At sundown on Nov. 11, communities across Canada marked the Armistice centenary with 100 tolls

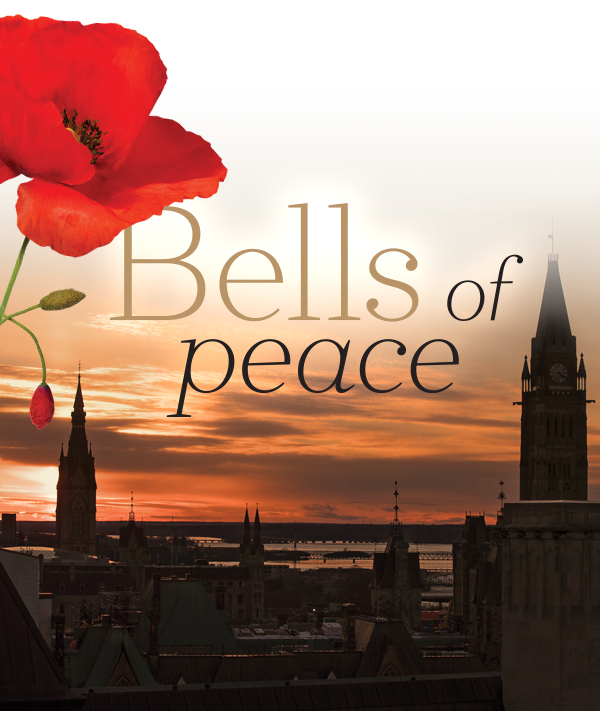

The Peace Tower in Ottawa, photographed on Nov. 11, 2018, as its bourdon (largest bell) was about to toll 100 times at sundown. [Stephen J. Thorne/Legion Magazine]

They came from small towns and big cities, villages and farms, east and west, north and south—619,636 volunteers and conscripts, two-thirds of whom served overseas during the First World War.

More than 66,000 were killed and 172,000 wounded in places like Ypres, the Somme, Passchendaele, Vimy Ridge. The place names are part of the lexicon of Canadian history, but they also died in faraway Egypt, Palestine, Gallipoli and on the Dvina River in northern Russia. At home, it was a sombre time as sons and brothers and fathers—daughters, sisters and mothers, too—enlisted and served overseas, so many never to return.

Across Great Britain from 1914 to 1918, regulations introduced under the Defence of the Realm Act limited the amount of bell-ringing that could take place. Thus, church bells were rarely heard. When the shooting stopped at 11 a.m., Nov. 11, 1918, and news of the Armistice broke, bells across Britain, Canada and the world spontaneously began to ring.

And not particularly well in some places: 1,400 bell-ringers from Britain alone were killed in the war and with so many at the front, accounts from the time recall how older ringers, former ringers and virtually anyone who could lend a hand joined in.

One hundred years after the end of the war to end all wars, bells in those little villages, small towns and big cities rang out once again, this time at sunset on Nov. 11, in keeping with the words of Robert Laurence Binyon in his 1914 poem “For the Fallen”:

They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old:

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning

We will remember them.

Dominion Carillonneur Andrea McCrady (right) at the keyboard in the bell tower of the Parliament Buildings in Ottawa. On Nov. 11, she played 18 pieces inspired by the 100th anniversary of the Armistice, concluding with “Last Post” at sundown before the Peace Tower’s bourdon was struck 100 times. [Stephen J. Thorne/Legion Magazine]

To see more photographs from the Bells of Peace event,

go to www.legion.ca/bellsofpeace

Advertisement