The French town of Vire was bombed by Allied aircraft late on June 6, 1944; 95 per cent of the town was destroyed.

[ Conseil Régional de Basse-Normandie/U.S. National Archives]

“My dear Henri, it’s shameful to massacre the civilian population as the supposed Allies are doing,” she wrote her husband, who was being held in a German prison camp. “We are in danger everywhere.”

The French port on the Cotentin Peninsula was a key stepping-stone in the Allied advance—a coveted harbour, a heavily defended German garrison of 40,000 troops, and one of the Allies’ earliest objectives in the weeks after D-Day.

Allied aircraft dropped leaflets warning residents to “LEAVE IMMEDIATELY! YOU DON’T HAVE A MINUTE TO LOSE!” Ninety per cent of its residents left; 5,000 stayed put; besides those killed in the pre-invasion bombardments, 23 died during post-D-Day fighting when a bomb hit their shelter; 27 more were killed on a farm overlooking the city.

Children watch an American Jeep drive through the ruined centre of Saint-Lô in August 1944. More than 90 per cent of the town was destroyed by Allied bombings that summer.

[Conseil Régional de Basse-Normandie/U.S. National Archives]

Indeed, the liberation of Europe was decidedly not, for the liberated, all smiling faces, passionate kisses and floating rose petals.

For Normans, D-Day and its aftermath were “a bit of a confusion of feelings,” said University of Caen historian Françoise Passera. “We cried with joy because we were freed, but we also cried because the dead were all around us.”

Between 1940 and 1945, Allied air forces dropped nearly 550,000 tonnes of bombs on 1,570 French cities and towns. No fewer than 68,778 men, women and children were killed and 100,000 wounded. Some 432,000 houses were destroyed; another 890,000 were damaged.

But, for decades, “civilian victims were swept under the carpet somewhat to not offend the Americans,” Passera told The Associated Press. “And to not offend the British. This was not a subject that could be raised very easily by French authorities.”

[Various sources]

Within days of the June 6 landings by Canadian, American and British forces, a list of Norman cities, towns and villages were in ruins.

Some 20,000 French civilians were killed during the D-Day invasion (10,000 on June 6 alone) and the Normandy campaign that ended with the liberation of Paris in late-August 1944.

The destruction stretched along the Loire River (Nantes and Tours), on the Brittany coast (Brest, Lorient and Saint-Nazaire), the Atlantic coast (notably at Royan), and in the north of France (Lille, Amiens and Dunkirk).

Caen lost 1,741 residents. Rouen (883), Saint-Lô (400) and Falaise (350) were also hard-hit. Proportionally, the small town of Evrecy in the Calvados department suffered most: 62 dead in a population of 460.

In Saint-Lô, a northwestern French commune, Marguerite Lecarpentier’s 19-year-old brother, Henri, was killed helping another man pull a teenage girl out from under debris when the town was bombarded again. All three were killed. Marguerite was six at the time. Her father later identified her brother’s body by his new shoes. The family fled.

“It was terrible because there was rubble everywhere,” Lecarpentier recalled. Her mother waved a white handkerchief as they walked to identify themselves as civilians to the planes passing overhead.

A French woman and a British soldier walk among the devastation in liberated Caen on July 10, 1944.

[E.G. Malindine/Imperial War Museums]

“It was the price to pay,” she told The Associated Press. “It can’t have been easy.

“When one thinks that they landed on June 6 and that Saint-Lô was only liberated on July 18 and they lost enormous numbers of soldiers.”

Indeed, Allied casualties in the Normandy campaign numbered 73,000 troops killed and 153,000 wounded—5,000 Canadian dead and 18,700 total Canadian casualties among them.

After the campaign officially ended, Le Havre fell under 12,000 tonnes of Allied bombs between Sept. 5 and 11, 1944. More than 5,000 civilians were killed.

“The French supported precision attacks on legitimate targets but deplored apparently indiscriminate high-altitude bombing,” University of Reading’s Lindsey Dodd and Andrew Knapp wrote in their paper “‘How Many Frenchmen Did You Kill?’ British Bombing Policy Towards France, 1940–1945.”

“The association of the latter with the USAAF damaged the Americans’ standing with the French.”

Monte Cassino then and now.

[WW2 History Book]

“Everybody was a bit angry with the Americans because at the end of the day they were the ones killing civilians,” said a Frenchman named Henri, who was 19 when he witnessed his fiancée, uncle and cousin killed just metres away.

“Caen was bombed, for example—why? For nothing,” he told the RFI news service in 2019. “There were hardly any Germans there. All these towns were massacred.”

In the Italian town of Cassino, residents are still bitter over the bombing of their beloved 1,415-year-old Benedictine abbey on Monte Cassino, a promontory rising 520 metres above the community nestled in Italy’s Latin Valley southeast of Rome.

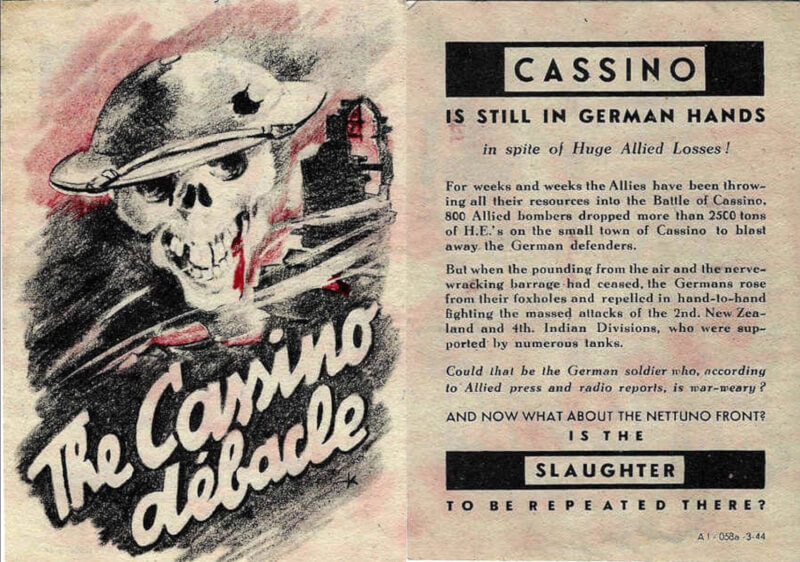

Nazi propaganda leaflets sought to capitalize on the abbey’s devastation. [ psywarrior.com]

The sprawling complex, founded by Saint Benedict around 529 AD, was subsequently destroyed in a massive bombing raid after an unnamed British junior officer evidently mistranslated a radio intercept, taking the German word for abbot for a similar word meaning battalion.

Published in 2000, Rupert Clarke’s autobiography, With Alex at War claimed that was all the subaltern’s superiors needed to believe the Werhmacht was using the monastery as its command post, breaching a Vatican agreement that declared it neutral.

It’s now widely believed the Germans were not using the abbey for observation. It was only after Allied generals ordered the bombing and the planes were in the air that a British intelligence officer, Colonel David Hunt, rechecked the full radio intercept and discovered it actually said: “The abbot is with the monks in the monastery.”

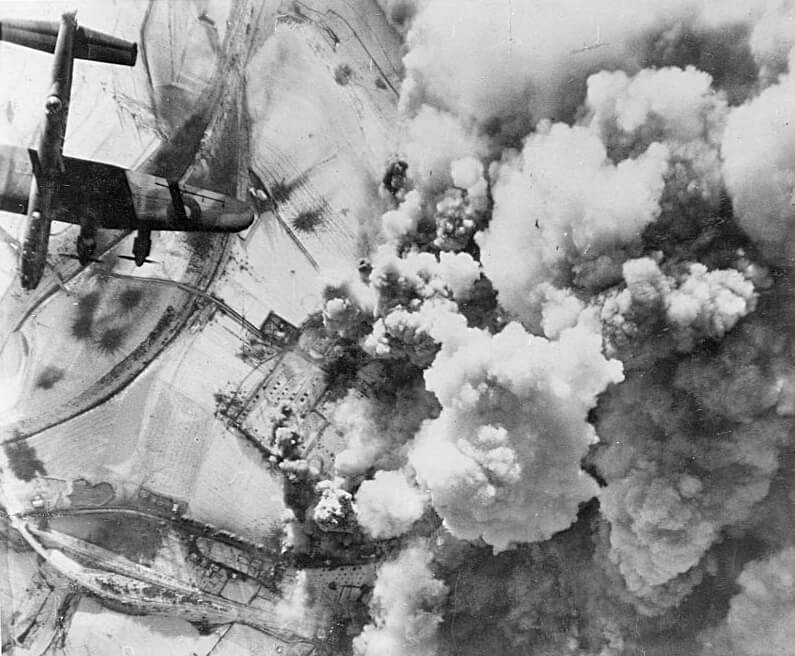

It was too late. The Americans dropped 500 tonnes of bombs on the complex. Despite warning leaflets, some 250 men, women and children sheltering inside were killed. The abbey was reduced to rubble in what Britain’s Guardian newspaper called “probably the greatest single aesthetic disaster of the war.”

“I don’t think the bombing was necessary or could be justified.”

Witnesses claimed German troops were seen running from the abbey as the first planes dropped their loads. Ten years after the war, the German corps commander in the Cassino sector, General Frido von Senger und Etterlin, still maintained that none of his troops were inside before the bombardment. He confirmed his U.S. counterpart’s conclusion that there were better observation sites elsewhere on the mountain.

The 79-year-old abbot himself and a civilian who had been in the abbey during the bombardment and who came into the American lines the next day confirmed that the Germans had never had weapons inside and had never used it as an observation post. Numerous emplacements, the civilian said, were less than 200 metres from the outside wall, and one position was about 40 metres away.

Field Marshal Lord Carver, former chief of general staff who wrote the Imperial War Museums’ official history War in Italy, 1943-45, had not heard of the intercept before Rupert’s book was published, but he didn’t think it would have influenced the decision to bomb.

British troops make their way through the ruins of Cassino.

[IWM/NS14999]

Regardless, the ruins created a superb German defensive position that cost thousands of Allied soldiers’ lives before the monastery fell after a further three months of fighting.

American newspapers published the falsehood that the monastery was inhabited by German troops, capitalizing on the headline that the Nazis violated the religious institution to use it as a safe haven.

In Germany, Monte Cassino became fodder for the propaganda machine to smear the United States as enemies of ancient religious traditions.

“This is the lesson we must learn: war—whatever its reasons and the historical motivations behind it—is always and will always remain a mistake.”

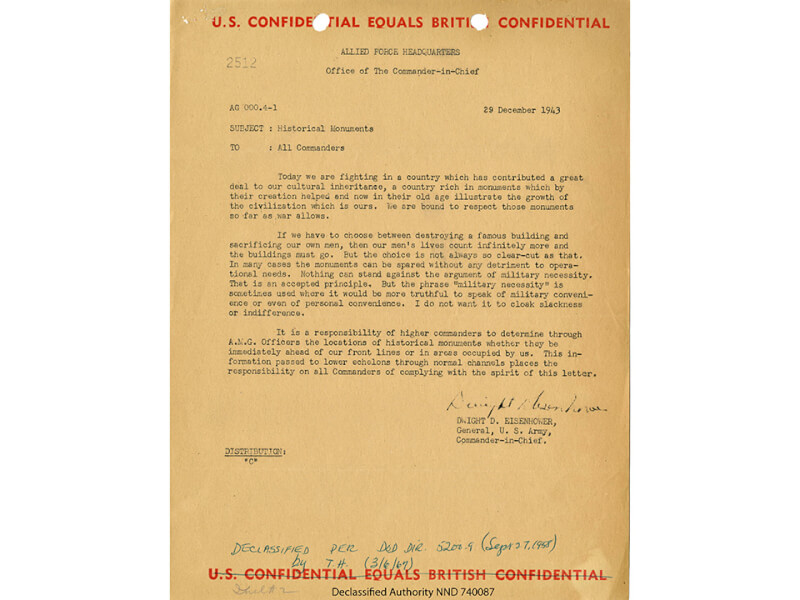

The abbey bombing came two months after the supreme Allied commander in Europe, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, issued his December 1943 Protection of Cultural Property Order.

“If we have to choose between destroying a famous building and sacrificing our own men, then our men’s lives count infinitely more and the buildings must go,” he wrote. “But the choice is not always so clear-cut as that.

“Nothing can stand against the argument of military necessity. That is an accepted principle. But the phrase ‘military necessity’ is sometimes used where it would be more truthful to speak of military convenience or even personal convenience.

“I do not want it to cloak slackness or indifference.”

On March 15, 1944, twice as many American planes bombed the town of Cassino itself, destroying nearly all of its homes and other buildings; 2,026 of the town’s prewar population of 20,000 were killed.

Monte Cassino was restored in the 1950s.

Eisenhower issued his Protection of Cultural Property Order in December 1943, to months before Monte Cassino was bombed. [U.S. National Archives]

In Belgium, Allied bombing in September 1944 killed 9,750 civilians and injured 40,000. The Allied policy was condemned by many of the country’s leading figures.

Roman Catholic Cardinal van Roey appealed to Allied commanders to “spare the private possessions of the citizens, as otherwise the civilized world will one day call to account those responsible for the terrible treatment dealt out to an innocent and loyal country.”

Officially, nearly 800 people (mainly civilians) were killed by mistargeted or wayward bombs in Nijmegen.

The lore is rife with images and accounts of victorious Canadian liberators parading along Dutch streets, swarmed by grateful women and children. There is nary a mention of the 10,000 Dutch civilians who fell victim to Allied bombs and at least 8,500 others killed by crashing planes shot down in the air battles overhead.

The Amsterdam-based NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies lists 40 British and American bombings in the Netherlands that killed between 40 and 800 civilians each.

The bulk were targeted attacks, some were so-called collateral damage, a handful mistaken bombings in which aircrews thought they were over Germany or they hit the wrong target, as in the accidental Royal Air Force bombing of a school in Copenhagen in which 123 civilians were killed, including 86 children. The intended target, the local Gestapo headquarters, was destroyed but part of the raid was misdirected.

In his 2004 paper “Restrained Policy and Careless Execution: Allied Strategic Bombing on The Netherlands in the Second World War,” Netherlands army Major Joris A.C. van Esch says bombardments in occupied countries haven’t received much academic attention in the Anglo-American discourse.

Nor, he adds, did Dutch postwar historiography often “know how to cope with these bombardments and their collateral damage.”

“As an illustration,” he wrote, “the official Dutch history devotes about twenty pages to the German bombardment on Rotterdam in May 1940, and only a few to the American bombardment of Nijmegen in February 1944, although they caused a similar number of casualties.”

RAF Lancasters attack the Belgian town of St. Vith in the Ardennes in 1944. Allied bombing in September 1944 killed 9,750 Belgians and injured 40,000.

[ RAF/Wikimedia]

Officially, nearly 800 people (mainly civilians) were killed by mistargeted or wayward bombs in Nijmegen. But historians believe many more who were in hiding at the time likely died. Much of the historic city centre was destroyed, including cathedrals and the intended target, the Nijmegen railway station.

The Dutch government-in-exile in London avoided criticizing countries it relied on for liberation and security, even after it was repatriated in 1945. Authorities at all levels largely remained silent on the bombing for decades, leaving survivors with unaddressed grief and questions, and allowing conspiracy theories to thrive.

Residents pick their wat through the rubble of Nijmegen, Nethlerlands, after Allied bombers laid waste to the town.

[Wikimedia]

Questions still linger in some quarters over whether some missions were justified, or if the crews were too tired or cavalier in their jobs.

“The political risks were readily understood,” wrote Dodd and Knapp. “These [ie. German-run factories and other French-built infrastructure] were not self-evidently military targets and some civilian casualties were inevitable.

“Attacks were planned with corresponding circumspection.”

During the invasion’s planning stages in March 1944, advisers warned British Prime Minister Winston Churchill to expect Allied bombing in France to inflict “between 80,000 and 160,000 [civilian] casualties…of which a quarter would be killed.”

Dodd and Knapp say the first acknowledgement of the sufferings of the French came from what might appear an unlikely source.

Residents watch a bulldozer clear the ruins of destroyed houses in Caen, on 10 July 1944.

[Conseil Régional de Basse-Normandie/LAC]

The fund raised 12,765 pounds (worth more than C$1.2 million today) in barely a month. Impressive, but less than the cost of a single Lancaster.

French President Emmanuel Macron has said now is the appropriate time to “balance” the remembrances of liberation by allowing people to express their memories of grief.

Macron paid homage to civilian victims during D-Day’s 80th anniversary commemorations in Marguerite Lecarpentier’s Saint-Lô, recalling how the town became emblematic of losses from Allied bombing after 352 of its 12,000 residents were killed and only two streets were left undamaged two days into the invasion.

Macron called Saint-Lô “a necessary target” and described it as “a martyred town sacrificed to liberate France.”

“Eighty years later, the nation must recognize with clarity and strength the civilian victims of Allied bombings, in Normandy and elsewhere on our soil,” he said. “We must bring this memory into full light.

“Without concealing anything, but without confusing anything. Because the inhabitants of Saint-Lô never mixed hatred or resentment with their sorrow.”

Michel Finck, 87, wept as he listened to Macron’s speech.

“Our house was destroyed,” he told Reuters. “Families in our street were decimated. The family transport business was also destroyed.”

They walked more than 80 kilometres to Cherbourg. At one point, German soldiers helped them cross a bridge.

Said Finck: “There were planes, bombs…this is not something you forget easily.”

Advertisement