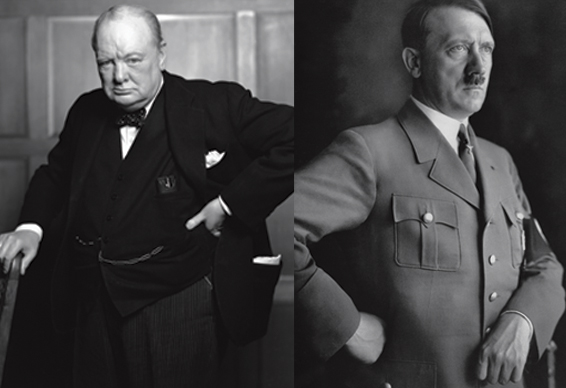

Winston Churchill and Adolph Hitler were both charismatic, demanding leaders who promised to restore order to their society after the disruption and devastation of the Great War. They were also mortal enemies with very different visions of what social order should look like.

Emnity

“If we can stand up to him, all Europe may be freed.”

—Churchill (LEFT)

“The gift Mr. Churchill possesses is the gift to lie with a pious expression on his face.”

—Hitler (RIGHT)

When Adolph Hitler came to power, Winston Churchill was in the political wilderness, but speaking out against appeasement. “An appeaser is one who feeds a crocodile, hoping it will eat him last,” he warned.

With the signing of the Munich Agreement (the 1938 pact among the major powers of Europe—except the Soviet Union and Czechoslovakia—allowing Nazi Germany to annex the Sudeten region of Czechoslovakia and its three million ethnic Germans), Churchill added, “And do not suppose this is the end. This is only the beginning of the reckoning. This is only the first sip, the first foretaste of a bitter cup which will be proffered to us year by year unless by a supreme recovery of moral health and martial vigour, we arise again and take our stand for freedom.”

“If Hitler invaded

hell, I would make

at least a favourable

reference to the

devil in the House

of Commons.”

His prescience proved out. Hitler plunged Europe into war, the appeasers were discredited, and, as prime minister, Churchill made his implacable hatred for the dictator clear. “If Hitler invaded hell, I would make at least a favourable reference to the devil in the House of Commons,” he said.

During the Battle of Britain, Churchill personally embodied the nation’s stalwart spirit of resistance as he strode down bomb-damaged streets—portly but pugnacious, Cuban cigar ever present, flashing a V sign to the cameras, unflappable and seemingly undefeatable.

“Hitler knows that he will have to break us in this island or lose the war,” Churchill said at the end of his “This was their finest hour” speech.

Britain held. Hitler’s attention and his massive military machine turned east toward the Soviet Union. Yet Churchill knew the struggle in the west would continue to be a grim one with the outcome uncertain. Even as he declared the intention of Britain and its Commonwealth allies to “never surrender,” Churchill knew victory could only be assured by having the United States onside as a co-belligerent.

“I shall drag the United States in,” Churchill had told his son, Randolph, within days of becoming prime minister. Although President Franklin Roosevelt was supportive, American public opinion was such that Churchill’s efforts yielded only a modest stream of weapons. That all changed on December 7, 1941, with Japan’s air attack on Pearl Harbor.

With America at his side, Germany suffering heavy casualties in the Soviet Union, and Britain maintaining a perilous grip in North Africa, Churchill knew time was now on his side rather than Hitler’s. The long march that would end in Berlin and see Hitler dead was beginning.

I wanted a close relationship with three countries—Britain, Italy, and Japan—but that gabbler and drunkard, Churchill, that hypocritical parasite…only wanted war,” Adolph Hitler lamented in May 1942. Throughout the mid- to late-1930s, his ambition to build formal alliances with these countries seemed feasible, especially after Germany and Japan signed the Anti-Comintern Pact (an anti-communist accord) in 1936 and Italy joined it in 1937.

This pact, among mainly fascist governments, greatly extended Germany’s international influence, but an alliance with Britain would assure Germany’s dominance over mainland Europe, give it valuable economic and political influence throughout the Commonwealth nations, and perhaps enable Germany to dedicate its entire military might to crushing the Soviet Union.

“That gabbler and drunkard,

Churchill, that hypocritical

parasite…only

wanted war.”

Under Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, Britain had become the undeniable chief proponent of appeasement—a policy that allowed Germany to extend its borders and assert ever more power within Europe. Even with the invasion of Poland and the Chamberlain government’s September 3, 1939, responsive declaration of war on Germany, Hitler continued to expect that Britain would ultimately cease hostilities and sue for peace on his terms.

Yet, even in the heady pre-war days of appeasement, Hitler was aware that Churchill lurked in the background and was an unwavering opponent. Although out of government, Churchill remained a powerful political voice, speaking eloquently and forcefully against the 1938 Munich Agreement.

When the German army launched its offensive against Poland, the fallacy of appeasement became clear. And when the blitzkrieg fell on Western Europe on May 10, 1940, Chamberlain resigned. Three days later, Hitler’s nemesis took the reins of power. “I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears and sweat,” Churchill warned his people.

In July, Hitler lashed out with the Luftwaffe in an attempt to gain air superiority over southern Britain and the English Channel. Destroying the British air force and aircraft industry would pave the way for an amphibious invasion. Hitler and his ministers expected a quick victory, but as summer turned to fall they were shaken by British steadfastness under Churchill’s stoic leadership.

Churchill’s resolve never wavered. His stubbornness baffled Hitler, leading him to declare Churchill’s “abnormal state of mind” could only be “explained as symptomatic either of a paralytic disease or of a drunkard’s ravings.” No amount of belittling Churchill, however, could offset Germany’s deteriorating situation under a leader either teetering on the brink of insanity or having fallen well over the edge.

Advertisement