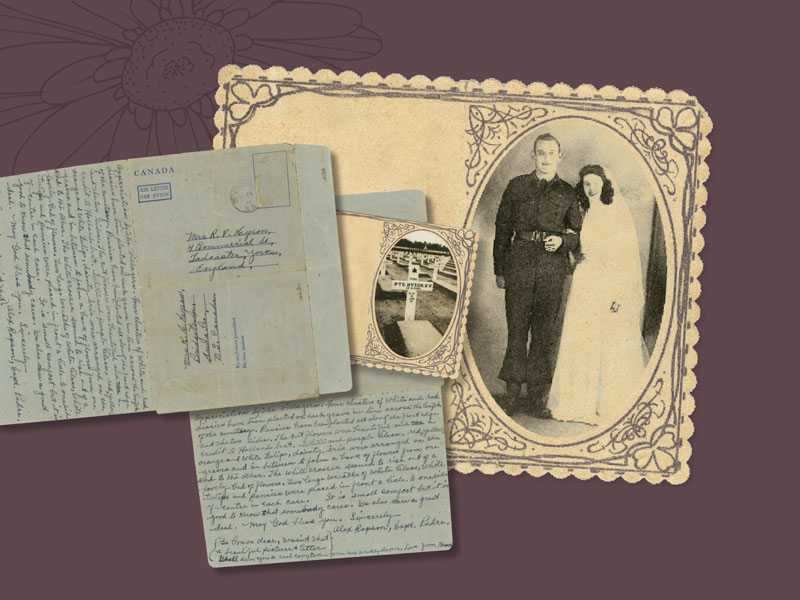

Wedding photo of Ronald and Kathleen Hyson, Nov. 3, 1944. Ronald was killed in action on April 16, 1945. [Courtesy Stewart Hyson]

May 8, 2025, looms significantly on the horizon as the 80th anniversary of the official end of the Second World War in Europe. Not necessarily a joyful celebratory occasion, but more of a time to reflect on the deadliest conflict in human history. A time to remember those who perished during that, and other, conflicts.

To die during a military campaign is a real possibility faced by soldiers, not to mention a consequence of warfare for civilians, too. However, when it comes to casualties of war finding a final resting place—to rest in peace—there’s no assurance.

The term closure is now commonly used to refer to the process whereby the deceased are treated with care and dignity in line with social customs. During the 2001-2021 war in Afghanistan, for example, it became customary to repatriate the remains of Canadians killed in action for burial, to allow family members and close friends to have a measure of closure.

This practice wasn’t used during earlier conflicts on foreign soil, as is evident by the presence of numerous war cemeteries around the world established over the years by the Canadian government and the governments of other countries. While the personal element of closure may have been absent in the past, the essence of it, caring and recognition, was still present, albeit in a different way.

After my birth father Ronald V. Hyson was killed during the Second World War in April 1945, he was twice buried temporarily before he came to rest at last in the Netherlands’ Holten Canadian War Cemetery. His situation is probably similar to thousands of other Canadian soldiers who died overseas and sheds a light on a little-known reality.

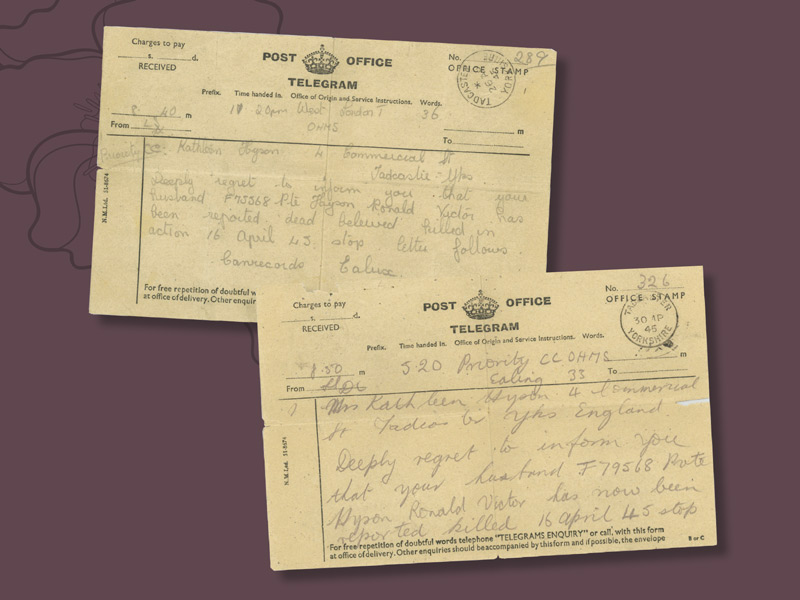

In a way, the story starts with my mother’s receipt of the dreaded telegram. A telegram delivered to an Allied home during WW II usually foretold of a soldier that was dead, missing or who had been taken prisoner. Wives and families receiving one were so aware of what they typically meant, there was little need to read them.

Still, the hand-written message she received on April 26, 1945, came as a shock.

“Deeply regret to inform you that your husband F75568 Pte Hyson Ronald Victor has been reported dead believed killed in action 16 April 45.”

Short, to the point, but far from sweet. It was a wartime ritual repeated so many times each day that there was little room for any personal touch.

My mother looked at this telegram, and looked again, with the disbelief that only such a harsh message can induce. More importantly, she detected that something was wrong, although it wasn’t immediately apparent what the problem was.

Ron, a Canadian soldier serving with the 1st Battalion, 48th Highlanders of Canada, and my mother Kathleen, a Yorkshire lass, had been married in England on Nov. 3, 1944. Afterward, he returned to the front. It was obviously difficult for my mom to face the fact that she was now a widow after only five and a half months of marriage, but she still had a nagging feeling that there was something mistaken in the telegram.

Finally, it hit her. The service number wasn’t Ron’s. She knew it by heart. So, possibly the whole message was an error?

A second telegram arrived four days later, but without the word “believed” and with Ron’s correct service number (F79568). It’s not known how the service number error was made with the first telegram. Regardless, the subsequent message was clear: there was no longer any doubt that Ron had been killed in action.

Being five months pregnant, my mother was riled up enough to take pen in hand and contact Ron’s immediate superiors. It was her way of seeking closure.

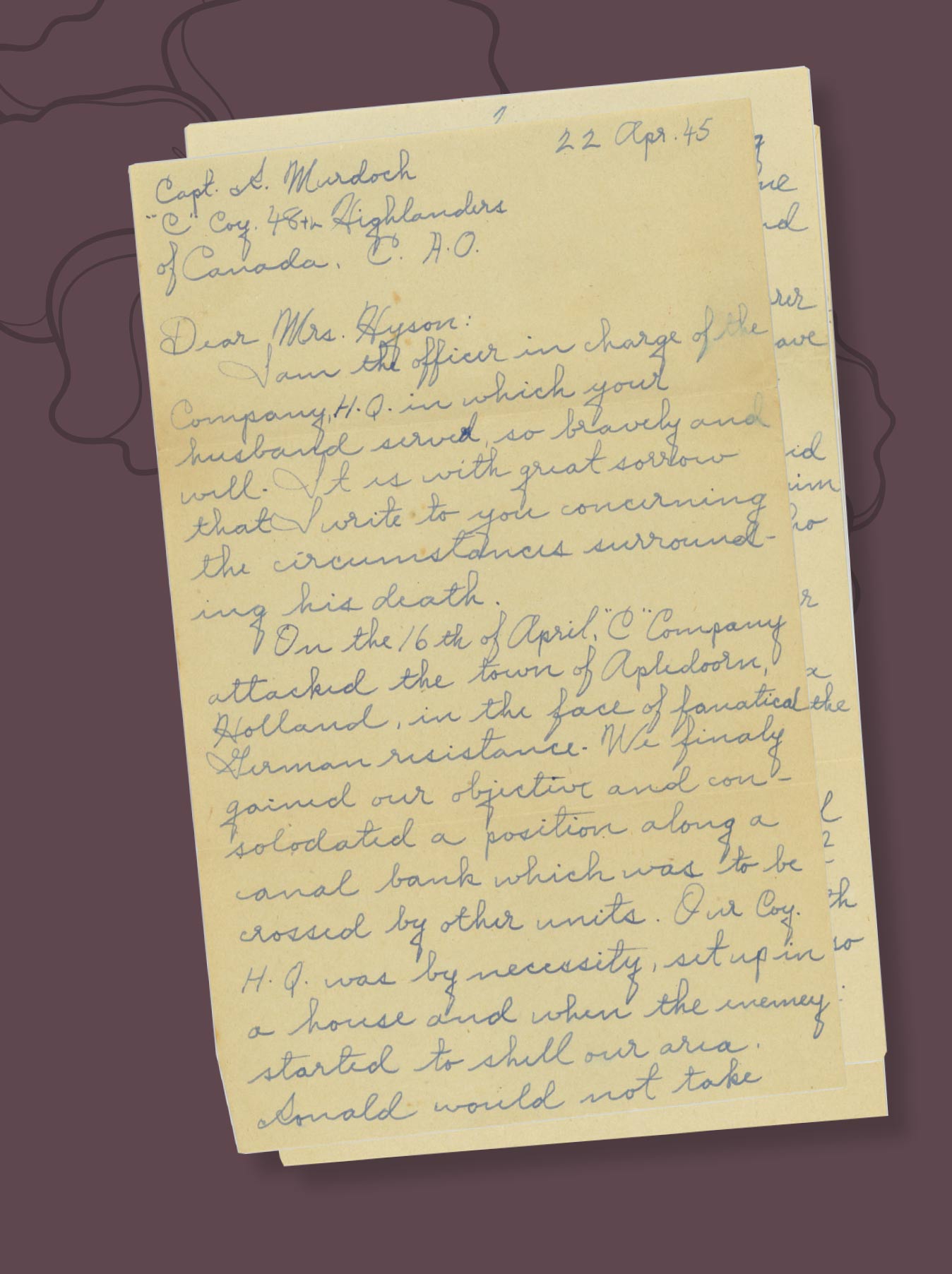

She received hand-written letters back from Ron’s captain, Robert Murdoch of ‘C’ Company, 48th Highlanders of Canada, and from padre Captain Alex Rapson that provided her some clarity. They detailed how Ron had been killed, provided information about his two temporary burials and offered some words of comfort.

During the Battle of Apeldoorn, ‘C’ Company had achieved its objective of crossing the IJssel river to reach the Dutch village of Wilp. There it established a headquarters in a farmhouse. When it was hit by shellfire a short time later, Ron was a casualty—unconscious and probably dead by the time stretcher-bearers took him to a nearby regimental aid post to be seen by a doctor who made the final call.

Padre Rapson arranged for Ron and other fallen soldiers to be taken to what Captain Murdoch described as “a pleasant and quiet spot” as their first temporary resting place until the end of the battle. Once the hostilities ceased in the area, Rapson conducted a formal service on April 26, 1945, for the 19 members of the 48th Highlanders who had died in the Wilp area.

This formal burial (albeit second temporary) was on top of a dike that’s a few metres away from a street that runs through the village of Wilp. Rapson’s vivid description of the ceremony brings it to life. Each grave was marked by a small white cross with the whole area immersed in a rich display of daisies, pansies, tulips and irises of diverse colours (red, purple, yellow, orange and white)—the crosses, he wrote, “seemed to rise out of a lovely bed of flowers.”

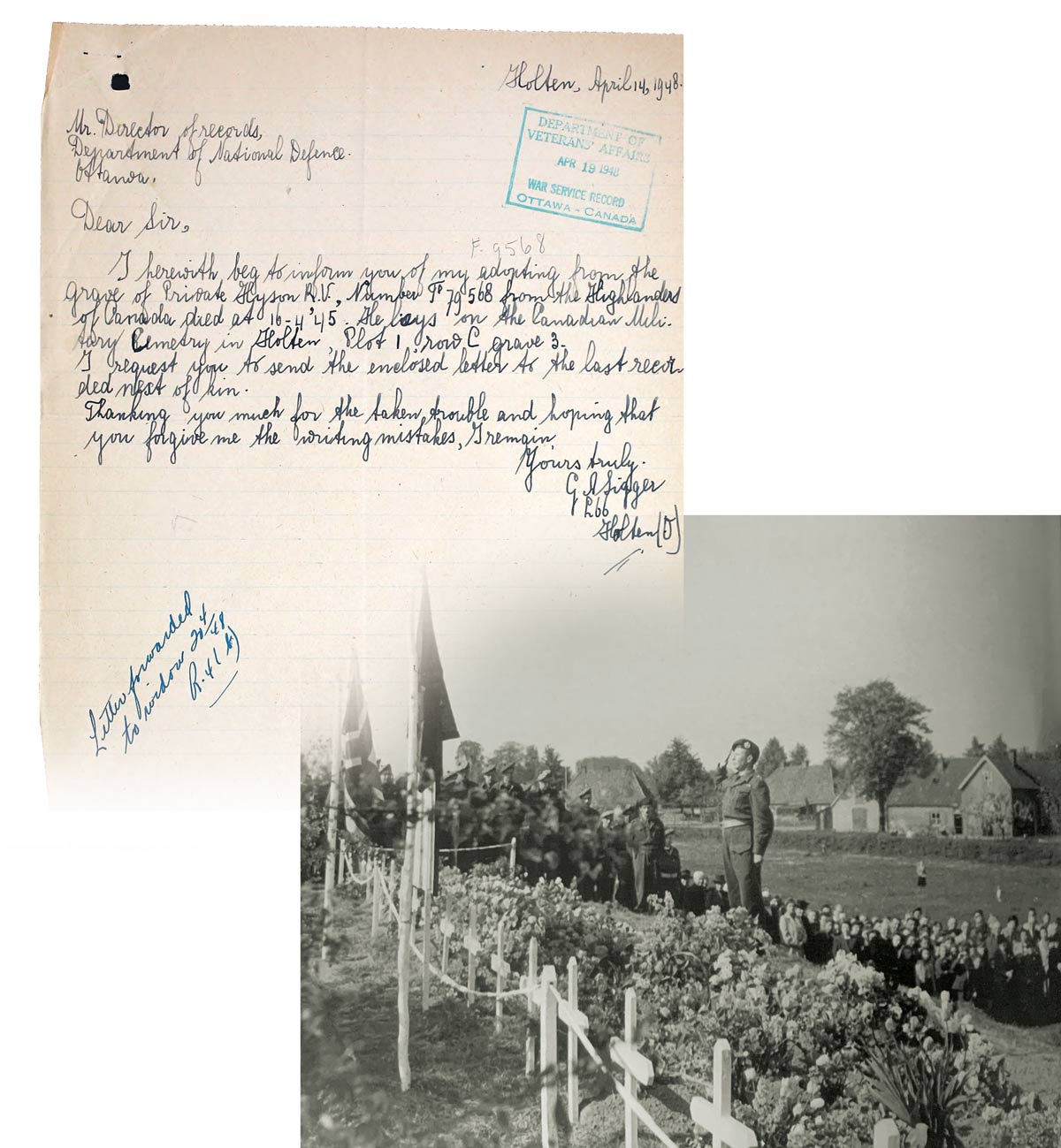

Dutch citizen Bennie Sigger writes to Kathleen after “adopting” her husband’s grave. Members of The 48th Highlanders of Canada honour their comrades, including Ronald, killed near, and originally buried in, Wilp, Netherlands, as locals look on. [Family of Volunteers: An Illustrated History of The 48th Highlanders of Canada]

After the war, the remains of deceased soldiers were eventually collected from small local graves across Europe, such as the one at Wilp, and transferred to centralized military cemeteries for final burials. It was a respectful way to treat those who had died.

The men buried temporarily in Wilp, and others killed in the nearby area around Apeldoorn, were moved to the Holten Canadian Military Cemetery. A central Cross of Sacrifice there is surrounded by the remains of 1,382 personnel.

When it first opened in 1948, the grave markers were white wooden crosses, which included the soldier’s name, regiment and date of death. Each plot was rectangular to accommodate the full length of a soldier’s body with the soil covering it rising a few centimetres above the surrounding ground. The top of each grave was covered by what looks to be a layer of beach-like sand.

A black-and-white photo of Ron’s plot was sent to my mother by Veterans Affairs on June, 24, 1948; no doubt, similar images were sent to the nearest next of kin of all buried soldiers.

Today, inscribed headstones have replaced the wooden crosses. A carpet of turf now grows over the walking paths around the headstones, too. Flowers may be deposited by visitors and caretakers on a small patch of soil at the base of each headstone. Special ceremonies are held on veteran-related occasions at the Holten cemetery, and annually on the Netherlands’ Liberation Day (May 5) and on Christmas Eve, when each grave is lit by a candle.

A little over a month before receiving the plot picture from Veterans Affairs, my mother got a letter from a Dutch boy named Bennie Sigger. Out of gratitude to the Canadians who had helped liberate them, the residents of Holten had each volunteered to “adopt” a soldier’s grave to look after it. Sigger had adopted Ron’s plot. Many letters, and now emails, have continued to maintain this special link between Sigger and my family.

The 48th Highlanders, the federal government and people of the Netherlands have had their moments of closure with the soldiers who served them. But what about my mother? She received partial closure over the years from the occasional correspondence, but it wasn’t until visiting Ron’s grave in 1994 that she finally laid him to rest.

Advertisement