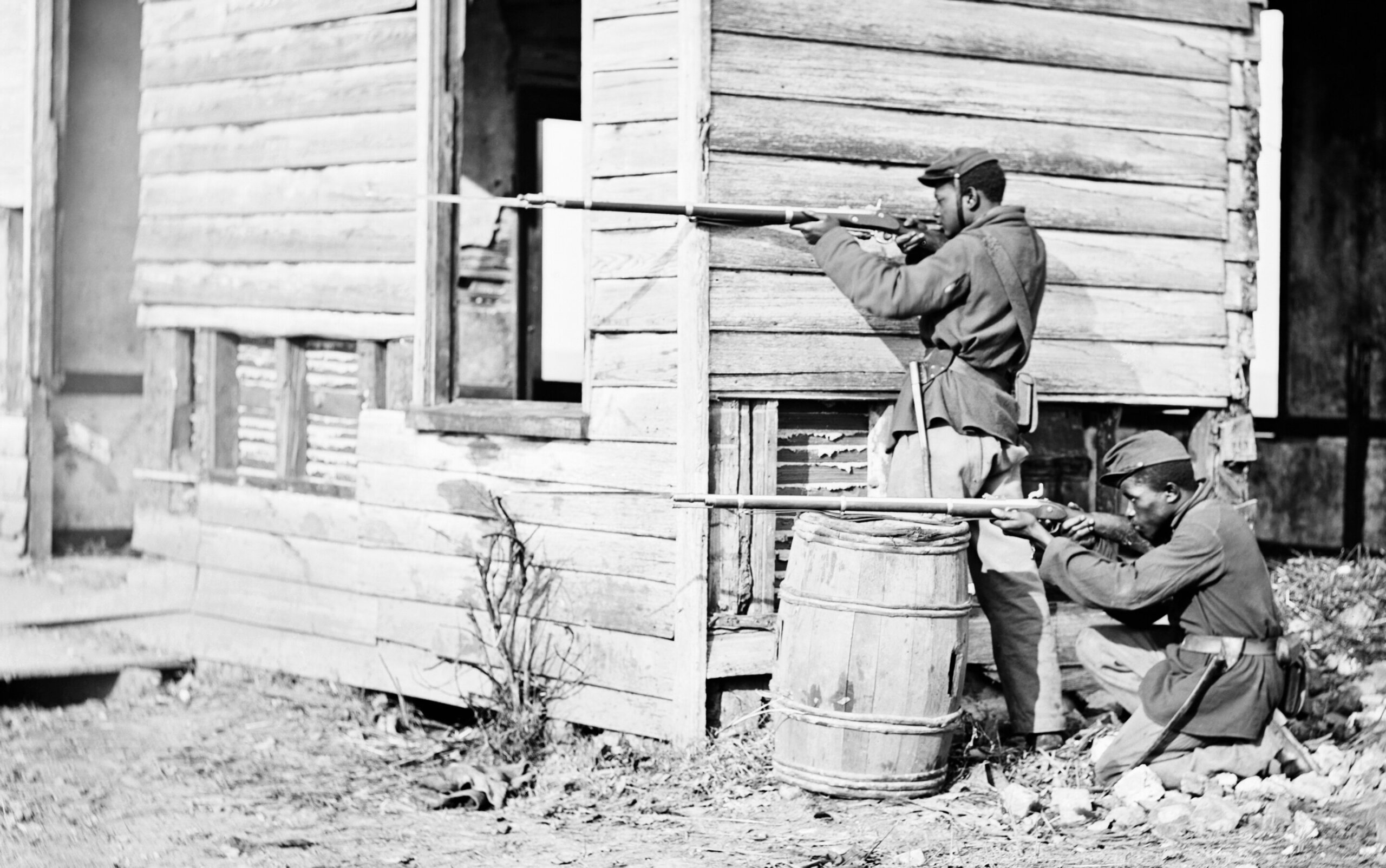

African-American Union soldiers are shown at Dutch Gap, Virginia, in November 1864 wearing typical Union uniforms and wielding the 1853 Enfield rifles used by U.S. Colored Troops.

[U.S. Library of Congress]

Louisville was a Union stronghold and operations base for the war’s western theatre—the centre of planning, supply, recruiting and transportation for numerous campaigns throughout the four-year struggle between the states. The beef was destined to help feed the city and its 100,000 blue-coated troops.

The men, most of whom had escaped slavery to enlist, spread out over a large area, driving the animals across the cold, snow-covered Kentucky countryside. Then, on Jan. 25, those at the rear of the herd—known in cowboy parlance as drag riders, or “drags”—were attacked by Confederate guerrillas just outside Simpsonville.

Kentucky was officially neutral, controlled by the Union army. But unattached guerillas operated throughout what was essentially a divided state, conducting raids of opportunity, generally on softer or more vulnerable Union targets.

Known as bushwhackers, they were generally made up of men who wanted to fight free of military restrictions by surprising, ambushing and killing Union troops rather than following what at the time were considered the rules of war.

‘E’ Company’s drag riders were separated from half their number by the huge herd when they were set upon by the 15 guerillas wielding six-shot navy revolvers.

“What followed wasn’t a battle—it was a slaughter,” Philip Mink, a University of Kentucky archeologist, told a recent conference of the Society for American Archaeology in Denver. “Most of the [dead] were shot in the back while fleeing, despite wearing the uniform of the U.S. Army.

“Guerrillas definitely targeted them because they were Black.”

Many of the Union men were carrying 1853 Enfield rifles, muzzle loaders that are virtually impossible to reload on horseback. Others were hampered by powder dampened by foul winter weather. The Shelby Record reported in a 1913 account of the attack that the Union men fired only a single shot before they scattered.

“It is presumed that the negroes surrendered and were shot down in cold blood,” the Louisville Journal reported the day after the attack. “It was a horrible butchery, yet the scoundrels engaged in the bloody work shot down their victims with feelings of delight.”

The 1853 Enfield Rifle-Musket was the second-most used infantry weapon in the U.S. Civil War. It was 1,400mm long and fired a .577-calibre Minié-type lead ball projectile, propelled by black powder and a copper percussion cap. Because it was a muzzle-loading weapon, it was unsuited for cavalry use.

[Wikimedia]

“The ground was stained with blood and the dead bodies of negro soldiers were stretched out along the road,” the Journal reported. “It was evident that the guerrillas had dashed upon the party guarding the rear of the cattle and taken them completely by surprise.

“They could not have offered any serious resistance, as none of the outlaws were even wounded.”

The cattle had stampeded and, unable to safely or quickly work their way back to the scene, the 40 or so men up front had scampered for safety.

“After the wholesale murder, [the guerillas] took good care to secure the arms and ammunition of the slain,” the paper reported, admonishing three of the Black unit’s officers for “loafing in the tavern” at the time of the attack. The company captain was actually in a Simpsonville shop warming his frozen feet and buying boots when someone ran into the store and shouted: “Here comes Coalter and his guerrillas!”

The officer reportedly hid.

A subsequent investigation confirmed that many of the ‘E’ Company men had, indeed, tried to surrender, only to be shot in cold blood. One survived by feigning death, another “by secreting himself behind a wagon,” yet another by running until he was met “several miles from the scene of tragedy, wounded and nearly exhausted.”

The main guerillas were identified as well-known “scoundrels,” including Dick Taylor, William Clarke Quantrill, (One Arm) Samuel Berry, David (Black Dave) Martin and Captain Isaiah (Big Zay) Coalter.

Simpsonville was far from the first racially motivated massacre of the bitter war, which claimed the lives of nearly 40,000 Black soldiers, 30,000 of them by infection or disease.“Inevitably, the issue of Confederate war crimes hinges on the status of blacks, which poisoned the entire military effort of the South,” The National Post reported in a 2015 feature.

White officers had begun collecting escaped slaves for service in the Union army in the latter half of 1862. By August 1862, the Confederate army’s high command had ordered the execution of any white officer caught leading Black soldiers.

In November, a Confederate raid against a Union-held island off South Carolina yielded four Black prisoners, who were executed with the approval of Confederate President Jefferson Davis.

Small-scale atrocities persisted sporadically into 1863, the Post reported, “but the gloves really came off in 1864, when outrages seemed to occur almost every month.”

In February 1864 at Olustee, Florida, Confederate troops slaughtered about 50 Black troops caught up in a Union defeat. A Southern officer, William Penniman, recalled being puzzled by the persistence of gunfire long after the fighting. He asked another officer what was happening and was told: “Shooting niggers, sir. I have tried to make the boys desist, but I can’t control them.”

When an outnumbered “colored” unit of the Union Army surrendered Fort Pillow, Tennessee, on April 12, 1864, the rules of war required the Confederates to take the 262 Black soldiers prisoner. Instead, they massacred them, along with neighboring Black civilians.

A historical marker and military-style headstones honour the victims of the Simpsonville Massacre.

[Brian Mabelitini/Kentucky Office of State Archaeology]

And on July 30, 1864, at Petersburg, Virginia, up to 100 Black soldiers who fell into Confederate hands were murdered.

Throughout the war, both sides were eager to exchange prisoners, but the Confederacy refused to exchange former slaves.

Wartime lynchings and other atrocities against uniformed and non-uniformed Blacks were common in Kentucky, and the greater South, and continued as they had before on into the Jim Crow era.

Not all Black PoWs were murdered out of hand, however.

In Mobile, Alabama, Confederate units were using 575 Black prisoners as involuntary labour in late 1864. Other prisoners were forced to build fortifications under fire at Richmond, Virginia, and Charleston, South Carolina.

Union forces were so appalled by this tactic that they ordered Confederate prisoners to do the same for them. The South subsequently ceased the practice.

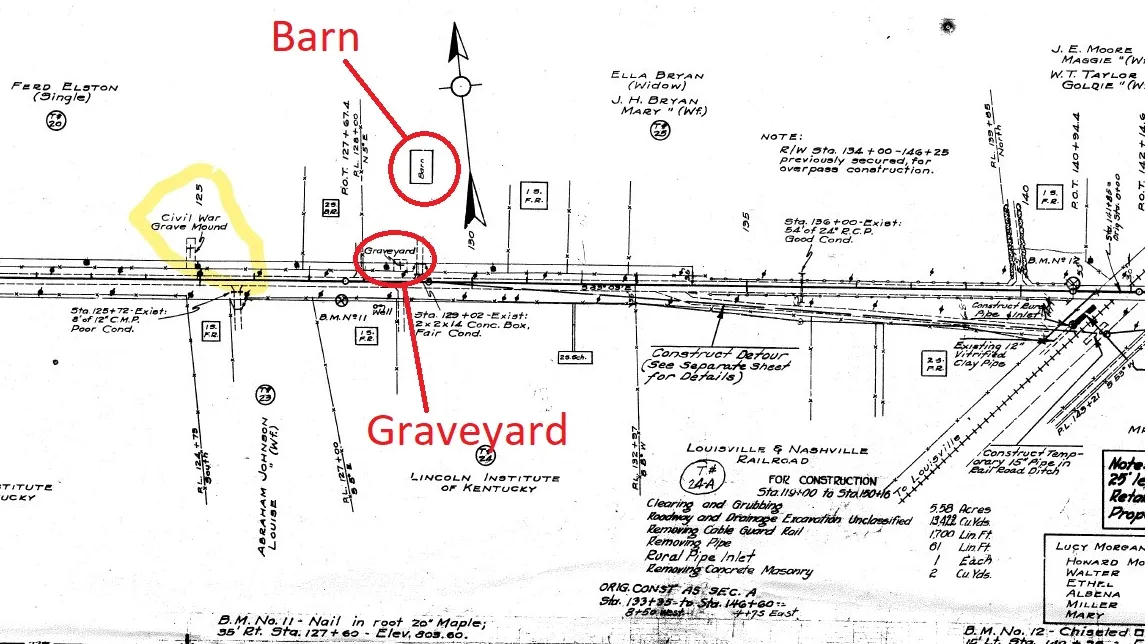

The Simpsonville dead were buried in a mass grave—a trench, said one report of the day. No formal record of the burial site was made, and the Union burial commission did not attempt to locate the soldiers’ remains after the war. Their precise location became lost to time.Until, that is, a recent geophysical survey apparently located the soldiers’ final resting place on what is now a soybean farm. Unexpectedly, the study revealed not one but two suspected mass graves.

The researchers believe that one site holds those killed during the ambush, while the other, is thought to hold the remains of those who died from their wounds after the battle. Excavations were planned for later in 2025, following the soybean harvest.

“The massacre was largely forgotten in historical accounts until 2008, when the Kentucky African American Heritage Commission awarded a Lincoln Preservation Grant to the Shelby County Historical Society to investigate the Simpsonville Slaughter,” reports The Kentucky African American Encyclopedia.

“Locals assumed that the victims of the attack had been buried in a mass grave in a nearby African American cemetery that had been abandoned for 40 years.”

Archeologist Brian Mabelitini collects ground-penetrating radar data over the area marked as a Civil War burial mound on the 1936 map. [Brian Mabelitini/Kentucky Office of State Archaeology]

Still, the Simpsonville Massacre isn’t in most history books because, the 1989 film “Glory” notwithstanding, “until fairly recently the efforts—even the existence—of African American troops have been largely ignored,” Murray State University historian Bill Mulligan told the Louisville Courier Journal in 2022.

“Armed Black men were a Southern white nightmare brought to life,” Mulligan said.

“When Black units did engage in combat with rebel forces, very few prisoners were taken. Simpsonville, Saltville and Fort Pillow are extensions of this killing. Black soldiers were part of the visceral fear of empowered Black men—they were to be slaughtered so as to erase their existence.”

—

The fates of the principal guerillas in the Simpsonville Massacre:

Dick Taylor purportedly led the Jan. 25, 1865, attack. He was killed in hand-to-hand combat with a Union soldier three days later after he and several others spent the night at his father’s house in Anderson County. His father, Grayson Taylor, reported the stay to Union authorities after the guerillas left. Taylor and another gang member were subsequently captured. Both died during a botched escape attempt.

William Clarke Quantrill was a former schoolteacher-turned-bandit roaming the Missouri and Kansas countryside hunting escaped slaves. His group evolved into Quantrill’s Raiders. He was mortally wounded in Central Kentucky in one of the last engagements of the Civil War. He died three weeks later, on June 6, 1865, age 27.

(One Arm) Samuel Berry surrendered to a detachment of mounted Union infantry on Dec. 8, 1865, and was convicted by a military court in Louisville of seven murders and the charge of being a guerilla. His death sentence was commuted to 10 years’ hard labour. He died in prison on July 4, 1873. He was 34.

David (Black Dave) Martin was a former Rebel soldier and escaped prisoner of war. He was arrested at his home in July 1865 and convicted by a military court of conducting guerilla warfare. He received two years’ hard labour but was released early as a Confederate veteran with dependents. He died in August 1896, age 68.

Isaiah (Big Zay) Coalter, all six-foot-six of him, made his name robbing, plundering and murdering in multiple Kentucky counties. He was mortally wounded in the chest by a gunshot from Ed Terrell, a Union home guard, three days after Simpsonville. He made it to an aunt’s house in Anderson County and died Feb. 6, 1865. He was 21.

—

Sue Mundy was named as a participant in the Louisville Journal stories of the day. In fact, ‘Sue Mundy’ was a creation of reporter George D. Prentice, who inserted the fictional woman into multiple accounts of real guerilla actions to cast the Union commander in Kentucky, Major-General Stephen G. Burbridge, as an incompetent. It is thought that Mundy was based on one of two actual guerillas, possibly both:

Henry C. Magruder was a Confederate soldier and escaped PoW who, after finding himself trapped behind enemy lines, rounded up other lost Rebels and started raiding, plundering, raping and killing. He is known to have participated in the Simpsonville Massacre and claimed to have been the original Sue Mundy in a posthumous memoir, Three Years in the Saddle: The Life and Confession of Henry Magruder, The Original Sue Munday, The Scourge of Kentucky. Wounded during capture, he was convicted of eight murders and conducting guerilla warfare. At age 22, he was nursed back to health in prison and hanged in October 1865.

Marcellus Jerome Clarke was a Confederate captain who was known to wear his hair long and had smooth-faced features. Some claimed he inspired Sue Mundy. Caught by Union troops in Meade County on March 12, 1865, he was tried, convicted and hanged within days. Prentice denied Clarke was Mundy.

Advertisement