Getting at an entrenched enemy is a problem as old as warfare, and one that grew more complex as the great and powerful retreated behind thicker and higher walls.

There were several ways of taking a castle or fort: scale the walls, bring them down by hurling large rocks at them, tunnel underneath, batter down the door, or starve out the population. All were slow or ineffective and largely unsatisfactory to impatient conquerors.

Confederate Army cannons are lined up in Richmond, Virginia, in 1865, near the end of the U.S. Civil War. (right) A British Army cannonball from the War of 1812. [Library of Congress/LC-B811-2728]

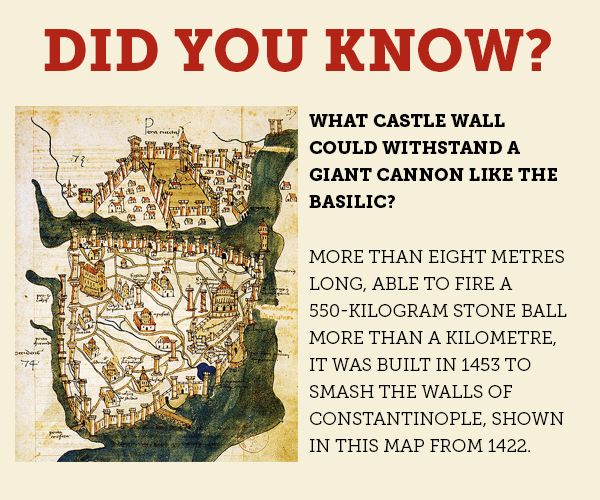

The cannon changed warfare and ended the era of castles.

The roots of the modern cannon can be traced back a millennium to China and an alchemist’s lucky mixture of saltpetre, sulphur and charcoal. Voilà, proto gunpowder, man-made thunder and lightning.

First prized for its noise and used in firecrackers to drive away demons, it didn’t take long to realize that gunpowder might also be used in a weapon. By 1225, the gunpowder recipe made its way West along trade routes, and within a century, European cannon designs made their way back East.

The cannon evolved from firelances—spears with attached tubes containing gunpowder and projectiles of some sort, to spit fire and mayhem when ignited. Cannons would allow the mayhem to be delivered from a distance.

The basic design emerged around 1300—projectiles and gunpowder were loaded into a large cylindrical container with a small hole bored in the solid end for a fuse. When lit, the fuse exploded the gunpowder, producing a rapidly expanding gas that propelled the projectiles farther than they could be thrown or flung. The design evolved from cylinders of bamboo, leather, wood and stone, to bronze, copper, iron and steel.

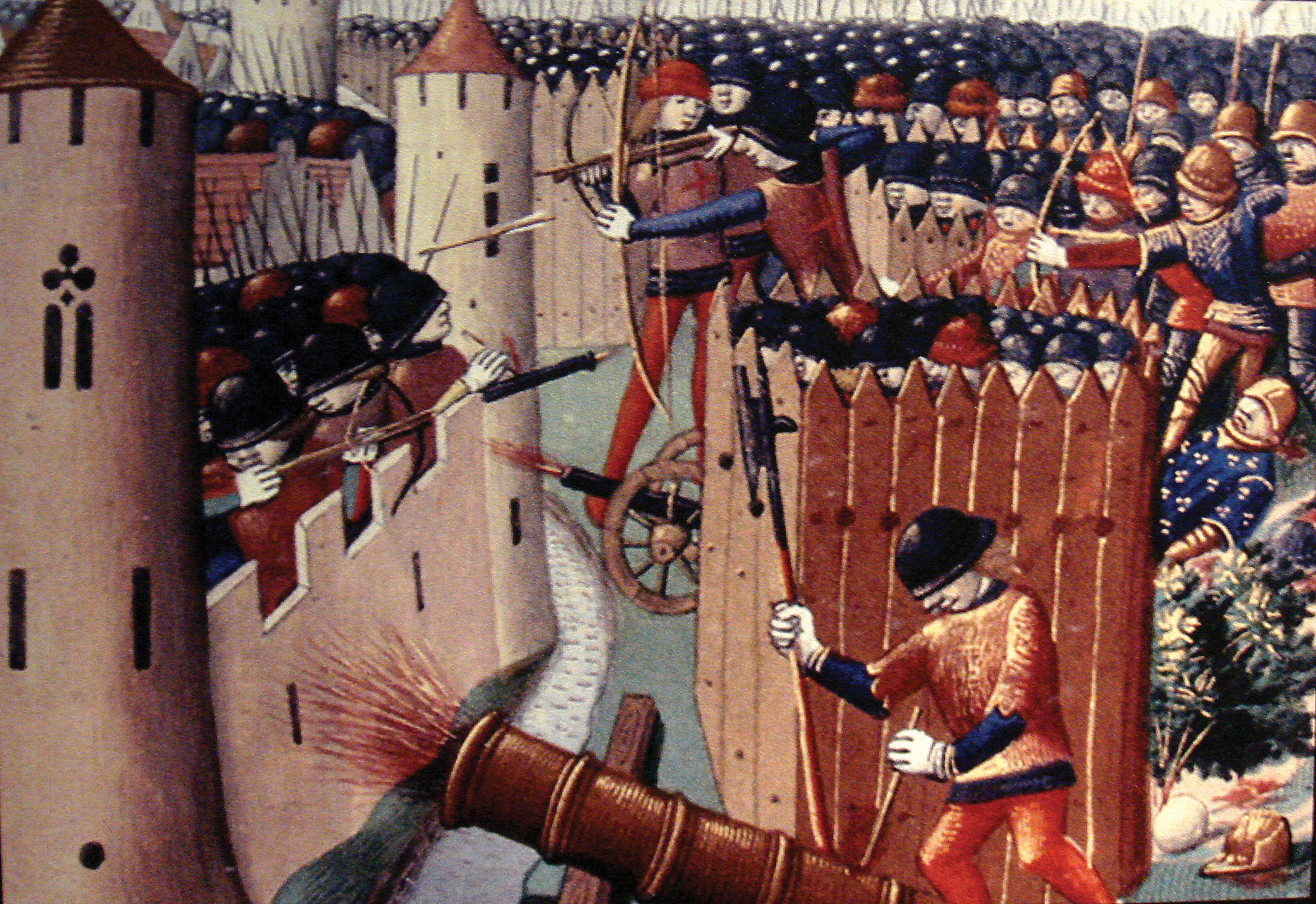

The French used the first metal cannon, the pot-de-fer, against the English during the Hundred Years War (1337-1453), which decided who got to sit on the French throne.

The technology kept improving through the ages. The body evolved from a vase shape into the tapered tubes of today. With the addition of gun carriages, horses could pull them to battle sites. Soon cannon were adapted for ships, then airplanes.

Projectiles became increasingly lethal—from arrows to stones to solid iron balls, some even chained together, the better to mow down enemy troops. Solid shot evolved into hollow shells, packed with explosives and shrapnel that exploded on impact or after they had reached their target.

Inevitably, the cannon evolved into purpose-built designs: field guns mounted on wheels for easy transport and mortars and howitzers to fire at a steep angle upwards, delivering balls, shells and bombs over defensive walls.

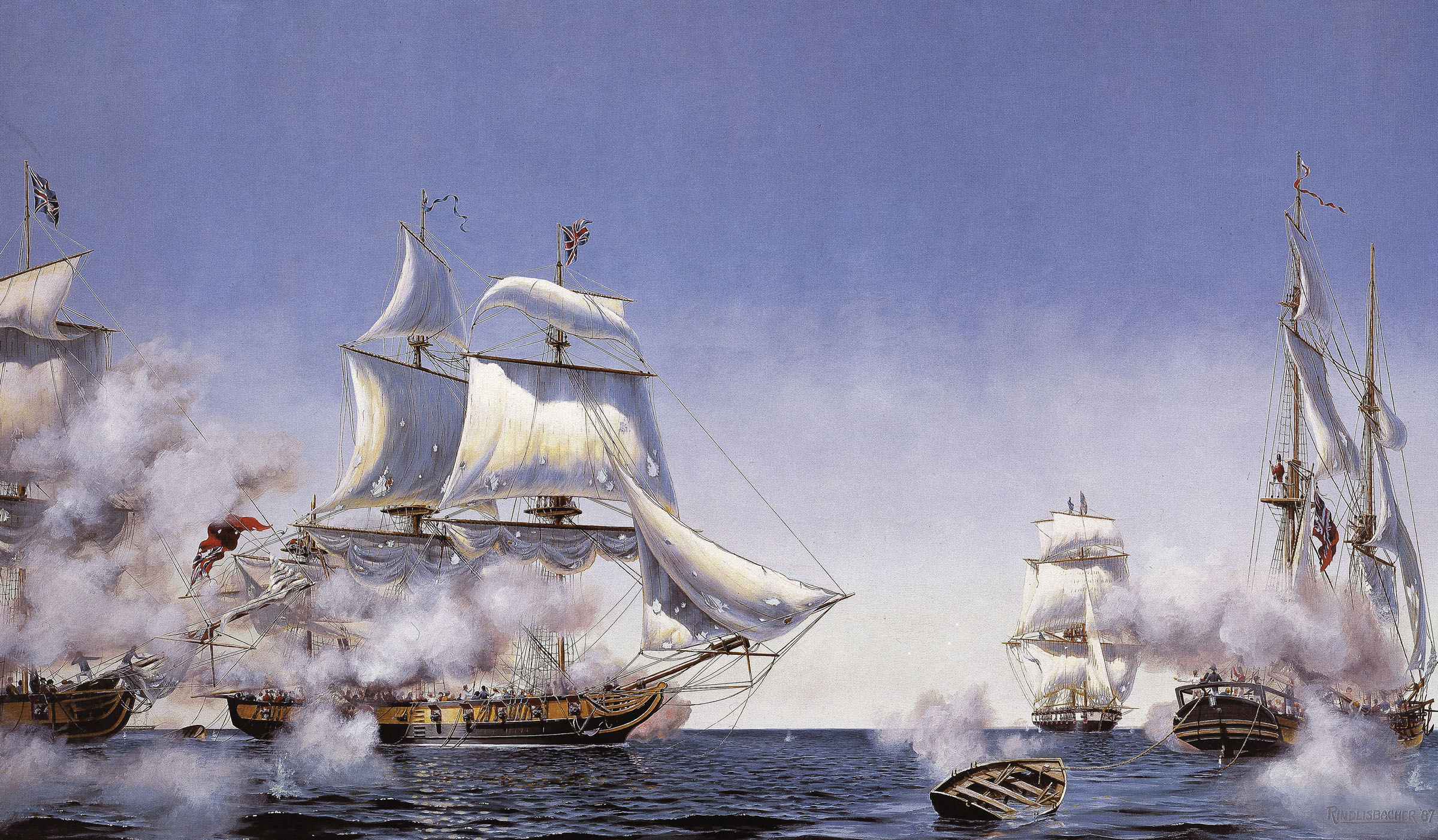

Armies now needed artillery, in addition to cavalry and infantry. So did navies. English ships in the 1600s had cannons that could penetrate a metre of solid oak and ranks of cannons to deliver broadsides to enemy vessels, batteries and towns.

The British and French brought their hostilities—and their cannons—with them to North America, where they played decisive parts in Canada’s history.

During the Battle of Quebec in October 1690 in response to a British demand to surrender, Louis de Buade de Frontenac, governor general of New France said, “My only reply to your general will be from the mouths of my cannon…!” His guns pulverized the British ships in the St. Lawrence and harried the militia on shore.

Cannon were used in the siege of Orleans in 1428-29 during the Hundred Years War and in exchanges of broadsides by the British and Americans in the Battle of Lake Erie in 1813. [Peter Rindlisbacher]

Five British field guns, abandoned during the hasty British retreat, were no doubt added to Quebec City’s defences. These sturdy, precious commodities frequently changed hands. The Molly Stark cannon, brought to New France in 1743, was captured by the British in 1759, the Americans in 1777 (whose general named it after his wife), the British in 1812 and the Americans in 1813. It was hidden away when the U.S. government melted down old guns for new weapons during the U.S. Civil War. The cannon is still fired during Independence Day celebrations.

In 1759, near the end of the Seven Years’ War, the British relentlessly bombarded French-held Fort Niagara with cannon and mortar fire from trenches. Dread can be read between the lines of a siege journal. On July 23, the British “unmasked another battery [of] cannon, three of which were 18-pounders.”

Outgunned, short of supplies and their relief column routed, the French surrendered July 26.

A few months later, after the Battle of the Plains of Abraham, British artillery commander Lt.-Col. George Williamson reported, “General Montcalm was kill’d by my grapeshot from a light six-pounder.”

Fifty years on, the six-pounder field gun was the most common artillery in the War of 1812. It could fire a round shot weighing nearly three kilograms more than a kilometre. Or a hollow shell packed with lead shot, invented in 1784 by Lieutenant (later Major-General) Henry Shrapnel, which would burst overhead of enemy troops, raining destruction. Shells from HMS Meteor provided some of the “bombs bursting in air” of the American anthem, “The Star Spangled Banner,” penned after the unsuccessful British attack on Fort McHenry.

Canadian gunners stay at their post despite ear-shattering gunfire during the attack on Thiepval in 1916, depicted here by Kenneth Forbes. [CWM/19710261-0142]

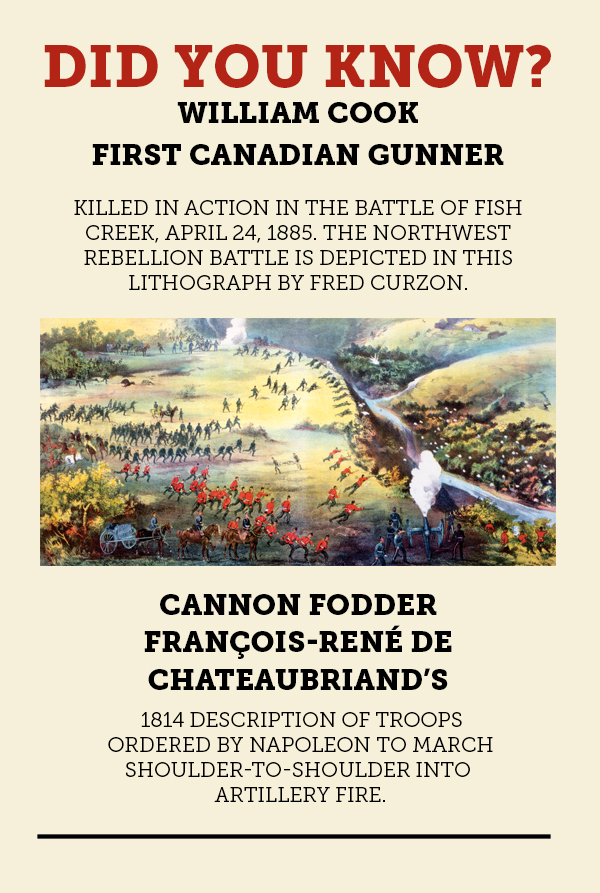

During the 1837 Rebellion, cannon fire dispelled the malcontents holed up in Toronto’s Montgomery’s Tavern. And the Royal Canadian Horse Artillery used field guns in action at the Battle of Fish Creek during the Northwest Rebellion in 1885, the first artillery unit to fire at the enemy since Confederation.

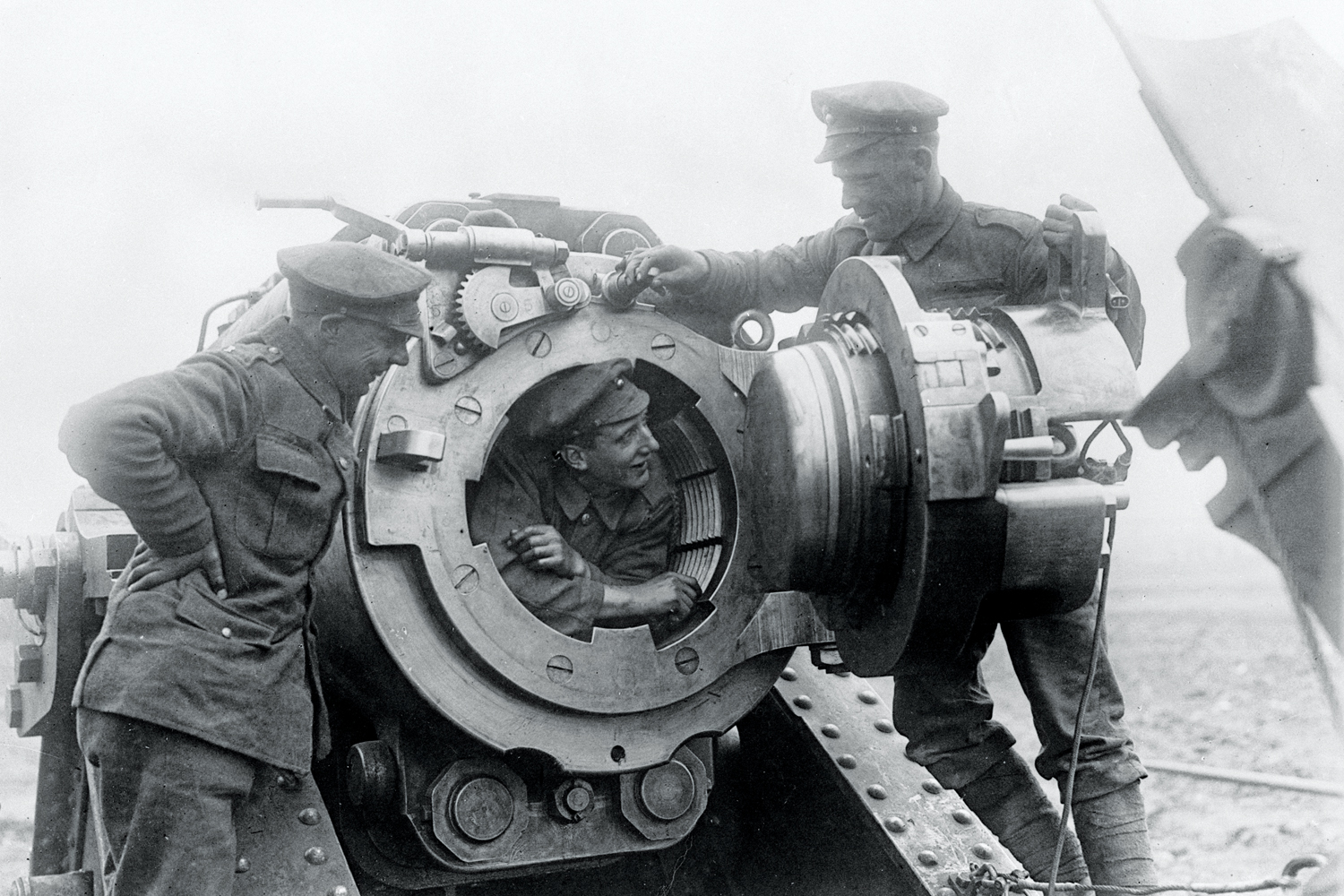

Canadian soldiers train in 1915 on a British QF 4.7-inch field gun, an adapted quick firing gun used by the navy. [DND/LAC 3405481]

But the First World War dwarfed everything before or since. It’s estimated that 1.5 billion shells were fired, about a third of which did not explode as intended.

Commonwealth armies had more than 10,000 18-pound field guns alone, and fired about 100 million shells of high explosives, shrapnel, incendiaries or gas. That’s an average of 43 rounds per minute for every minute of the war. Gunners became very adept at dropping shells exactly where needed—allowing development of the creeping barrages, which cleared the field for the Canadian infantry in the Hundred Days Offensive at the end of the war.

Gunners from the 5 RALC (5e Régiment d’artillerie légère du Canada) reload their 155-millimetre M777 cannon in Kandahar province, Afghanistan in 2007. [Combat Camera]

Second World War developments included sabot rounds, which block gas from escaping, increasing the muzzle velocity, and proximity fuses, which detonate automatically a preset distance from the target.

Big guns, big shells The BL 15-inch howitzer could fire 658-kilogram shells nearly 10 kilometres, with a muzzle velocity of 340 metres/second. At 85 tonnes, it was difficult to move in the trench warfare of the First World War. [AR2007-Z052-10]

Modern developments include the autocannon, capable of automatically firing a few thousand rounds a minute, and superguns, with a range of a thousand kilometres. Though it was briefly thought missiles would make cannons redundant, the age-old cannon designs are still recognizable among modern Canadian Armed Forces artillery.

Made in Canada: Canadian factories like this in Sorel, Que., produced 43,000 heavy guns, two million tonnes of explosives and 50,000 tanks and armoured gun carriers for the Second World War. [LAC/PA-174507]

Advertisement