Graf Spee’s eagle, its swastika covered in many photographs, has been at the centre of controversy in Uruguay and elsewhere. [Wikimedia]

Treasure-hunters recovered the 350-kilogram bronze eagle from the wreck of the German battleship Admiral Graf Spee in 2006, but it was not until last year that a court ruled it belonged to the country in whose waters it was found: Uruguay.

That left authorities with a conundrum—what to do with a two-metre-tall bronze eagle sporting a wingspan of 2.8 metres and clutching a large swastika. It had lain at the bottom of the River Plate since December 1939, when Kapitän zur See Hans Langsdorff scuttled his damaged ship to prevent it from falling into Allied hands.

On June 16, 2023, Uruguayan President Luis Lacalle Pou announced a plan to melt the bronze and turn it into a sculpture of a dove. A Uruguayan sculptor, Pablo Atchugarry, was even commissioned to do the job of, as he described it, “transforming hate, war and destruction into a symbol of peace.”

Just two days later, the president scuttled the idea.

“In the few hours that have passed, an overwhelming majority of people has come forward who don’t share the decision,” said Lacalle Pou. “When you aim for peace, the first thing you need to do is create unity and this clearly didn’t.”

While Nazi artifacts have been displayed in museums worldwide virtually since the war ended in 1945, the fate of the Graf Spee eagle has attracted considerable attention at a time when neo-Naziism, extreme-right movements and anti-Semitism have gained traction in the U.S., Europe, South America and elsewhere.

Germany complained when the relic was exhibited briefly several years ago, and asked the Uruguayan state not to showcase what it described as “Nazi paraphernalia.”

When a Uruguayan court ruled that the eagle should be auctioned off to pay the private investors who had financed its recovery, the Simon Wiesenthal Center, a Jewish human rights organization dedicated to Holocaust research and remembrance, warned it could fall into the hands of Nazi sympathizers.

The government in Montevideo appeared unprepared when Uruguay’s supreme court ruled last year that the eagle belonged to the state.

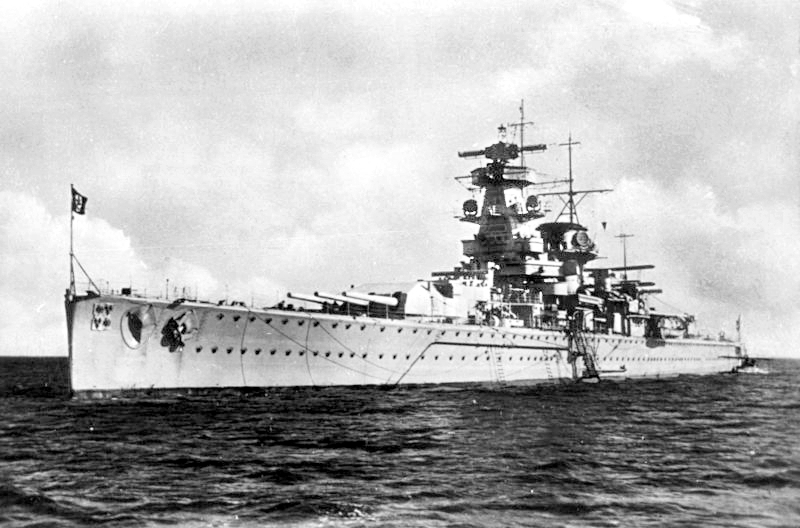

Like its sister ship, Admiral Sheer, Admiral Graf Spee was a Deutschland-class Panzerschiff (armoured ship) in Hitler’s Kriegsmarine. [Bundesarchiv/Wikimedia]

The treaty that formally ended the First World War imposed varying restrictions on militarization of the main combatants, especially the aggressor, Germany. These and other punitive measures helped fuel the rise of Adolf Hitler and his Nazi Party, who capitalized on the hardships and dissatisfaction of the German people.

Admiral Graf Spee and its sister ships were designed to outgun any cruiser fast enough to catch them. That in itself was a challenge: only a few battle cruisers in the Anglo-French navies had the speed and armament to sink the vessels the British dubbed “pocket battleships,” with their top speed of 28 knots (52 km/h).

Named for Admiral Maximilian von Spee, commander of the Kaiser’s East Asia Squadron who was killed in action off the Falkland Islands in 1914, Langsdorff’s ship conducted five non-intervention patrols during the Spanish Civil War in 1936–1938 and participated in the coronation review of King George VI in May 1937.

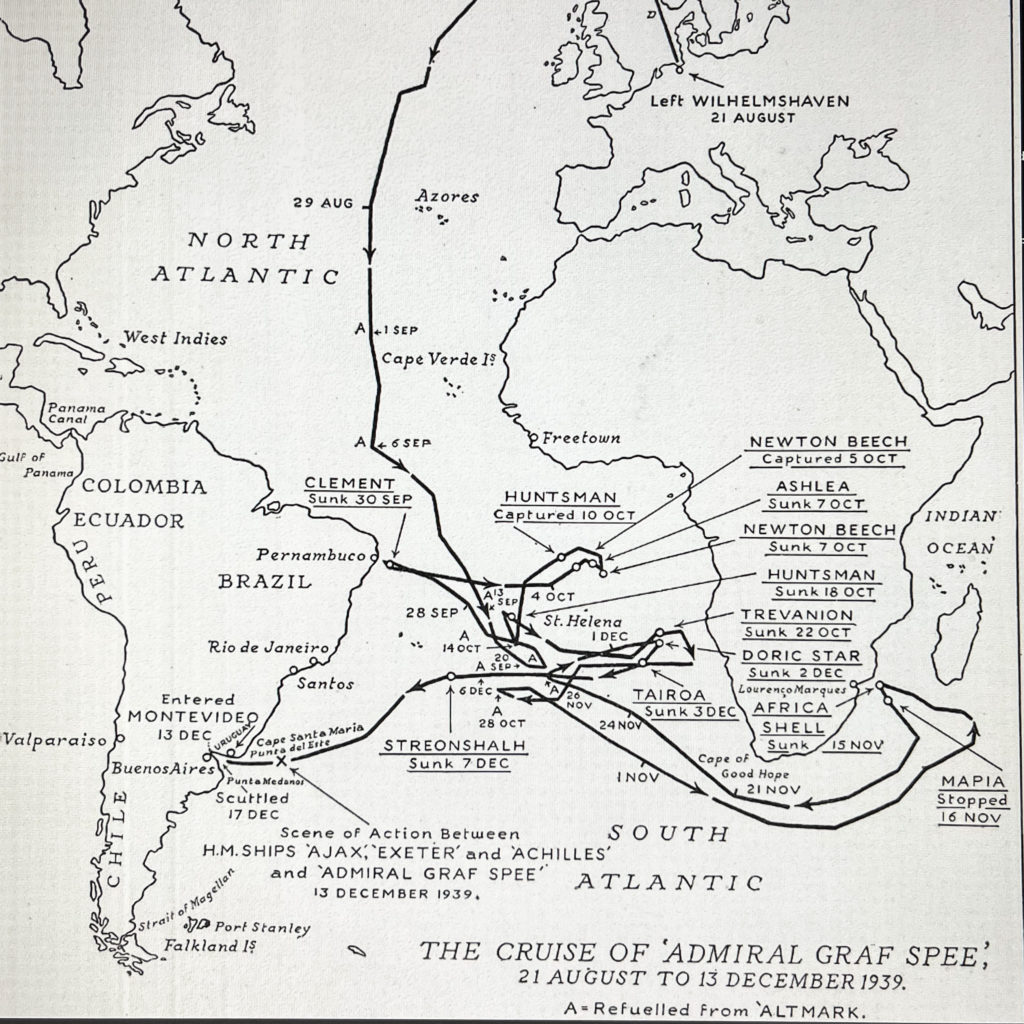

Less than two years later, before the outbreak of the Second World War, Graf Spee was deployed to the merchant sea lanes of the South Atlantic. Between the outbreak of the war in September and December 1939, it sank nine merchant ships in the Indian and South Atlantic oceans, totalling 50,089 gross register tons.

No lives were lost, however, as Langsdorff was working under prize rules requiring him to stop ships, search them for contraband, and safely evacuate their crews before sinking them. He had been ordered to avoid any combat.

His ship’s reputation was such that the Royal Navy assembled nine Anglo-French groups to search for it, including four aircraft carriers, three battle cruisers and 16 cruisers.

Treasure hunters recovered the eagle from the waters off Montevideo in 2006.

[Unknown]

Before Langsdorff and the 1,000 or so crew aboard Graf Spee sunk their sixth victim, the British cargo liner Doric Star, near southwest Africa on Dec. 2, 1939, the merchant captain ordered the signal R-R-R (I am being attacked by a raider).

Harwood suspected the raider would strike next at merchant shipping off the River Plate estuary between Uruguay and Argentina. He ordered his squadron to steam toward the area’s richest hunting ground—the most congested part of the South Atlantic shipping routes.

Soon after, a Norwegian freighter saw Graf Spee’s searchlights and radioed it was headed toward South America. Three cruisers of Force G rendezvoused off the estuary on Dec. 12. The fourth cruiser, Cumberland, was in refit in the Falklands and took to sea to patrol off the islands.

Graf Spee sunk three more merchants on its transatlantic trek. But its reconnaissance aircraft broke down, so it was sailing essentially blind as it neared the South American coast.

At 5:30 a.m. on Dec. 13, German lookouts spotted a pair of masts off their ship’s starboard bow. Langsdorff assumed this to be the escort for a convoy mentioned in documents recovered from one of his recent victims. At 5:52, however, his crew identified the ship as Exeter.

It was accompanied by a pair of smaller cruisers, but Langsdroff would only realize that later. The German skipper ordered his ship to battle stations and closed at maximum speed. Even with the two additional light cruisers, his “pocket battleship” outgunned the British.

What he couldn’t know was that, during his time at the Royal Naval War College between 1934 and 1936, his opposing commander, Harwood, had devised the British combat instructions for engaging a pocket battleship with a cruiser squadron.

The strategy specified an immediate attack, day or night. In a daytime action, ships would attack as two units, thus Exeter would go in separate from Ajax and Achilles.

British naval accounts of the battle explain that, by attacking from two sides, Harwood hoped to give his lighter warships a chance of overcoming the German advantages of greater range and heavier broadside by dividing the enemy’s fire.

At 6:08 a.m., the British spotted Graf Spee.

Graf Spee’s path to destiny, from Wilhelmshaven to South Africa to Uruguay. [S.D. Waters/Achilles at the River Plate]

For victory, the British had only to damage the raider enough so that it was either unable to make the transatlantic journey or handicapped as it entered a subsequent battle with the British Home Fleet.

Even losing all three cruisers at the River Plate would not severely alter Britain’s prodigious naval capabilities. Graf Spee, on the other hand, was one of the Kriegsmarine’s few capital ships. The British could, therefore, afford to risk a tactical defeat if it brought strategic victory, Eric Rust wrote in Command Decisions: Langsdorff and the Battle of the River Plate.

As Exeter turned northwest, and Ajax and Achilles turned northeast, Graf Spee opened fire on Exeter at 17,000 metres. It was 6:18 a.m. Exeter opened fire two minutes later; Achilles a minute after that; Exeter fired its aft guns at 6:22; Ajax opened up a minute later.

“As I was crossing the compass platform, the captain hailed me,” Lieutenant-Commander Richard Jennings, Exeter’s gunnery officer, told Max Arthur for the book Lost Voices of the Royal Navy, “not with the usual rigmarole of ‘Enemy in sight, bearing, etc.,’ but with ‘There’s the fucking Sheer! Open fire at her!’

“Throughout the battle,” said Jennings, “the crew of the Exeter thought they were fighting the Scheer. But the name of the enemy ship was of course the Graf Spee.”

At 6:23, an 11.1-inch shell from Graf Spee burst just short of Exeter, abreast the ship. Shrapnel killed Exeter’s torpedo crews, damaged its communications, riddled the funnels and searchlights and wrecked the vessel’s Walrus aircraft just as it was about to be launched for gunnery spotting.

Three minutes later, Exeter took a direct hit on her ‘B’ turret. Shrapnel swept the bridge, killing or wounding all inside except the captain and two others. The ship had to be steered via messenger chain for the rest of the battle.

HMS Exeter (foreground) and HMS Achilles (behind) in action with Graf Spee (right rear).[Cdr (ret’d) Eric Erskine Campbell Tufnell RN/U.S. Naval Historical Center/Wikimedia]

At 6:38, as Exeter turned to fire its port torpedoes, it took two more direct hits—one putting ‘A’ turret out of action, the other penetrating the hull. The British ship was burning, severely damaged, flooding, and listing seven degrees. Exeter had only ‘Y’ turret still in action, and that was being directed by a naked eyeball.

Yet it was Exeter that dealt the decisive blow: one of the British ship’s 8-inch shells penetrated two decks before it exploded in Graf Spee’s funnel area, destroying the German’s raw fuel processing system and leaving it with just 16 hours’ sailing capacity.

The battle was an hour old. The big ship didn’t have the fuel to make it home. Graf Spee was doomed.

The only refuge the unseaworthy German could take was in the officially neutral port of Montevideo. Langsdorff hauled his ship round from an easterly course toward the northwest and laid smoke. Ajax and Achilles were now behind him.

Exeter attempted to pursue its foe, but was soon forced to break off from a running battle. Ajax and Achilles took up the pursuit, one on either side of their prey.

Achilles overestimated Graf Spee’s speed and by 10:05 a.m. was within range of the German guns. Graf Spee turned and fired a pair of three-gun salvoes with its fore guns. Achilles turned away under a smokescreen.

By early evening, it was evident the German was making for the River Plate estuary. Harwood ordered Achilles to shadow Graf Spee while Ajax would watch the channels in case Langsdorff tried an escape.

Thirty-six of the German crew were dead; 60 wounded. The British had lost 72 killed; 28 wounded. No ship escaped unscathed, and the heavies got the worst of it.

Graf Spee entered Montevideo and dropped anchor around 10 after midnight on Dec. 14. Though Uruguay was technically neutral, it had received significant British aid—the main hospital where most of the wounded were taken was British—and the government favoured the Allies.

Graf Spee is scuttled in Montevideo, Uruguay harbour following the Battle of the River Plate in December 1939.

[York Space Institutional Repository/Wikimedia]

Article 14 states a “belligerent war-ship may not prolong its stay in a neutral port beyond the permissible time except on account of damage.”

British diplomats pressed for the German’s prompt departure. The Germans released 61 captured British merchant seamen. Langsdorff asked the Uruguayan government for two weeks to repair his vessel.

British diplomats continued to insincerely demand for the ship to leave port, all the while manipulating circumstances so that the German would remain until a healthy British force could reach the area. Meanwhile, they falsely leaked to the enemy that one was already there.

In fact, the only robust and fully armed Allied ship anywhere close was Cumberland, which arrived from the Falklands in short order.

Down to 20 minutes of ammunition, Langsdorff was convinced he would face a far superior force upon his departure from the River Plate. Meanwhile, British diplomatic staff watched and waited, ensuring the ship didn’t try an escape.

Langsdorff consulted with the Kriegsmarine brass back in Germany and received orders that allowed some options, but not internment in Uruguay, where the Germans feared authorities could be persuaded to join the Allied cause.

Ultimately, the skipper chose to scuttle his ship in the River Plate estuary on Dec. 17, avoiding unnecessary deaths for no particular military advantage. Hitler was enraged.

The crew of Admiral Graf Spee were taken to Buenos Aires, where Langsdorff shot himself on Dec. 19—probably a more merciful death than Hitler would have afforded him. He was buried in the Argentine capital with full military honours. Several British officers attended.

Many of his surviving crew took up residence in Montevideo, helped by locals of German origin. Dead Germans were buried in the Cementerio del Norte, Montevideo, Uruguay.

Advertisement