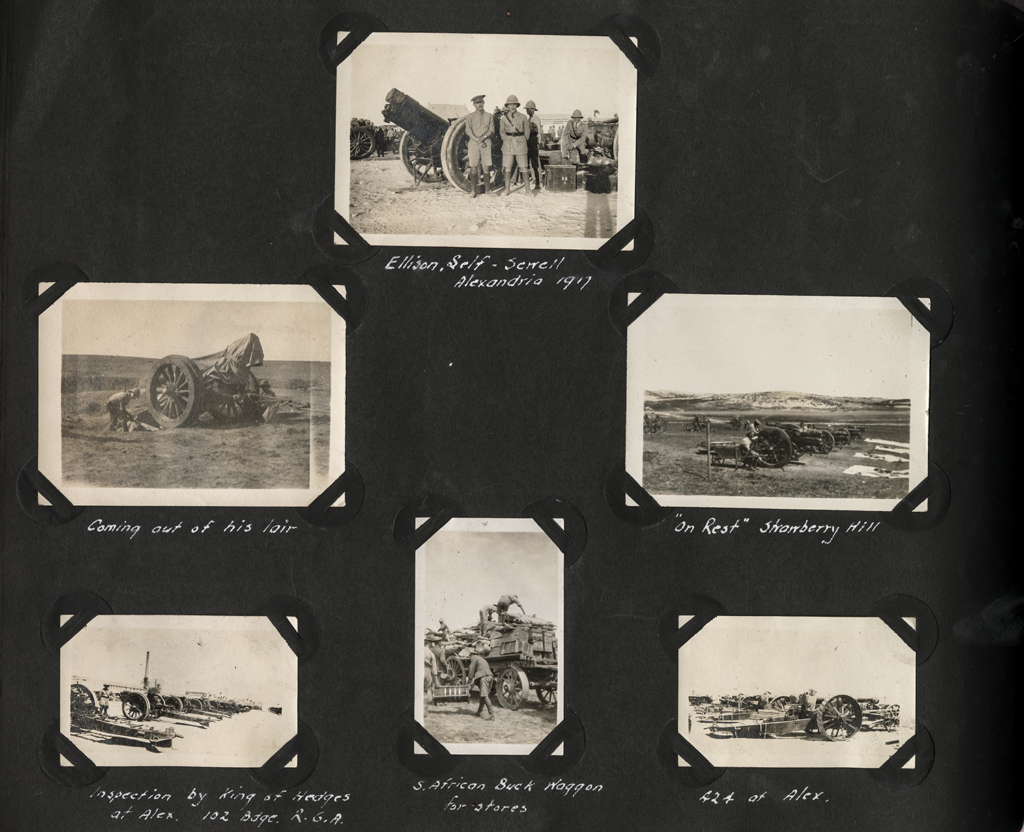

A time-worn album of sepia-toned photographs and a file of yellowed handwritten intelligence summaries tell the wartime backstory of a peacetime storyteller, my Great-Uncle Harvey.

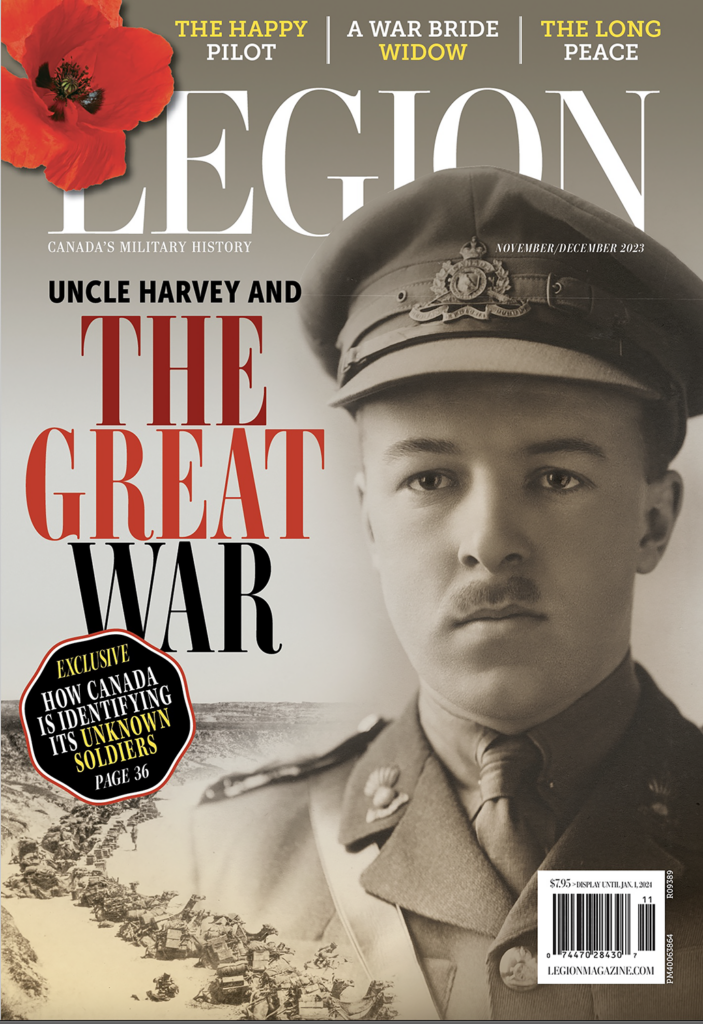

The First World War-era pictures appear with my cover feature in the November-December 2023 issue of Legion Magazine.

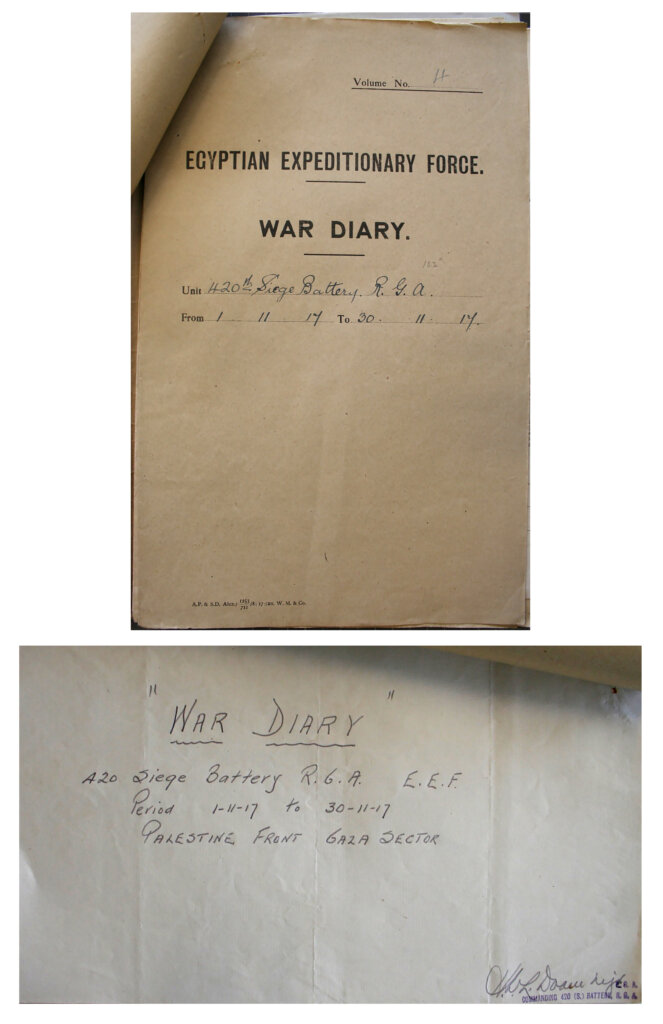

The intel reports, or war diaries, most of which are buried in the recesses of Britain’s National Archives, were kindly unearthed and photographed for me by Paul O’Rorke, a Royal Garrison Artillery researcher in Berkshire, England.

Each page of the monthly reports—handwritten in pencil or pen—is signed by H.W.L. Doane, Major, OC (officer commanding), 420 Siege Battery, RGA, EEF (Egyptian Expeditionary Force).

On secondment to the British artillery unit and dispatched to the far reaches of the war to join the fight against the German-allied Ottoman Empire (aka“Johnny Turk”), the 25-year-old from Halifax must have been admonished for his handwriting because he resorts to exquisitely clear print from cursive after his first few field reports.

They commence at Codford, England, in August 1917 and work their way through Alexandria and on to the Palestine front at Gaza before the unit returns to Egypt in April 1918. No. 420 headed to France, and the Western Front, in May.

A wartime photograph of a pith-helmeted 420 Siege Battery, RGA, with its officer commanding, Major Harvey William Lawrence Doane of Halifax, seated at centre behind local aide, in white shirt. [Mary Doane/Doane Family Archive/Scan by Shoebox Studio Ottawa]

British forces suffered almost 4,000 casualties during the first Battle of Gaza in March; the Ottomans took 2,000.

Known today as the focal point of fighting between Hamas and Israel, Gaza with its Ottoman fort was a defensive stronghold in southern Palestine in 1917, more than three decades before Israel declared independence and opened its newly proclaimed borders to survivors of the Nazi Holocaust.

The territory was strategically important because of its water wells. Water was a scarce commodity in the Middle Eastern deserts and an important Allied resource due to their large numbers of mounted troops and horses. Camels, too, were integral to both the supply chain, and the tribal Arab fighters who were staging an uprising against the Ottomans.

An important stepping-stone in the Allied drive to Jerusalem, Gaza had cost the British dearly in two battles before the legendary Field Marshal Edmund Allenby took over command of the EEF about the time 420 arrived in Egypt.

British forces suffered almost 4,000 casualties during the first Battle of Gaza in March; the Ottomans took 2,000. The second battle, in April, was an unmitigated disaster, costing the Brits nearly 6,500 casualties to the Ottomans’ 2,000.

The main battle in the third and decisive action would take place on Nov. 1-2.

“Never during my service overseas did I see such loyalty as was displayed by the soldiers under Lord Allenby’s command.”

In a 1926 newspaper interview, Harvey said the Middle East climate hit his troops hard when they first arrived.

“For the first few days, we were all pretty sick but after we became acclimatized we got along fine,” he said, citing Allenby’s leadership as an inspiration to all.

“Never during my service overseas did I see such loyalty as was displayed by the soldiers under Lord Allenby’s command,” he said. “They actually adored him.

“Nothing that he asked was too hard for them to execute, for he never asked anything for which there was not a good reason.”

Harvey’s battery moved into Gaza in late September, about the time his most illustrious contemporary, a berobed T.E. Lawrence, was leading the Arab revolt in an attack on a troop train just south of Mudawwara, Jordan’s most southerly settlement. They destroyed a locomotive and killed some 70 Turkish soldiers.

The famous victory at the Red Sea port of Aqaba, depicted in the David Lean film Lawrence of Arabia, had taken place in July.

RGA batteries such as Harvey’s consisted of two sections, left and right. Each two-gun section was divided into two subsections of one gun each. Later in the war, another section was often added to make six-gun batteries.

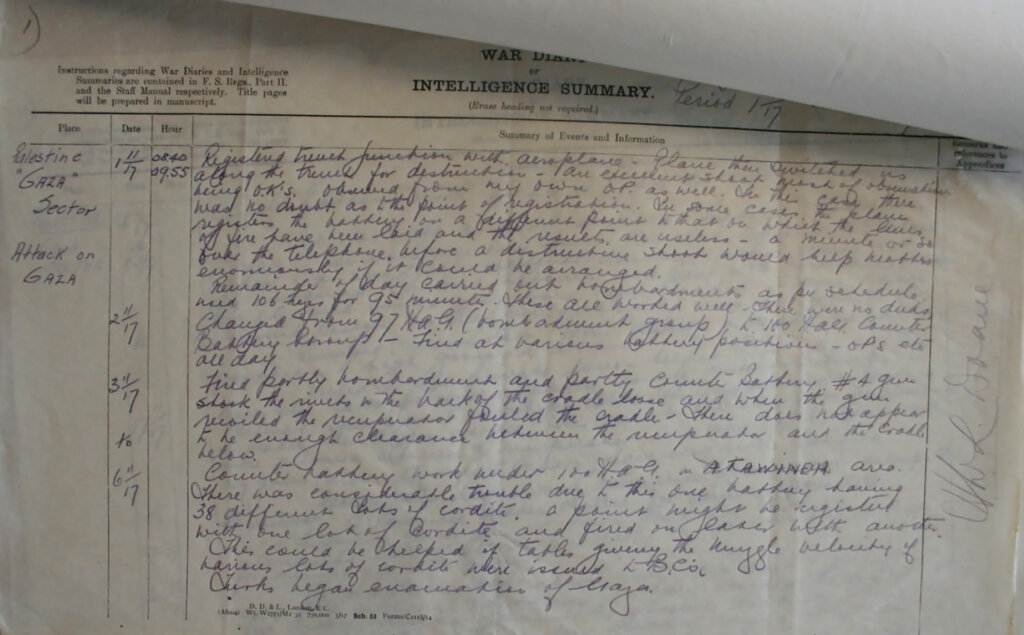

They calibrated their weapons with the help of an “aeroplane” after setting up their position and building dugouts at the east end of the British line on the Gaza Front.

A pictorial and feature story on Uncle Harvey fronts the November-December edition of Legion Magazine.

Mobile artillery was still in its infancy, and issues were constantly arising.

They fired their first shots in anger at Deir al Balah on Oct. 9.

“Fired for first time from battery position at enemy dugout 23 rounds,” wrote Harvey. “Nos 1 and 2 guns had not sufficient packing for spade and shooting was poor compared to 3 and 4.

“Fired night bombardment on same dugout 12 rounds 1 salvo and 2 rounds.”

The spade was a large piece of flat medal projecting downward at the very back of the gun’s apparatus. It was dug into the earth and covered with packing to prevent the weapon from moving backward or forward, or slewing sideways, with recoil.

“In this case not enough earth…was packed tight enough, or weighty bags of sand packing prevented the gun from moving and thus it deviated from the original calibration of the gun (line of fire),” explained O’Rorke.

“Therefore, each and every prior fall of shot could not be relied upon to get a better fix on the target for the next round of firing, the Howitzer probably having to be recalibrated each time.”

He noted, too, that flaws existed in “airplane cooperation with artillery.”

The battery would go on to use aircraft to register targets within each gun’s arc of fire, Alī al Minţār—an 87-metre-high feature in Gaza—and a trench junction among them.

“Plane then switched us along the trench for destruction,” Harvey wrote on the first day of the final battle. “An excellent shoot.”

Indeed, the shooting improved in fits and starts. A civil engineer back home, Harvey’s reports are laced with observations and solutions to a string of technical bugs bedeviling the British gunners. Mobile artillery was still in its infancy, and issues were constantly arising and being addressed on the fly.

“#4 gun shook the rivets in the hack of the cradle loose and when the gun recoiled the recuperator fouled the cradle,” he wrote, referencing the hydraulic recoil mechanism of an artillery gun.

“There does not appear to be enough clearance between the recuperator and the cradle below.”

Harvey would later send one of his guns to a British army workshop at Deir al Balah to find a solution to the problem. The village, 16 kilometres east of the Egyptian border and 20 kilometres southwest of present-day Gaza, was a railhead and remains the site of a multinational war cemetery.

“All my guns (2 Coventry and 2 Vickers) have very little clearance.”

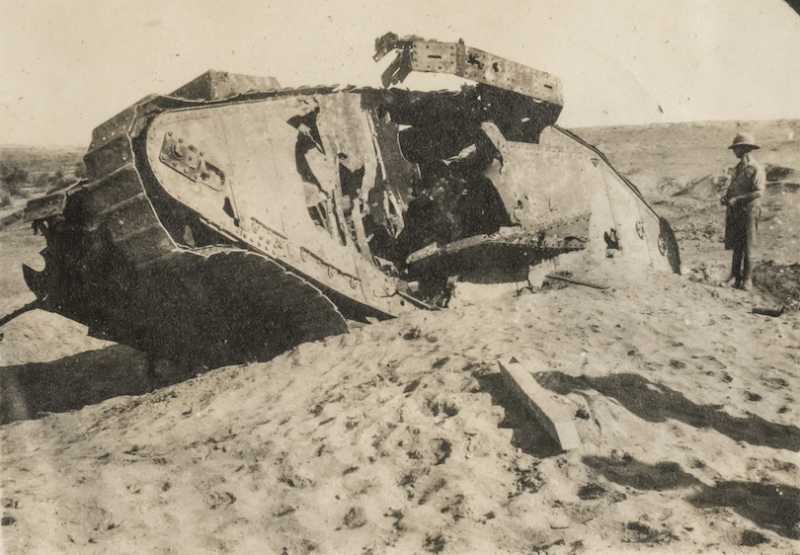

A destroyed tank lies inert in the Palestinian desert. [Mary Doane/Doane Family Archive/Scan by Shoebox Studio Ottawa]

Harvey’s notes show him, too, as a humanitarian and leader.

Another issue arose with inconsistencies in the lots of cordite they were using as a propellant during the decisive attack on Gaza.

The smokeless cordite contained a mix of nitroglycerine, acetone, gun cotton and Vaseline and was a contentious adaptation of a non-gunpowder propellant invented by Alfred Nobel (the founder of the Nobel Prizes sued the British developers over an alleged patent infringement).

“There was considerable trouble due to this one battery having 38 different lots of cordite,” Harvey noted. “A point [ranged target] might be registered with one lot of cordite and fired on later with another.

“This could be helped if tables giving the muzzle velocity of various lots of cordite were issued.”

He noted, too, that flaws existed in “airplane cooperation with artillery,” apparently due to the primitive wireless communications of the time, which depended on an unobstructed signal.

“In several instances I have missed the order to fire during ranging because the observer sent it while he was turning and the wireless operator could not hear it.”

As the bombardment intensified on Nov. 6, he noted that the “Turks began evacuation.” The next morning, the objective lay abandoned and undefended.

British forces suffered 2,696 casualties; the Turks are known to have buried more than 1,000 dead. Harvey and the OC of another battery visited the vacant Turkish position on Nov. 8.

“Trenches were very much knocked about,” he reported. “H.E. [high-explosive] shell appear to do very little material damage unless direct hits are obtained.

“Turkish batteries were very well concealed under trees, etc. and could only have been located in some cases by sound ranges as they were practically invisible from the air.”

Special units used “sound ranging” to determine where enemy gunfire was coming from. Technicians would set up strings of microphones—barrels of oil dug into the ground—at intervals, then use photographic film to visually record noise intensity. It was similar to how seismometers record earthquakes. Using the data and the time between when a shot was fired and when it hit, they could then triangulate where enemy artillery was located, and adjust their own guns accordingly.

A surviving sound ranging image of the last shots of the First World War at the River Moselle on the American Front was translated by the sound production company Coda to Coda for the Imperial War Museums in London. Credit: Coda to Coda/IWM

They were camped in a wadi when a heavy rain “practically washed out the dugouts…. All cookhouses etc. were moved to the top.” Stores in subsequent encampments were to be kept atop the wadis to avoid the “enormous run off” that inevitably came with sudden showers.

Rations arrived daily via “limbered waggons” (two-wheeled, horse-drawn wagons) from Belah; camels delivered water in fantasses, 12-gallon containers that looked like oversized jerry cans.

Harvey’s notes show him, too, as a humanitarian and leader attuned to the mood and disposition of his men, always on the lookout for their welfare.

“Men find their canteen a great convenince,” he noted when the fighting abated. “A small coffee dugout provides a place to sit and chat in the evening.

“The spirit and discipline of the battery has improved enormously since coming from England…. Rations are excellent.”

Harvey’s 105-year-old album is filled with hundreds of photographs from the wartime Middle East, England and France. [Mary Doane/Doane Family Archive/Scan by Shoebox Studio Ottawa]

Troops were also forbidden to buy or eat fruit brought in by locals on account of a disease outbreak.

The battery, however, was suffering from a bout of septic sores—improperly cleaned cuts, scrapes or other minor wounds contaminated by bacteria, viruses or fungi. Harvey observed “aperients [medicine], lime juice and plain food” helped solve the problem.

“If the sore is disinfected as soon as the skin is broken it is in most cases prevented from becoming septic.”

Troops were also forbidden to buy or eat fruit brought in by locals on account of a disease outbreak. And the men’s boots had become hard and dry in the Middle East climate; tallow was being used to soften them.

“If a supply of ‘dubbin’ were available it would keep the boots in much better condition and they would be more comfortable for the men,” he noted.

The battery moved up as the Allied advance progressed. Battery stores were transported on sledges towed by Holt tractors—an arrangement that once again brought out the engineer in Harvey.

“These sledges caused some trouble on account of not having deep enough runners to keep the floor above ground in soft places,” he reported. “There should be three longitudinal runners of at least one foot deep for a five ton sledge.

“The weight should be so distributed that the front tends to lift slightly; otherwise a [wall] of sand forms in front stops the tractor.”

The Gaza-to-Beersheba line subsequently collapsed and the Ottoman Seventh and Eighth armies were forced to retreat. After several battles during the pursuit, the EEF captured Jerusalem on Dec. 9, 1917.

Harvey’s photo album is bursting with pictures of the liberated old city—Arab fighters parading through the streets on horseback; Allenby himself meeting with Arab elders.His war diaries follow No. 420 through January and February 1918, when the unit was training, troops were taking leave and equipment was being serviced.

“Men are being kept in condition by going on route marches daily—also now and then a sea bathe is included. Football, tug-of-war, races, etc. are carried on each afternoon with other batteries and between subsections.

“Twenty men per day from the battery are salvaging all telephone wire left by the units which have advanced.”

Harvey would take R and R in Egypt and explore the pyramids, the Great Sphinx and other ancient sites before returning to Palestine.

The battery moved to the Sidi Bishr rest camp in Alexandria in early-May 1918. By month’s end, they would be calibrating their guns in northern France.

Advertisement